When I was researching the slave trader Rees Porter, I came across a mention of him in the Freedmen's Bureau’s papers. I assumed, since this was the Freedmen's Bureau, that this would be in relation to a Black person, but I guess my understanding of what all the bureau was doing after the Civil War is incomplete, because this does not seem to have involved Black people at all.

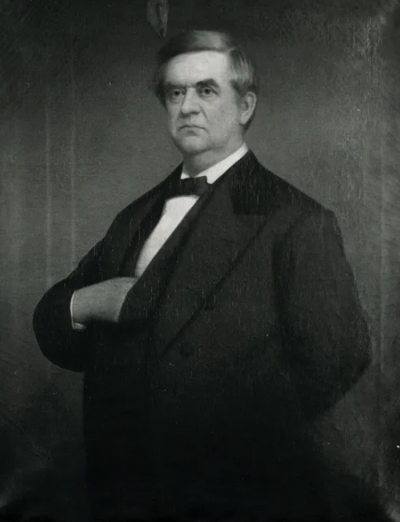

Porter came up as someone who could verify that Thompson Anderson was loyal to the Union and had not abandoned his downtown house. I found this curious, so down the rabbit hole of history I went. Anderson was a merchant. According to his obituary in the May 16, 1895, issue of the Nashville Banner, Anderson was born over in Wilson County and lived in Lebanon until 1844. Then he lived in Clarksville for a decade before coming to Nashville to own a series of wholesale dry-goods businesses. He was a Methodist and a Mason. He was one of the founders of Mt. Olivet Cemetery, and his first wife is thought to be the first burial in said cemetery. His obituary is strangely silent about how he spent the war. We go straight from “This firm continued in successful operation until the outbreak of the Civil War,” to “At the close of the war the firm of French, Anderson & Co., dealers in agricultural implements, was organized.”

So what was going on with Anderson during the war? Well, he and his friends spent some time explaining it to the Freedmen's Bureau. One Mr. Shackelford (looks like his initials could be J. D. or D. O.) wrote directly to General Clinton Fisk (yes, Fisk is named for him) about Anderson’s plight, such as it was. Judging by the smears and blobs on the page, Shackelford may have been lefthanded and thus his crappy penmanship is forgiven, though it does make deciphering what he was telling General Fisk difficult. This seems to be the relevant part: “Mr. A informed me his house had been seized when he was [this word looked like “arllered” but I think, from context, it must be “ordered”] south and is [no idea. Looks like ‘zel hitdi’], in the commencement of his out breach Mr. A was a strong union man voted against insurrection.”

Whew. You know, as a side note, old people bitch about, “Oh, no one knows cursive anymore. They don’t teach cursive. How will kids today know how to read old documents?” I grew up being taught cursive in school and Shackelford’s letter is nigh on indecipherable to me. I’m even starting to have doubts that I’m reading his last name right. So, let’s hear it for typing!

Luckily, next, we hear from Anderson himself, and whoever wrote his letter has beautiful handwriting. The reason I suspect Anderson was dictating his letter to someone is that it starts “Sir: the undersigned desires to submit the following statement,” which would suggest the involvement of a third party recording said statement. Anyway, now we get the skinny in Anderson’s own words:

In the Spring of the year 1863, I was arrested by order of the military authorities and confined in the military prison—without any charge of a specific offense—but upon the general one (if any) of being a disloyal person. I was notified that as such I should be sent south of the lines of national military occupation, to remain during the war. As soon thereafter as I could, I prepared a paper, which I sent to Maj. Gen. Rosencrans, com’d’g [sic] the department, protesting against the charge of disloyalty—setting forth that I had been at all times a loyal citizen of the United States—that I had voted against secession or separation—and been against it at all times—that I still was against the (so-called) Southern Confederacy and for the old Union—that I have never given aid or comfort, voluntarily, to the cause of the rebellion, nor indeed in any important way (if at all) involuntarily.

This all seems reasonable and plausible. But then Anderson spends the bulk of the letter complaining about being forced to take the oath of allegiance. “I was willing to join with my loyal fellow citizens, or the citizens in general, in taking the oath of allegiance, but I wished to be able in good conscience to swear ‘that I take this obligation voluntarily.’ I would not and did not consent & could not consent, to take an oath under the duress of imprisonment and sear that it was done ‘freely and voluntarily.’”

Y’all, I love Thompson Anderson so much and it pains me. He was into secret societies. He started a cemetery. And here he is being a pain in the ass to government officials over the most pedantic shit. If someone raised him on a Ouija board, he could come write for the Scene. Put a curly-haired wig on him and he could write this.

And bless him, we know from Shackelford’s letter what the purpose of this letter is supposed to be: “I’m a loyal Union man. I never was anything but a loyal Union man. I didn’t willingly abandon my house. Please give it back to me.” But this corny motherfucker spends a full page-and-a-half arguing about how he shouldn’t have to take the oath of allegiance because he never was disloyal, and anyway, how can he freely and voluntarily agree to something if not agreeing to it means going to prison? And, by the way, the Rebel Gen. Wayne can certify that Anderson “rendered no voluntary service against the Government.” This highly suggests that before being a pedantic ass to Fisk, Anderson spent some time during the war being a pedantic ass to Wayne.

It's, as the kids say, so cringe, and yet the cringe in my case is because I recognize it in myself.

Finally, FINALLY — or in the style of Anderson, finally — in the last paragraph, he gets around to asking for his house back. “I did not therefore ‘abandon’ said property. It was however, after a while, taken for military purposes, and has been so used in the past, but in part, as I have been informed and believe, it has been used under a quasi military protection, by a Miss Loofmoumow [sic], not connected with the service, as a boarding house.”

Listen, if at any time during the Civil War you come across a woman under quasi military protection running a boarding house in Nashville, your eyebrows should rise up so high they almost leave your forehead. Who Anderson is talking about is actually Mary L. Loofborrow. She was renting from the government a “brick dwelling house — situated on the North side of Church Street near Chattanooga Dept. in the City of Nashville State of Tennessee. Excepting the two (2) Front Rooms on right hand side of building on first and second floor.” She paid $60 a month. Was she running a brothel out of Anderson’s house? It's hard to say with so little information. But Anderson did complain that his house was “much abused.”

Anderson did get his house back in October 1865. He and his family lived at 199 Church St., which would have put him just down the street from the Masonic Hall, McKendree Methodist Church and, oddly enough, Mary Loofborrow, who lived at 188 Church St. That must have made for some awkward encounters between neighbors.

Anyway, there’s lots here I didn’t know: that the Freedmen's Bureau also had to deal with white people who wanted their property back; that Confederate sympathizers (or suspected ones) were sent out of Nashville during the war; and that Mary Shelby Anderson was the first burial at Mt. Olivet. So this ended up being a fruitful rabbit hole.