A small coup at the Board of Zoning Appeals this month sets Metro up to litigate against itself in the next 60 days.

Members of the board overturned zoning administrator Joey Hargis not because they determined he had erroneously applied a law — the Metro Code of Ordinances tasks the board with checking and balancing — but because they took issue with the outcome.

The ruling in question focused on Battlefield Estates, an affluent enclave off Woodmont where most houses are set back 80 feet from the road. Neighbors on Sutton Hill Road brought the appeal, which allowed builders to proceed with a 60-foot setback, deviating from the street’s “contextual line.” By the letter of the code, the builders are allowed 60 feet. No one, including the board, contested Hargis’ reading of Metro’s setback ordinance. Instead, the question became whether this indisputably correct application of the law aesthetically protected the neighborhood.

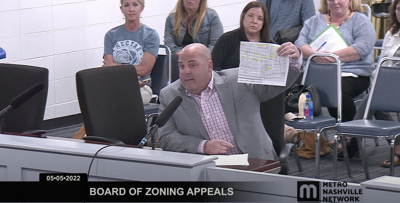

Hargis, who just completed his first year as zoning administrator, maintained that his role was to correctly apply existing ordinances. “If this board grants this appeal, you are creating chaos in my office,” Hargis told the BZA. “They’re asking this board to act as a legislative body, to change the law. And that’s not this board’s power.”

Former zoning administrator Jon Michael tapped in to reiterate that point. Michael emphasized that the law is clear, straightforward and correctly applied, even if it leads to undesirable outcomes for neighbors.

“No opinion with regard to aesthetics has a place in this conversation,” Michael told the board.

Anna Teeples, an interior and exterior home designer who lives two blocks away from the proposed build, articulated her fears of how a different setback would threaten the neighborhood. “We’re a front-yard neighborhood," Teeples told the board. "We have block parties together. We trick-or-treat together. All of a sudden, we become the tear-down neighborhood, and I don't like that. That’s because we’re losing this battle of the setbacks.”

Board member Tom Lawless led the opposition on behalf of the neighborhood. Lawless, a commercial litigator, argued that the board must ignore current law to deliver an equitable outcome. “We all want to be in a nice neighborhood at some point in time or some place that we’re comfortable,” Lawless told his colleagues. “In this instance — and I'm a property-right type of person — I just can’t do it this one time.”

Lawless invoked the landmark school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education to make the point that moral charges sometimes command bodies to overturn legal strictures. “There was law at one point in time that said I couldn’t go to school with Joe or Ashonti,” said Lawless, referring to Joseph Cole and Ashonti Davis, two Black members of the Board. “That was wrong. And until someone stood up and said no, it couldn't be changed.”

Board member Christina Karpynec prodded the existential meaning of the BZA, posing this question to colleagues: “What’s the point of having the BZA? If we had to follow the strict application of the law, why bother having the BZA? We are allowed to look at the gray.”

The drama played out over 45 minutes with Karpynec, Lawless and fellow board member Logan Newton joining to enforce a contextual 80-foot setback and overturn Hargis. Locked at 3-3, the case stayed on the BZA docket until May 19, when newcomer Payton Bradford broke the tie.

An hour after members’ impassioned debate about curbing property rights to deliver equitable outcomes for neighbors, two Black residents contested the circumstances of a new build on their North Nashville street. Developers had increased density on their street, historically single-family homes and churches, bringing in Airbnbs and fitting multiple homes on a single lot. These developers wanted to throw out a required landscape buffer so they could more easily put two units on a 20-foot-wide sliver of grass.

“I wouldn’t build it, personally,” said Karpynec about the proposed units in North Nashville. “That’s just my personal opinion, that’s not even relevant really. If they can build it, they can build it. It seems like they’re allowed to build it.” Members approved the variance in favor of developers.

The board’s willingness to determine appeals on equity, selectively or at all, seemingly breaks its legal mandate and creates internal contradictions at Metro that set up complex legal proceedings.

From here, the contested setback will likely go to Chancery Court. Metro can sue (and has sued) itself, and this ruling pits the BZA’s legal authority against a clearly defined Metro ordinance. It’s not clear who will represent which party as both are technically under Metro’s legal department. The May 19 ruling sets up a 60-day window for Metro to file legal proceedings.