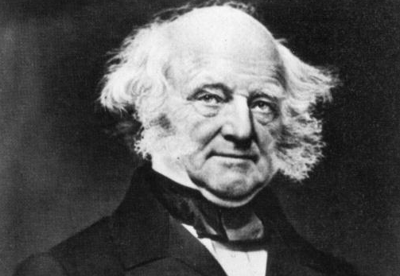

Let’s be honest. Martin Van Buren is mostly known for being mostly unknown. Here are the things I know about Martin Van Buren: His name was Martin Van Buren, and he was president of the United States. One of those facts is technically wrong, as his name originally was Maarten van Buren. Van Buren, the eighth president, was the first president born in the United States (as opposed to the pre-U.S. colonies). Funnily enough, he was our only president whose first language wasn’t English.

Van Buren in life was mostly an East Coast kind of guy, but in death, he’s become a Tennessean. Well, not Van Buren, exactly, but Cumberland University, over in Lebanon, which has become the home of the Papers of Martin Van Buren. The project is really cool. The people involved are digitizing all of Van Buren’s papers to make them available for free on the internet. They’ve got a large collection of Van Buren’s papers on microfilm, which contains all the items held by the Library of Congress, but they’ve also got items from people’s personal collections.

You can see why this would be a boon for history buffs — it’s a huge trove of primary sources that will be available for free. And you can see why this will be a boon for Van Buren’s legacy, since it should increase his name recognition, if only because his papers will come up when people are researching Andrew Jackson’s legacy.

But I think this is also a really good thing for Tennessee. We already pride ourselves on being the fertile ground from which the Democratic Party sprang, and Van Buren was crucial for solidifying the party and making sure it functioned. (Come back to us, Martin Van Buren!) Bringing this project into Tennessee in many ways makes the state a one-stop shop for all your Early History of the Democratic Party needs and an important stop for your Jacksonian America needs.

I asked Mark Cheathem, professor of history at Cumberland and co-editor of the project some questions about Van Buren and the papers. (Disclosure: in the other parts of our lives, Cheathem co-edits a book series that I market).

The Papers of Martin Van Buren project has been around for a long time, but it seems to have been dormant for quite a while before you decided to revitalize it. I'm curious about how you realized there was this project that could benefit from scholars taking another look at it, and applying new technologies to it, and what made you realize you could be the one to do it.

The credit goes to James Bradley, a New York journalist and historian. In 2013, James interviewed me about my book, Andrew Jackson, Southerner, for his now-defunct blog, American Talleyrand. When I gave a talk about the book in New York City the following summer, we met in a cafe, and he pitched the idea of reviving the Papers of Martin Van Buren in digital form. I took the idea back to Cumberland’s administration, and they have supported the project 100 percent. Their support has been so strong, in fact, that other presidential papers directors have commented that their university administrators could learn some lessons from Cumberland’s example.

There is definitely a shortage of Van Buren scholars today compared to three decades ago. Thankfully, I am in a good position, with my own scholarship on the Jacksonian era and my university’s support, to take on this kind of project.

The technological piece that you allude to is fascinating to think about. The papers were originally at Penn State University from 1969 to 1987. They were microfilmed as part of that project, because microfilm technology was considered cutting-edge. But how many people own, or have easy access to, a microfilm machine? Not that many, and certainly not as many as have access to a computer or smartphone. By placing these transcribed documents online for free, anyone with an Internet connection can read them and, hopefully, they can see how important Van Buren was to our nation’s political development.

The Papers of Martin Van Buren website has one of the shortest, most informative, and delightful FAQs I've ever read. Who wrote that? And on a related note, which nickname do you think is the sicker burn? Martin Van Ruin or the Little Magician?

I wrote it! As a new project, we have not had many questions. But I needed something to fill that space on our website, so I tried to think of questions that would pique someone’s curiosity.

As far as nicknames, Martin Van Ruin is worse; at least “the Little Magician” suggests some cleverness. There’s actually a folk-rock band named Martin Van Ruin, by the way.

Forgive my sexist metaphor, but, if Andrew Jackson is the Father of the Democratic Party, Van Buren could be said to be its mother — the one who figuratively put on the party's shoes and tied them and made sure that it ate dinner and would grow up to be big and strong. I know we in Tennessee tend to talk about the early Democratic Party as being a Tennessee accomplishment. Could you talk a little about what Van Buren did for the party in those early days?

Van Buren’s Whig opponents, who called him “Aunt Matty,” would have loved your comparison!

Van Buren was the architect of the Jacksonian Democratic Party, and without him, Jackson doesn’t win the presidential election of 1828. Van Buren pulled together the national coalition — John C. Calhoun in South Carolina, William H. Crawford in Georgia, Thomas Ritchie in Virginia, and his own supporters in New York — that Old Hickory needed to become president.

In an unexpected way, Van Buren was also responsible for James K. Polk’s election in 1844. Van Buren seemed to be the prohibitive favorite going into the Democratic national convention, but he made a fatal mistake shortly before the delegates met in Baltimore: He came out publicly against the annexation of Texas. Tennessee delegates were part of a faction that kept Van Buren from winning the nomination; when it was clear that he wouldn’t win, Democrats rallied behind Polk as the party’s nominee.

Van Buren also used his political experiences in New York to reintroduce the two-party political system that for better or worse, we still have today. Unlike George Washington, Van Buren saw partisanship as a positive characteristic that would tamp down the growing sectional discord that threatened to turn into an inferno. In some sense, he was successful for several decades, but even he could not have predicted how sectionalism would overwhelm the nation in the 1860s.

I'm also curious about Van Buren's anti-slavery stance. The older he got, the more straight-up abolitionist he became. And yet the Democratic Party in those early years was full of slaveholders, including Jackson and Polk. How did that work? Were Van Buren's stances just ignored by the party? What did the slave-holders make of him?

One of the lyrics in the They Might Be Giants’ song, “James K. Polk,” calls Van Buren an abolitionist, but in reality, he was pragmatic about the slavery issue. He wanted the two-party system reinvigorated to help mask the divisions over slavery, but when he ran for the presidency in 1836, he found himself forced to defend slavery in order to shore up his Southern base. The same thing happened in his re-election bid in 1840 — Van Buren chose to support slavery in order to retain Southern voters.

Van Buren’s last foray into presidential politics in 1848 was as the candidate of the Free-Soil Party, but there are three things to keep in mind about his nomination. First, while the Free-Soil Party had abolitionist factions within it, it was primarily a party interested in protecting white ownership of land in the Western territories, not in helping enslaved African-Americans. Second, Van Buren accepted the nomination reluctantly, and it seems he did so mostly to help his son, John, advance in New York politics. Lastly, Van Buren was not happy about losing the Democratic nomination to Polk in 1844, so there was an element of revenge in joining a third-party movement that would hurt the Democrats more than their Whig opponents. Most scholars believe that the Free-Soil vote in Van Buren’s home state of New York ultimately swung the election against Democrat Lewis Cass to the Whig candidate, Zachary Taylor.

Is there anything you've learned about Van Buren from being so deeply involved in preserving his papers that you've found surprising or particularly neat?

We are still in the early stages of the project, but we’ve already transcribed some interesting documents. One is an 1826 letter in which Van Buren describes a duel between Secretary of State Henry Clay and U.S. Sen. John Randolph. (And we think today’s politics is divisive!) He also describes his vision of what became the two-party political system in an 1827 letter to Richmond, Va., newspaper editor Thomas Ritchie.

Students working on transcribing the documents leading up to the 1844 Democratic National Convention have commented on how clueless Van Buren and his supporters were in understanding his tenuous position within the party. That comment is one of the cool things about the project. Working on the documents allows students to see the contingency of history as it unfolded, not just the perspective of hindsight that living in the 21st century provides.

I know you're hoping for state funding of the project. What would that money allow you to do?

Many people do not realize how difficult it is to fund these projects. The Jefferson Papers, which are at Princeton University, has six full-time editors, while the Washington Papers, at the University of Virginia, has 12 full-time editors. Both of these universities are large elite institutions, with lots of money.

Our pockets are not as deep as these universities. Many people do not realize that Cumberland University is, by far, the smallest university to host a presidential papers project. I am the project’s only editor, and I am only part-time, spending half of my time fulfilling the usual duties of a professor — teaching, advising, attending committee meetings, etc. At our project’s current rate of production, I will be long retired before it is completed, and I am a relatively young man!

The amendment to the higher education funding bill that is currently before the General Assembly would provide us with money to hire several full-time editors. This is a crucial step that we need to take in order to advance the project. If we can make substantial progress with these funds, I think we will have more success in securing private grants and donations.