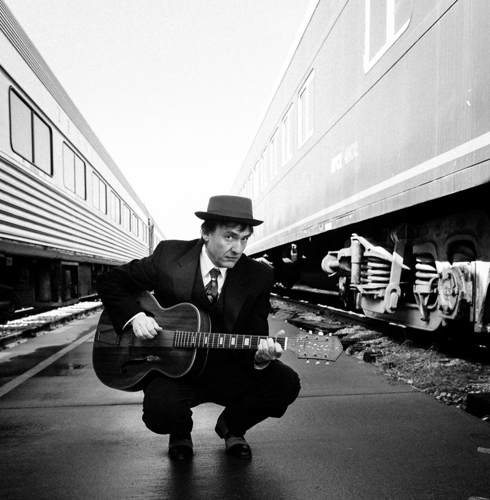

Paul Burch at Tennessee Central Railway Museum.

Ask Paul Burch where the inspiration for his stunning new album Meridian Rising comes from, and the answer goes back almost 20 years. Longer than that, actually. As the story goes, in November 1927 Ralph Peer got a call out of the clear blue sky at the offices of the Victor Talking Machine Co. in Camden, N.J. Three months earlier, he'd been scouting talent in Bristol, Tenn., the metropolitan hub of the Appalachian Tri-State area. He set up a makeshift studio on the third floor of the Taylor-Christian Hat and Glove Co. on State Street, and there he recorded hillbilly singers, string bands, church choirs, anybody with promise who'd cut a single for $50.

Now here was one of them on his doorstep: a fella named Jimmie Rodgers.

At the session in August, Rodgers turned up as a solo act after a dispute with his backing group. He said it was over billing, though at least one band member would later say it was because he hocked their instruments without consulting them. Victor put out a single from the session in October 1927 — "The Soldier's Sweetheart" backed with "Sleep, Baby, Sleep" — but though promising, it didn't light their world on fire.

It did Rodgers'. The youngest son of a foreman on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, he'd grown up exposed to all kinds of vaudeville and show music in his schoolteacher aunt's care while his dad was making his rounds. His native Meridian, Miss., had all the cultural wonders of an early-century railroad hub, from baseball to circus folk to traveling singers and artists of all kinds. He'd been hauled back home twice by age 13 for sneaking off to mount his own tent shows.

He'd grown up in Meridian watching larger-than-life figures whisk through town by rail. When he joined the family trade — first as his dad's waterboy, then as a brakeman on the New Orleans and Northeastern — he started to become one of them. He learned, and loved, black music. He picked up guitar from hobo pickers, developing a simple but forceful strum that set off his increasingly nuanced vocals.

After the railroad laid him off, a family man twice married before the age of 25, he gigged through the mid-1920s in traveling shows as he sought to make his play. He didn't want to be the brakeman on the gravy train. He wanted to ride it — to own it.

That train had rolled into the station in Bristol. Victor just didn't know it yet. While the label (later RCA Victor) turned its attention to other artists from the sessions, such as The Carter Family, Rodgers was getting impatient at home in Washington, D.C. Maybe other people had time to burn, but not him. He'd been diagnosed with tuberculosis, a short track with only one stop.

Armed with business cards that identified him as a recording artist, he set out impulsively to force the label's hand. He drove to New York, set up at what became the Taft Hotel — sending the bill to Victor — and called Peer. How about a session? he asked.

Peer liked his entrepreneurial nerve. After all, he was seeking folks who had their own material, the better for his publishing and ownership stakes. They didn't know it, but the father of the recording industry was about to shake hands with the father of country music.

That's because the song they cut in Camden, "Blue Yodel No. 1 ("T" for Texas)," would become one of the most influential recordings ever made. It sold more than a half-million copies in 1928 and made its singer a hall-filling superstar. He would go to Hollywood to discuss making movies, be wined and dined with Laurel and Hardy, barnstorm the country on a Depression relief tour with the other great populist entertainer of the day, Will Rogers, and write and record standards that are part of a Lower Broadway house band's repertoire even today. He would indulge every musical whim he had, whether it was recording blues duets or jazz with Louis Armstrong and his wife Lil Hardin. In the process, he would woo women, skirt trouble and gamble away fortunes, just to show that the kid from Meridian had the money to lose.

And in the end, just five years later, he would rise from a cot in the Taft Hotel and end his recording career just as he started it: a man and a guitar, summoning breath from his clotted lungs to finish a song called "Years Ago." Thirty-six hours later, he would be dead.

But he left us "Blue Yodel." In its fusion of blues and folk, in its lusty singing and chugging rhythm, you don't just hear the origins of modern country music, though everyone from Merle Haggard to Lynyrd Skynyrd to Tompall Glaser on Wanted! The Outlaws would cut it. You don't just hear Johnny Cash, who's unthinkable without Rodgers' influence. You hear Woody Guthrie, and Bob Dylan, and those who came after, along all the spider-webbed tributaries that make up roots music.

Jimmie Rodgers would still be dead at a young age if he hadn't made that impulsive trip to New York. But we wouldn't have "Blue Yodel," and the music of a century. We also wouldn't have Meridian Rising, coming out this Friday, a feat of empathy and imagination that asks us to view the world in the brief but blazing light of the Singing Brakeman's lamp.

It opens with a curtain-raising wail of clarinet — a flourish you'd expect more from a klezmer record, or Gershwin. Then a simple acoustic-guitar figure, and a setting of place: "Let me tell you all about the place I'm from / Where the police tip their hats while they're swinging their clubs."

The singer is Jimmie Rodgers, recalling a time when he was not yet the showman who would turn Ralph Peer's head, but not long for his hometown of Meridian either. He describes a parade of purest Americana: creep joints, barrooms and pool halls, fine ladies with parasols. Through this amber-tinted sonic tableau, Chloe Feoranzo's clarinet wafts like the scent of jasmine, while Tommy Perkinson's drums snap and rattle a lazy shuffle.

Though Rodgers watches this procession, he doesn't feel welcome to join it. When blue bloods see him coming, they shut their doors. No matter. The next time they see him, he'll torch the town like Sherman. He's seen something bigger. He caught a peek through the back-alley door of the local opera house to see a black vocal group, he says, "and I wanted no part of my town anymore." Waved farewell by the music's Dixieland lilt, sweet and breezy, he hops a Pullman with the lead singer down to New Orleans, "laughing how them cultured sons-a-bitches sure is mean."

The striking thing about "Meridian" as the opening song of an imagined musical autobiography of Jimmie Rodgers is that it doesn't sound like Jimmie Rodgers. It isn't blues, it isn't country; it isn't exactly a train song, though it forms a veritable switchyard of real and imaginary railroads. And where's Rodgers' signature, the blue yodel — the otherworldly sound that famously convinced the Kenyan Kipsigis tribe in the 1950s that he must have been a half-man/half-antelope creature known as "Chemirocha?"

"I'm not much of a yodeler," Burch confesses, laughing in his home in a leafy Nashville neighborhood.

What it evokes instead is an atmosphere. In "Meridian" you don't hear a slavish attempt to narrate Rodgers' life. It's not some kind of cornball singing Wikipedia entry — "Oh, my name is Jimmie Rodgers and I come from Mississip' ..." You hear the world he wandered, a mythic early 20th century America of hard times, traps and lures that is dimly remembered but firmly anchored in the imagination.

The music, meanwhile, is full of snatches of sounds Rodgers would have carried in his head without imitating any one style or song: marching-band snare, cathouse piano, a gently huffing tuba. The 19 songs that follow on Meridian Rising take a similar approach to Rodgers' life. They're studded with names and details, but while many are real, others are invented or repurposed — all used to render Rodgers' world and times in living color rather than sepia.

"This is a different Jimmie Rodgers," says Peter Guralnick, the veteran music journalist and scholar noted for his magisterial biographies of Elvis Presley, Sam Cooke and Sam Phillips, who met Burch in 1998 on a visit to the Southern Festival of Books and struck up a friendship. "This is an imagined Jimmie Rogers, kind of like Elvis Costello's Jimmie Rodgers imitator in 'Jimmie Standing in the Rain.' But it's the same Paul I've always known, bright-eyed, imaginative, exploratory, always willing to try on a new melody, a new avenue of exploration, a new suit of clothes. This album can take its place in an explosion of independent Nashville-based albums released recently, including Colin Linden's Rich in Love and Kevin Gordon's Long Gone Time, demonstrating the ongoing creative ferment that continues to exist right here, right now, just beneath the surface."

The album charts Rodgers' path from his early ambitions — registered in the slinky rocker "Cadillacin' " as his love of fast cars and his growing distance from the common folks who envy them — to his lowest ebb pre-fame: the death of his second daughter while he was struggling on the road. Burch portrays the despondent singer, newly diagnosed with the TB that killed his mother, staring into the swirling Mississippi. "Ain't That Water Lucky," he wonders, in one of Meridian Rising's most haunting songs. Maybe he should just go under.

Then comes the "Blue Yodel" windfall. Flush with cash, he moves to Texas but sets up a headquarters for hardcore honky-tonkin' at San Antonio's Gunter Hotel, site of Robert Johnson's early recordings as well as (print the legend) the ghost of the blonde hacked to pieces in Room 636. Burch's hard-swinging "Gunter Hotel Blues" captures the high life as a revolving door of wild characters like Leapin' Lena, found dead by a hotel detective but not before (thanks!) she's paid the singer's bill.

But the hellhound that would dog Johnson's trail is already closing in on Rodgers. In a sober, unclassifiable duet called "If I Could Only Catch My Breath," the ailing singer tries to wheedle a booking from an overseas promoter, played in a musical cameo on separate versions by Billy Bragg and Burch's frequent collaborator Jon Langford from the Mekons and Waco Brothers. The booker tries gently not to say the obvious: You're dying. After one last letter home from the Taft Hotel ("Sorry I Can't Stay") the singer summons his strength for a final pledge to go "Back to the Honky-Tonks." That showbiz obligation is trumped only by death, and a rollicking Dixieland burst sends both the album and Jimmie off, as perversely jolly as Roy Scheider's literal big finish in All That Jazz.

A concept album about a singer who slowly died of tuberculosis at age 35 perhaps sounds like a drag (though don't tell Haggard and Dylan, who put together excellent tribute records to him). That goes double for an "imagined musical autobiography," which threatens to layer a half-inch of well-intentioned dust on the proceedings. That's not Meridian Rising, a record whose open spaces leave room for swinging grooves, outrageous murder ballads, hot jazz, gutbucket country, dad jokes ("Room service? You'd better send up another room"), and an almanac's worth of odd and attention-grabbing stray details. In that sense it has some of the yellowed small-town newspaper feel of The Basement Tapes, and it too rocks without sounding fussed over.

"Typically, when you make a record, you're trying to make this idealized thing," Burch says, framed by the orderly disorder of his studio: a Kelly Williams painting, an American flag draped neatly behind his drum set. "I wanted to do the opposite of that. I feel like everyone's records, including mine — anyone who's been making records over the last 50 years — has been trying to make this very nice package. I wanted to test myself. I just wanted to kind of blow up, or explode, the framework that I'd been in. The only way to move forward is appreciate what you've done, and rebuild it. This record became everything I wanted it to be."

Most impressive, though, is that at a time when music-making gravitates toward singles and scannable units — units as easy to skip as choose — Burch has made an album that demands, and rewards, to be listened to as an entire work. Listen to Meridian Rising in pieces, and it's by turns rowdy, funny, exquisite and sad. Spend some time with it, and it stirs your imagination — not just about Rodgers' life and music, but about the world and time beyond.

That's something of the effect the project had on Burch, who lives with his wife, Cherry Street Eatery & Sweetery chef-owner Meg Giuffrida, and his bright son Henry, who appears on the record (however reluctantly), in a quiet neighborhood with many musicians nearby. Soft-spoken but possessed of a voracious curiosity and a puckish sense of humor — and articulate and analytical about his own music as well as others' — Burch would seem to have little in common with a rail-riding, womanizing high-roller who gambled his numbered days. But he could sympathize with Rodgers' being able to trace his life-changing career path to an impulsive decision.

He remembers the night in 1994 he was new to Nashville, and a friend from back home in Indiana, Jay McDowell, wanted him to go downtown. After years of seedy decline on Lower Broad, the once-padlocked Ryman had reopened to acclaim, and a group of musicians who embraced the city's country music heritage were starting to bring hard-country fans back to Tootsie's and the block's honky-tonks.

McDowell, alas, caught a bug. What to do? Burch hemmed and hawed, but in the end, he didn't want to stay home. He arrived at Tootsie's as various musicians were rotating on and off stage with Chuck Mead and Shaw Wilson's act Dos Cojones. He ended up sitting in with the group on drums, joined by Greg Garing, when someone in the crowd hollered a dare: $25 for every Hank Williams song they could play. He had picked the wrong guys. By the time they finished, the guy had maxed out his ATM withdrawal.

When word got out who lost the dare — country star John Michael Montgomery — the story made headlines and instantly entered the annals of honky-tonk lore. It also gave an enormous boost to the district that had clubgoers flocking to Lower Broad in a way they hadn't in decades. In The Other Paris, social critic Luc Sante makes the point that art flourishes everywhere except in spaces that are designated for it. Had someone launched a project to revive the honky-tonks, there'd still be dust on the barstools. It took the musicians who began playing there — among them Burch and Garing, plus Mead, Wilson, McDowell and their bandmates in the mighty BR549 three doors down at Robert's — to raise the district's fortunes.

Burch went on to become a bandleader himself with his WPA Ballclub, and played in an early version of Lambchop. He recorded his own albums, attracting an overseas following as well as high-profile fans such as Mark Knopfler and the late British tastemaker John Peel. But the spark that led to Meridian Rising came from a review of his 1996 debut LP, Pan-American Flash. Writing in Entertainment Weekly, critic Meredith Ochs called Burch "a modern-day Jimmie Rodgers." More than the compliment, Burch recalls, he was struck by the juxtaposition of the phrases "modern-day" and "Jimmie Rodgers." What would such a thing sound like?

The idea simmered over the years, recalls Fats Kaplin, a WPA Ballclub heavy hitter for almost two decades and an in-demand multi-instrumentalist perhaps best known for his recent work in Jack White's band. Kaplin is Burch's reliable resource for anything involving the distant past, especially music.

"That's the way Paul is," says Kaplin, who shares with Burch an affinity for antiquated grift, argot and vaudeville acts that finds a home in Meridian Rising songs such as "Girl I Sawed in Half" and the gambler's lament "Black Lady Blues." "He'll get interested in something, and it'll start popping up in what he does. Jack White's the same way." While he could tell Burch considered Rodgers a personal hero, Kaplin explains, it was less because of his music than his model.

"He came at it more from a literate, historical angle without being eggheaded about it," Kaplin says.

For Burch, the moment that clinched the project was finding a 1931 single by Rodgers called "Let Me Be Your Sidetrack," cut as a duo with African-American blues guitarist Clifford Gibson. What struck him about it was that it sounded absolutely free: beholden to no single genre, audience or style, not even to the beat itself, as the two musicians slow and quicken in simpatico. If Rodgers were around today, Burch says, he wouldn't have much in common with Americana acts and the pinpoint pigeonholing of roots music. He'd be David Bowie or Lady Gaga — musical shape-shifters emboldened to incorporate any style or change their look however they see fit.

"He just had the confidence like, 'This is interesting to me,' " Burch says, serving coffee in ceramic mugs with amusing ceremony in his studio, where just minutes before he'd been listening to Bowie's benedictory avant-jazz album Blackstar. "There were all these interviews that came out after Bowie passed away, and he said, 'I wanted to take all these things I liked and put them in my music.' I think he says that in his documentary Five Years. That's something Jimmie would say."

The ultimate irony, Burch says, is that the man sometimes called the Father of Country Music was an early collector of all kinds of records — save one.

"He did not like hillbilly records," Burch says. "He did not like old-time, scratchy fiddle music. No scratchy fiddle in Jimmie Rodgers' music. So when I say that he has more in common with someone like David Bowie than with anything really happening in Americana today ... [it's because] Jimmie didn't want to leave anybody behind. He didn't want to be that specific. And the way to do that is to have a really strong personality that can do a lot of different kinds of music. He played with the Mississippi Sheiks and Clifford Gibson and did a lot of different kinds of music."

Over the years, Burch began gathering details about Rodgers' life, aided by sources such as Nolan Porterfield's early biography. He contacted Nashville author Barry Mazor, whose acclaimed 2014 book Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Roots Music makes a case for Peer and Rodgers both as pioneers of the modern recording industry, and has done much to spur a revival of interest in Rodgers as well as Peer's Bristol Sessions. From Mazor he got the wonderful story about Rodgers losing his shirt in a card game with legendary gambler Mark Boasberg. The singer escaped only by writing an IOU on the spot for his losses to the Kerrville Texas Bank. Rodgers found it wise to go the long way around Louisiana once Boasberg learned there was no such bank.

But as much biographical information as he absorbed — "He did his homework," Guralnick says — he preferred to let his imagination supply what facts couldn't: mood, mystery, the intangibles of how it must have felt to live that life. A case in point is the tall tale "Girl I Sawed in Half," a yarn involving a two-timing circus gal, her strongman inamorata, some pickled wine, and a magic act that goes badly enough astray to require the legal services of Finishin, Flanagan & Ford, Esq., of New Orleans. True, the historical record does not show Jimmie Rodgers involved in any premeditated big-top bisections. But as a distilled dramatization of the carnivalesque world that surrounded Rodgers at various points in his career, it gets at a tawdry truth beyond timetables.

"Once I started writing, I stopped listening to his music, and the writing took over," Burch says. "Each tune was sort of like a short story in itself. I thought about this for about 15 years, and when I finally got down to doing it I made a list of songs that would cover all the things in his life I thought I should." He pulls out a notebook reinforced with packing tape, bulging with slips of paper bearing lists of phrases and possible song titles. "At one point I knew that I wanted to write about tuberculosis: I had the idea of writing a song called 'Iron Lung,' or 'Lunger.' "

In the end, the biggest influence on Meridian Rising may have been the WPA Ballclub itself. Its longest-serving member is Burch's co-producer and constant ally Dennis Crouch, the phenomenal bassist who's become a go-to player for the likes of T-Bone Burnett, Elvis Costello and Diana Krall (with whom he's currently touring Asia). When Crouch became available for a few days to record last year, writing the record went from a someday prospect to an urgent project with a looming deadline. The one thing they knew, Crouch says via email, was that they didn't want it to sound like a Jimmie Rodgers re-creation.

"It's a recording about Jimmie, not a tribute to him," Crouch says. "A tribute about his life and demons."

Once gathered in Burch's studio, the core members of the band — including Crouch, Kaplin, Perkinson, drummer Justin Amaral, and pianist Jen Gunderman, whose licks and flourishes summon an encyclopedia of prewar pop music — set about creating a sound that contained all the elements of Rodgers' music, and the feel of the songs, without slipping into imitation. Joining them was a remarkable list of guest players, in addition to the guest spots by Bragg, Feoranzo and Langford: revered guitarist/producer Richard Bennett, Tim O'Brien, William Tyler, Dominic Davis from Jack White's band, trombonist Roy Agee, guitarist Jack Silverman, and Garry Tallent from the E Street Band on tuba — a thrill for Springsteen fan Burch, who was going for something of the Salvation Army Band feel of "Wild Billy's Circus Story" from The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle.

Burch says the band members functioned almost more like a film crew, working to serve the singer's mood as much as they played the melodies. On "If I Could Only Catch My Breath," Crouch found himself "going for bass notes that hopefully feel like someone trying to catch their breath from down deep — you know, when they're breathing from the abdomen."

"The subject matter was coming from a real place," he says, "so I was trying to see it as a movie or if I was reading an autobiography."

Above all, though, Burch wanted the record not to be stiff and joyless. Songs like "Gunter Hotel Blues" and "Cadillacin' " have a spark of wit and spontaneity that fans red-hot when the group plays live. On Thursday night, Feb. 25, the group wraps up a monthlong residency at The 5 Spot in East Nashville, where Burch has been testing the new album live (and where Kaplin begins his own weekly residency March 3). The band's been mixing songs from throughout Burch's 19 years of albums — gems like "Monterey," a California sunset of a country ballad from Pan-American Flash, and the torrid rumba "Waiting for My Ship" from 2009's Still Your Man — with Meridian Rising's more conceptual material.

Paul Burch at The 5 Spot

Paul Burch at The 5 Spot

It testifies to the strength of the Jimmie Rodgers songs that the night registers not as a musical lecture but as one rollicking celebration, with Kaplin's dexterity on everything from mandolin to Resonator guitar to fiddle threading the many genres together, obliterating any distinction between highbrow and lowdown entertainment. Burch is fond of quoting Kaplin's maxim that "the difference between a violin and a fiddle is that you don't spill beer on a violin."

"There were really no rules," Burch says. "Like, I was never saying, 'There would be no drums in 1927,' because there was; they just had no way of dealing with the hot temperature of the drum coming through the very early microphone. So I wanted there to be as much fidelity as possible. Because if one imagines Jimmie in Coney Island, or going to a bunch of bars, or with Laurel and Hardy in Hollywood going to [the classy restaurant] Musso & Frank's, talking about making movies, if they went by a jazz band playing on the street, or playing in a hotel ballroom, it would've been rockin'. So there's no reason for us to hide that fact."

The record has already received strong notices from early listeners such as NPR critic Ann Powers, who spotlighted "Meridian" last fall on the public-radio giant's "Songs We Love" feature. All that remains now is to introduce Meridian Rising the album to audiences.

"I'm hungry," Burch says. "I've never had the burden of having a hit, but at the same time I still have something to prove. I want to show my peers that just because I'm not selling a lot of records I'm part of their generation. So I just felt like, 'I've gotta do something good.' And there's no way to be heard if you're just going to do what everybody else is doing."

At his website, Paul Burch has an essay about Jimmie Rodgers' life and the story behind the Meridian Rising album with song links, an account of the trip to New York that secured his place in history, and a song-by-song timeline following the album's narrative.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com

Paul Burch at Tennessee Central Railway Museum.