At the center of Tommy Womack’s new album, There, I Said It!, is a seven-minute, conscience-spilling rant, “Alpha Male and the Canine Mystery Blood.” It depicts a man in his early 40s at home with his wife and young son, drinking his way through a six-pack and contemplating a handmade poster he saw stapled to a telephone pole.

The handbill advertised a show that night by Death Cab for Cutie and a second band whose name Womack made up, which serves as the song’s title. The guy can’t get the group’s name out of his head, and it sparks some wide-ranging thoughts. With an acoustic guitar and electric bass pressing a relentlessly driving rhythm behind Womack’s words, he remembers a time two decades earlier, when an intriguing band name would have been enough to get him to pay the cover charge and join the crowd at the front of the club’s stage—“just because I’m 25, and every day is a stone summer day,” Womack speak-sings.

That memory prods the singer to remember his bygone days: he too played in a rock ’n’ roll band once. His group always had work, his manager always had pot, and he “got laid quite a lot,” Womack sings.

The song’s narration pauses, and the drums and electric guitars kick in. Then the commentary flies forward, the lyrics taking one randomly hilarious turn after another. First, Womack takes on the music industry (“I bet their name was Menstrual Blood,” he says of the Alpha Males, “and the A&R guy said, ‘That’s no good. Make it Mystery, and we can target a broader-based, goth, dog-lover market.’ ”), then switches to his young son, his father and Jesus.

By song’s end, Womack acknowledges that he’s just a burned-out, balding, 40-ish fellow who saw a rock poster at 8:15 in the morning while walking to a crappy, $11-an-hour job. He once thought rock ’n’ roll would save his life and make him wealthy, loved and constantly entertained. Instead, he’s riddled with anxieties and burdened by responsibilities.

He secretly vomits in the toilet at work from his nerves, and the highlight of his day comes when he sneaks out of the office for a cigarette. To keep going, he thinks of the love of his family, yet he can’t help but imagine his son—who received a drum set for Christmas—living out the same dream that failed him. He envisions his son traveling the country in a rock band, “doing things only young people do, banging on the skins at Bonnaroo, rocking the dread heads dancing in the mud, before Alpha Male and the Canine Mystery Blood. God go with him. Amen.”

Indeed, this is Tommy Womack’s story—a longtime Nashville rocker who struggles with anxiety and to make ends meet while raising an 8-year-old son, Nathan, with his wife, former morning TV anchor Beth Tucker.

It’s also the story of thousands of other musicians who arrive in Nashville with a dream, most of whom never get a foot in the door and eventually give up. Others, like Womack, taste success, selling some records, drawing nightclub crowds and getting in a van to stump for the cause, only to wind up in their 40s with few other skills and no backup plan.

But Womack is a songwriter—one with more talent and nerve than most. In There, I Said It!, he tells his story in the most personal songs he’s ever written. Though the album is just now coming out—it hit the streets on Feb. 20—it has already, in advance, drawn Womack more airplay, more enthusiastic reviews and more concert bookings than any previous effort.

In other words, an album about how he failed in the pursuit of his dreams may give him the career he’s always sought. No one sees the irony more clearly than Tommy Womack.

There, I Said It! began when Womack hit bottom. In March 2003, five months after his 40th birthday, he walked through his home with clothes piled on both forearms. He looked down and couldn’t remember which pile was clean and which was dirty.

“All of a sudden I just threw all the clothes down, and I fell on the floor crying,” says Womack. “I called Beth at work lying in the fetal position and screaming, ‘I’m a failure!’ I’d been trying real hard for real long, and I wasn’t going to make it, and everybody knew it. I had a nervous breakdown, basically.”

Womack recalls the event one afternoon while sitting in a midtown Japanese restaurant. He’s as skinny as a wired teenager, his beard thick and untrimmed, his hair long and hanging over his glasses. But his eyes are bright and focused, his smile quick and regular, and his words clear and brave.

That dreadful morning, his wife rushed home from work and called a doctor, who saw Womack that day. “For months, I had crying fits and panic attacks,” he says. “Everything fell apart. I had to bag a whole string of gigs. I lost my booking agent. At my temp job at Vandy, I was making myself as useless as possible. I got my duties down to getting the mail and covering phones for the receptionist during her lunch shift. But I managed to get fired. You can’t have a receptionist at the front desk crying all the time. It disturbs people.”

Womack started seeing a therapist and taking Xanax. After several months of counseling, his doctor suggested hospitalization. Womack protested, but the doctor told him he was as depressed as any patient she’d ever treated.

“I spent one night in a mental ward,” Womack says. “I’d never been locked up in a room for any reason. I couldn’t sleep at all. It was exactly like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I hope to never go through that experience again.”

In August 2003, while watching his son swim at the YMCA, he noticed a voice mail on his cell phone. His wife had left a message asking him to call her immediately. She waited until he called to tell him she’d been let go from her job as spokesperson for the Tennessee Department of Safety.

Later the same day, his phone rang again. It was the Vanderbilt job placement service telling him there was a job opening in the political science department. “I got the job because the other two people didn’t show up for their interviews,” he says with a wry smile. “God knows I’m sure they wished someone else had. I was a flaky, 40-year-old pothead musician who hadn’t ever grown up. But I had to take the job. In one afternoon we went from Beth being the breadwinner, which she’s always been, to me being the one who had to take care of things.”

The job didn’t start well. “I was paired up with a lady my age who was a single mom and had worked hard just to get to her position,” Womack says. “I represented everything she would have every right in the world to resent. I offended her more easily than I’d offended anybody in my life.”

His co-worker made her displeasure clear, and Womack, in his fragile state, experienced anxiety attacks every day knowing he’d have to face her. “I was throwing up on the way to work and in the john at work,” he says. “It was absolute hell.”

Obviously, his depression didn’t help matters. “I thought I’d screwed up every opportunity I’d ever had,” he says. “If anybody has not been screwed over by the music industry, it’s me. I’ve had chance after chance, one at-bat after another. Nobody ever twisted my arm and made me get drunk before going onstage. No one made me do a show stoned. No one made me run at the mouth at the microphone not knowing what my point was. And, in the long run, I never gave the music industry a song it could use. Commercial is not a bad thing. The Sermon on the Mount is commercial. But what did I do? I gave the machine an eight-minute-long song about The Replacements.”

He stops, looking dead-on as his interviewer laughs. Womack just shakes his head. “Nobody ever screwed me out of anything,” he says. “I’d screwed up every opportunity I had. I felt it was over. I was toast. Those were the worst months of my life.”

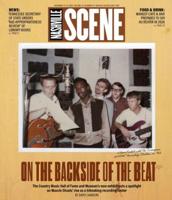

Womack grew up a preacher’s son in Kentucky. He first gained notice as co-leader of Government Cheese, an ’80s garage-rock band with a well-regarded live show based on witty, left-field songs like “Camping on Acid,” “Mammaw Drives the Bus,” “A Little Bit of Sex” and a searing cover of Jim Carroll’s “People Who Died.”

They appeared on MTV in 1988, and for several years, seemed a breath away from a bigger break. Womack later wrote a colorful book about the band’s experiences, and about growing up a rock fan in rural Kentucky—the hilarious Cheese Ifles: The Story of a Rock ’n’ Roll Band You’ve Never Heard Of.

By the time his book came out, Womack had teamed with friends Will Kimbrough, Mike Grimes and Tommy Meyer in the Bis-quits, a roots-rockin’ quartet named in part because all of the band members had considered leaving the music business before joining forces. They recorded one album for John Prine’s Oh Boy! Records in 1994.

“I’ve always thought it was Tommy’s job to write songs about things that don’t make sense,” says Kimbrough, who’s also gone on to release several solo albums between tours as the guitarist for Rodney Crowell and Jimmy Buffett, both of whom have recorded his tunes. “That’s always been what he does, only now he’s older, so the idea of what doesn’t make sense has changed. I’m blown away by these new songs, but I always expect Tommy’s songs to be brilliant. He’s like a hillbilly Woody Allen, and this album is a rock ’n’ roll equivalent of the film Little Miss Sunshine. It says, ‘This is a world of shit, but it’s all we’ve got.’ ”

In 1997, Womack started releasing solo rock albums featuring top-notch players like guitarists George Bradfute and Kimbrough, drummers Paul Griffith and Fenner Castner, bassists Dave Jacques, Brad Jones and Paul Slivka, steel guitarist Al Perkins and keyboardist Ross Rice. All four of his albums drew good reviews and “sold in the low thousands,” as he puts it. The last of these albums, a live recording from the XM Radio studios in Washington, D.C., was released a week before Womack’s nervous breakdown in March 2003.

In September 2003, a month after he’d started his second stint at Vanderbilt University, Womack got a call from singer-songwriter Todd Snider, who asked if he wanted to play bass in the aptly named Nervous Wrecks, Snider’s band. “Tommy was a wreck long before he met me,” cracks Snider, who says he thinks the devil bet God that if Womack took a day job, he’d quit music altogether.

“I first heard of Tommy through the Bis-quits, and I just loved his songs,” Snider continues. “You could tie ropes to his hands and feet and pull him apart with pick-up trucks, and a bunch of songs nobody else could’ve written will fall out.”

Womack jumped at Snider’s offer, and fortunately, his new Vanderbilt boss allowed him time off to make the shows. “I didn’t own a bass, I’d never played one professionally, and I said yes immediately,” he recalls. He learned 29 songs in a matter of days and played his first bass gig in front of a crowd of 1,000.

Womack wasn’t yet emotionally healthy. “I’d cry in the dressing room when nobody was there,” he says. In a Seattle airport, he had a second breakdown, ripping at his clothes and gnashing his teeth in front of his bandmates and other travelers.

But he kept the gig, playing with Snider and the Nervous Wrecks for more than two years. In November 2004, after blacking out through an entire gig, he quit drinking, and for the first time in his adult life, he no longer knows the phone number of a pot dealer. He also got to where he could sit through a movie all the way through without pausing a DVD or walking out into the lobby of a theater. He took that as a sign he was getting himself under control again.

Meanwhile, Kimbrough and Womack began doing duo gigs on the side, which led them to form another part-time side band that the two fathers called Daddy, with Griffith on drums, Jacques on bass and John Deaderick on keyboards. They recorded a series of live shows in Frankfort, Ky., and released them in 2005 as Daddy Live at the Women’s Club.

“All of a sudden, Will’s career was on the rise, and Todd was coming back up fast, and the spotlight on them bounced some light on me,” Womack explains. “I started getting my own gigs again. My music career came to life again without me doing a thing to solicit it. Before long, I was working every weekend and often during the week, with no booking agent. It was all coming to me.”

The first of the new songs that make up There, I Said It! came on Snider’s tour bus in Texas in the spring of 2006. “Nice Day” is a wistful, atypically sweet song for Womack about an afternoon spent at a friend’s house swimming in a backyard pool with his wife and son.

“I didn’t realize how good it was at first,” he says of the song. “I thought it was a navel-gazing, mealy-mouth confession of a wimp. It took me a while to absorb it because it came from this honest place I’d never written from before. From then on, the spigot was open. All the lyrics started coming from that same honest place.”

Womack asked Deaderick, who’s played in touring bands for the Dixie Chicks and Patty Griffin, if he would consider recording the new songs in his basement studio. “I’d never heard any of the songs until Tommy came to the house,” Deaderick says. “I wasn’t aware of the problems he’d been through, but listening to his lyrics, I put it all together. The songs just completely knocked me out. I jumped at the chance to make the record.”

With Deaderick as producer, Womack enlisted friends who played for free, including Kimbrough on guitar, Slivka on bass, Castner on drums and Lisa Gray on harmony vocals. Former Black Crowes member Audley Freed plays guitar on a couple tracks, and John Gardner replaces Castner on drums for two tunes.

The album opens with the somber “A Songwriter’s Prayer,” where Womacks asks God to send him some tunes. What follows includes the self-explanatory “I’m Never Gonna Be a Rock Star” and two songs about his struggles with his day job, “Fluorescent Light Blues” and “Cockroach After the Bomb.” There’s the hard-rocking blues about instability, “Too Much Month at the End of the Xanax,” and another written in his analyst’s office, “I Want a Cigarette.” The album closes with a blessing about how life can get better, “Everything’s Coming Up Roses Again.”

“In a very leftist way, I consider this my first Christian record,” Womack explains while finishing his sushi. “It starts with a prayer and ends with an answer. Of course, I question the resurrection on track nine, so for a Christian record, it’s pretty edgy. If they have a Dove Award for most blasphemous record by a male artist, I’d be a shoe-in.”

The day of his Scene interview, it turns out, was his last as a full-time employee at Vanderbilt. He moves from a full-time office worker who does music on the side to a full-time musician who does part-time office work. In other words, he’s rejiggering the dream he first started to live in his 20s with Government Cheese and, in his own way, showing all the other dreamers, especially those with true talent, that there can be another way to become a small but important part of the big machine. He may never be a rock star, but by writing songs no one else could’ve written—songs drawn from his own experiences and own point of view—he may once again be able to support his family. As Womack puts it, all he’s ever wanted to do was earn as much money from his profession as an average-income insurance agent.

“I’ve been crazy all my life,” Womack says while paying his bill. “I was the crazy kid in high school. I was ADHD before anybody knew what it was. But now I’m a crazy guy who’s making a living at it. It’s been a while now since I’ve asked myself, ‘Tommy, why are you doing this?’ It’s because I know the answer now. I write crazy songs, and I perform them. This is what I do.” Tommy Womack plays his CD release show Friday, Feb. 23 at The Basement.