Commerce Street facing Eighth Avenue

On Aug. 19, 1963, the Nashville Tennessean newspaper reported a raid on a Commerce Street bar called Juanita’s Place. Twenty-four people were arrested for disorderly conduct by loitering, one for public drunkenness and one for operating a disorderly house. But the real motivation behind the raid is hinted at in another arrest: “disorderly conduct by immoral conduct.”

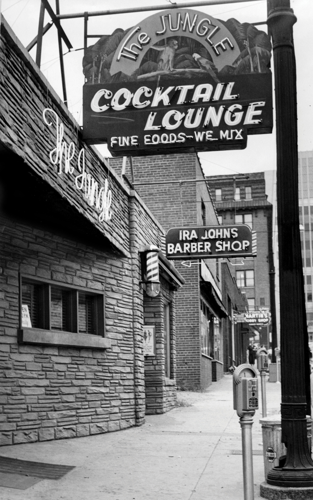

The paper lists the names and addresses of all 27 people, including the bar’s proprietor, Juanita Brazier — the one with the disorderly house. Juanita’s Place was one of the first gay bars in Nashville, second only to the The Jungle, which operated next door. A historical marker will be unveiled at Commerce Street and Seventh Avenue North to memorialize the bars at 11 a.m. on Friday, Dec. 7. The public is invited to attend.

“You had to be kind of brave to be gay back then,” says John Bridges, the driving force behind making the historical marker a reality. “But you wanted to have fun, too.”

Warren Jett opened The Jungle, a bar and restaurant, in 1952. People from Capitol Hill would come in for lunch, and later on in the afternoon, the bar would fill with gay men. Jett also owned a small beer joint next door called the The Leopard, and he hired Juanita Brazier to run it. She soon got her beer license and reopened the spot as Juanita’s Place.

Bridges, who contributes to the Scene’s sister publication NFocus, set his mind to applying for a marker with the Metro Historical Commission and spent a year following breadcrumbs in the Nashville Public Library archives. He checked the police and sheriff’s department archives, and he says he inquired in “basically every office in Metro.” Bridges was an occasional patron of The Jungle and Juanita’s, but he spent more time in a dance club on Franklin Road called The Warehouse.

The Jungle in 1954

“The gay world has changed so much lately,” says Bridges, “and there are younger people out there who don’t know what it was like.”

Bridges says it’s easier for LGBTQ youth to meet one another now than it was in the days of The Jungle and Juanita’s. He says there were “15 or 20” bars in Nashville that gay people frequented, and they tended to cater to specific tastes — he remembers cowboy bars, leather bars and preppy bars. “There are three now,” says Bridges. “Why should they [gay singles] go out? They’ve got their phones to work with, and they can go to any restaurant they want and hold hands.”

Joe Heatherly patronized The Jungle and Juanita’s starting in the late ’60s. “Juanita was redheaded ’til the time she died — fire-engine red,” he says. “And she had a really sparkling personality. Everyone loved her. She was a mother to all the guys that went in.”

“For a while,” says Heatherly, “it was a scary place, because you never knew when the police were going to come in and take you in for being in that establishment — for no crime other than being gay.” Brazier would often bail her patrons out of jail and march them back to the bar, Heatherly says. In those days, The Tennessean printed the names, addresses and sometimes employers of anyone arrested during a raid. But it didn’t keep people from going out. Later, in 1971, Heatherly and his partner opened a gay show bar, The Watch Your Hat and Coat Saloon, on Second Avenue.

Bridges says patrons also faced issues with towing companies. Legally parked patrons would have their cars towed away, having to pay exorbitant rates to retrieve them.

Nevertheless, they kept returning. “These people had to be very brave to go there,” says Bridges. “But they wanted to go there because they wanted to be together.” He chuckles. “They also wanted to pick someone up and take them home, but they were very brave. … It was a difficult time to be alive and be gay, but it was a fun time too.”

Brazier died in 1995, and the late Scene editor Jim Ridley memorialized her in a detailed and colorful history of Juanita’s that is still worth reading today.

As Bridges finished up his research, he sought a grant to pay the historical commission for the cost of the marker. He found support in the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee’s H. Franklin Brooks Philanthropic Fund. Brooks, a dear friend of Bridges’, was a professor at Vanderbilt University, and he led a dialogue that resulted in including LGBTQ students in the university’s anti-harassment policy in the ’80s.

“These bars in Nashville were before their time,” says Michael McDaniel, a senior donor services adviser at the Community Foundation and also the Brooks Fund liaison. He notes that the bars weren’t secluded, tucked away somewhere off the beaten path. They were right downtown, blocks away from the bus station and in the midst of other bars, restaurants and flophouse hotels. When McDaniel moved to Nashville in the mid-’80s, some straight patrons also frequented the bars. “We could all come under one roof and celebrate each other and enjoy each other’s company,” he says.

“It didn’t matter who you were or how much money you had,” says Bridges. “It didn’t matter if you were straight or married. … It was a place where everybody gathered.”

The block was leveled in 1983 to make room for the Renaissance Hotel. Both bars moved to different locations, and besides, they were no longer the only places where gay men could gather.

But before that, says Heatherly, “because of having to be closeted, the only place they could truly be themselves was when they went to the bar.”

“The Jungle and Juanita’s were like being in a comfortable, home-type place,” he says. “You could relax and be yourself.”