With every year comes the inevitable loss of community leaders, civic builders and colorful personalities who help give Nashville its character. In our annual In Memoriam issue, the Scene recognizes some of the people the city lost in 2012, vibrant threads we will miss in the city’s tapestry. Some were prominent social and civic figures known to all; some were familiar only to a lucky few. Below, we commemorate lives that left an indelible mark on others, and on the city they called home. Read, and remember.

MEDIA

ED STRATTON

1911-2012

The Voice of Emma's

By Jim Ridley

If you grew up in Middle Tennessee within the past four decades, you have certain TV taglines and jingles you can recite like the Pledge of Allegiance. Remember "The height of a piggy's ambition / From the day he is born ... ?" Or "Take HAWM! a PAY-uh-KIDGE! uh TAYUN-UH-SEE PRAHHHD!" Topping them all, though, was this elegantly simple four-word incantation burned into the brains of most any Nashvillian: "Emma's — the supoilative florist."

That's right — not "superlative," supoilative. The inflection was the trademark of Ed Stratton, the Nashville announcer and advertising man who not only devised the tagline but read it on TV and radio for nearly 30 years. West End's venerable Emma's Flowers and Gifts, founded in the 1930s, was the very first client of the Merry Sounds Advertising Agency he'd started after retiring from WSIX. As he told Kay West in a 2000 profile, he'd woken up in the middle of the night with a word ringing in his head: "superlative." He had to look it up. The next day, he told Emma's owner Haskell Tidman Sr. he'd hit on "a $50,000 idea" — a campaign that would use landmarks from around the world to brand Emma's as "the superlative florist."

"Stratton may have had the $50,000 idea," West wrote, "but Tidman had the million-dollar hunch that his friend's voice would be perfect for the spot." Thus, in 1983, was Nashville broadcast history made. Stratton had been a college man at Sewanee in the 1930s, an Army machine-gunner in the South Pacific during World War II, and a successful ad man whose record-setting career spanned seven decades interrupted only by the war. But it was that mint-julep drawl and those four words that had people stopping him in stores and restaurants until he died at age 101.

Last year, the florist held a 100th birthday celebration for Stratton in its back room. The guest of honor sat with hands clasped in a rigid chair, mostly silent. But when those present begged him to say the magic words, he summoned a dramatic pause and said, "Emma's — the supoilative florist." He beamed, wholly at peace with his claim to fame.

DAVID HALL

1954-2012

Program director; DJ, WRLT-FM Lightning 100

By Abby White

One of the first things I did when I arrived in Nashville in 2001 was scan the radio. Quickly bypassing the various commercial country and pop options, I landed at 100.1 FM. It was like someone had made a mixtape just for me: I heard Jeff Buckley, The Beatles, Patty Griffin, the Dandy Warhols, R.E.M. and then a band I'd never heard of — but instantly loved — Jump, Little Children. What was this? Was this a college radio station?

A man came on to identify the station as WRLT Lightning 100. His name was David Hall, and I learned that David Hall rocks y'all. I knew I had to somehow be a part of this radio station, so I showed up at every event they sponsored and stalked GM Fred Buc until he hired me as an account executive.

As a music nerd fresh out of college, this was a dream job. Working with a legend of Nashville radio — who happened to be one of the biggest Beatles fans I'd met — was just one of many job perks.

Hall, who served as program director of the locally owned, independent radio station, curated the extensive playlist with longtime music director Rev. Keith Coes. Hall, who started at WRLT in 1993, hosted the afternoon drive-time shift, and served as emcee for the popular live broadcast of Nashville Sunday Nights from 3rd & Lindsley every week.

Hall started his career in broadcasting in 1972 at WNBS in Murray, Ky., where he attended college at Murray State University. After a four-year stint at WABD in Fort Campbell, Hall joined WKDF, where he worked for eight years as a disc jockey, music director, and assistant program director. From 1988 until 1993, he held the same roles at classic rock station WGFX The Fox before joining WRLT.

"I didn't realize how famous he was," says Wells Adams, who took over Hall's drive time slot. "After he passed, people who didn't know him personally were calling in and expressing their condolences, so that was really heartwarming to hear. ... David had one of the best radio voices you'll ever hear. Looking back, I don't know if there will ever be another voice like that in radio in Nashville."

JAYNE ROGOVIN

1959-2012

Media programmer; publicist

By Kay West

Jayne Rogovin was a self-described "nice Jewish girl" who spent her first 11 years in Long Island, N.Y., then moved with her family to Miami. She majored in broadcast journalism at the University of Florida and minored in surfing. After graduating she moved from city to city, station to station, including one short stint in Nashville at WTVF-Channel 5.

Her last TV news post was a CBS affiliate in Dallas, where in early 1993 she spent nearly two months camped in a trailer outside Waco, Texas, covering the Branch Davidians siege until the horrific fiery conclusion that killed 76 men, women and children.

Sickened and disheartened, she packed her bag, her tapes, and headed back to Nashville. She boarded her horse at a barn in Franklin and switched gears from hard news to entertainment, pursuing work in the music video field. I met her in December 1994 when my then-husband Steve West teamed us to work together on the script for the first annual Nashville Music Awards, aka the Nammies, which he was producing for Leadership Nashville. We worked side by side for nearly two months, and became fast friends. After my divorce in 1997, we became even closer, partnered on many more projects, and were usually each other's plus-ones at shows and events.

When video work dried up, Jayne started her own media and marketing firm — The Jayne Gang. She was a driving force promoting the Americana Music Festival, bought a house in a very sketchy part of East Nashville and helped form their first neighborhood association. Jayne tackled every challenge with equal parts proficiency and pragmatism. Not knowing how to do something never daunted her — she simply got it done. She frowned on incompetence, but had a tender heart and a wicked sense of humor. Jayne was fearless, independent and resilient. She called her own shots.

Which made the diagnosis of stage IV breast cancer in July 2010 particularly hard to process. When I got to her house that day, she was sobbing and terrified, and asked me to help lead the fight she knew was ahead of her. She called me The General. One of the first things we did was order knit hats embroidered with the words "Fuck Cancer" for the group of four that went with her to doctor appointments and chemo at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center.

Jayne was dying, but for the next 17 months she lived large and joyful. She rejected pink ribbons, but embraced fun, adventure, discovery and travel, no matter how tired the disease and treatment left her. In January, she went on the Delbert McClinton Blues Cruise with her boyfriend John, posting photos of herself basking in the sun on deck, insisting on horseback riding at a port stop.

When I picked her up at the airport, it was clear she had declined. She was admitted to Vanderbilt on Feb. 5, still optimistic that her worsening condition was just an infection she would beat. When tests showed several days later that more treatment was not an option, we all cried. The next day, she stopped eating and asked for medication for her intense pain. From then on, she mostly slept, covered with a friend's quilt. One afternoon, she sat straight up with a start, looked right at me and demanded, "Where is my wallet?" I brought it to her. "Where are my credit cards?' I pulled some out. "Where is my license?" I showed it to her. She lay back on the pillow and closed her eyes. "OK," she said. "I'm ready to go."

Those were the last words she spoke. She passed away at dusk on Feb. 13, loved ones holding hands over her, and a bag of barn dirt tucked under her back, a final goodbye from her horse Diva.

Jayne lived life on her own terms and left it that way too, with immense strength, grace and dignity — and not until she knew she was ready to go.

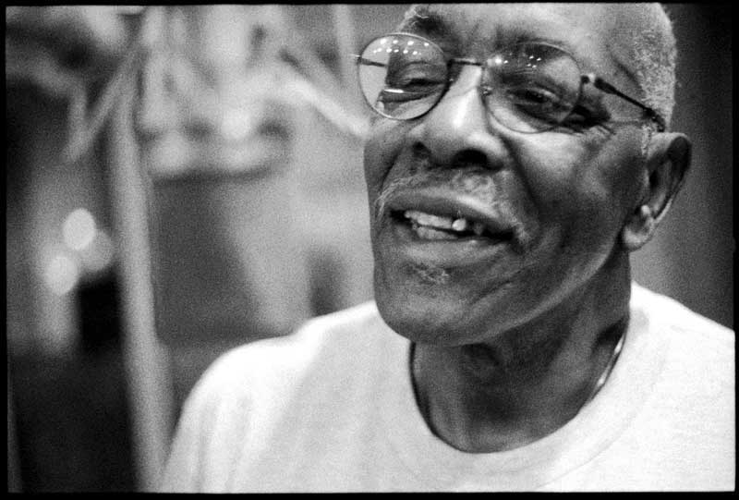

Scooby (left) and Dolewite

CURTIS "SCOOBY" SENIOR

1978-2012

DJ, 101.1 The Beat

By James "Dolewite" Raymer

I first met Curtis Senior as a freshman at Georgia Southern University, in a dorm known as Oxford Hall, which provided the worst living conditions on campus. My first memory of him was on the dorm's basketball court. He was far from the best player out there, nowhere near the worst, either — but he talked more trash than everyone else on the court combined. And he was the best trash-talker I ever came in contact with.

As I got to know him throughout the year, he told me he was interested in joining me one evening on my college radio show, which ran on Saturday nights from 3 to 7 a.m. Week after week, he was nowhere to be found in the middle of the night when it was time to go to the station, but eventually he showed up — and the on-air chemistry between the two of us was there from the first time we popped the mic. Thus Dolewite and Scooby were born.

Throughout college and our run on 101.1 The Beat in Nashville, Scoob never forgot the name of a listener or old friend, and was the guy everybody turned to for advice in a time of need.

He was my business partner for more than 15 years, but more importantly, the best friend I could ever imagine having. And more than that, he meant something to the people of Nashville. He spoke to kids in the Metro Nashville school district and never said no to a charity event. How he spread himself so thin is beyond me, but he did and never complained about it.

On Feb. 18, Curtis passed away unexpectedly from a rare disease called sarcoidosis. He will always be remembered first for his contributions to the youth of this city, and second for his enormous personality and ability to entertain on a daily basis. Forever in our hearts, forever my brother, Forever Scoob!

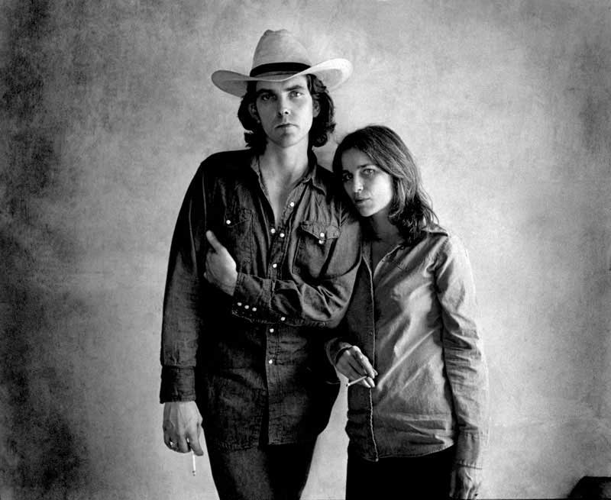

Chris and Katie Neal

CHRIS NEAL

1972-2012

Music journalist

By Katie Neal

Not long after we started dating, Chris arrived late to pick me up for dinner. He apologized profusely and handed me a stack of CDs, explaining he'd lost track of time burning a bunch of music that he thought I'd like — a Tori Amos EP, Ani DiFranco bootlegs, some Britney Spears dance remixes. "You'll soon learn," he said, a little sheepishly, "that this is how I show my affection."

Truer words were never spoken. Very little in life made Chris Neal happier than sharing music, with friends or strangers. As a writer first for Country Weekly and later for the Scene, Performing Songwriter, M Music & Musicians and more, he cherished the opportunity to endorse great artists, whether he'd worshipped them as a young boy in rural Virginia, or their debut album had just crossed his desk and captured his fancy. (He championed Little Big Town early on, which makes their long-overdue success all the sweeter.) Like a human Pandora, he loved introducing others to artists he thought they might like based on the minutiae of their musical tastes, whether they relished a robust horn section or had a fondness for slow blues. Recently, I came across an 8-track tape of gospel music among Chris' things, and remembered he'd been hoping to convert the out-of-print album to CD for his mom at her request. In his mind, that was one of the kindest gestures he could make: to enable someone to experience the transcendence he believed only a beautiful piece of music could deliver.

In this way, for Chris music sometimes served as an emotional shortcut. Though he had a remarkable way with words, talking didn't come easy. He dreaded cocktail-party chatter, yet he was never intimidated by an interview with a musician he admired. After all, they shared a passion. That allowed him to talk to giants like Sting, Stevie Nicks and Dave Grohl about incredibly personal, even painful aspects of their lives — divorce, loss, failure, death — with utter confidence and compassion.

Many of these conversations ran not only surprisingly deep, but also both ways. I'm not sure how many close friends Chris had confided in about his fear of turning 40. But when he happened to interview Shirley Manson on that birthday, he found himself on the receiving end of some big-sisterly advice about embracing middle age. Somehow, the context of music could open doors he otherwise found daunting.

One of the last albums Chris bought me was Nicki Minaj's Pink Friday. I think he was thrilled that after nine years together, his wife was finally beginning to appreciate his beloved hip-hop, albeit in a glittery, MAC-lacquered package. One day I mentioned I was obsessed with the album, but hated "Roman's Revenge," a track featuring Eminem and his ever-present misogynistic rage. A few days later, a burned CD appeared on our coffee table. "What's this?" I asked. "Oh, I burned Pink Friday and took off that track for you," he said. "And I added a Britney remix that Nicki sings on."

Some men send flowers. Music was always Chris' grand gesture. And lucky for me — for anyone missing him — the music lingers.

Media Remembered

Pat Harris, 88, journalist whose résumé included nearly three decades as Reuters' Middle Tennessee correspondent and more than 25 years writing for Time magazine; served as Chicago press aide to Adlai Stevenson during his presidential run against Dwight D. Eisenhower; 12-year employee of the Tennessee Department of Education.

Charlie Lamb, 90, colorful music journalist who founded the city's first trade publication, Music Reporter, noted for its country music chart and bulleted singles; ex-carnival barker born to a trapeze-artist mother and magician father; went on to careers as manager, entertainer and occasional actor.

ARTS

WILLIAM GAY

1941-2012

Writer

By Randy Mackin

"Daddy always wanted to see a ghost."

William Gay's daughter Lee offered that revelation when we met for lunch a few months after her father's death in February.

At first I was surprised. William and I never really spoke about the afterlife, but I soon put the matter into the context of William's incessant curiosity: A ghost would have proved for him that there was some existence after this one, that there was a plane "beyond the pale," to use one of his favorite phrases.

William said that writing should always be about something larger than itself, and he was the pernicious student — three novels and a short story collection later — trying to figure out how an artist was able to accomplish a particular effect. On one of my last visits with him he was rereading A Farewell to Arms, immersing himself in Hemingway's technique.

And while we lament the loss of his talent, his work will endure. All we can long for is that the language he was laboring over at the time of his death (two novels, The Lost Country and The Wreck of the Tennessee Gravy Train, and a handful of stories still in longhand) will someday find their way into print.

William, who always wanted to see a ghost, is one now, but it's a haunting we should cherish.

I suspect we'll see him again leaning against a column of some plantation-era home — the paint peeling and the eaves sagging, waiting for a handyman to set them right.

Or his spirit will be the shadow behind Southern fiction still to be written since his influence is undeniable among the best creators of the written word today.

When William left this world and entered the next, I hope what he found was this place which the autobiographical Edgewater from The Lost Country discovered upon waking after a forlorn night in the woods:

"But his heart was lifting and his feet felt fleet and light. The day was new and unused and this day was one that had never existed before and he saw it as a footpath that led into a world that was sensual and manyfaceted and complex beyond his understanding, but for the moment he was comfortable in it and roofs and shelter and ill weathers were things of no moment. He thought the only dwelling he needed was the unconfined and unwalled world itself."

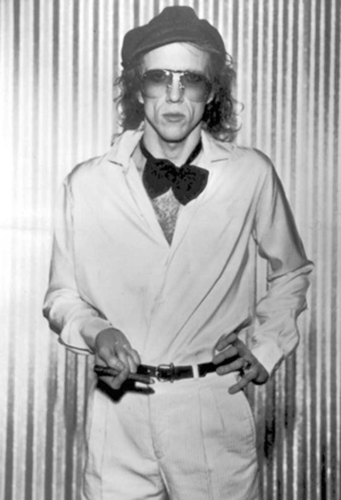

KARSTEN SOLTAUER

1960-2012

Visual artist; musician

By Kate O'Neill

If anyone could have appreciated the absurdity of trying to distill a colorful, well-examined life down to a few hundred words, it would have been Karsten — my husband, my love, my partner, my best friend. After all, no one I've ever known has had a keener sense of the absurd, or a personal brand more synonymous with recognizing it.

In other words, if anyone could've actually managed the task well, he'd have been the guy.

Karsten was charming, engaging and unique, in large part due to his ability to observe what few others seemed to see. He had a powerful ability to associate seemingly random ideas, an intense curiosity, a wickedly clever wit and a knack for finding the bizarre among the mundane — all of which afforded him a rare gift for reducing abstract ideas to a concise but comical essence. It was the first thing I noticed about him when I met him at a party 15 years ago. (Well, that, and I thought he was cute.)

He incorporated his love of the absurd into his creative output, too. He delighted in spoiling our cats, constantly coming up with new ways to entertain them or indulge them. When he determined that they enjoyed the feeling of being gently shaken, he invented and built a "cat jiggler," enlisting various friends to help develop and improve the mechanics over bourbon-spiked, laughter-filled evenings.

He was a conceptualist even more than a creator, but what he did create — from music to art — was meticulously executed. For that matter, his studio workspace was a visual metaphor for discipline applied to creativity: walls cluttered with reference images but carefully organized, tools hanging in rows, supplies neatly ordered, found objects curated on window ledges in a satirical diorama of a Nativity scene or arranged into a phallic shrine. It was a highly usable space, but also an entertaining place to visit.

His final work, a mixed-media assemblage piece titled Cosmic Primate (An Atheistic Evolutionary Bedtime Story), was a better summary of his personality and perspective than anything I could describe in words. Over a backdrop of chemical symbols, star charts and technical illustrations, Karsten applied the front-and-back painting technique used in cel animation to depict psilocybin mushrooms, a grinning ape and fire, in a triptych narrative of evolution and aspiration that is both hopeful and haunting.

In the days and weeks after Karsten died, a great many friends shared memories and impressions of him through blog posts, Facebook, videos and so on. With remarkable consistency, these themes recurred: He was an unmatched conversationalist; he was a kind and compassionate friend; he was a provocative artist; he was an exceptionally fun party host and guest. That seems as it should be. His legacy among friends, our neighborhood and the community is large, quirky and full of color.

But to me, Karsten will always be most memorable as the guy standing off to the side of the room, grinning, knowing, summarizing the conversation in a punchline that knocks all the pins down and perfectly captures the moment.

JANE GOODMAN BELL

1941-2012

University administrator; former gallerist

By Christine Kreyling

Jane Bell knew how to give comfort. I learned this even before I moved to Nashville in 1985. Her husband, Vereen, recruited my husband, Michael, to teach American literature at Vanderbilt. Jane insisted we stay in their home while we house-hunted. Through one of the city's worst droughts, she faithfully watered our potted lemon trees — émigrés (like herself) from New Orleans — that lived in their backyard until we had one of our own. These small facts signify her essential nature: supremely hospitable, generous way beyond the social necessities and responsive to need in a finely nuanced way.

It was paint chips, however, that forged our friendship. In the early '90s, Jane asked me to help pick out new colors for her walls. I don't recall why. Perhaps she sensed a particularity about design details equal to her own.

Home improvement has a life force all its own. Thus we moved from painting to reupholstering to refinishing to relighting to kitchen renovation. During all this, I learned that Jane was a pit bull — a small, dark, polite one — about getting things exactly right. I discovered her edgy sense of humor and willingness to use the F-word when called for. I became as familiar with her premises as my own.

Finally, it was time to hang art. Having owned and operated the Portfolio gallery — Jane called it a shop — she and Vereen had a fine collection of 20th century prints. When we laid out the plan, however, she made sure it included pieces her children made in school and their favorite posters. Most telling was a whole wall of photographs of family and friends. Jane was a collector of people.

She collected them during her work at the Race Relations Information Center and Vanderbilt's Sarratt Student Center. Then there were the far-too-numerous-to-count gatherings she and Vereen hosted for the Vanderbilt English department, for writers reading at the Southern Festival of Books, to welcome back friends who'd left town but whom they wouldn't let go.

The sense that Jane's house was my house persisted until her end. Two weeks before she died we talked, about the house, of course. Whenever a new lamp or bedspread was in the offing, she'd call. And I'd feel needed. Jane Bell was good at that.

Arts Remembered

George Lindsey played a taxi cab driver on an episode of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour and was the voice of a basset hound in The Aristocats, but will always be best known as "Goober," the slappy-dancing country rube — first on The Andy Griffith Show and later on Hee Haw. He died in May at 83.

[page]

MUSIC

DONNA SUMMER

1948-2012

Singer; songwriter; actress; disco diva; glamour icon

By Jason Shawhan

It's January 2011, and mourners stand outside the basement of a rural Gallatin chapel, grieving the death of Juri Bunetta, the 19-year-old son of music industry veteran Al Bunetta. It is a horrible day, but in the midst of heavy silence, a sound of unearthly beauty turns heads upward toward the church: a version of "Amazing Grace" sung a cappella, as if sorrow had found its pitch. Those who cannot see inside ask who could possibly be singing. When the answer comes back, they nod, all explained.

With Donna Summer, there was always the voice. Sprung from Boston gospel, musical theater and polyglot barroom gigs all throughout Europe, the artist born LaDonna Gaines was one of the great musical personalities of the latter 20th century. Whether fate, circumstance or the hand of a merciful God brought Summer together with the musicians who would become the Munich Machine, it began a collaboration that would personify the revolution of sound, sass and sex sweeping the world. Donna Summer didn't necessarily need disco, and disco didn't necessarily need her, but together they made history. "Love To Love You Baby," written with producers-musicians-collaborators Pete Bellotte and Giorgio Moroder, took the nascent idea behind what would become the remix and made it the centerpiece of that holiest thing of all that is Rock — the album.

The tension between embodying the sound of a sensual, strobelit revolution and a religious rebirth led Summer away from the sultrier, moan-based subdivisions of the nightclub world. With Bellotte and Moroder, in 1977, she galvanized dance music by welding the energy of the 4/4 disco strut to the synthesizer. It is impossible to overstate the influence of “I Feel Love,” from that year's I Remember Yesterday album. Conceived as a whirlwind through the styles of several decades' hit parade, served up with some accented hi-hats and sequenced boom-boom, that LP revealed the musical versatility of both the Bellotte/Moroder/Summer songwriting team and Summer as an artist. And what they'd designed to represent the sound of the future — “I Feel Love” — became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Never a force of nature like Grace Jones or a powerhouse belter like Loleatta Holloway, Summer nevertheless became the perfect incarnation of the disco era. She was a Broadway diva in her ability to move between personae and performances, changing moods and tones with a versatility splendidly suited to the producer-driven era of disco. She kept her sound broad and evolving, so that even before the shamefully homophobic and racist disco backlash of the early '80s she was already keeping radios humming and dancefloors moving with rock, reggae, new wave, and proggy flourishes. Summer's body of work is the single degree of connection between Jon & Vangelis and Stock Aitken Waterman, between Michael Jackson and Dolly Parton, between Barry Manilow and Jimmy Webb.

She never stopped having hits. That's not the ultimate measure of any artist's success, but it is something to keep in mind. Even in the 17-year stretch between albums of all original material, she maintained her presence on the charts — a new single added to a hits compilation, a promo 12” here and there, just to let the dance floor know that the Queen was still aware and feeling it.

When Donna Summer died earlier this year from lung cancer, she left behind a career distinct from so many others who worked in the pop/dance idiom. She was a star, and always on her own terms. You can see the throughline between the classic output of the Moroder/Summer/Bellotte team and hear its syncopated pulse in the work of countless contemporary artists — the monster hooks of Lady Gaga, the glitter-stained and whiskey-soaked arpeggios of Ke$ha, the serrated waves of The Knife. It's nearly impossible to conceive of modern electronic music without the inciting catalyst of “I Feel Love.” Today's marketplace would let that one song serve as a career before moving on to something new. Summer never stopped finding stories to tell and songs to sing.

A periodic resident of Nashville and Franklin, Donna Summer is buried here. And though her career was built on weaving in and out of the nonstop thump of night rituals, you need only look to her performance of the Oscar-winning song “Last Dance" (in 1978's Thank God It's Friday) to realize the effectiveness and power of a graceful finish.

Someday cybernetic intelligence will happen upon the remnants of this world, long after human life is gone. In its attempt to reconstruct the tangled histories of human and mechanical development, it will come across "I Feel Love," or Act Two of 1977's Once Upon a Time. Awestruck at the soul arising from all those synthetic components, it will hail the one called Donna Summer as a prophet — the voice of interface. The sound of synthesis. The ghost in the machine.

ISAAC "DICKIE" FREEMAN

1928-2012

Gospel singer; member, The Fairfield Four

By Ron Wynn

Isaac "Dickie" Freeman was an exceptional singer, gifted with one of the finest bass voices in spiritual or secular music. Freeman, who died in October at 84, was the anchor on a host of superb recordings and performances by The Fairfield Four, a landmark ensemble whose show on WLAC was distributed nationally by the CBS radio network. But Freeman made equally magnificent records with other gospel groups, among them The Golden Tones, The Kings of Harmony and The Skylarks, returning to Nashville in 1962.

During Freeman's later days with The Fairfield Four, after a 1980s reunion, they performed with such rock and country notables as Elvis Costello, John Fogerty, Lyle Lovett, Amy Grant and Johnny Cash. They gained new fame and cachet with contemporary audiences through an appearance in the film O Brother, Where Art Thou? and on the film's soundtrack. They earned a Grammy for the spectacular album I Couldn't Hear Nobody Pray.

Despite The Fairfield Four's crossover success during Freeman's latter years, neither they nor Freeman have gotten the widespread mainstream fame given other seminal groups from their era — The Soul Stirrers, Blind Boys (both Mississippi and Alabama), Swan Silvertones, Pilgrim Travelers or Dixie Hummingbirds. The Four are in the Gospel Music Hall of Fame. But they have not yet been voted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an influence, despite their noticeable impact on numerous R&B groups. Author/historian/journalist Bruce Nemerov says they were unquestionably the equal of any ensemble, but maintains that Freeman's devotion to gospel was such that he didn't actively seek that type of attention.

Irrespective of crossover success, Freeman was a singular vocalist.

"As a singer, he was incredible," Nemerov says. "His tone was pure, his range vast, and his sound impeccable. They used that voice to ensure the group stayed in key, and the harmonies were right. He was the complete bass singer."

EARL SCRUGGS

1924-2012

Banjo legend

By Randy Fox

It's a testament to the talent and influence of Earl Scruggs that just two words, "banjo music," immediately evoke the sound of Scruggs' lighting-fast bluegrass breakdowns. Few instrumentalists in the history of music have had the sweeping influence on their chosen instrument as this country boy from the hills of North Carolina, who in the words of George D. Hay, "made the banjo talk."

Although Bill Monroe & his Bluegrass Boys had been pushing the limits of traditional string band music for several years, it was the addition of the 21-year-old Earl Scruggs to the band in late 1945 that solidified the musical style soon to be known as bluegrass. It was the same year as the start of the Atomic Age, and when Scruggs first unleashed his three-fingered rolls on the Grand Ole Opry stage one cold December night, an A-bomb might as well have hit the Ryman.

In a way Scruggs launched an arms race in the ranks of hillbilly music, as bands and record companies scrambled to find the secret of this new style. Banjo players who had long ago mastered the traditional two-fingered picking styles suddenly found a use for their middle finger that didn't start fights. After a little over two years with Monroe, Scruggs left to form the world's second bluegrass band with guitarist Lester Flatt.

Flatt & Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys soon became the most popular bluegrass act in the world by tapping into the growing folk music scene and through many television appearances. Along the way, the "Scruggs Style" became the standard for almost all other banjo players.

But Scruggs' instinct for innovation didn't allow him to sit still. After a successful 22-year run, Scruggs split with the more traditionally inclined Flatt and formed the Earl Scruggs Revue with his sons. He became a mentor for a new generation of bluegrass musicians. He filled that role with class and generosity until his last days, constantly expanding the vocabulary of the instrument he taught to talk.

BOB BABBITT

1937-2012

Bass player; member of Motown Records' studio band The Funk Brothers

By Tim Marks

When I first became interested in music, it was a slow start. I didn't know any musicians, and there were few resources close to the small Michigan town where I grew up. My mother took me to the closest music store, which sold more PA and DJ equipment than musical instruments. They didn't have much in the way of guitars or basses, but I did leave with a copy of the March 1994 Bass Player magazine.

Inside, there was a feature story on Bob Babbitt. It recounted his entire career: playing on many hits as a member of The Funk Brothers, the Motown label's house rhythm section, and for other Detroit labels; then a move to New Jersey, which started a busy decade of session work in New York and Philadelphia, with more hits, more classic recordings; in the 1980s, a move to Nashville and more recording and touring. I found it really inspiring. This one guy had been in recording studios for decades working on great records, including some of my favorite music. Before reading this, I didn't even know that you could do that as a job.

Just before I moved from Detroit to Nashville in 2002 to find work as a bass player, I contacted Bob Babbitt through his website. He was very nice and suggested that I call him during my visit, which I did. We ended up meeting for lunch, and he told me really great stories about his time in Detroit, New York and Philly. And he passed along some valuable professional advice:

• Always be on time, be prepared and wear clean clothes.

• No drinking or drug use while working. He was very adamant about this, and said he'd seen it ruin a lot of lives and careers.

• If you're on the road and get called for a session, just say you're booked. They don't have to know where you are. "You could be in China for all they know!" he yelled.

After lunch, we hung out at his place and I got to check out his basses, including The Bass — the late-'60s sunburst Fender Precision that he played on hit records such as "Signed, Sealed, Delivered I'm Yours," "Inner City Blues," "Band of Gold," "Midnight Train to Georgia" and a whole lot more.

Bob was much more kind and humble than he had to be, and to a young bass player he barely knew. After his death, the outpouring of support locally and around the world proved that experiences like mine weren't uncommon. As impressive as his professional accomplishments were, his generosity made a lasting impression as well.

PERRY BAGGS

1962-2012

Drummer, Jason and the Scorchers; singer; songwriter; former Tennessean archivist

By Jason Ringenberg

Perry Baggs left us this year after a long series of illnesses involving diabetes. He came down with the disease in 1989, and somehow managed to rock all those stages with Jason and the Scorchers through the '90s and into the new millennium. Looking back on all that, I have to consider it one of the most impressive stories I have seen in the performance world. Even with those terrible health issues, he attacked the drums with a power equal to any 18-year-old. He never failed to give it his best.

Perry was a West Nashville native. As the Scorchers' drummer, he defined and owned the elusive drum spot where real rock 'n' roll and authentic country music meet. No one did that better, and I doubt anyone ever will. You knew it when Perry was playing. He had an instantly identifiable style.

He also was a brilliant harmony singer and naturally gifted musician. He grew up in the church singing gospel music, and his love for that never left him, to the end of his life. He had a beautiful voice filled with soul and personality. He had the rare ability to make whoever he was singing with actually sound bigger and better. He could match the lead vocal with uncanny accuracy. He could play guitar, bass, trumpet and piano. He didn't play music: He was music.

Within all that talent beat the heart of a true songwriter. Perry co-wrote many of our signature songs, such as "White Lies," "If Money Talks" and "Victory Road." My favorite of his was "Somewhere Within." To this day it never ceases to move me. I will never forget him singing the chorus to me while driving down a 4 a.m. highway in rural Texas. He also recorded many wonderful solo songs from his post-Scorcher efforts. I hope they someday see the light of day.

Perry is survived by a daughter, Faith Baggs, who inherited his grace and charm. He also leaves behind legions of friends, fans and colleagues who will remember his spirit and work. Every time I sing "White Lies" I will hear that voice singing with me.

ROLAND GRESHAM SR.

1934-2012

Guitarist

By Annie Sellick

Thank you, Mr. Gresham, for igniting me with jazz when I was 22 and hanging out in bars.

For a decade, Sunday night with the Roland Gresham Trio was a ritual for many who wandered in and out of The Boro Bar and Grill in Murfreesboro. On that night each week, candlelight diffused the harsh neon and confusing barrage of band bumper stickers decorating the venue walls. There was jazz, new for many of us, and Roland served it up on guitar with rough-edged sophistication.

He sang us "The Ugly Woman Song," laughing as he shot out a beaming smile. He strummed and soloed with his thumb, and wore plaid polyester pants. He dressed "The Girl From Ipanema" in Wes Montgomery guitar stylings. Gresham's ham-it-up personality, bluesy-side-of-jazz repertoire and melodic solos made the genre accessible and compelling to newbies. It was loud and it was loose, but it cooked.

In the 1960s, Roland moved in Nashville blues circles where the likes of Etta James and Jimi Hendrix made his acquaintance. Through the following decades he would remain in Middle Tennessee, trading blues for jazz and thereafter preaching its gospel, hanging out with Jack Pearson, Larry Pinkerton or Chet Atkins, playing in restaurant bars and teaching from back rooms in music shops. He simply loved to play, and would often do it just for tips in the most unlikely places — a billiard and bowling room, a Rutherford County sports bar, a college dive. A two-or-three-set job might become a five-hour affair where happy fans stomped the hardwood floor in an upstairs room on a small-town square. Fame and money meant nothing to him.

Rumor has it Roland declined a Ray Charles tour. Maybe it was because he wouldn't play on Saturdays.

At some point, he became a devout Seventh-Day Adventist and rejected the mainstream. Self-made and God-reliant, he built his own house and kept a strict vegetarian diet of food from his own garden. He didn't believe in doctors. Fit as an ox until developing lung cancer, Roland jogged to break a fever or chomped a handful of raw cashews, raisins and pearl onions to battle stomach problems — then he would throw his guitar in the car and go play.

His simple ways kept him local and available to us. He loved us back by letting us jam with him and taste old-school improvisation. He hired some of us and changed the courses of our lives. He remembered everybody's name.

Toward the end of his life, Roland lamented his involvement with secular music. But many of us first noticed jazz because of the charisma and passion he infused it with.

Which came first — our love for Roland or love for his music? They were one and the same.

RICHARD FARRELL MORRIS

1938-2012

Percussionist; visual artist

By Mark Edwards

Have you ever known someone who made the word "creative" seem totally inadequate? For me, that person was Farrell Morris.

Farrell was an insanely talented and versatile percussionist: In addition to his stint with the Nashville Symphony, he recorded or performed with the likes of Dan Fogelberg, Kris Kristofferson, Johnny Cash, J.J. Cale, George Jones, Kenny Chesney and Dolly Parton, to name a few.

When illness forced Farrell to give up his music career, he just shifted creative gears and moved seamlessly into the art world. Painting, sculpture, he was able to do it all. And he did it with the same passion and whimsy that was so overwhelming in his music.

Farrell's collection of percussion instruments was legendary. He had cases of objects he could play, from all over the world. If he heard a sound in his head that he wanted to use on a record session, he would reach into one of those cases and grab something. If he couldn't find the right instrument, no matter — he would just build something that would make that sound. It could be frightening and exhilarating at the same time to see that level of inspiration coming out of one person.

I knew Farrell for almost 40 years. One incident exemplified his creativity for me. While it may seem like a tiny thing, I've never forgotten it. In the early to mid-1970s, there was a band in Nashville made up of local studio musicians that went by the name "2002." Farrell was the percussionist. Their music was pretty indescribable, but it was mostly a jazz band. The tunes could be anywhere from three to 20 minutes long. One night at a gig, Farrell did one of the most amazing things I've ever seen: He cut a plastic milk jug in half and filled the bottom half with water. Then he took a cowbell and proceeded to strike it with a small metal mallet as he moved it up and down in the water, changing its pitch. It was the damnedest jazz solo I've ever heard.

Farrell pretty much owned Table 2 at the Nashville Jazz Workshop's Jazz Cave. He and his lovely wife Bobbie always sat at that table when they attended a concert at the workshop. I was fortunate enough to join them on many occasions. Farrell always made the event special, either through his musical knowledge or his razor-sharp sense of humor. I've not been able to sit at that table since Farrell passed away. There will always be something missing.

Farrell was a good friend and an amazing person, and I will miss him terribly.

SUSANNA CLARK

1939-2012

Singer; songwriter

By Edd Hurt

Susanna Clark came to Nashville in the early 1970s with her husband, Guy Clark, and both began writing songs that pushed country music's boundaries.

Around this time, as Nashville lore has it, the likes of Mickey Newbury, Larry Jon Wilson, Townes Van Zandt and many others gathered at her home to try out their new material. Energized by this hothouse atmosphere, she began writing songs.

Born in Atlanta, Texas, in 1939, Susanna Clark met Guy Clark in the late '60s, and the couple moved to Nashville in 1971. Married the following year on the houseboat of fellow songwriter Mickey Newbury, the couple began writing and recording.

Hitting with "I'll Be Your San Antone Rose" — a 1975 hit for country singer Dottsy — Susanna Clark went on to write songs that were covered by Rosanne Cash, Emmylou Harris and Miranda Lambert. With Richard Leigh, Clark wrote "Come From the Heart," a 1989 hit for Kathy Mattea.

A former art teacher, Susanna Clark used her training profitably, creating album-cover art for Willie Nelson's 1978 Stardust and Guy Clark's Old No. 1. With Carlene Carter, Susanna Clark wrote "Easy From Now On," which Carter recorded on her 1990 full-length I Fell in Love. The song later appeared on Lambert's 2007 full-length Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. "Easy From Now On" is your typical piece of genius songwriting, right down to the way Carter and Clark tease you with the song's title hook, which takes its time making its appearance.

In poor health in recent years, Susanna Clark died in Nashville on June 27. The songs and the art she created will endure, and will serve as reminders of that glorious, life-affirming period in which Nashville songwriters created the Texas-Tennessee hybrid that artfully balanced sentimentality and realism, and looked back over its shoulder at those wonderful 10-cent towns.

BRAD BAKER

1954-2012

Songwriter; sound engineer, The End

By D. Patrick Rodgers

Generously proportioned, unapologetically vociferous, and easily one of the finest sound guys in Music City, Brad Baker was known to playfully mock the bands that showed up to play The End, sometimes even critiquing them on mic or contributing unasked-for background vocals right in the middle of their set. Seriously. Into a microphone, right in the middle of the set. He'd bark orders at bands as they set up and tore down, or he'd recline out front in his pickup, eating a Styrofoam tray full of to-go food and hollering a jocular greeting at anyone who passed him by.

Baker — known to some as "Porque," pronounced "Porky" — was for many years shrouded in mystery and in local legend. He served as a touring technician for bands including REO Speedwagon, Journey, Loverboy and Prince; that part's definitely true. Appropriately enough, Baker — known for his hard-partying rock 'n' roll lifestyle — penned the tune "Wasted Rock Ranger," which proved to be pretty successful for Great White; that part's true as well. But the bit that we End-frequenting rock fans often heard and never quite believed was that he also wrote Guns N' Roses' "Night Train." Fairly certain that one's not entirely accurate.

But it wasn't just the dubious rock 'n' roll anecdotes that Baker was known for. In addition to being a genuinely talented sound engineer — honestly, the juxtaposition of Baker's pristine front-of-house mixes against the charmingly junky atmosphere of The End was a sound to behold — he was a surprisingly giving and likable figure beneath his playfully antagonistic exterior. As noted by local concert promoter and sound guy Jesse Baker (no relation) in his obituary from our Sept. 13 issue, "[Baker] even did insanely generous things like buying my groceries and helping with car trouble costs on a consistent basis. There are a couple years there that I definitely owe my comfort and sanity to Brad's generosity. And it wasn't just me."

Baker had a devil-may-care sensibility and a big appetite for life, and in recent years, health issues landed him in the hospital for stretches at a time. He was in his extended-stay hotel room in the Super 8 on Spence Lane when he died on Aug. 31 at the age of 58. Gone with him is not only some of the best sound mixing any local club could ever hope for, but also a stentorian voice and a surly exterior, and the great big heart underneath.

KITTY WELLS

1919-2012

Country music legend

By Jewly Hight

When a queen dies, a nation stops to grieve. For country music, the passing of Queen Kitty Wells was no less an event.

So far removed are we from the postwar early 1950s — and so used to the presence of formidable female voices in the country landscape — that it's hard to fathom a time when there were none to hear, outside of family groups. Wells was the first true country superstar who was also a woman, and the song for which she's best remembered, "It Wasn't God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels," was the first recording by a solo female singer ever to top the country charts.

A Nashville native, she wasn't actually born Kitty Wells — a name borrowed from a folk ballad — but Ellen Muriel Deason, into a family that sang purely for enjoyment. An aspiring country singer by the name of Johnnie Wright met the Deasons through his sister, who'd moved in next door to them. Soon enough, he and Wells embarked on a 74-year partnership in marriage and music that ended only with his passing in 2011. For the first several years, they primarily placed their hopes in the musical fortunes of Johnnie and Jack, Wright's duo with Jack Anglin. Besides filling the supporting role of the duo's "girl singer," Wells cut a few gospel sides for RCA, which went nowhere.

By her early 30s, Wells was ready to wash her hands of singing and focus on raising the couple's children. That's when Wright, at the Ernest Tubb Record Shop's Midnite Jamboree, was approached by a Decca A&R man who pitched him a song for Wells. She agreed to record "It Wasn't God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels" — an answer song to Hank Thompson's hit "The Wild Side of Life" — but only so that she could earn the session fee. Before she knew it, the song was a runaway 1952 hit, the first of more than 30 Top 10s she'd chart into the '60s.

This wasn't only the story of an individual artist's success — this was Wells proving, once and for all, that a woman country performer could hold her own, sell records and headline shows, matters about which plenty of people in the music business had had their doubts.

Though "feminist" is a descriptor that people frequently attached to Wells' big hit in our time, it's not an identity she ever claimed for herself. She deserves to be confronted in her admirable complexity: a woman speaking to the realities of her time with unadorned delivery, no-nonsense emotional intelligence and a gift for empathizing with people and stories that lay beyond her own experience.

It's a marvelous thing that Wells lived to see her induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1976 and the museum exhibit of which she was the subject in 2008. In the case of the latter, she was the first female country act to be so honored. Many musical generations of women have followed in her footsteps since the early '50s. If today, general knowledge of her music tends to be limited to her blockbuster breakthrough song, it may be because her influence is so foundational that it's ceased to be consciously recognized. People have forgotten the solid rock on which so much has been built.

BOB WELCH

1946-2012

Singer; songwriter; guitarist, Fleetwood Mac

By Edd Hurt

A skillful guitarist who became famous by joining the British blues band Fleetwood Mac, Bob Welch helped to steer the band, and thus '70s rock, toward a future that commercialized the blues of Elmore James by adding generous helpings of easy-rolling pop.

Born in Los Angeles in 1945 into a show-business family, Welch kicked around America before heading to Paris, and got his break with Fleetwood Mac after he had played in a succession of unsuccessful groups. By the time Welch was hired in 1971 to play rhythm guitar behind lead guitarist Danny Kirwan, the group was seeking a larger audience. Along with fellow new hire Christine McVie, Welch took Fleetwood Mac in a pop direction.

The track that pointed the way toward rock's future was Welch's "Sentimental Lady," which first appeared on Fleetwood Mac's 1972 Bare Trees full-length before Welch re-recorded it for his 1977 solo record, French Kiss. "We live in a time when paintings have no color / Words don't rhyme," Welch sings. As hit song and pop confection, "Sentimental Lady" throws over Memphis Minnie for one of those idealized L.A. ladies who populate the tunes of the Eagles, Firefall and the other American bands with whom Fleetwood Mac competed on '70s radio playlists.

Welch stayed with Fleetwood Mac through 1974, and afterwards the group went on to its greatest success with Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks. In 1978, Welch took "Ebony Eyes" to No. 14 on the U.S. charts, while "Hot Love, Cold World" made No. 31. The hits dried up after that, but he had a good ride. Welch was a master, and such giants should make their statements and then fade away to a life of sentimental ladies and easy times.

In later years, Welch was left out of Fleetwood Mac's lineup when the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. He moved to Nashville and released re-recorded versions of his signature songs, along with a jazz record. Concerned about his health — he had undergone spinal surgery a few months previously, and doctors had told him he was facing life as an invalid — Welch ended his life on June 7 with a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

MICHAEL GODSEY

1964-2012

Musician, Committee for Public Safety and Raging Fire; photographer; artist

By Michael McCall

Citing Michael Godsey's talents — musician, photographer, producer, visual artist, writer — suggests what a restlessly creative spirit he had. But a list doesn't convey how powerfully he had inspired those he befriended, collaborated with and mentored over his 47 years.

Everyone who spoke at Godsey's memorial service in May recalled how his encouraging words about art and expression — always one-on-one and intensely personal — changed their lives in profound ways. He didn't advise them on how to become successful artists; he pushed them to express something distinct from within themselves.

That's the Michael Godsey his Nashville friends knew and continue to love.

Growing up in Nashville, Godsey was a founding member of Music City's punk scene. As guitarist in the band CPS — the Committee for Public Safety — he was among the teen upstarts who transformed a downtown beer hall, Phrank 'n' Steins, into the city's first underground punk venue in the early 1980s.

Godsey made his greatest musical mark in Raging Fire, where he and vocalist Melora Zaner, a Vanderbilt student from Texas, created a punk-influenced sound distinct from any other in the Nashville scene. Drawing on The Who, the Beatles and such art-punk bands as X, Godsey and Zaner co-composed songs that were sensual and literate, yet at times exploded with rage, like Flannery O'Connor teaming with Tom Verlaine and Pete Townshend.

Godsey's guitar didn't fit with the city's Southern-fried roots bands, power popsters and heavy metal firebrands. His slashing style created shards of glass, combining dart-tipped melodic notes with crashing, dramatic chords.

Godsey and Zaner eventually wed and moved to New York City, where Godsey attended the Parsons School of Design. Then it was on to Seattle, where Zaner began a career as a pioneering international leader in designing software, for which she holds several patents.

Seven years ago, Microsoft moved Zaner into a top executive position in China. Godsey, with Zaner's assistance, built a home recording studio in Shanghai, and the couple mentored an ever-widening collection of young Chinese acolytes. The two formed Popnami Records as a joint partnership, and they co-wrote and co-produced an initial series of singles for Chinese rockers. Godsey also helped produce the 2012 recording debut of RA-6600, a Nashville rock duo featuring Mark Medley, Raging Fire's drummer and Godsey's friend since childhood.

That Godsey died amid a creative outburst fit his life. He had dealt with a heart condition throughout adulthood, but it didn't stop that heart from being as big as the world he had traveled. His heart continues to pulse today through all those he inspired over the years.

DOUG DILLARD

1937-2012

Banjo player; TV hillbilly; country rock pioneer

By Randy Fox

Doug Dillard's life changed the moment he heard Earl Scruggs' banjo playing on the radio. As he told the story, Dillard was 15 and driving the family's truck down a Missouri country road when the sound of Scruggs' three-fingered picking hit him like a lightning bolt, causing him to run the truck into a ditch.

Though the accident left no injuries, the sonic cause of the mishap was branded upon his psyche. Born into a musical family, Doug Dillard and his younger brother Rodney began their musical apprenticeship on guitar at an early age, but Doug's roadside banjo revelation pointed him in a different direction.

By 1962, with their band The Dillards, the brothers were ready to shoot for the big time. But in a move that seemed to defy all logic for a bluegrass band, they headed for the hills of L.A. instead of Nashville. They found a home in the flourishing West Coast folk scene and soon signed with one of the premiere folk-music labels, Elektra Records. They also found themselves in the role of bluegrass ambassadors to the nation when they landed a spot portraying the musical family "The Darlings" on The Andy Griffith Show.

But if the fictional Darlings were supposed to represent Hollywood's idea of traditional mountain music, The Dillards' recordings painted a different picture. The Dillards became one of the first bluegrass bands to push the limits of the genre — adopting electric instruments, adding drums and other non-traditional elements. In 1967, Doug left the Dillards to work on solo material and collaborate with The Byrds founder Gene Clark on two groundbreaking albums that helped give birth to the country-rock movement.

For the next 40 years, Doug Dillard continued to work on his own projects while collaborating with others, building his reputation as a skilled and innovative banjo player. He was also known for the wide and friendly smile he always wore onstage. It came from the satisfaction of having mastered the magic sound that inspired his reckless driving all those years ago.

Music Remembered

Willie Ackerman, 73, drummer for Loretta Lynn and others, a staff drummer for the Grand Ole Opry and the TV series Hee Haw.

Larry Butler, 69, producer of Kenny Rogers' career-topping albums including 1978's The Gambler; only Music Row producer to win the Grammy for Producer of the Year.

Levon Helm, 71, drummer, mandolin player and vocalist for The Band, actor and de facto godfather of the Americana movement.

Margaret Ann Buxkamper, 66, one of Nashville's first female sound engineers; particularly noted for work with Nashville Children's Theatre, TPAC and Opryland.

Al DeLory, 82, producer-arranger on Glen Campbell's greatest hits, including "By the Time I Get to Phoenix," "Wichita Lineman" and "Galveston"; part of renowned L.A. session team known as the "Wrecking Crew"; played keyboards on the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds; for many years fronted the Nashville Latin ensemble Salsa en Nashville.

Frank Dycus, 72, veteran songwriter whose more than 500 songs include George Jones' 1992 smash "I Don't Need Your Rockin' Chair."

Tim Johnson, 52, prolific songwriter whose hits included Jimmy Wayne's "Do You Believe Me Now" and Kellie Pickler's "Things That Never Cross a Man's Mind"; co-founder of The Song Trust with Joey + Rory's Rory Lee Feek.

Rita Lee, 73, co-founder with husband Buddy Lee of Nashville booking agency Buddy Lee Attractions; born Yolanda Gutierrez, later pioneering female pro wrestler under the name "Rita Cortez, the Mexican Spitfire."

Kenny Roberts, 85, known as "America's King of the Yodelers" for hits such as 1949's "I Never See Maggie Alone."

Joe South, 72, pop star, producer, songwriter and session great whose 1969 Song of the Year "Games People Play" remains a standard.

Doc Watson, 89, legendary musician. "I have seen the David, I've seen the Mona Lisa too / I have heard Doc Watson play 'Columbus Stockade Blues.' " —Guy Clark, "Dublin Blues"

[page]

BUSINESS

FRANCES WILLIAMS PRESTON

1928-2012

Former president, BMI

By Kay West

For a good part of her illustrious six-decade career — virtually all of it with performance-rights organization BMI — Frances Preston was referred to as "the most powerful woman in the Nashville music industry." In 1986, when she moved from Nashville to New York and assumed the presidency of the entire company, she became "the most powerful woman in the music industry," a title she held until her retirement in 2004.

But for Music Row and the community outside its borders — two worlds she worked hard to bring together — what Frances Preston may be most fondly remembered for is not her power but her hospitality.

Whether it was the conference room at the original one-story BMI building on Music Square East that was open to any group who reserved it (and found it prepared with hot coffee, cold drinks, cookies, fruit, china, crystal and silver) or a cocktail party at her beautiful home on Woodmont Boulevard, Preston imbued every gathering with her exquisite taste and impeccable manners, cloaked in genuine warmth.

But it was the BMI Country Awards dinner that set a new standard for entertaining on Music Row and changed the perception of the country music industry in Nashville and on both coasts. All the writers, publishers and guests who have been feted so spectacularly since have Frances Preston to thank.

For the five years prior to her being tapped to open the first BMI office in Nashville in 1958, hit songs were recognized as part of the annual fall WSM DJ Festival and Grand Ole Opry celebration. In her first year as BMI's sole Nashville employee, Preston suggested shining the spotlight on the writers of those songs, and staged a breakfast in the downtown Maxwell House Hotel to honor — among others — BMI writers Mel Tillis, Johnny Cash, Buck Owens, Don Everly, Ferlin Husky, George Jones, Harlan Howard and Roger Miller.

It was a huge hit, and the next year, she transformed the event into a black-tie dinner at the Belle Meade Country Club. In addition to honorees and industry members, Preston also invited leaders of the business, arts, academic, political and philanthropic communities, knowing that for the music business to gain respect and grow, it had to dress up a little and reach out beyond Music Row.

The dinner remained at BMCC for 17 years, until some club members complained about the presence of emerging African-American writers and artists — Charley Pride for one — crossing their color line and comfort zone. When Preston was told she would have to uninvite them, she moved her dinner to the BMI office parking lot, where it became the most glamorous party ever held under a tent. Every year from 1976 through 1993 (with one temporary move to TPAC), Preston and her second-in-command stood at the entrance to the tent, personally greeting and snapping a photo with every single guest. She changed gowns between cocktails and trips to the stage, where she emceed the affair and distributed awards.

Even after she moved to New York, she returned to Nashville every fall for the dinner, one of her favorite nights of the year. In 1994, when the new BMI building was being constructed, the dinner was held at Municipal Auditorium, then returned in 1995 to the top floor of the parking garage with a spectacular view of the Nashville skyline.

In 2005, Del Bryant — son of "Rocky Top" composers Felice and Boudleaux — who had succeeded the woman who hired him decades before, took over as host, and Preston segued gracefully to a guest at the dinner she created. On Oct. 30, she was remembered from the stage of the 60th annual BMI Country Awards. Once the most powerful woman on Music Row, she will remain the most unforgettable.

DONNA HILLEY

1941-2012

Music industry executive

By Kay West

Donna Hilley, a Birmingham, Ala., native who moved to Nashville after graduating from Jones Valley High School in 1958, began her climb to the top of the music industry at ground level. Her entry point was the front desk at WKDA radio station. In 1978, she was named executive vice president and chief operating officer of Tree International, one of Music Row's top publishers.

Her story wasn't dissimilar to the other female leaders of the day — BMI's Frances Preston among them — who started as receptionists or secretaries, then seized every opportunity that presented itself, took on any task, no matter how mundane, and parlayed larger-than-life personalities, drive, hard work and a very Southern style of leadership to the executive suite.

During her tenure at Tree, Hilley negotiated the company's acquisition of more than 60 major catalogs, including those of Jim Reeves, Conway Twitty, Buck Owens and Merle Haggard, and Tree's sale to Sony in 1989, where she assumed the role of president and CEO in 1994. In 2002, she orchestrated Sony/ATV's acquisition of Acuff-Rose Music Publishing.

At BMI's annual fall awards dinners, Hilley made countless trips to the stage to retrieve plaques for her company. Looking back, Preston once remarked, "Tree was Publisher of the Year so many years it got to be embarrassing. Donna kept buying companies and she kept up with them all too. She'd call me all through the year, wanting to know how many performances so-and-so had!"

Though Preston and Hilley were not personally close, they moved in the same social circles, were friendly, and held each other's professional accomplishments in high regard. They also shared, like many women of that era, a propensity to fudge about their age.

When Preston passed away on June 13, 2012, it was discovered that the birth date on her bronze plaque in the Country Music Hall of Fame — Aug. 27, 1934 — was incorrect; she was actually born on Aug. 27, 1928. Similarly, when Hilley died June 20, 2012, some obituaries printed her age as 65, while others got it right at 71. Both women shaved six years — and got away with it until their deaths.

On Oct. 10, Donna Jean Hilley posthumously received the Frances Williams Preston Mentor Award from the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame Foundation.

JOHN DEAN

1946-2012

Restaurateur

By Dana Kopp Franklin

It's hard to overestimate how important McCabe Pub has been to the transformation of the Sylvan Park neighborhood over the past 30 years.

When John Dean and his wife Josephine opened the pub on Murphy Road in 1982, Sylvan Park was a fairly obscure little corner of West Nashville, not the hot sector of real estate it would become. Dean, who died in January at age 65, made quite a mark there.

Much more than a typical sports bar, McCabe has been an anchor of the neighborhood, with a strong core of local customers plus folks from other parts of town attracted by McCabe's diverse menu of burgers, Southern cuisine, daily soups and specials, grilled fish and desserts.

Sylvan Park residents, of course, were the first to discover the pub. (Now the neighborhood clientele encompasses three generations.) The bar at McCabe became a place of civic discourse and lively debate, and Dean always chimed in with his own strong viewpoint.

Though opinionated and sometimes prickly, Dean attracted devoted friends and had a multitude of interests. He loved West Nashville (he was a native, who graduated from Cohn High before attending MTSU, Belmont and UT), but he also loved global travel and opened a hotel in Nepal in 1999.

McCabe Pub continues to thrive with Dean's daughters at the helm. Whether diners stop by for a daily Southern special or a fresh slice of pie, a cocktail on the patio or a good debate at the bar, they're enjoying the legacy of John Dean.

MICHAEL KINNARD PONTES

1968-2012

Restaurateur

By Kay West

Michael Pontes saw Jimi Hendrix perform when he was just 2 years old, in the company of his mother Jackie, a free-spirited flower child. Single, she carried her child with her to concerts and communes before settling — kind of — in a meadow at the end of a two-mile road that wound between two mountains, in a holler outside Floyd, Va. It was the kind of place where people lived off the land, unfettered by convention and the scrutiny of the law.

It was there Pontes first learned to fend for himself, a skill that came in handy throughout his life. With a natural gift for running the rigorous trails around him, he pursued cross-country, made his high school team and, longing for structure, moved in first with his coach, then the family of his buddy Jeff. He got an invite from Clemson, but representatives of Brooks running shoes steered him to Belmont, a scholarship he accepted.

That's how he came to cross paths with Neal & Harwell attorney Bill Ramsey, a couple of decades his senior and a world removed from Pontes'. At the time, guitarist John Jackson was renting the top-floor apartment of Ramsey's Belmont-area home; he came to his landlord and asked if his new friend Pontes could move in as well. "He was 18 or 19, and a little-bitty guy, no more than 5-foot-4," Ramsey remembers. "That first year, he grew six inches."

He ran cross-country all four years at Belmont, setting a record that stands to this day on Percy Warner's horse trail: 8.3 miles in 42 minutes. After graduating with honors with a degree in marketing, he tried on many hats — the music business, working closely with BR549 in their Robert's days, bartending at Pub of Love, and construction, fine-tuning his carpentry skills under the tutelage of expert craftsmen. It was during that era, Ramsey remembers, that he got into some trouble with substance abuse and financial issues.

"Mike had his demons, and he probably had some kind of emotional disorder, his highs were so high and his lows so low," Ramsey recalls. "He would self-medicate, because that's the culture he grew up in. But he was gritty and fearless, and he always bounced back."

Part of his bounce-back lay in his affinity for hard work — whether training for cross-country to the point of injury, or in physical labor. Pontes built the side addition to the cafe Frothy Monkey in 12South, crafted all the tables and chairs and bar for Burger Up a few blocks away when it opened in 2010, then did the build-out and furnishings for the Burger Up in Cool Springs, which he also ran.

The Rev. Becca Stevens, his friend and pastor at St. Augustine Episcopal Church, believes he found grace in hard work. "Mike did so much for the St. A's community, but he was not a committee-meeting guy," she says. "He was the guy who cut the wood and hammered the nail. He was happiest when he was in labor, in motion." The final labor Pontes performed for St. A's was to hand-chisel the tiny cedar plugs for the new pews he helped make for the chapel, lasting talismans to his memory.

Michael Pontes could run like the wind, but ultimately, he could not outrun the demons that haunted him. Blessedly, he could not outrun his friends either, hundreds of whom gathered under a tent on Cal Turner's farm on a bleak March afternoon to hear Stevens' prayer for Michael; anguished words from his mother and old friends; heart-wrenching performances from Bobby Bare Jr., Etta Britt and John Jackson; and to sing together "You Are My Sunshine." Magically, the heavy gray clouds roiling across the sky were pierced for a sweet moment by sunbeams.

Four days later, Ramsey, Jackie and other intimates went to Ramsey's family farm in Viola, a place where Pontes often turned for rest and respite. They put half of his ashes around an October Glory maple tree planted in his honor, and the rest on the trail he made there, which he loved to run.

KEVIN MOSER

1967-2012

Hair stylist to the socialites; owner, Element Salon

By Abby White

Loyal. Loving. Generous. Kind. Open. Honest. Ask anyone who knew Kevin Moser, and these words come up repeatedly. To the outside world, he is best known as a successful salon owner and stylist to the Nashville social set — he was the go-to guy for Swan Ball hairstyles. But to his friends and family, he was so much more. Moser, who passed away from natural causes on June 28, 2012, at age 44, was a stranger to no one.

"Kevin was the type of person that, whether he was greeting you for the first time or not, he made you feel like he cared about you and loved you," recalls Moser's partner, Scott Stalker. "He was generous and kind with his whole being."

Born in Jacksonville, Fla., and raised in Chattanooga, Virginia Beach and Crossville, Tenn., Moser attended MTSU before moving to Nashville in 1996, where he learned his craft at Jon Nave University of Cosmetology. Moser, uniquely gifted with both creativity and entrepreneurial spirit, opened his first salon in the upscale boutique Jamie. He opened the luxurious yet welcoming Element Salon in Green Hills in 2000, allowing many employees to flourish under his instruction.

"He was more than my best friend — we were family," says Christy Gibson, a friend of Moser's for 20 years. Moser and Gibson were big Madonna fans, and they attended several Madonna concerts together. She recalls the first, years ago in Atlanta. "Right before the show started, he grabbed my hand and said, 'I think I'm going to cry when she walks out onstage,' " Gibson says. "We both did. We danced and sang for the entire show, even though we were in the nosebleed section and were nervous about falling over the rails."

Gibson was among a group of Moser's close friends who scattered his ashes at a Madonna concert in New Orleans in October.

"Everyone knew Kevin," Gibson says, fondly remembering her friend. "No last name needed." Like Madonna.

JAY LUTHER

1965-2012

Cook, restaurateur

By Kay West

Despite the fact that he ran the kitchens at Germantown Café and Allium — the restaurants he opened and owned with Chris Lowry, in 2003 and late 2008 respectively — Walter Johnson "Jay" Luther preferred to be called "cook" over the more formal "chef." When asked once by an impressed Germantown Café diner where the chef had attended culinary school, general manager Greg Hilbourn only half-jokingly replied, "The Norma Luther Cooking Academy." Jay Luther did learn many lessons from mother Norma growing up in Dickson, Tenn., but the menus at both restaurants were unmistakably his. For the most part, they remain so, though longtime colleague and veteran Germantown chef Jeff Martin is now the one cooking them.

"Jay's menu, by design, was not complicated or fussy," says Lowry, who was also Luther's life partner of 18 years, a relationship that began when they both were servers at the old Granite Falls. "We have updated the menu and Jeff has added several new things, but Jay created some perfect dishes that people love and would be upset to see removed, and we have no reason to do so. Jeff was trained by Jay, and he cooks them faithfully. " Luther's signature comfort dishes — French onion soup, Germantown Strudel, squash fritters, plum pork, coconut curry salmon and braised lamb shank, for example — have become even more comforting in the wake of his passing, reassuring touchstones of his continued presence.

His desserts — which he most enjoyed making — are more problematic to re-create. "He liked to play a lot, but he also got a lot of the recipes for cakes and pies from his mother," Lowry says. "She always left an ingredient out, and it was fun for him to figure out what it was. She made a killer chess pie, and it took him forever to figure that one out. But he did, and his chess pie was as good as hers. Unfortunately, he never shared that one secret ingredient with us."

What he did share with the staff was his prankish sense of humor; a tireless, democratic work ethic; and an admonition he repeated so often it became a slogan. "Jay wasn't the kind of chef who liked to go out and walk through the dining room," Lowry says. "He was happiest in the kitchen. But if he looked up and saw too many servers hanging out there, he would say, 'Who's watching the door?' — which was the signal for them to get back out to the front of the house."

A framed photograph of Luther in the water of Curaçao from a 2010 vacation hangs on the wall behind the host stand at the entrance of Germantown Café. Lowry put it there not long after his friend and partner's death, a poignant answer to Luther's rhetorical question: "Who's watching the door?"

JOSEPH H. "TIGER JOE" THOMPSON JR.

1919-2012

Decorated pilot; businessman; former president, Nashville Rotary Club, Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce

By J.R. Lind

There are those for whom the name "Greatest Generation" seems singularly made. The men and women who won the Second World War created modern America: After bringing fascism low, they returned home and built a country. Joseph "Tiger Joe" Thompson — whose nickname ranks among the finest in the history of a city rife with outstanding sobriquets — was a shining example.

Flying with the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron and the 109th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron of the 9th Army Air Force, he helped liberate France from the Nazis. He received awards from two grateful nations — the Distinguished Flying Cross from his own, and the Croix de Guerre and Légion d'honneur from France. The Fifth Republic granted him the latter just days before he died in Nashville at 92.

After the war, he returned home, taking a job as an agent with Northwestern Mutual. He worked his way up to an executive position, staying with the company into his ninth decade. Later, he would serve as president of the Nashville Rotary and then as Chamber of Commerce president starting in 1979.

In 2006, he published Tiger Joe: A Photographic Diary of a World War II Aerial Reconnaissance Pilot, a book of photos from his time in the war. It wasn't the only way he passed down his memories. He was a treasured guest at Montgomery Bell Academy assemblies, where he shared his remembrances year after year with successive classes. He made America's finest hour come alive, not as a dry recitation of stats and dates, but as history seen in the moment in bursting skies, through an aviator's goggles.

Tiger Joe Thompson helped save the world, and he helped build his city, and he left a legacy for the rest of us. Greatest Generation, indeed.

MARIO FERRARI

1932-2012

Restaurateur

By Kay West

Mario Ferrari named his infamous party boat and his own farewell party late this summer La Dolce Vita, and that's what he lived: the good life. That's not to say we didn't have our differences. Many years ago, the Scene and Mario kept up a lively, litigious feud, and we battled royally over a critical review. But there are a million great stories about the grandiose, charismatic, flamboyant, self-invented restaurateur, even if some of the best ones cannot be verified or repeated in public.

"He was a legendary figure for over 40 years as the focal point of owner-operated restaurants," says Randy Rayburn, whose own empire includes Sunset Grill and Midtown Cafe. "No one else had that kind of staying power. Others stood on the stage, but none as long as him."

His path to Nashville began in poverty in Italy, according to Village Wines owner and restaurant-industry veteran Hoyt Hill. "He came from nothing, and knew he could have a better life in America," Hill says. "He was a stowaway on a freighter and when it docked in N.Y., he jumped ship and got a job as a dishwasher in a restaurant. He met a girl there who was an aspiring actress, and they moved to Hollywood. When she decided she wanted to be a country singer, they came to Nashville. I don't know how much of that is true, but it's the story he told me."

When he got to Nashville, he got a job bartending at the Executive Club. Because it was a private club, it was able to sell alcohol back in Music City's pre-liquor-by-the-drink days. He told Hill he saved his money, then borrowed $5,000 from a man in Memphis to open his restaurant Mario's in an old townhouse on West End Avenue.

"At the end of the first week, he had to borrow another $5,000 from the same guy," Hill remembers. "By the end of the third week, he paid him the $10,000 back in cash and was debt-free from then on."