Springsteen is blasting from a makeshift audio system in the brew house at Jackalope Brewing, because Springsteen is always playing in the brewery when Bailey Spaulding is making the beer. First it's "Brilliant Disguise," followed by a live version of "Atlantic City," and then "Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out."

Spaulding, Jackalope's CEO and brewmaster, turned a Harvard undergraduate degree and Vandy law degree into mornings like this — spent pushing grain out of one vat with a wooden oar and dropping hops into another to make a batch of Rompo Red Rye Ale, Jackalope's version of an Irish red beer.

Ask about her legal career, and Spaulding just laughs. Law school can be an awfully expensive way to figure out how much you want to turn a passion for home brewing into a career, but it's something she doesn't regret. Her legal license expired a year ago and she hasn't missed it at all.

Every enthusiastic home brewer has a moment when they think about ditching their day job and making beer for a living. Nashville's new wave of breweries is filled with former bankers and accountants, software writers and derivatives traders; to a person, they wouldn't trade their new profession — despite the pay cut and all the stress that comes with a startup — for their old one.

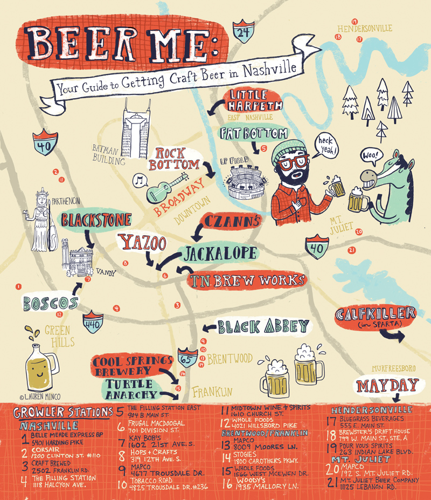

We are awash in new breweries, all part of a big second wave after Yazoo and Blackstone secured a beachhead for craft beer in the Nashville area a decade ago. All told, there are now 11 breweries in the area (with at least two more rumored in the works), and even more when you count the brewpubs.

Spaulding was hooked from the first time she made her own beer. She was a biology major at Harvard, so the mechanics of brewing — water and heat plus natural ingredients plus living cultures — made sense.

"I made a nut brown," she recalls. "I went to All Seasons and got the little Brewer's Best brewing kit and they had a nut brown recipe and I thought, 'That seems hard to mess up.' I was into darker beers, but now I don't discriminate. People are always like, 'What's your favorite beer,' and I really don't have one. But that nut brown came out and I was like — I want to do this, forever. I definitely don't want to be a lawyer."

It sure isn't glamorous. Spaulding's fingernail polish is chipped all to hell and the footwear is red rubber boots, always handy when a bad gasket leaks scalding hot wort — the early stage of beer before fermentation — onto your toes. There are kegs to wash and fill, all manner of cans and ingredients to schlep, and equipment to check (and fix). If you thought it was just about making something you can drink, think again.

Robyn Virball, Jackalope's president and Spaulding's best friend from college, puts it like this: "It's 90 percent about doing the dishes. If you don't like doing the dishes, don't do it."

"Come wash our kegs for a couple of days," Spaulding adds. "Come in July."

Inside the warehouse, where giant cookers turn water, grain and hops into beer, it's about 10 degrees hotter than outside.

People sweat a lot.

Jackalope’s Robyn Virball, Bailey Spaulding and Steve Wright

"Actually, just keep honing your craft, and if you really can't think about doing anything else, then that's what you should do," Spaulding continues. "I still can't think of anything I'd rather do than this. But if you can think of something else, you should probably do that."

The duo started the brewery in 2010 and found Nashville immediately receptive. By 2012, on a brewing system that makes only 15 barrels of beer at a time, they turned out 1,100 barrels of beer. That doubled in 2013, and now they're projecting 5,000 barrels of beer for 2015. To put that in perspective, that's a little more than 1.2 million pints of beer. They added Steve Wright as head brewer and COO three years ago, and have recently added two more assistant brewers to keep up with demand.

"That's a really good feeling," Spaulding says. "We hired people. We created something." And while she, Virball and Wright are very proud of the beer they make, there's a sense from talking to the group that they're enamored with the idea of making something of quality, something that is more permanent than the beer. It's a long way from just selling to the eight bars they started with.

Want to know where they're aiming? Look at their ceiling, which is plumbed for twice as many tanks as there are now. One of their other beers, Thunder Ann, an American pale ale, is slated for a monthly canning run — part of their strategy for hitting 5,000 barrels next year.

Every few weeks, a mobile canning company called Toucan (yes, there's a bird in the logo) rolls up to can 100 cases per hour. A microbrewery's growth is ultimately limited by distance and audience, and even if Jackalope could keep sending out more kegs to more places, reaching the beer drinker who doesn't go to bars or restaurants is the motherlode. That means packaging.

Adding a bottling line would be a huge capital expense — six figures at a minimum — so they became the first brewery in the area to use Toucan, a service based in Bowling Green, Ky.

"Canning was a pretty clear choice for us," Spaulding says. "We're totally unfiltered, so we need the most stable container possible. It's totally opaque, and there's less oxygen head space in there, so your beer stays fresher much longer because light can't get in there and skunk it."

Thunder Ann cans are available in a few grocery stores and beer outlets. Other breweries in the second wave will follow as soon as they're able. Turtle Anarchy, the Franklin-based brewery, just signed a lease for a 25,000-square-foot facility on Charlotte Avenue where they will brew and can their own beer as well as others. Brand-new breweries Black Abbey and Tennessee Brew Works both built their facilities with bottling lines in mind.

"There's so much room for growth in craft breweries in Nashville," Spaulding says, dropping hops into another batch of Rompo.

David isn't slaying Goliath anytime soon, but there is real optimism among craft beer makers nationally.

In 2013, the big national breweries — think Budweiser and Miller — were down 1.9 percent. Imports dropped 0.6 percent. Craft beer, meanwhile, grew by a staggering 17.2 percent. That growth comes from a relatively small base (15 million barrels vs. 196 million), but it's robust enough to have importers worried.

"In 2008, imports sold 20 million barrels more than craft (28.7 million vs 8.5 million). In 2013, that gap dropped to less than 12 million (27.5 vs 15.6 million barrels for craft)," according to Bart Watson, the chief economist at the Craft Brewers Association. "Given demographic changes and the rise in Mexican imports, I do expect imports to rise in coming years, but even with a rise in imports this year, craft has continued to close that gap."

That rise in Mexican imports is likely being fueled by the large marketing budgets at Heineken USA — "stay thirsty, my friend," their Dos Equis ads implore you — and Crown Imports, distributors of Corona and others. But even with all of those competing ad dollars, craft beer sales have nearly doubled in the past five years in the U.S.

Years ago, the big boys saw this trend coming. Multi-zillion-dollar advertising budgets, Bud Bowls and Silver Bullet trains on TV will only get so many beer drinkers to down watery swill marketed as "cold-filtered" and "brewed from Rocky Mountain springs." So they rolled out their own craft-inspired beers like Blue Moon and ShockTop while also acquiring regional brands like Chicago's Goose Island, which they began brewing in their own mega-plants.

"There are a number of challenges [for craft brewers]," Watson continues, "including regulatory barriers — particularly at the state level — competition from other beverage alcohol segments, distribution channels — there is only so much shelf space and there are only so many tap handles — and keeping quality high."

A good gauge for those tap handles in Nashville is Austin Ray's M.L. Rose Pubs, where both locations have shifted to exclusively serving craft beer on draft.

"The number of local taps has grown exponentially in the last three years," Ray says. "I think we had two or three Yazoo selections [when we opened]. And now, we regularly represent eight to 12 beers from six or more local breweries at any given time."

There are a number of reasons for this, from local pride to a shrewd analysis of what a particular beer drinker wants. Ray says it was kind of a "gut-check" when they got rid of their last non-craft tap, but it's paid off. Craft beer drinkers are more likely to have an affinity for places that serve it, spend more money and buy more food. A Budweiser or Coors drinker, on the other hand, probably isn't going to care whether or not it's in a bottle, can or on tap. They can't sell pitchers of Miller Lite, but then again, when your sign reads "M.L. Rose Craft Beer and Burgers," that market wasn't coming in the door anyway.

So what's moving at his place?

"We haven't been able to take off Black Abbey's Rose, because we're M.L. Rose," he says. "For some breweries, some of these beers are proving themselves to be super easy to like, and therefore are the most popular off the bat. Tennesee Brew Works Extra Easy Ale, Black Abbey's the Rose, Jackalope's Bearwalker Brown. We sell a whole lot of Dos Perros from Yazoo."

Ben Bredesen, who opened Fat Bottom Brewery in 2012, echoes Ray.

"One of the things I realized about this market is that people wanted things that weren't the crazy thing," Bredesen says. This isn't the West Coast, where an arms race of hops has flooded the market with ultra-bitter IPAs. Nashvillians wanted "something that they could drink a couple of beers that night and not be too over-the-top or too full or whatever. Something they could actually taste the food with what they were drinking."

Not coincidentally, his biggest seller is Ruby, an American red ale that isn't overly hopped. It accounts for 65 percent of all of Fat Bottom's sales, which are expected to reach 1,800 barrels this year. That already puts him above the mean of 1,706 barrels for U.S. microbreweries. While a smaller place like Nashville newcomer Czann's will make 200 barrels, Tennessee Brew Works and Black Abbey are expected to produce 2,000 barrels in their first full years.

Tennessee Brew Works' Christian Spears believes it's just beer catching up with other trends.

"There's a shift in the palate of the population," he says. "Go to a wedding 15 to 20 years ago, there was a lot of white zinfandel drinking going on. Now people are looking for a wine they recognize. They're looking for a vintage that's good. They're looking on menus for things, because they care. ... There's still a lot of trash beer drinking going on, but it's getting better. What happens is that their palates have evolved, and they don't necessarily regress. Wine has already gotten that appreciation, beer is just happening a little bit later."

Other breweries are flooding the local market with quality options: Little Harpeth has focused on lagers; Calfkiller's seasonal lineup includes beers like Wizard Sauce (a "magically hoppy little summer concoction"); Turtle Anarchy has gotten a lot of praise for its Portly Stout.

Craft beer options are exploding in Nashville.

"Shut up!" booms Carl Meier to an entire theater full of people who are there, in part, to sample his beer. It seems like a weird thing to tell your fans, especially when some are carrying swords.

"Ni! Ni! Ni!" the crowd responds.

Meier does a pretty good Graham Chapman voice, and the audience, at the Franklin Theater for a sold-out screening of Monty Python and the Holy Grail sponsored by the brewery, clearly gets a kick out of a couple of beer guys who named their summer seasonal after Brother Maynard, the character who orders a reading from the "Book of Armaments, Chapter 2, verses 9 through 21."

Black Abbey’s JOhn Owen and Carl Meier

Meier and his partners John Owen and Mike Edgeworth launched Black Abbey last year, leasing space for a Reformation Era-themed brewery and 72-seat "fellowship hall" on Sidco Drive. Their Belgian-inspired beers have been warmly received, quickly gaining taps in restaurants and bars around the city.

At the same time Black Abbey was coming together, the guys from Tennessee Brew Works were racing to open their own long-planned brewery and taproom. They launched last year in a warehouse near Third Man Records, where they've installed a gorgeous automated system with a unique filtering setup capable of kicking out 60,000 barrels of beer in a year. (They won't approach that for a long while, though.) It became a joke between the two breweries as they looked at the same real estate two years ago, crisscrossing the city in search of space with high-enough ceilings and enough square footage to build something for the long haul.

They even released their first beers — "Jude" from Black Abbey, "Opening Act" from Tennessee Brew Works — on the same day this past August. It's something neither could have done without the support and knowledge of other craft brewers. Yazoo's Linus Hall advised Black Abbey how to set up their drains, while Blackstone's Kent Taylor sent his maintenance manager to check in on them every few weeks during construction.

Over at Tennesseee Brew Works, Spears and his brewmaster, Garr Schwartz, got advice from all over, including established breweries that opened up their books for them to look at revenues. A distributor in North Carolina, for example, told them that the No. 1 problem with craft breweries is the supply of kegs.

Spears says they were told, " 'We're selling every drop of beer these brewers can produce — they can't deliver us the beer.' And they're going to end up losing taps because of it. The restaurants and bars want the beer, they're excited. But the breweries can't deliver and they get pissed off. They're losing accounts because of success. Think about that."

It would be very easy for the microbreweries to be suspicious of each other as they all fight over such a small piece of the pie. But for the most part, there's a convivial attitude that a rising tide lifts all craft breweries. Most of them are friendly, realizing that their competition is the multinational conglomerates, not each other. On a recent weekend day off, Meier and Jackalope's Wright even brewed together, concocting a beer they called "Left Behind" after Spaulding and Virball went to Denver for a brewer's conference and left Wright at home to run the shop. Meier and Wright rolled out the 10-gallon batch at Craft Brewed pub a few weeks later and it was gone in a half-hour.

"You have to see it to believe it. It's like, even if we didn't like each other," Spears says. "Think about the personalities that go into this field. We're all kind of like-minded, so we get along. But even if we didn't, even if we were just cold-hearted human beings, it makes no sense for us to be going at each other. People think we're making the same product, but we're not. Ninety-three percent of the beer world is still Budweiser and Miller-Coors. It's like fighting over a little mud puddle next to the ocean. It just happens to help that everyone's pretty cool."

Meier recently hooked up with a local interdenominational group that likes to drink beer and sing hymns, which seemed perfect for their Martin Luther-styled taproom. As he was about to have posters printed for the event, Meier realized that more than 400 people had responded to a Facebook invitation. Suddenly, Black Abbey needed to worry about crowd control more than publicity.

How powerful is the demand from a city with a thirst for craft beer? Meier sums it up best in one sentence: "I had to hire a bouncer for a hymn sing."

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.