Josef Newgarden

A Saturn IB rocket stands by the interstate halfway between Nashville and the Barber Motorsports Park near Birmingham, Ala., a pointy reminder that Alabama has a long history in aerospace technology and building vehicles that propel humans at high rates of speed. This has much in common with the activities at Barber on a recent April weekend.

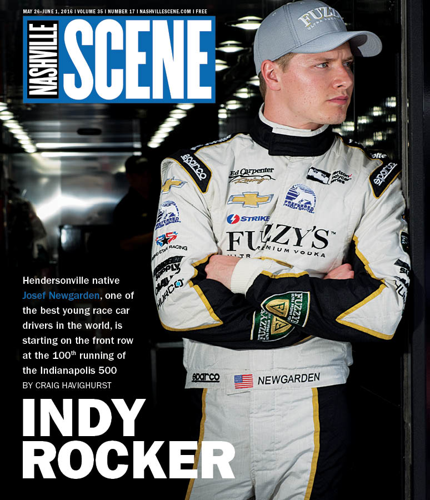

Josef Newgarden arrives at the race track on Thursday around lunch time. He's in a black team jersey and a mandatory Fuzzy's Vodka ball cap — sponsors are life to the series. The mobile headquarters of Ed Carpenter Racing, a thoroughly customized, high-tech semitrailer, sits in a row of similar vehicles, defining the weekend's temporary IndyCar paddock. Between the two dozen trucks, tents make temporary open-sided garages. In back of Newgarden's tent is a catering operation. In front, amid stacks of Firestone racing tires and surgically tidy tool carts, is another kind of rocket, in a semi-assembled state.

"When I was a kid, they looked like jet airplanes that drove on the ground," says Newgarden. He's all contained enthusiasm, part 25-year-old elite athlete and part go-kart-driving teenager, with bright blue eyes, dimples and a matinee-idol chin. "Which is why I loved them."

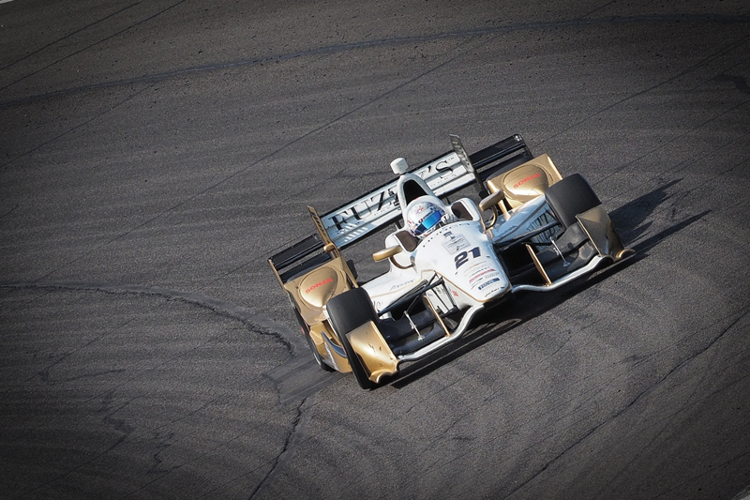

In race trim, Newgarden's car, No. 21, sports a handsome white-and-gold livery, but on this day of preparation, its carbon-fiber skin and elaborate wing structures are resting as detached parts on bespoke racks. Revealed are the hoses and wires of the car's respiratory, circulatory and nervous systems, clinging vine-like to a turbocharged V6 engine. With its tires off, the car looks like a robot insect sent through a wormhole to menace humanity.

"I watched NASCAR, sports cars, F1, IndyCars," says Newgarden, "and I always thought open-wheel cars were the coolest. That's why I wanted to be an open-wheel driver. They don't look like anything else on the planet. They're fascinating."

That term, "open wheel," is critical to understanding the world that Newgarden inhabits, as well as his nerve-jangling, body-stressing experience inside the car. It means that the tires extend from the side of the vehicle on wishbone-shaped suspension. We drive above our wheels. Open-wheel racers drive among them. The cars also have open cockpits, so the driver's helmeted head and gloved hands are exposed to the air, which is often rushing by at 200 mph.

What it's not is NASCAR, though as a Southern-born racer, Newgarden gets that misunderstanding a lot. Those "stock" Fords and Toyotas have roofs and fenders. They bump and jostle one another during races, which has its own thrills. Open-wheel drivers avoid touching like a hot stove, because tire-on-tire encounters usually send one or more cars sliding or spinning, if not flying. IndyCars are quicker through turns and nimbler under braking than stock cars. They are among the outright fastest long-distance race cars in the world, and driving them is a kinetic experience.

"They're very stiffly sprung, 1,600-pound cars," Newgarden says, sitting near his crouching beast. "There's almost no give. So all that feedback from the road — whether it's bumps, curb strikes, road surface imperfections — goes straight into your body. It really does feel like someone's kind of punching on you all over. Some of it's good. You have to absorb those impacts to understand what the car is doing. It tells you how the car is working."

With its bewildering speed, its micro-responsive steering and throttle, its intense g-forces in four directions and its real-time strategic team interplay, IndyCar demands a mental and physical stamina with few parallels. Newgarden, you could say, makes a living doing cataract surgery from a hammock inside a paint shaker installed in the world's fastest horizontal roller coaster.

Born at Vanderbilt Hospital and raised in Hendersonville on Predators games and Christmas at the Ryman, Josef Newgarden has emerged as one of the most accomplished and promising American race car drivers of his generation. He committed to the demanding and dangerous career 10 years ago at age 15. He finished high school online while winning races in Europe. He was crowned champion of the series that feeds into the top-tier IndyCar league, where he's now in his fifth season. Last year, he netted his first two wins at this level, the first right here at Barber, at the Grand Prix of Alabama.

This Sunday, Newgarden will start on the front row in the 100th running of the Indianapolis 500, a landmark edition of America's most epic and important race. Winning the huge Borg Warner Trophy is not one goal among others for open wheel racers. It's the singular reason for living and training. The 500, the largest one-day sporting event in the world, has the scale and intensity of a space shuttle launch. And Newgarden, who qualified second in a 33-car field, has a reasonable chance of winning.

In July 2004, 13-year-old Josef and his father Joey stood by a fence at New Castle Motor Sports Park just east of Indianapolis watching the big kids zip through hard left and right turns around a racetrack on "karts," the wasp-like vehicles that represent the bush league of American racing. They were pushing 90 to 100 mph, and it was intimidating.

"A lot of these kids were 5 or 6 years old when they started and had been racing there years," says Joey Newgarden. "I remember it like yesterday, him leaning on the fence saying, 'Dad, I just don't know if I'm daring enough to go off into turn 17 wide-open like that.' I said, 'That's all right. Don't do it. Or do it when it's time, if it comes to you.' He was a very smart kid."

Wary though he was, Josef discovered a preternatural nerve and car control in those high-speed turns. He found he was quicker than many of the teenagers with more experience. "Once we started [kart racing], I think my dad got hooked on it just as much as I did," Josef says. "For me, it was really easy to understand that I didn't want to do anything else." So they had some big family talks, and Josef set off for professional driving school in Sebring, Fla., at age 15.

The Old World spelling of Josef's name pays homage to his Danish mother. She and native New Yorker Joey settled in Hendersonville in 1986, where he ran and grew a national network of children's photography services. Josef grew up playing baseball and basketball, making up games in nearby Drake's Creek Park and attending Sumner Academy. He was clearly on track to be an athlete, but the first sign that he'd be leaving bats and balls behind came when he begged his father for a domestic go-kart. "My parents were not supportive of racing or anything motorized," he says. But that didn't last. "When I was 13, my dad finally kind of caved."

Racing school led to sports-car competition. He won races regionally and nationally, which helped net him a scholarship to live, practice and race open-wheel cars in Europe. In the fall of 2008, at 17, he ran a head-turning race on a historic track in Brands Hatch, England, passing multiple opponents to win the Formula Ford Festival. He was the first American to do so, helping him secure a manager and a year of racing on the great tracks of Europe in a feeder series for Formula One. That proved prohibitively expensive, but he returned to the U.S. and, in 2011, got a seat driving in the IndyCar equivalent of Triple-A baseball, Indy Lights.

"If that year didn't go well, I might have been done and without sponsorship," Newgarden says. "It might have been difficult to keep going."

But he owned it. He won the season's first race at St. Petersburg, Fla. In New Hampshire, he lapped the entire field in a winning effort, which is just about unheard of. He'd win three more times in 14 races and take the season championship. But the most vivid harbinger of Josef's potential came early that season at Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

Two days before the Indy 500, the Indy Lights series holds its Freedom 100 on the storied track. The 2011 race is viewable on YouTube, and it is breathtaking, though some of the context is not obvious. Remarkably, it was Newgarden's first race on an oval track — those are faster, closer and more tactical than the twisting, turning road courses he was used to. And conditions that day were poor, with temperatures in the 50s making the surface a slippery, malevolent runway.

But as you can see in the video, Newgarden runs at the front as if he's been racing ovals for years. He and two other drivers slip in and out of first place like a school of exuberant barracudas. About the midpoint of the 100-mile race, cars behind them begin to lose it, spinning out and winding up against the wall or in the infield of dashed dreams. Then a wreck of cinematic proportions. With three laps to go, Venezuelan driver Jorge Goncalvez slides hard into an infield wall. His fuel tank explodes in a fireball and blows the car into pieces. The cockpit flips and skids hundreds of yards upside-down, with the driver's helmet just inches from the track, before the chassis rights itself. The race can't be restarted, and Newgarden wins under a yellow flag because he was leading at the time of the accident. The other driver was hospitalized briefly but was ultimately fine.

From this one race, two takeaways: The composure, pace and adaptability Newgarden showed that day helped earn him a spot in IndyCar in 2012 (signed by the sport's top female executive/driver Sarah Fisher, who used to race with Nashville's Dollar General as her chief sponsor). Also laid bare was the cold truth that in a heartbeat, racing can spiral into devastating violence. Newgarden has seen two fellow drivers killed during his pursuit of an IndyCar career, including friend and mentor Justin Wilson, who was fatally struck in the head by debris in August. Newgarden and his family harbor no illusions about the danger, especially at 225-plus mph Indianapolis.

"It scares the hell out of me every time he or any of those guys are on that track," says Joey. "I'm so happy he's driving in an era where safety has come so far. But it's still dangerous. It's made him very aware of how precious life is and how quickly it can go."

As the defending race winner at the Barber Motorsports Park, Newgarden gets attention from the media as he preps for the race. He's asked how it feels to return to his "home track," so designated because it's the closest on the IndyCar calendar to Nashville. He praises the circuit for its European style flow, challenging turns and stomach-lifting elevation changes. It's also lovely and pastoral, known in the business as "the Augusta of Motor Sports." Last year's win, Newgarden says, was a result of everything clicking throughout the weekend and his car passing a key rival at a critical point. "Smooth sailing," he calls it. Sometimes it happens.

Now the challenge is to repeat, a process that begins with strategic number crunching and which becomes tangible on Friday during two sessions of highly structured on-track practice. Here, any illusion that the driver is a diva or a hero on a pedestal is dispelled. Newgarden slips into his car and nearly vanishes; he becomes an extension of his racing team more than the other way around.

Sarah Fisher's team evolved into Ed Carpenter Racing, which is one of the smaller teams, a kind of indie Indy, if you will, but a well-financed and successful one. Owner and part-time driver Carpenter has three career wins. At Barber he's in owner/supervisor mode, watching over the weekend's complex dance of team, driver and car. He says Newgarden's strength is his willingness to learn: "He's not afraid to look at weaknesses and improve on them. Some guys don't want to act like they have any."

As Newgarden jets away from his pit on Friday at 11:02 a.m. for his first practice runs, his 21 car squalls and yelps like some huge baby animal. About 20 crewmen in team uniforms are wearing poker faces and tending to specialized jobs. One guy has a black case of shock absorbers stored as if they're lightsabers. Others monitor reams of car data on a dozen video screens and laptops. Newgarden makes runs of varying lengths, and every time he returns, crewmen attach umbilical cords to the car, remove covers and tires and make minute adjustments to the suspension and brakes.

Newgarden's job is to execute the team's plan for testing the car's performance while memorizing the limits of the track. Every high-speed turn is a life-or-death act of faith in his team, because they conjure the suppleness of the suspension and the aerodynamic down force required to keep roughly 2 square feet of rubber attached to the road under huge lateral stress. In turn, the team trusts Newgarden to test those tolerances without smashing up the car.

"The great drivers are able to take the car past its limit and still control it," Newgarden says, citing 2014 IndyCar champion Will Power as an example. "He's very good at exploring that area without wrecking. You have to be able to do that." A driver also should be mellow and positive when the machinery fails, because it inevitably will. "He always stays pretty upbeat," says his engineer Jeremy Milless. "Even if we roll out and we're not great, he knows that we could just be a couple changes away from being right at the top. There's a lot of drivers I've worked with who, let's say, are pessimists, and he's an optimist. He's very team."

Qualifying on Saturday determines the order in which the cars will line up to start Sunday's race. Newgarden's car is set up to excel on single laps, with almost no fuel (lighter is faster) and tires chosen for maximum grip instead of durability. Newgarden just slips into the final heat with the top six, covering the 2.3-mile, 17-turn track in just over one minute and seven seconds, a third of a second behind the fastest car. With the pressure on, some small adjustments to the car give him something more to work with, and Newgarden pops off a 1:07:02, fast enough to start third in Sunday's race.

Watching the qualifying runs through the fence next to the pit box are Newgarden fans Andy Skirvin and Matt Dufek of Indianapolis. Skirvin says he's been following the sport for 25 years and feels like Newgarden is a superb ambassador for what's shaping up as a great era of motor racing. "You gotta win early to make it, and he did," says Skirvin. "He's truly the future of the series." Dufek notes that while Newgarden's years in Europe were crucial to the schooling of a great open-wheel driver, he is grateful to Sarah Fisher and Ed Carpenter for betting on an American. While IndyCar is an American league based in Indianapolis, two-thirds of its drivers come from Brazil, Colombia, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Italy, Japan, England and France. Only one of the seven Americans in the league today, Ryan Hunter-Reay, has won a season title and an Indy 500.

Newgarden and team need a good race, truth be told. The first three runs of 2016 came with random problems and Josef hasn't finished better than sixth. But on this clear Sunday afternoon, his car is lively from the start, improving from third to second by the fourth lap, thanks to a daring, clever pass on the aforementioned Will Power. A drone of engine noise settles over the track's green and wooded hillsides as the race unfolds with plenty of passes and on-track action but no wrecks. That's good for the fans, but grueling for the drivers.

"We don't have power steering or power brakes," Newgarden says. "Nothing is assisted." Those big wings press the car to the track with several thousand pounds of force, so turning the steering wheel is like lifting a 20- to 30-pound weight for two hours, he says. He's 6 feet tall and 185 pounds, so in the fastest turns, he becomes 800 pounds of compressed ribs and lungs crushing against the nylon and carbon fiber of his cockpit. He actually has to hold his breath. When marathoners run, we see their legs pumping. We see them breathing. A driver's exertion is directed differently but it's no less real, and some IndyCar races last longer than a winning marathon effort. Newgarden's heart hovers around 170 beats per minute when the flag is green.

With two laps to go, Newgarden is running in fourth place, but he passes Power again to steal the third step on the podium. It's a solid run, earning some good points toward the championship, a trophy and a spray of Champagne. After some TV interviews in front of the winner's circle, he takes his sore muscles up to a press conference where he jokes that if it seems like he's fine, he's only acting. "The cockpit of the car gets really hot. They're really beasts to drive. You get short of breath. We prepare for days like today. But it's tough."

The team folds up its tent and stows its gear just hours after the checkered flag. The car is hoisted by a lift to its cozy slot in the roof in the team trailer, and everyone is off to concentrate on Indianapolis and the month of May.

"The whole month's a pressure cooker," Newgarden says. "You have so much time to work on your car and to get things right. Then it takes you three hours to run the race — 500 miles — and you've been there for three weeks preparing for this one moment. And if you don't get it right, well, sorry, try again next year."

In 2015 he finished ninth, his best ever but fundamentally a disappointment.

"It wasn't the worst result finishing top 10. But that's not what we go to Indy for. The only reason to go to Indianapolis is to win."

Craig Havighurst is the author of "The Sound of Speed," an online essay about Nashville audio designer Steve Durr and his role behind the scenes at the Indianapolis 500.