New Leaf students explore a fallen tree on their preschool campus.

Nestled behind the First United Pentecostal Church in West Nashville is a two-story brick house, surrounded by 33 acres of grassy fields, a meandering creek, a grove of trees and a bamboo forest.

In the field just behind the house, 4-year-old Neal Albert runs and drops to his knees in the dirt. He wants to dig. His friend yells “Quack!” and continues running past him. Neal explains that his shark-tooth necklace makes a good shovel, especially the pointy part — but when you put it in your mouth after you dig, it doesn’t taste good.

That’s one of many lessons Neal has learned at A New Leaf, a Reggio Emilia-inspired forest school on Charlotte Pike. Reggio Emilia is an educational philosophy centered on the exploration of the child and innovative curriculum. At A New Leaf, students are in charge of their own learning.

“Reggio Emilia is a project-based approach, and we value what we call the ‘100 languages of children,’ ” says Elle Harvey, founder and executive director of A New Leaf. “There are numerous ways of looking at things from different points of view and exploring different materials and ideas. We look at language arts and math, as well as the language of water, clay — like Neal did — wind and everything else you can see around you. They guide their learning, and we see where they gravitate towards. If they’re interested in something, we document that, what they say, and then we think about what we can do with it to feed that learning path.”

Neal’s mom Mallory Albert says prior to coming to A New Leaf, Neal was not excited to go to school. But now that he has somewhere he can run, play pirates and dig in the dirt using his shark-tooth necklace, he’s thriving.

“We were in another program for a very short amount of time, and he wasn’t doing well there,” says Albert. “He didn’t look forward to going. But here, he gets to explore the things that he’s interested in, because he’s given time instead of being rushed through in a really regimented way. He loves the outdoor space here the most and how open it is. He can be a pirate or a cook or just play in the sand. He shines when he’s outside.”

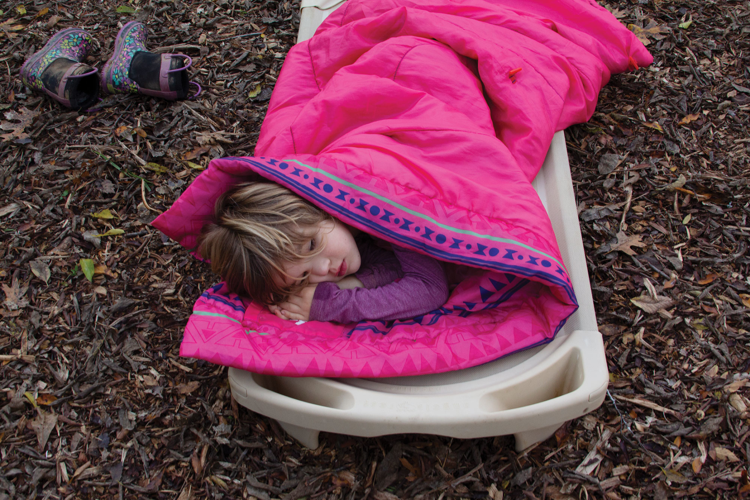

A student naps outside.

Harvey says she discovered the Reggio Emilia approach years ago when she was looking for a preschool for her own son, who is now 20. After much searching, she became frustrated that there weren’t any places her son could explore in the ways she thought a child should.

“He tried a few places and was really unhappy, crying every day going to school,” she says. “And I thought, ‘Goodness, that’s no way to have to feel about going to school.’ We moved to Austin, and that’s when I explored a local cooperative nursery school where they used the Reggio approach.”

A few years later, Harvey and her family moved to Nashville, and she wanted to bring the type of environment her son had learned in to her new city. Harvey says both her background in biology and her respect for the Reggio Emilia approach led her to creating a Reggio-inspired forest school. Fourteen years later, there are now several Reggio-inspired schools in the city — and A New Leaf is the oldest.

“Children are not a vessel that we fill,” says Harvey. “They have ideas, and they are exploring them. They have extremely busy and complex brains, and with Reggio, we are co-researchers with the students. That’s what brings in the language of discovery. It’s really a wonderful way to educate and be.”

Maria TeSelle, a teacher at A New Leaf with a master’s degree in early-childhood education, has been with the school for almost three years.

“When the children are outside, they develop the kinds of skills we want to see in early childhood education,” says TeSelle. “They learn how to talk to each other, and work together on a plan. They’re more coordinated — they can run on uneven surfaces, whereas most children have a rubberized playground. They’re learning motor skills, and the academic skills like literacy and numeracy come as a part of the whole-child, multi-domain approach.”

Students have lunch outside with teacher Ericka Ward.

Lisa Jambusaria’s daughters Indy (4-and-a-half) and Leela (2-and-a-half) both go to A New Leaf, and she says she sees both benefiting from the approach.

“I think their learning is more as a whole instead of little landmarks,” Jambusaria says. “Indy is writing her name and can trace letters and count, but she can also recite planets and tell me about their composition. She was counting to 10 in Japanese last year, and when we go on hikes, she’ll say, ‘That tree is this type because it has white bark.’ She’s learning things that are more tangible and building a foundation that she can put a bigger picture on later.”

“We see so many young children getting discouraged from loving things,” says Ericka Ward, another teacher at A New Leaf. “Growing up, we all heard, ‘Don’t touch that,’ or, ‘Don’t get dirty, I just bought you that shirt!’ But the kids, they’re curious. We want them to feel confident in their own curiosities and not shut those things down. I want them to be able to approach new ideas with flexibility and playfulness and a strong sense of self to be confident in who they are and their ideas and the things they love.”

Cindy Ligon, director of McKendree United Methodist Church Day Care, has been working with children for almost 30 years. For the past six, she and the McKendree staff have been using the Reggio approach, and Ligon says one of its greatest benefits is its flexibility.

“You can have A New Leaf that is very nature-based, with all the acres of the wonderful beyond, and then you can also have McKendree in the middle of the city,” says Ligon. “Our outdoor space is on top of our building. We are an urban program, but we share many of the core values about how children learn and grow.”

Despite the difference between separate programs that use the method, Ligon says the child comes first, even using the same metaphor as Harvey — saying that children are more than empty vessels to be filled.

“They are going to create their own world by being social and curious. If you think children are really curious and competent, you would allow them to follow their own interests and let them create their own view of the world.”

Ligon and Harvey represent just two Reggio schools in Middle Tennessee that are a part of the Tennessee Reggio Study Group, a support space for early-childhood educators employing the approach in their classrooms. Jody Barger, executive director of the Reggio-inspired Stonebrook Day School in Murfreesboro, says the group provides her with inspiration to keep letting the children teach her.

“To allow the children to have time to learn and ask questions and form their opinions, I think it’s just natural,” she says. “When we moved to this, I thought, ‘Why haven’t we been doing this all along?’ It’s a respectful way to work with children, giving them value to their thoughts, work their art, and it teaches them that they’re not just little kids. They’re citizens too, with ideas and thoughts and feelings that are worth listening to.”

Barger says if more schools allowed students time to learn and explore their own interests, student engagement wouldn’t be an issue.

“I can’t help but think if our public school system implemented some of this, that maybe the children’s grades would be higher, and maybe there would all around be more excited students,” she says. “Going back to the whole theory of respect, it’s showing these children that you’re respecting them enough to follow their own interests and let themselves guide their education. And in respecting them, you’re teaching them to respect others — those traits that we want children to have.”

Students and teachers gather for their morning meeting in front of the “Book Castle.”