Tracy Silverman

One pleasant April morning, Tracy Silverman is in his home studio in Nashville, demonstrating the range of his electric violin. There isn't a lot of formal repertoire for this unusual instrument, which, with its whining reverb, often sounds more like Jimi Hendrix's guitar than Jascha Heifetz's fiddle.

So Silverman plays his own music. He begins with a movement called "La Danse" from his Second Electric Violin Concerto. Silverman found inspiration for this piece in Henri Matisse's Fauvist painting of five nudes dancing in a circle, in a sort of primitive, ritualistic "Ring Around the Rosie." In his concerto, Silverman imagines the dancers have improvised their own themes.

The piece opens with the first dancer's motif, a catchy, syncopated fiddle tune that serves as a kind of invitation to a primeval barn dance. Silverman taps a pedal on the floor and the theme loops into a rhythmically vital ostinato. A new melody, this one sounding like bright, lyrical electric guitar notes, then enters the mix, conjuring Matisse's second dancer. As "La Danse" unfolds, Silverman adds layers of electronically looped melody to create a shimmering polyphony. The climax evokes one of Eric Clapton's triumphant electric guitar wails.

Noticing with amused satisfaction that his visitor's jaw has fallen to the floor, Silverman decides to complete his musical conquest with a sonic coup de grace. He begins to play a standard, Gershwin's sonorous duet "Bess, You Is My Woman Now." Heifetz, the legendary classical violinist, recorded it with piano accompaniment in 1946.

But Silverman has no need for a piano. His six-string electric violin not only encompasses the entire range of an electric guitar but reaches nearly to the bottom of a cello's dark register. Unlike a traditional violin, which is generally limited to playing one note at a time, Silverman can actually strum the electric violin with a bow, producing a sound that's like strumming a guitar, and play multi-note chords. In "Bess, You Is My Woman Now," he accompanies himself, adding big, chromatic harmonies and bass notes to the familiar theme.

"I played that arrangement for Terry Riley," says Silverman, beaming with boyish pride as he recounts the reaction of his musical hero. "As soon as I finished playing it, he asked to hear it one more time."

On Thursday, May 3, Silverman will get the chance to impress the composer again. The occasion is the world premiere of Riley's Palmian Chord Ryddle for Electric Violin and Orchestra with the Nashville Symphony Orchestra at Schermerhorn Symphony Center. Later this month, the violinist and the NSO will take the concerto, which was written specifically for Silverman, to New York City, performing at Carnegie Hall on May 12.

For composer and soloist alike, and for an orchestra hungry to prove itself on the international stage, the concerts promise to be milestones. The piece represents an ambitious departure for Riley, one of America's most influential avant-garde composers, an enigmatic figure who has spent more time playing in small clubs than posh concert halls. For the NSO, the work is a potential signature piece that could boost the orchestra's reputation as a champion of contemporary classical composition.

Silverman likewise stands to benefit from this bold venture, which will soon see him performing on one of the world's most august stages. And on this morning, playing Gershwin's deeply affecting love song in his Lipscomb-neighborhood studio, Silverman performs with gusto, pleased to see his visitor plainly dazzled.

Then he seems to pull back the reins.

He doesn't want anyone to think he's full of himself. That he's conceited. That would be very un-Terry Riley-like. As the counterculture composer would no doubt say, a craving for adulation is one of the root causes of human suffering. Buddha indicated as much in the second of his Four Noble Truths. So Silverman deflects praise with one of his favorite refrains.

"I don't actually have any musical talent," says the violinist, who speaks with enough earnestness to almost make you believe him. "But I've always been extremely sensitive to music."

The two musical figures behind Palmian Chord Ryddle have taken so many unconventional turns in their winding careers, it seems only inevitable that they should intersect. Riley made music history in 1964 with the premiere of his In C, a sparkling, repetitive piece that all but launched the minimalist movement in music and greatly influenced the likes of John Adams, Philip Glass and Steve Reich. But unlike his minimalist successors, Riley did not go on to become a major composer of symphonies, operas and concertos. Instead, he pursued an alternative lifestyle and career, devoting himself to hippie culture and Buddhist philosophy while mostly playing jazz, avant-garde classical and world music with small ensembles.

"Riley hasn't written a lot of big orchestra pieces," says NSO music director Giancarlo Guerrero, who will conduct the Riley concerto in Nashville and New York. "But he really steps out with this concerto, because it is a big, ambitious orchestral work."

Silverman, 52, likewise followed an unorthodox path. He has the musical pedigree of a thoroughbred: solo debut with the mighty Chicago Symphony Orchestra at 13; graduation from Juilliard at 20. Yet instead of settling into a comfortable career playing classical warhorses with orchestras, the young Silverman turned his back on classical music. After Juilliard, he traded in his four-string acoustic violin for one of those sleek, modern, six-string amplified models. And instead of Tchaikovsky, he started playing jazz and rock in small (and sometimes seedy) clubs.

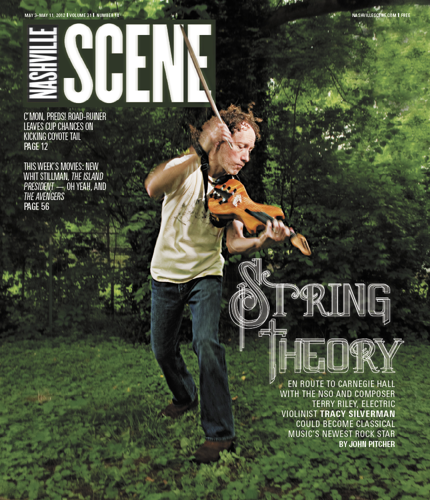

The electric violinist's career course is matched by an appropriately offbeat look. Silverman wears his hair in long, tightly wound curls — a bit like Kenny G, though the comparison might make him wince. Silverman is understandably sensitive to any smooth jazz comparisons, since his musical role models were all icons of rock, modern jazz and soul: Hendrix, Miles Davis, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles. Nevertheless, Silverman has made a career, in part, recording for Windham Hill Records, the label of ambient music stars such as pianist George Winston. Moreover, he often tours with easy listening hunk and crooner Jim Brickman.

Silverman's favored attire is pure rock 'n' roll: blue jeans, T-shirts and a rock star's razor stubble. While demonstrating "Bess, You Is My Woman," he wears a T-shirt emblazoned with the name of one his favorite restaurants, The Smiling Elephant on Eighth Avenue. The violinist has adored spicy Thai food and anything prepared with garlic for almost as long as he's loved music — that is, pretty much from the start.

Born in 1960, Silverman grew up in a family of music lovers in Peekskill, N.Y., just north of New York City. His parents were teachers, not musicians, but the future violinist's father had an extensive collection of classical and jazz LPs. One of those records had a profound effect on the young listener.

"When I was about 4 years old, I listened to my dad's recording of the Sibelius Violin Concerto, and it was so beautiful that it actually made me weep," says Silverman, who as a teen made the Sibelius concerto a specialty. "I was always super-sensitive to music."

Not long after discovering Sibelius, the boy rode his tricycle past the home of a neighbor, who was the concertmaster of a local orchestra. The neighbor was practicing the sensuous violin solo from Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade. Silverman found the sound to be so captivating that he raced home to get his older brother.

"I told him there was a woman singing beautifully in this house down the street, and that he should go hear her for himself," Silverman remembers. "When we got to the house, my brother said, 'Hey, that's not a woman singing, that's somebody playing the flute.' "

Recalling those stories brought back such fond musical memories for Silverman that he had to go search his studio — located in the detached garage behind the modest Nashville ranch house he shares with his wife and their children — for an acoustic violin. With instrument in hand, he began playing through favorite passages of the Sibelius concerto and Scheherazade. It's likely been years since Silverman has performed either of those classic works. As an electric violinist, he never had a reason to. But he nailed them all the same.

Silverman began formal violin lessons at 5. Within three years, he'd made enough progress to get into Juilliard's pre-college division. But then his father, who was working on a doctorate in education, got a job teaching at Beloit College in Wisconsin. The family moved instead to the Midwest.

Not surprisingly, there were no Juilliard-level violin teachers in Beloit. So two or three times a week, Silverman and his father drove 97 miles to Chicago, where the young violinist entered the preparatory division of the Chicago Music College. There, he began lessons with a young violin teacher named Debbra Wood (now Debbra Wood Schwartz).

Silverman credits Schwartz with providing him with a thorough foundation in violin technique. "I learned almost everything I know about violin from her," he says. In turn, Schwartz remembers the prepubescent Silverman as already being the complete package.

"Tracy had everything it takes to become a successful classical musician," says Schwartz, who spoke recently by phone from her current home in Oakland, Calif. "He was smart, gifted, had phenomenal chops and most importantly had a good sense of humor. You just can't make it in this business if you take yourself too seriously."

But Silverman was serious about his music. Schwartz recalls the 12-year-old violinist coming to lessons having read Mozart symphonies in their full orchestral scores. He would enter Schwartz's studio, chirping enthusiastically about all the ingenious ways the Salzburg composer had connected his ideas. Call it professional courtesy: It was a classic case of one prodigy admiring the work of another.

Silverman was also intent on mastering the Sibelius concerto. "We worked on that piece a lot when he was about 13 or 14," Schwartz says. "He loved that piece, and finding just the right interpretation became his mission." Not surprisingly, Silverman did conquer that work. Schwartz credits Silverman's success to his unusually mature musicianship.

"Tracy had an appreciation for sound quality and color that really distinguished him from all the other students his age," Schwartz says. "He also had unusually strong musical opinions, something that was really rare for pre-college level violinists. I truly believed that there was absolutely nothing he couldn't do as a musician."

Schwartz and Silverman eventually parted company. The 17-year-old virtuoso continued to follow his (perceived) destiny, heading to New York City to enroll in the famed Juilliard School. Schwartz left Chicago and moved to Oakland. There, she struck up a friendship with an up-and-coming San Francisco-based composer named John Adams. Her close association with both Adams and Silverman would one day give this otherwise unassuming violin teacher an oversized role in the history of contemporary American music.

At Juilliard, Silverman was considered a big talent, but he was no longer singular. He certainly wasn't in Beloit anymore. The conservatory's practice rooms were filled with future fiddle stars, from the wildly eccentric Nigel Kennedy to the elegantly refined Robert McDuffie. Some aspects of the Juilliard experience were priceless — for instance, Silverman got to study with the legendary teacher Ivan Galamian, whose roster of students included everyone from Dorothy Delay to Itzhak Perlman. But from the beginning, there was at least one thing about the Juilliard environment that Silverman didn't like.

"I felt that there was too much emphasis on technique and perfection," Silverman says. "I knew violinists and pianists who were spending eight or more hours a day in their practice rooms. Sometimes, you felt more like you were competing in the Olympics than making music."

Silverman also began sensing another problem with classical music. Stuck on the summit of Mt. Olympus, the art form seemed to lack a certain relevancy to the contemporary world. Outside the hallowed halls of Juilliard, Silverman had a hard time finding anyone his age who listened to classical music. How could he blame them? So much of the music seemed mired in the distant past.

His low point came one day when he was searching Schwann Opus — a back catalog of published classical recordings — for a specific version of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto. To his chagrin, he found that the piece had been recorded many times — 57 versions were listed.

"I realized at that moment that I didn't want to spend the rest of life doing what had already been done time and time again," he says.

When Silverman graduated from Juilliard, he put his acoustic violin back in its case and left classical music. He wouldn't return to the genre for another 22 years, when America's most influential classical composer finally sought him out.

[page]

Even before he left Juilliard, Silverman already had a sense of what he wanted to do. He wanted to become a great jazz musician. Maybe a rock star. Problem was, he didn't play electric guitar, alto saxophone, Hammond organ or any of the usual instrumental suspects of jazz or rock.

That turned out to be a blessing, Silverman now believes, because it forced him to start building his own six-string electric violins. But even more pressing than his choice of instrument, Silverman realized he had to do something about his conspicuous lack of jazz and rock chops.

"The first time I tried playing at a New York jazz club, called Sweet Basil, I got kicked out," Silverman says, a mixture of embarrassment and amusement settling on his face. "It was clear to everyone that I didn't know what I was doing."

So Silverman began the long, slow process of educating himself. He took John Coltrane's long-playing masterpiece Giant Steps and transcribed it, note for note. He began taking voice lessons, believing that all pop musicians should know a thing or two about singing. And he listened to such great soul singers as Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles, striving to understand what made their performances so emotional and immediate.

"I learned that you can't actually notate what Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles are doing," Silverman says, marveling. "The real magic in a lot of music happens between the notes."

That's something Terry Riley has known for a long time.

Every morning, this founding father of minimalism makes a point of singing Indian ragas at his Sri Moonshine Ranch, a 26-acre spread located three hours from San Francisco near Nevada City. Bearded and bald, the 76-year-old composer sings Indian music with a rough-hewn voice that Randy Jackson would no doubt call "pitchy." But unlike your typical American Idol contestant, Riley wouldn't consider that a put-down.

"There is no such thing as absolute pitch in Indian classical music," says Riley, who spoke recently by phone from his ranch. "Indian music is full of microtones, so you need to know how to sing between notes."

Nearly 50 years after In C made him one of the world's best-known composers, Riley remains an enigmatic figure. Understandably, he's almost always referred to as a minimalist. Yet he has spent the bulk of his career inhabiting the worlds of jazz, pop, avant-garde classical and Indian music. "You can't really define Terry Riley's music," says conductor Guerrero. "He's just been into everything."

Born in Colfax, Calif., in 1935, the easygoing Riley grew up in the Sierra Nevadas. His first love was mainstream classical music, and he had aspirations of becoming a concert pianist. But unlike Silverman, Riley wasn't a prodigious talent. So when he entered the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, he found that his skills lagged far behind many of the other piano students.

"I realized that if I wanted to have a career in music, it wasn't going to be as a concert pianist," Riley says.

So Riley switched to composing. He began studying at the University of California at Berkeley, and he supported himself playing jazz piano in bars. Eventually, he developed into a formidable improviser.

One of Riley's classmates was another young composer destined for greatness: La Monte Young. Initially a devotee of Anton Webern's 12-tone music, Young pioneered a style of writing called long-tone technique. Long-tone compositions often consisted of just a few notes held for incredibly long durations.

The critic Alex Ross has compared the momentum of these pieces to continental drift. But to Riley, Young's innovations were a revelation.

"La Monte stripped music of melody and rhythm, leaving it with only its absolute most essential tones," says Riley. "In the process, he basically invented ambient music."

Riley saw boundless potential in Young's technique. For instance, this minimalist approach to music could allow a composer to write a great piece of keyboard music that even rank amateurs could play. "Most pianists don't have the technique to play Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 31," says Riley. "But almost anyone can learn to play a measure of notes in C major that's repeated over and over."

And that's about as concise a definition of In C as you'll ever get. The piece, which premiered on Nov. 4, 1964, consists of a chart of 53 modules — or brief motivic figures – that were mostly in C major. Players proceed from one module to the next at their own pace. The highest Cs on the piano are repeated nonstop and without variation throughout the work, establishing the pulse and giving the piece its name.

Certainly, Riley couldn't have hoped for a better premiere. His all-star ensemble included a then 28-year-old Steve Reich, along with avant-garde figures such as Morton Subotnick, Jon Gibson and Pauline Oliveros.

"I knew from the moment I finished writing this piece that it was going to be important, because it was totally original," Riley says. "And I doubt a day goes by when it's not performed somewhere in the world."

In 1971, Riley began teaching at Mills College in Oakland. For the next decade, he all but disappeared from the public eye. Around this time, he began making frequent trips to India, where he and La Monte Young began studying with the legendary Hindustani vocal master Pandit Pran Nath. Riley also immersed himself in Buddhist philosophy.

Starting in the 1980s, Riley began to reap the rewards of a longstanding relationship with the genre-defying Kronos Quartet, writing album-length works for that ensemble such as Salome Dances for Peace. He also started touring with his own small ensembles, presenting an eclectic mix of jazz, ragas and contemporary classical music. These performances continued for the next dozen years. During a tour of Germany in the late 1990s, Riley met Tracy Silverman.

Silverman had spent his first decade after Juilliard studying jazz improvisation. He also became a path-breaking electric violin virtuoso and composer. One of his most important innovations was a technique he called "strum bowing." In this approach, an electric violinist taps the bow vertically on the strings, playing only subdivisions of the beat. The resulting sound is almost indistinguishable from a funky electric guitar riff.

During the 1980s, Silverman also spent countless hours learning how to duplicate Aretha Franklin's miraculous technique of sliding from one note to the next, an ability that allows her to explore every nuance of tonal color between the melodic cracks. All this hard work landed Silverman a plum post in 1993, when he became first violinist with the internationally renowned Turtle Island String Quartet.

In his four-year tenure with the group, Silverman learned to fuse contemporary classical music with folk, bluegrass, swing, bebop, funk, R&B, new age, rock ... you name it. At any given moment, he could sound like Jimmy Page or Itzhak Perlman. There was really no other instrumentalist like him. By 1997, Silverman was ready to go solo, and one of his first gigs was in Bremen, Germany — the place where he met Terry Riley.

Silverman found the famous Riley, with his soft-spoken manner and penchant for wearing colorful caps, to be utterly charming and approachable. Riley, for his part, was fascinated with Silverman's six-string electric violin.

"Tracy's violin is practically like an orchestra in and of itself," Riley says. He was also impressed with Silverman's versatility.

"He liked the fact that I could play jazz, rock, classical, world music, whatever," says Silverman. Not surprisingly, Riley soon invited Silverman to appear with his own group, the Terry Riley All-Stars. "It was amazing," says Silverman. "At that point I actually became a part of Terry Riley's inner world."

Arguably the most important concert that Riley and Silverman gave together happened in 2002, at Yoshi's Jazz Club and Restaurant in Oakland. That night, Silverman's former teacher, Debbra Schwartz, talked composer John Adams into attending the concert. Schwartz was close to the great composer; her son had been one of Adams' favorite composition students.

Adams was then working on a commission from the Los Angeles Philharmonic for a major piece to inaugurate the opening of the new Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2003. He wanted to write a piece of music that embodied the feel of being on the West Coast. He initially thought of writing a piece for orchestra and narrator — he had the actor Willem Dafoe in mind — that featured readings from some of Jack Kerouac's works.

But then he heard Silverman. In his autobiography, Hallelujah Junction, Adams wrote about this concert, giving a somewhat technical and dispassionate description of Silverman's violin: "The instrument, because it shared the same amplified properties with the electric guitar, could sustain long, bending portamenti, allowing slides between notes that mimicked a great jazz vocalist, a Hebrew cantor, or a Qawwali mystic singer. I was enchanted by this instrument and by Tracy's manner with it."

Adams' prose doesn't hint at how enthusiastically he reacted to Silverman's playing. "After the concert, someone mentioned that John Adams wanted to meet me, and my only thought was, 'Boy, I hope I don't have food between my teeth,' " remembers Silverman. "But when I actually saw Adams, he was jumping up and down with excitement, wanting to know everything about the violin and the foot pedals."

"John had spent years searching for a sound that would bridge gap between Asian music and the West, and he found it the moment he heard Tracy play," says Schwartz. "So of course he was excited."

In fact, Adams resolved to write a new piece for Disney Hall, a concerto for electric violin and orchestra called The Dharma at Big Sur. The second movement, dedicated to Terry Riley, is called "Sri Moonshine." And Silverman became the missing ingredient Adams had been seeking.

In 2000, Silverman became part of a national trend. He was one of thousands of exotic-food loving, NPR-listening, art-house-movie-going denizens of the West Coast who decided to relocate to Nashville. The demographic shift was remaking Music City from a quaint Southern industry town to more of a cosmopolitan city — one reason you can attend a Nashville Symphony Orchestra concert or an art gallery opening these days and be hard pressed to find anyone with a Middle Tennessee accent.

Like so many transplants, Silverman made the move in part for financial reasons. The staggering cost of real estate in the San Francisco Bay Area had priced the violinist out of that market. But for the increasingly successful touring artist, music also played a role.

Silverman first visited the city to take part in an improvisation orchestra. Whatever he was expecting, he says, he didn't get it. Instead, he found himself among other virtuosos, such as bassist Edgar Meyer, banjo master Béla Fleck, saxophone phenom Jeff Coffin and drummer Roy "Futureman" Wooten. These were musicians just like Silverman, artists who were constantly crossing musical boundaries, exploring multiple styles.

"When I went back to the Bay Area, I told people that Nashville is not what you think," says Silverman. "In fact, the place Nashville reminds me most of is Brazil, because both places are completely open-minded and accepting of all kinds of music."

Nashville has become an effective base of operation for Silverman. He now records here with his aptly named rock trio Eclectica, featuring Wooten on drums and Steve Forrest on bass. He's also a busy teacher, working with music students at Belmont University.

In 2006, Silverman married his wife Stephanie, who is now executive director of The Belcourt. Under her management, that theater has blossomed into an arthouse with a national reputation and a thriving nonprofit arts organization.

Silverman's arrival in Music City didn't escape the attention of Alan Valentine, the Nashville Symphony Orchestra's ambitious and entrepreneurial president. Valentine had used the excitement generated by the NSO's first visit to Carnegie Hall in 2000 to launch a major fundraising campaign. Money from that endeavor ultimately led to the construction of the Schermerhorn Symphony Center, named for the orchestra's late music director Kenneth Schermerhorn.

Valentine was especially impressed with the success of The Dharma at Big Sur. In the years since Schermerhorn's death in 2005, the NSO had gained notice — not to mention seven Grammy Awards — for its interpretations of contemporary American music. Perhaps Silverman could be helpful. Since 2009, the orchestra has also had a new music director in Giancarlo Guerrero. In Valentine's opinion, it seemed like a good time for the NSO to return to Carnegie Hall. A new festival called Spring for Music offered a way.

The festival, launched two years ago, invites orchestras from around the country to compete for the chance to play at Carnegie Hall. Six orchestras are selected for — among other things — the adventurousness of their programs. Valentine figured a new concerto for electric violin might be the ticket to get the NSO back into Carnegie Hall.

"I called Tracy and told him I'd wanted to commission a new electric violin concerto for him, and I asked him to submit a list of composers he was interested in," says Valentine. "Terry Riley was the first composer on his list."

With commission in hand, Silverman traveled back to Sri Moonshine to confer with Riley. The composer wanted Silverman to show him the full range of his six-string electric violin. Silverman played him music from his own two violin concertos. Especially ear-opening was his performance of "Bess, You Is My Woman Now."

"I realized after hearing 'Bess' that the electric violin can play a lot of its own accompaniment notes," Riley says. "That allowed me to write an orchestral score with a lighter texture, since the electric violin was able to take care of itself and play a lot of its own accompaniment."

Riley says his concerto's fanciful name, The Palmian Chord Ryddle, came to him in a dream. The work's opening tonality, the so-called eight-note Palmian chord of D, E, F, F-sharp, G-sharp, A, B and C is in fact a simple polychord — D major and D minor chords spiced up with a few extra color notes.

The spelling of "Ryddle" is intended to suggest an ancient origin for the chord. The word also implies that the resolution of the chord will be a puzzle for much of the concerto's 35-minute duration. For Silverman, The Palmian Chord Ryddle isn't so much a mystery as it is an irony. Faced with the perennial question — how do you get to Carnegie Hall? — Silverman has seemingly discovered a Buddhist answer: Just let it happen.

"When I left classical music, a lot of people were disappointed, especially my parents," says Silverman. "But if I hadn't taken up jazz, rock and world music, I never would have had gotten to play the Adams and Riley concertos. So in a weird sort of way, my life has actually come full circle."

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.