Forty miles from downtown Nashville, two red-and-white towers stick up out of the Gallatin Fossil Plant like twin cigarettes snuffed out on the bank of the Cumberland River. Down the road a bit, work trucks drive down a dirt path past a small retention pond, and across the street a message is painted on a water tower, in full view of anyone driving into the plant: “WORK SAFELY.”

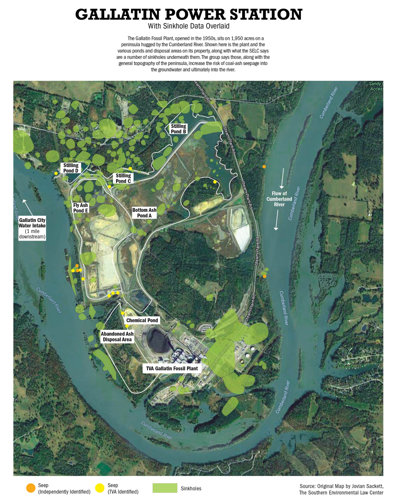

The Gallatin plant is one of eight coal-fired power plants operated by the Tennessee Valley Authority, six of which are in Tennessee. It burns four million tons of coal annually, enough to power 300,000 homes, according to the TVA. That means it also produces coal ash, the toxic byproduct of coal-fired power production, and a lot of it — up to 235,000 tons each year, all of which, until recently, was disposed of in wet-storage ponds on the property surrounding the plant. These ponds make environmental groups — who have historically called for coal ash to be buried in lined landfills instead — nervous for two reasons: They provide an opportunity for coal ash to seep below the pond and contaminate groundwater; and their walls can fail, sending all those tons of toxic waste spilling into the surrounding environment.

In Gallatin, that surrounding environment includes the Cumberland River and, just two miles down Steam Plant Road, a cluster of homes.

Some of those homes draw their drinking water from private wells. Albert Hudson is a homeowner who does that, and in late 2015, according to reports at the time, the Tennessee Department of Environmental Conservation notified Hudson that tests had detected hexavalent chromium, a chemical that is found in coal ash and can be harmful to humans at high enough levels, in his water. TDEC told Hudson that his well water met standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency, but that the level of hexavalent chromium present in the water was “slightly” above the EPA’s risk levels. He started using bottled water.

Hudson declined to speak to the Scene for this story, as did his attorneys, who said he has grown weary of the media attention that has come his way since the state found something in his water. But the condition of nearby well water is not the only concern surrounding the plant.

Conservation groups represented by the Southern Environmental Law Center are suing the TVA in federal court, alleging that it has violated the federal Clean Water Act by allowing coal ash to seep into the groundwater and flow into the Cumberland River, bringing with it thousands of pounds of toxins such as arsenic and cadmium. In preparation for the case, they say, experts and attorneys used TVA data to estimate that more than 27 billion gallons of coal ash have leaked from the facility since it opened in the 1950s. The trial, the first of its kind in Tennessee, is set to begin later this month.

SELC attorneys suggest that TVA’s handling of coal ash at the Gallatin site, among others, could lead to catastrophe in the future. But what has already occurred, they say, is a “hidden environmental disaster.”

Tennesseans are more familiar with coal ash than most.

On Dec. 22, 2008, at around 1 a.m., the retaining wall of an 80-acre ash pond at the Kingston Fossil Plant 40 miles west of Knoxville collapsed, sending 50 years of waste spilling out into the night. In all, 1.1 billion gallons of wet coal ash rushed forth from the plant — a tidal wave of toxic sludge that covered some 300 acres, spilled into the nearby river and destroyed three homes, sweeping at least one off its foundation. It is the worst coal-ash spill in American history.

Speaking to the Scene last week about changes made to coal-ash disposal practices since the Kingston spill and environmental concerns surrounding the Gallatin plant, TVA spokesman Scott Brooks claimed a silver lining. Citing a recent announcement from the EPA, Brooks says that after the six-year, $1.1 billion cleanup effort, the ecosystem surrounding the Kingston plant has returned to pre-spill conditions.

“It’s certainly encouraging that at Kingston, something that happened that shouldn’t have happened in 2008 has not had a lasting impact on the overall ecology,” Brooks says. “And that’s a good example of what can happen, because out at Kingston there is roughly 500,000 cubic yards of ash from that spill at the bottom of the Emory River, and yet it still has had no impact on the ecology.”

Brooks’ statement is in line with the generally upbeat and confident tone TVA officials use in the face of concerns about their operations.

But the TVA has made changes since the Kingston spill which they say are aimed at preventing seepage or another spill. In 2009, the TVA committed to a change from wet coal-ash storage to dry storage at a cost of $1.5 to $2 billion. Removing water from the process, Brooks says, addresses one of the main concerns when it comes to ash escaping the ponds and reduces the possibility of a collapse like the one at Kingston, where the earthen dike holding back more than a billion gallons of coal ash liquified. (The TVA has also taken a number of steps to reduce emissions and improve air quality around their plants.)

“We want to be able to say for certain that nothing like Kingston can happen again,” Brooks says.

The Gallatin plant began using a dry-storage landfill for coal-ash disposal last year, and as a result there will be no wet storage of coal ash going forward. But the old ash ponds will remain, covered with a liner and “capped in place,” according to industry parlance. The TVA says it regularly performs maintenance inspections on the ponds and that the earthen dikes “have been thoroughly evaluated, and there are no issues with the stability or integrity of the plant’s current ash ponds.”

But according to the SELC, which is suing the TVA on behalf of the Tennessee Clean Water Network and the Tennessee Scenic Rivers Association, these measures come too late to address the harm done by decades of violations and the resulting pollution from the plant, and they don’t go far enough to prevent such damage in the future.

From above, the plant’s relatively close location to private drinking wells (circled) is apparent.

Part of the problem, says the SELC, is something they don’t blame on the current leadership of the TVA. But the peninsula on a bend of the Cumberland River, they say, is simply a terrible place for a coal-fired power plant, situated over “karst topography” with sinking streams, shallow bedrock and sinkholes. The TVA quibbles with the SELC’s assessment of some of the area’s features, particularly the prevalence of sinkholes around the plant’s ash-disposal ponds.

The proximity of the plant to the river, Brooks says, is a common one.

“Plants in general — whether they’re coal plants, gas plants, nuclear plants — are almost always going to be located near bodies of water, because you need a stream of water, a source of water for operation and for cooling,” he says.

The SELC would like to see the TVA go a step further than abandoning the wet storage of coal ash in what they see as a precarious area. They want to see the TVA excavate their coal-ash pits and move the waste to more modern lined landfills. They point to several utilities in the Southeast, like Duke Energy and Santee Cooper, who have agreed to do just that, at great cost.

“Our preference is to store the coal ash on TVA property so that we can be sure it’s behaving the way it’s supposed to, so that it stays where it’s supposed to be,” says Brooks. “We monitor it to make sure nothing is changing. We keep it on TVA property rather than making it someone else’s problem.”

And that’s just what these environmental groups are concerned about, really: that this old coal ash will eventually become, and in a sense already is, everyone else’s problem. In a post on the SELC website, the group quotes from a report filed in court by Dr. Chris Groves of Western Kentucky, who will serve as an expert in the lawsuit. He sums up their concern about the old coal ash and the land it’s sitting on.

“The bottom of the ash pond is not like a liner, it is more like a colander,” Groves writes.

Brooks dismisses some of the group’s more dramatic claims as “scare tactics,” insisting that testing by the TVA on its property shows nothing toxic is leaving its property. But the SELC maintains that every day the plant is open represents another day of a slow-motion disaster.

“The Kingston disaster is on people’s minds this time of year, and rightly so,” says Beth Alexander, senior attorney with the SELC’s Nashville office, in a post on the group’s site. “The Kingston failure happened in an instant. But the Gallatin failure has unfolded over years, out of sight. With [the Deepwater Horizon oil spill], there was an underwater camera, and we all saw the tragic oil spill as it happened. At Gallatin, there’s no camera to record it, but the contamination is happening every day.”

Lawyers will finally step into Judge Waverly Crenshaw’s federal court next week for pretrial motions, more than two-and-a-half years after the two conservation groups began their legal campaign. Using the Clean Water Act, the landmark piece of environmental legislation designed to stop pollution into the nation’s rivers, streams and groundwater supplies, they filed suit under provisions which allow citizens to step in when state and federal governments aren’t living up to their end of the law.

On Nov. 10, 2014, the Tennessee Clean Water Network and the Tennessee Scenic Rivers Association issued a 60-day “notice of violation,” which started a legal clock: TDEC or the EPA could step in and take up the allegations of pollution, or leave it to the courts. Just under the wire, on day 57, TDEC filed its own narrower suit in chancery court. The timing raised more than a few eyebrows among environmental groups: Under Gov. Bill Haslam, TDEC has been seen as fairly toothless, often seeking to partner with polluters rather than drop a hammer of enforcement. Add to that the public comments of current TDEC commissioner (and former TVA legal counsel) Robert Martineau that TVA “would rather be dealing with us than a federal judge,” and a cynic could be forgiven for believing the fix was in.

But Crenshaw allowed the federal suit to continue, writing in a September 2016 ruling that the limited scope of the state’s action made the conservationists’ legal course necessary. At issue are the toxic seeps from ash ponds.

“TVA’s monitoring wells have shown that the groundwater under and around the Ash Pond Complex is contaminated by a number of metals and other pollutants, including aluminum, cobalt, iron, manganese and sulfate, which are present in concentrations above state and federal standards,” the suit says. “These unpermitted discharges, or ‘seeps,’ consist of contaminants that leak … directly into the Cumberland River.”

Tests by both the TVA and independent labs indicate levels of arsenic, cadmium, selenium and other toxic agents harmful to both humans and the wildlife in the Cumberland River and Old Hickory Lake further downstream. The TVA and the conservation groups will spend days in court arguing over the impact and scope of the pollution, but one glance through an expert’s presentation of the effect on wildlife — picture deformed fish, their spines permanently in an “S” shape due to selenium-induced scoliosis — and even the casual viewer begins to understand the power of these chemicals to alter a natural environment.

“Other utilities are moving coal ash from pits like these into dry, lined storage, where it can’t contaminate groundwater anymore,” Alexander says. “As a government agency, TVA should do more than the absolute minimum to protect Tennessee’s water and communities. And citizens shouldn’t have to sue TVA to make that happen. TVA should recognize that Tennessee will never be able to move forward to a cleaner future unless TVA responsibly handles this decades-old legacy of coal-ash waste. Tennesseans deserve better.”

This action and the ongoing state suit may bring TVA into compliance, but the the concerns of environmentalists aren’t simply at the ground, or water, level. Congress’ refusal to confirm President Barack Obama’s renomination of three TVA board members to second terms on the utility’s governing body means President-elect Donald Trump will have the chance to significantly alter the makeup of the board. For those who would guard the state’s resources against man-made harms, this suit may be a glimpse at what the next few years of environmental protection look like.

When it comes to the most critical question, the TVA insists that there is no cause for concern. Brooks says the TVA can say “without hesitation” that there has never been an impact to drinking water at the Gallatin site or any other facility.

“We’ve been doing monitoring and sending data to the state for decades, making sure what is on TVA property stays on TVA property,” he says. “We monitor for dozens of different potential contaminants before anything leaves the site. We have discharge permits that we send our water once it’s been filtered and cleaned back into the river, and we can tell exactly what’s going back into the river and everything is within our permit standards. And then it would have to travel in a massive water supply down river and then get through all of the treatments and everything at the municipal intake before it would get into the water. So there are numerous layers of safeguards to make sure what’s going on on TVA property does not impact drinking water.”

Still, remember Albert Hudson? In October 2015, in the same round of testing that turned up hexavalent chromium in his private well water, the state found low levels of the chemical in the river near the municipal intake for the city of Gallatin. If the image of Julia Roberts climbing down a well is coming to mind, there’s a reason: Hexavalent chromium was the contaminant at the center of the water contamination case led by Erin Brockovich — played by Roberts in the Steven Soderbergh-directed film — in the early 1990s.

In 2015, Gallatin city officials said they had not detected anything in the city’s water supply. But the intake isn’t far down the river.

Drive back down Steam Plant Road away from the Gallatin plant, taking a left on Odom’s Bend Road and heading straight on until you run into Water Avenue. There, across the street — nearly five miles by road, but much closer as the river runs — is the Gallatin Water Plant, the site where water from the Cumberland is collected to be used as drinking water for the city.

Standing in the parking lot, as the river laps up against the bank, one can look off to the southeast and see the two towering stacks of the Gallatin Fossil Plant, looming over the trees and looking down on the water.