Riverbend Maximum Security Institution

When you’re speaking to someone in prison over the phone and your time is nearly up, an automated voice will break into the conversation: You have one minute remaining.

If the casual nature of a phone call has lulled you into forgetting, this emotionless voice will remind you that the person on the other end of the line is locked away. The pinhole through which this person’s voice can be heard by the outside world will soon close. When the minute is up, the call will be abruptly disconnected.

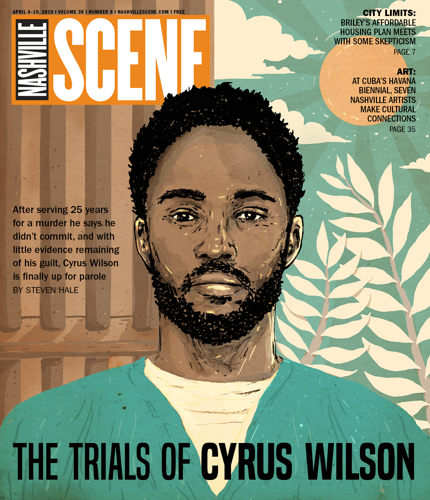

When that voice breaks into my conversation with Cyrus Wilson, he is talking — from Riverbend Maximum Security Institution in Nashville — about what he wants to express at his April 17 parole hearing.

“For me,” he says, “I think the thing that’s going to be most important is at least conveying to them that not only am I prepared to be a productive citizen when I come home, but also I would like be able to convey to them ... or question, ‘Why would they leave me here?’ Like, ultimately what would it do? What good would it do for me to continue my incarceration considering my jacket [criminal file] and who I am? There’s no reason for me to be here.”

Wilson won’t be the first person to tell a parole board that they should be released from prison. But for Wilson that statement carries extra weight. Now 44, he has been incarcerated for 25 years for a crime that he has always insisted he did not commit.

Cyrus Wilson and his wife Casey

Wilson has been saying he didn’t kill Christopher Luckett since he was arrested for the Edgehill murder in September 1992.

He met his wife Casey, to whom he has now been married for five years, through a friend during a jailhouse phone call months after his arrest. He was 18, she was a year younger. And when she asked why he was in jail, he told her he’d been arrested for a murder. But it was OK, he said. He was innocent and his attorneys were working on it.

The case went to trial in February 1994. The prosecution’s case relied on circumstantial evidence — Wilson had reported to police two months earlier that Luckett had stolen his car — and the testimony of juvenile witnesses. In particular, two boys — then 16 and 14 years old — timidly testified that they saw Wilson chase Luckett with a shotgun and shoot him from close range as Luckett tried to escape by crawling under a chain link fence. But Wilson took the stand too, against the advice of his attorney at the time, and he said they were all lying.

The jury did not believe him, and Wilson was sentenced to life in prison.

But 25 years later, the case against him would seem to have fallen apart (as was the subject of “Burden of Proof,” the Oct. 26, 2017, Scene cover story). It was thin to begin with. Police did not attempt to get fingerprints off a duffel bag or shotgun shells found at the crime scene. At the trial, prosecutors didn’t even introduce a murder weapon. In fact, a Tennessee Bureau of Investigation report introduced by Wilson’s attorneys at a 2013 hearing showed the shotgun police initially believed was the murder weapon — and which the prosecution strongly suggested had been used — did not match the shells from the crime scene.

In recent years, the state’s original case against Wilson has been seriously called into question. Four of the state’s witnesses — including two supposed eyewitnesses — who were juveniles when they testified in the original trial have recanted their testimony. They say they were coerced by prosecutors and police, including then-homicide detective Bill Pridemore, who is about to finish his second term on the Metro Council. In their recantations, the witnesses tell the story of law enforcement officials who quickly zeroed in on a suspect and cut corners to see him convicted; the men say they were threatened with prosecution if they didn’t tell investigators what they wanted to hear, and were coached on what to say at trial. Furthermore, the men don’t appear have anything to gain by recanting their testimony now. (Marquis Harris and Phedrek Davis, who appeared in court to recant their testimony last year, were in prison for unrelated crimes and in no position to see their sentences reduced as a result of their recantations.)

The assistant district attorney who originally prosecuted the case has since died, but Pridemore denies allegations that he coerced the juvenile witnesses in the case.

“I’d never threaten anybody to the point of incarceration [to get them to] provide false information,” he told the Scene in 2017. He repeated his denials in court at an October 2017 hearing. (The Scene reached out to Pridemore to see if he wanted to comment for this story, but did not hear back by press time.)

Now Wilson’s case has attracted the attention of college-age activists who weren’t yet alive at the time of the arrest. And a large group of family, friends and supporters are rallying behind him, planning to show their support at his parole hearing later this month. At the same time, Wilson is still fighting his conviction in court — a fight that has resulted in repeated disappointments.

In 2008, Wilson got a hold of a note from one of the prosecutors’ files that wasn’t turned over to his defense attorneys back in 1994. The handwritten note seemed to back up what Wilson had claimed all along: that the testimony against him wasn’t credible.

“Good case but for most of [the witnesses] are juveniles who have already lied repeatedly,” it read.

Wilson argued that the note represented exculpatory evidence that had been withheld from him. But in 2012, the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled that the note was inadmissible in court and not enough to force a new trial.

Two years later, the courts rejected his appeals for a new trial based on the first two witnesses who recanted in 2013. And last May, Nashville Judge Seth Norman — who presided over Wilson’s original trial in 1994 — denied his request for a new trial based on the two other witnesses who had come forward to say they were pressured into lying. Norman essentially concluded that the juvenile testimony of Marquis Harris and Phedrek Davis in 1994 was more credible than the claims they came forward with more than 20 years later.

Now Wilson’s future depends on the outcome of two efforts proceeding on separate tracks. Before leaving her law firm to start the Tennessee Innocence Project, Nashville attorney Jessica Van Dyke prepared Wilson’s appeal, which is pending before the Court of Criminal Appeals. Meanwhile, he is finally about to be eligible for parole. He and his supporters are of course hoping the parole board will decide to grant his release. But for Wilson, going before a body that ostensibly evaluates whether a prisoner is sufficiently remorseful and reformed to rejoin society is a thorny prospect.

“One of the things that I feel very violated about the parole board is the fact that I’m going to go in front of this parole board and they’re not going to view me as a human,” says Wilson. “They’re not going to view me as a person. They’re not going to view me as someone who has a family and has kids. They’re going to view me as a criminal. At the end of the day I’m going to have to sit in front of them as a criminal and have to answer their questions to the best of my ability and vie for my freedom as a man who has never committed a crime and should never have even been here.”

Wilson in 2015

Wilson finds himself in what Northeastern University law professor Daniel Medwed has dubbed the “innocent prisoner’s dilemma.” It is generally understood that parole boards look for the prisoner appearing before them to take responsibility for their crime and express remorse. For prisoners who maintain their innocence, this presents an obvious problem.

In a 2008 article for the Iowa Law Review, Medwed writes: “The yearning to escape can overwhelm even the strongest and most stoic of people and prompt an innocent prisoner to surrender to the lure of ‘admitting’ guilt before the parole board to boost the odds of a parole grant. Yet regardless of whether that admission accomplishes its objective, inculpatory statements at parole hearings can hamper the prisoner’s later attempts to prove innocence through litigation and thus have long-term negative effects.”

For that reason, former longtime Metro Public Defender Dawn Deaner will represent Wilson at his parole hearing on April 17.

“My role is really to speak to the issue of the status of the legal proceedings in his case,” says Deaner, “the history of his case, and why he is not in a position to acknowledge or say he is guilty of something that he has always said he is not guilty of and which, at this point, there is very little evidence to suggest the state could prove he’s guilty of.”

The parole board’s role, she says, is not to make a judgment on the validity of someone’s conviction.

“So it’s really now about trying our best to protect Cyrus’ pursuit of his exoneration and refocus best that we can the discussion on why he is a good candidate for parole and why the parole board can feel comfortable releasing him into the community,” she says. “That he is not a risk, that he has a strong community here in Nashville supporting him, and it’s time for that support to pick him up and to take him on his way.”

Wilson says the criteria by which the parole board evaluates an inmate’s fitness for release is unclear to him, based on his experience watching fellow inmates go before the board. Recent data suggests Tennessee’s board is not often inclined to grant a prisoner’s release. Based on Tennessee Board of Parole records requested by the Scene, the body has held 69,031 hearings in the past five calendar years (Jan. 1, 2014, to Dec 31, 2018). Only 18,562 of those hearings resulted in a decision to grant parole — a grant rate of 26.8 percent. (State parole boards have varying degrees of authority, and state-by-state data is hard to come by. But figures from a 2016 study by Minnesota University’s Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice suggest Tennessee grants parole at a rate that falls on the lower end of the spectrum, particularly when compared to states with similar incarceration rates.)

Meanwhile, Wilson awaits another court decision on whether recent developments in the case are enough for him to get a new trial. In a brief filed in January, Van Dyke works through the long legal history of the case, arguing why the testimony of state witnesses was problematic from the beginning, and why their recantations should be seen as credible. For instance, she highlights how Marquise Harris — who was 14 when he testified that he watched from his bedroom window as Wilson shot Luckett — originally testified that he saw Wilson after the murder wearing gray sweatpants with blood on them. Despite that, she writes, “There is no indication that police ever obtained a search warrant for Wilson’s home or recovered the bloody gray pants.”

Summarizing the argument toward the end of the brief, Van Dyke bluntly states that beyond the juvenile witnesses from the original trial, “there is no other evidence that Mr. Wilson committed this murder.” In arguing that the trial court was wrong to deny Wilson a new trial last year, she highlights new information that arose during a 2017 hearing.

When he testified at that hearing, Pridemore said that a then-13-year-old Harris had indicated he would exchange information about the murder for a guarantee that he would receive Crime Stoppers reward money. That wrinkle was never mentioned at the original trial, and thus Wilson’s original defense attorneys were never able to cross-examine Harris about whether he tailored his testimony to fit what police and prosecutors were looking for so he could get the reward money.

In the brief, Van Dyke writes: “This would be much more compelling on cross than a situation where a witness comes forward, provides credible evidence, and is then given a reward without request. But here, Mr. Harris demanded the reward. At trial, Marquise Harris simply testified that Pridemore asked him for information, and he (Harris) answered his questions. Second, Mr. Harris was still a child at this time. Any reward given to a child would have had much greater significance than an adult that was able to earn money.”

Later, she concludes: “During closing arguments, defense counsel could have argued that Mr. Harris was not testifying because he was compelled by civic duty or his moral compass, but because he had one desire — a monetary reward. After weighing the cumulative evidence in this case, it is likely that that a jury would have reached a different outcome if Marquise Harris had been cross-examined on this issue.”

After spending more than half of his life in prison, Wilson says he devotes most of his energy to fighting the gravitational pull that leads many inmates to becoming institutionalized. He works out, he plays basketball. An aspiring writer, he says the books he reads are mostly about writing. He recently read Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones.

He tends to listen to upbeat old-school hip-hop as well as newer artists like Future.

“I don’t try to listen to a lot of slow music if I can help it,” he says. “Mainly because, I don’t know, I think it kind of just changes the mood and your mind state to a place where it’s just kind of depressing. And, I mean, after being incarcerated so many years, the one thing I’ve always tried to do is maintain my state of mind. It’s very difficult in prison to not get into this routine where the routine becomes a way of life.”

Wilson’s resistance is so total that he says if it weren’t for his wife sending him packages he would likely never order them for himself. Even though the prison incentivizes inmates with opportunities to order out pizza or fried chicken, he often passes on those opportunities. He says he is determined not to become someone who would kill for a piece of chicken from the outside — a notion that he says is very much a possibility at some prisons, like Trousdale Turner Correctional Center, where he has spent time over the years. He watches as other prisoners will smuggle candy from the visitation gallery back into the unit, earning large amounts of money by selling the rare treat to fellow inmates. He says he refuses to buckle against the weight of a system that seems designed to dehumanize.

And yet, he has stayed here — even shutting down plea negotiations years ago — because he is equally determined to clear his name.

“The whole reason why I’ve stayed in prison and fought my case to fight for my conviction to be completely taken off my back and to not have it be a part of my jacket and who I am is because as long as it is, I don’t care who you are, you are going to always perceive me as the criminal,” he says.

“But as long as I have this conviction on my back, I’m still a criminal. When the police pull me over, I’m going to be a criminal. If I go to an interview or if I want to have a better job than whatever job I may be in when I’m there, when they look at my jacket, I’m going to be a criminal. That is going to be how I’m viewed. My kids, when people see me at school and I have to go to a school meeting, I’m going to be a criminal. If they know my history, if they know anything about my case, if they know anything about my children that have come to visit their entire life because I’ve been in prison their entire life, I’m saying to everyone who knows me for what the system has created me to be, I am a criminal. And I’m saying, I have spent my entire incarceration trying to, as a person, not allow myself to become the criminal that they have made me out to be. It is my mission every single day here.”