In the wake of the violence at August’s white nationalist gathering in Charlottesville, Va., Confederate monuments have entered the national spotlight as Southerners, in particular, grapple with their meaning and why they were erected. It’s a debate we should be having. But this conversation has raised another question: What monuments should we be erecting? If at the heart of the debate over symbolism is an acknowledgement that these busts, statues and icons carry power in addition to just memorializing history, we should actively seek new ways to honor some of the most impressive figures Nashville and Tennessee have produced. Here are 10 candidates worthy of such attention — potential monuments that could provide inspiration to anyone who sees them. —Steve Cavendish

Cornelia Fort

Cornelia Fort

Nashville’s first female military pilot, who died during WWII service

Folks seem to love statues of people who put their lives on the line. So why shouldn’t Cornelia Fort, the first U.S. female pilot to die in active duty, receive that honor?

Before getting accepted into the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron, Fort (a prominent Nashvillian and the daughter of one of the founders of National Life & Accident Insurance Co.) was the first U.S. pilot to encounter the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. She narrowly escaped colliding with the Japanese air fleet while training a civilian pilot that morning.

A year after being accepted into the WAFS in 1942 — the only service option for female pilots in an otherwise male-only air corps — Fort met her death on March 21, 1943, while flying alongside five male pilots from Long Beach, Calif., to Love Field in Dallas. She was 24 years old.

“Some of [the male pilots] began teasing her, and then they began to pretend that they were fighter pilots,” pilot Adela Riek Scharr wrote in a history of the incident. “She was easy game for them, for she had never had any evasive training in military maneuvering. By the time they got to Texas, a few of the men has become too bold and were flying too close. A joke had become harassment.” Eventually one of the male pilots, Flight Officer Frank E. Stamme, hit Fort’s plane.

“She zigged when he guessed she would have zagged, and he snagged her,” Scharr wrote.

The Cornelia Fort Airpark in East Nashville is named for her, but that’s just not enough to show how important her legacy is to Tennessee. —Amanda Haggard

Correction: The above anecdote, from a previous Nashville Scene story in 1996, has since been disproven. The writer of that story, Rob Simbeck, gave the following update as to how Fort died: “During my research for Daughter of the Air (1999, Atlantic Monthly Press), I learned that Adela Scharr ... and many others simply passed along a rumor. I spoke with two of the six (not five) male pilots on that flight with Cornelia, studied the official reports and otherwise gathered as much primary information as I could. Cornelia and Stamme were flying wingtip to wingtip (as the others had been), something that was forbidden but that pilots did anyway as a means of learning news skills. One of them did something stupid for a quarter of a second and Cornelia crashed, apparently unconscious from the moment of impact.”

Diane Nash (center) protests in the 1960s

Diane Nash

A Freedom Rider and civil rights pioneer

Diane Nash wasn’t born in Nashville, but she did some of her most important work while living in the city as a student at Fisk University — and she’s the perfect example of someone who deserves a statue while she’s still alive to witness the honor.

After attending nonviolence seminars taught by the Rev. James Lawson — who was booted from Vanderbilt University for his civil rights work — Nash helped lead sit-ins that helped bring about integration at lunch counters in the city. It wasn’t just the sit-ins and protests, but also conversations she had with then-Mayor Ben West that pushed Nashville to become the first city in the South to desegregate lunch counters in 1960.

Nash was a co-founder and leader of the influential Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and she helped organize and participated in the Freedom Rides. Even when a bus was burned during the protest rides through Alabama, Nash insisted that the rides move on throughout the South.

“It was clear to me that if we allowed the Freedom Rides to stop at that point, just after so much violence had been inflicted,” Nash says in the PBS documentary Freedom Riders, “the message would have been sent that all you have to do to stop a nonviolent campaign is inflict massive violence.”

Her organizing went beyond Nashville, including work on the Selma voting rights campaign of 1965, but there’s no doubt that Nash deserves recognition for all she did for the city. —Amanda Haggard

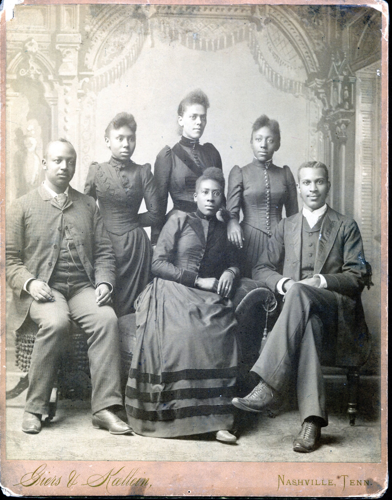

Fisk Jubilee Singers

This is what freedom sounds like

Plenty of musical origin stories have become legend in Nashville, but few are as worthy of being literally set in stone as that of the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Five years after Fisk University opened in 1866, with a student body largely made up of black men and women who’d recently been freed from slavery, the Jubilee Singers were formed with a mission — to tour and sing, with the hope of raising enough money to keep the university’s doors open. They are said to have toured the route of the old Underground Railroad, and an account of their history on the university’s website notes the curiosity they aroused among white audiences by eschewing the racist “minstrel fashion” of performing that audiences were used to. By the end of 1872, the group had been invited by President Ulysses S. Grant to sing at the White House.

One of the earliest known recordings of the Jubilee Singers, from 1909, features them performing “Swing Low Sweet Chariot.” Try to suppress the chills as their swelling, harmonizing voices sing words that had been the coded message of hope for enslaved African-Americans across the South only decades earlier. The Jubilee Singers represent not just a group of black men and women claiming the right to perform as talented artists — rather than jesters for white masters — but also the unfathomable courage it must have taken to do so when many white Americans would have happily seen them put back in chains, or at least relegated to second-class citizenship forever. The fact that they did this in support of an institution like Fisk makes them all the more worthy of honor. The group performed for Queen Victoria in 1873, and it’s said that during their visit the queen dubbed Nashville “Music City” — whether or not that part of the story is true, the singers’ origin and perseverance are virtues that Music City should be proud of. The fact that the Jubilee Singers continue to exist today serves as a living memorial to their history, but Nashville should erect one in stone as well. —Steven Hale

Anne Dallas Dudley

Anne Dallas Dudley

Because a woman this important can’t have enough notice

A little more than a century before some 15,000 people filled the streets of Nashville for a Women’s March following the inauguration of President Donald Trump, dozens of vehicles adorned with yellow banners paraded from the state Capitol to Centennial Park. That march — which took place May 2, 1914 — was also made up largely of women. They were demanding the right to vote, and their gathering was organized by Anne Dallas Dudley.

When the parade arrived at Centennial Park, Dudley delivered a passionate speech to the thousands assembled there in what is said to have been the first outdoor speech given by a woman in Nashville. In a 2014 column calling for a street to be named in Dudley’s honor, Nashville historian David Ewing quoted her as having told the crowd that “every reform is started by a minority.” Capitol Boulevard was officially renamed for Dudley earlier this year, and there’s even an apartment complex, The Dallas on Elliston, named after her as well.

But a Nashville woman who became a national leader in the movement for women’s suffrage deserves more than a street and a Midtown apartment building. A monument honoring local suffragettes was unveiled in Centennial Park in 2015, but given that the town is littered with statues, streets and schools honoring Andrew Jackson — not to mention two hunks of metal honoring Nathan Bedford Forrest — we can certainly make room for another in honor of Anne Dallas Dudley. —Steven Hale

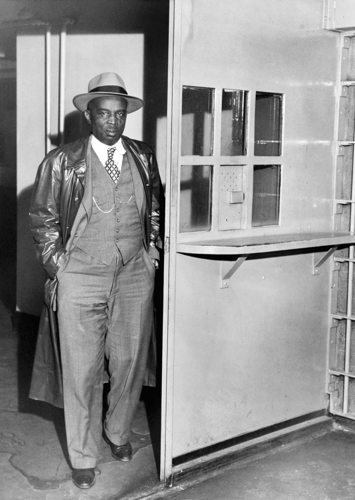

Z. Alexander Looby in November 1950

Z. Alexander Looby

A civil rights icon who became the target of racist bombers

Z. Alexander Looby’s origin story is shockingly Hamiltonian. As a teenager, the orphaned Looby moved on his own from Antigua to the United States, where he attended Howard University, Columbia University and New York University.

But most of Looby’s statue-worthy achievements came after he moved to Nashville to work as a professor at Fisk University. Alongside Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP, he successfully defended a group of black men charged with attempted murder after race riots in Columbia, Tenn. He was elected to the Nashville City Council in 1951 alongside Robert Lillard, the first black members elected in 40 years. After Brown v. Board of Education, he filed a desegregation lawsuit in Nashville, which is in part credited with school desegregation in the city. He is also recognized for helping end segregation at Nashville’s public golf courses and in the airport’s dining room.

Another moment from his illustrious career was less directly responsible for a major milestone in Nashville’s civil rights history. Looby was supporting and defending students involved in Nashville’s sit-in protests in 1960, when on the morning of April 19, segregationists bombed his house near Meharry Medical College. The home was mostly destroyed, but neither Looby nor his wife Grafta was injured, as they slept in the rear of the house.

That same day, students from Fisk University, including Diane Nash (see above), led a silent march to city hall, where the now-famous confrontation between the protesters and Mayor Ben West took place.

“Do you feel it is wrong to discriminate against a person solely on the basis of their race or color?” Nash asked West. West said yes, Nashville’s lunch counters were desegregated shortly after, and Looby helped gain dismissals for dozens of student protesters charged with “conspiracy to disrupt trade and commerce.”

Looby has a library and the city’s Looby Theater named for him, but a statue of Nashville’s answer to Alexander Hamilton might make a fitting addition to local historical honors. It might inspire a writer to pen an appropriate musical, too. —Stephen Elliott

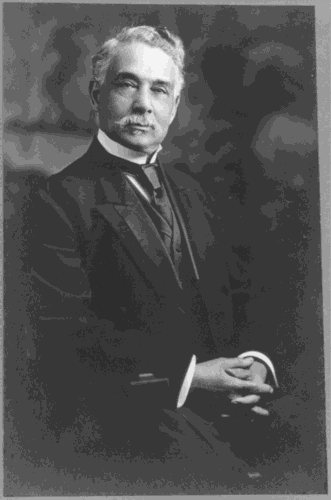

James Carroll Napier

James Carroll Napier

From the council to treasury to banking, a titan of the city

James Carroll Napier, like his aforementioned successor in the Nashville bar Z. Alexander Looby, was a prominent black Republican and a member of the Nashville City Council (the first African-American member elected to that body). Though we’re here to discuss Napier’s qualifications for a commemorative statue, he is probably better known for his signature than his physical appearance (which featured an epic mustache).

As Register of the Treasury during William Howard Taft’s administration, Napier’s signature appeared on most American currency printed during his two-year tenure. He resigned from that position after the Wilson administration instituted segregation practices for federal employees.

Napier was born to slaves, and his achievements on behalf of Nashville are many, some of them well-known — enough to get his name on an elementary school, a park and a housing development in the city. He led protests to encourage the city to hire black teachers and desegregate streetcars. He was an ardent supporter of Fisk, Tennessee State and Meharry universities.

He helped start the One-Cent Savings Bank and Trust Co., in part to encourage economic growth in the black community. That bank still exists, now called Citizens Savings Bank and Trust Company.

During Napier’s 95 years, he fought against lynchings, segregation and injustice, and for the education and economic progress of black people. When he died in 1940, the fight for civil rights was not over, but his successors had one more standard-bearer on whom to base their continued efforts. —Stephen Elliott

Ida B. Wells

Ida B. Wells

A tireless fighter for civil rights and suffrage

Ida B. Wells’ list of accomplishments is long. She worked tirelessly for civil rights and women’s rights, including suffrage. She ran newspapers and toured the world. While she was the editor of Memphis paper Free Speech and Headlight, three of her friends were lynched. As a result, she began to examine lynching cases throughout the South. Though lynchings were often purported to be in response to black men raping white women, Wells discovered this wasn’t the case — lynchings were a method of social control designed to punish black people for not deferring to white people in some way.

In the early 1890s, Wells wrote a series of editorials about the truth behind lynchings and a pamphlet outlining her discoveries called “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” The Commercial Appeal, at the time headed by Edward Carmack, called for violence against Wells. In 1892, a white mob destroyed Free Speech and Headlight, and Wells moved to Chicago for her safety.

Wells is one of the most important people to ever live in Tennessee; she almost single-handedly changed perceptions outside the South of lynching. She was one of the founders of the NAACP and is closely connected to two historic black colleges in Tennessee — she attended Fisk and Lemoyne-Owen.

And whose statue do we have at the state Capitol? Edward Carmack — the man best remembered, if he’s remembered at all, for getting shot and for being Wells’ enemy. A fitting monument to Wells might be to leave the Carmack statue in place, but put a larger statue of Wells right next to it, so she is properly recognized for the giant she is — and he is forever in her shadow. —Betsy Phillips

DeFord Bailey

DeFord Bailey

A country music star in spite of the odds against him

It always seems like DeFord Bailey is just about to finally get his due. He had a smart book written about him, Deford Bailey: A Black Star in Early Country Music by Dave Morton and Charles Wolfe. There was a lovely PBS documentary about him. In 2005, he finally made it into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

And still, none of these things seems to have secured Bailey’s place as one of the early legends of the genre in the minds of country music fans. When Opry announcer Judge Hay explained away Bailey in the 1940s as a kind of pitiable “mascot” of the Grand Ole Opry, he doomed Bailey to never achieving the permanent fame he deserves.

Let’s go through some of his accomplishments: He was one of country music’s first radio stars, first at WDAD and later at WSM; he was the first star to appear on the Grand Ole Opry, since he was the guy playing when Judge Hay coined the term “Grand Ole Opry”; when Ralph Peer came to Nashville to make the first commercial recordings in town, Bailey played on one of those sessions; he was one of the Opry’s highest-paid stars and a huge draw when Opry stars went on the road. Legend has it that an up-and-coming Roy Acuff — who has a statue at the Ryman — was paired with Bailey on tour so Acuff could get the attention of Bailey’s huge crowds.

Bailey invented being a country star, from having a good radio presence to appearing on the Opry to demonstrating the importance of touring, to, sadly, being forgotten when you’ve fallen out of fashion. The least we owe him is a monument, a place where people can pay tribute to a man who literally made this city, as it is right now, possible. —Betsy Phillips

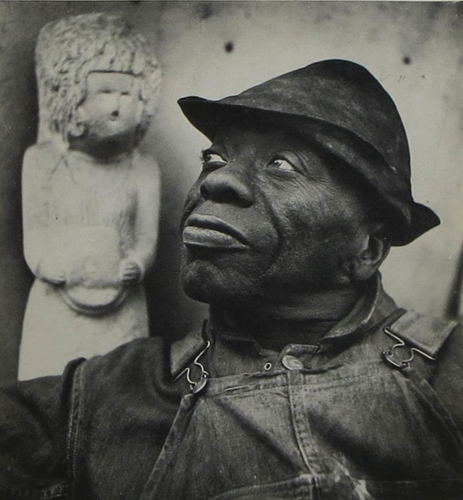

William Edmondson

William Edmondson

Nashville’s greatest sculptor even left us a guide

The idea that a celebrated sculptor who rose to international fame by making stone figures could be buried somewhere without a tombstone is the kind of heartbreaking irony usually reserved for jokes about depressed clowns. But William Edmondson is Nashville’s most famous artist, and his unmarked grave is somewhere in Mount Ararat Cemetery. Edmondson’s legacy is far from forgotten — Cheekwood has an extensive archive of his sculptures, and there’s a public park named after him that houses grand sculptures by acclaimed outsider artists Lonnie Holley and Thornton Dial, both of whom have called Edmondson a kindred spirit. Still, the Nashville-born artist’s story is worthy of numerous commemorations, and no wish list of public monuments would be complete without his name.

Edmondson was the son of two former slaves, and he started making sculptures after, he said, the voice of God commanded him to. Just a few years later, in 1937, he had a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art — he was the first African-American artist to have a show there. His stout limestone figures were lauded by art-world insiders like MoMA director Alfred H. Barr Jr. and Harper’s Bazaar fashion photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe. Despite Edmondson’s fame, his work never commanded significant sums in his lifetime. But times have changed, and in 2016, his “Boxer” established a new world record — both for the artist and for any work of outsider art — when it sold at Christie’s for $785,000.

If we’re looking for ideas about how to construct Edmondson’s monument, the artist himself left us with a pretty handy guide to methods from his own practice: He frequently worked with a sledgehammer and improvised tools fashioned from railway spikes, and he used limestone taken from demolished houses. —Laura Hutson-Hunter

Josephine Holloway and her granddaughter Nareda in the early 1960s.

Josephine Groves Holloway

She opened the doors for African-American Girl Scouts in Nashville

Scouting isn’t as cool these days as it once was, what with little Julia needing to balance ballet and gymnastics and soccer and guitar lessons and Chinese lessons and crafting and coding and video games and perfecting makeup contouring by age 9. But a little more than a century ago, it was a big fucking deal to even let girls play outside. And Josephine Groves knew that.

As a young black graduate of Fisk University, Groves began working to help the community at Nashville’s Bethlehem Center in 1923. Tasked with finding something for little girls to do after school, Groves decided to launch a Girl Scouts troop. Founder Juliette Low (who had started the Girl Scouts just 12 years earlier) happened to stop in Nashville in 1924 for a training session, which Groves was allowed to attend. But the troops she eventually organized were not recognized by Scout headquarters, because all the participants were black.

Groves married a co-worker, Guerney Holloway, and had to resign her job. The troops disbanded after that, until the Holloways’ daughters asked her why they couldn’t be Girl Scouts too. So Holloway started a troop up again in 1933, only to be shot down by the white Nashville matrons in charge of approving Girl Scout troops. But Holloway kept her unofficial troop going anyway. In 1942, the Scout council finally recognized the troop as Nashville’s first black Girl Scout troop. The next year, they hired Holloway as a field adviser (but still kept her office in a separate building).

Holloway wasn’t done. If the white girls got to go to summer camp, then her Scouts deserved a camp too. In 1951, she convinced her husband (by then a medical doctor) to buy 21 acres in Robertson County, and thus Camp Holloway was born. The camp began accepting white Girl Scout campers in 1963. It was one of the first summer camps in the South to include both black and white campers.

Girl Scout cookies are delicious, sure, but isn’t a 20-year fight to get black girls recognized as official Girl Scouts and another 20-year fight to integrate the Scouts in Nashville even more worthy of recognition? —Cari Wade Gervin

Photo illustration of Josephine Groves Holloway