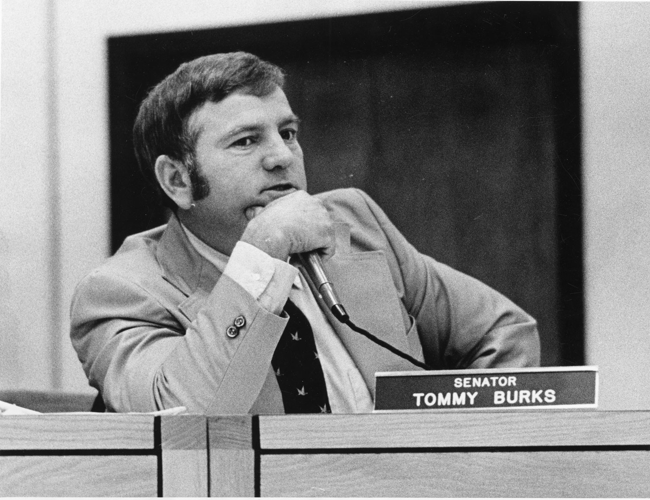

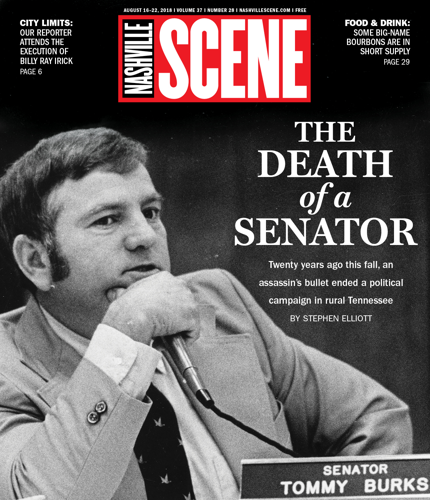

State Sen. Tommy Burks in a legislative session on Jan. 29, 1992

State Sen. Tommy Burks was preparing for some nursery school children to visit the pumpkin patch on his farm outside Monterey, Tenn., when he was shot once in the head.

According to a newspaper reporter who trekked to the scene, the hog, tobacco and cattle farm — located 90 miles east of Nashville on the Cumberland Plateau — was covered by “layers of dirty gray fog” that October morning, 20 years ago this fall.

The story made the front page of The Tennessean the next day (“Senator gunned down; Officers tight-lipped about Burks’ killing”) and for eight days to come, but it was tucked in a single column along the right edge. Most of the page was consumed by Phil Bredesen. The Nashville mayor had announced the same day as Burks’ death, Oct. 19, 1998, that he would not seek a third term.

Twenty years later, Bredesen remains on front pages as he runs for U.S. Senate. Burks, who spent 20 years as a state senator after eight as a state representative, does not, and neither does his killer.

Byron Looper had always been ambitious, though his grand schemes often fizzled out.

He entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point as part of the class of 1987, but he left before graduating. He was later elected president of the Young Democrats of Georgia, but he was asked to resign halfway through his term, according to one member of the group who encouraged him to resign. In his early 20s, he unsuccessfully challenged a popular incumbent in the Georgia House of Representatives after a short time as an aide at the legislature.

“I’ve been around politics a long time, and politics does attract a lot of unusual characters,” says Doug Teper, a former member of the Georgia House who knew Looper when the young aide worked at the legislature. “I’ll include myself in that. Tennessee’s probably the same way. We’ve had a long line of really unusual characters in Georgia politics. Then you’ve got this guy, Byron Looper.”

Teper remembers getting a call from Looper at 3 or 4 one morning after Looper had moved on from the legislature. Looper called to talk about a lawsuit he’d filed against a law school in Puerto Rico. He was suing the school because, Teper says, it wouldn’t teach one of Looper’s classes in English.

“You’re suing a law school?” Teper remembers asking. “This is not going to have a good end.”

One newspaper report suggests Looper ultimately settled the lawsuit for a small sum. But he was far from finished picking fights with powerful enemies.

In the early 1990s, Looper returned to Putnam County, Tenn., where he was born, and quickly sought once again to win political power. He ran for the state House and lost, but he was finally successful in 1996 when he was elected Putnam County property assessor, this time running as a Republican. His tenure in the county office, like his time at West Point and leading the Young Democrats of Georgia, would be cut short.

“He came here to Cookeville and started immediately running for things,” says Mary Jo Denton, a retired reporter who spent nearly four decades at Cookeville’s Herald-Citizen. “He went to court and legally changed his name to ‘(Low Tax) Looper’ and promised that he would lower the taxes. In reality, the tax assessor does not set the tax rate. But anyway, he started big public quarrels with almost every other office holder in the county for no reason that anybody could see.”

Looper, with his new middle name (Low Tax) — yes, parentheses included — promised to break up what he called the “good ol’ boy network” of Putnam County. The sheriff, the district attorney and the county commission, among others, were in cahoots, he would say. He promised, as an elected official, to expose corruption in the rural county.

“He was outlandish,” says Denton.

As property assessor, Looper compiled a list of some 400 media outlets around the state, to which he’d send press releases about his quixotic quest to upend the good ol’ boy network in Putnam County.

The year of Burks’ death had been a busy one for Looper. In March, he was indicted on charges of misusing his public office. Over the summer he mounted an unsuccessful Republican campaign for U.S. House. But he hedged his bet, and on the same August day he came in third in the congressional primary, the former Democrat won the Republican primary for the right to face Burks, the popular farmer and Democratic legislator who had represented the area in the House of Representatives and state Senate for nearly 30 years.

Though in the years ahead, the rural area would undergo a rapid shift from Democratic to Republican rule, Looper faced seemingly insurmountable odds against Burks in November.

The election would end with one candidate dead and the other behind bars, charged with the murder.

Prior to his death in 1998, Tommy Burks was well-liked by many on Capitol Hill, in spite of his sometimes divisive legislative efforts.

A late example of the increasingly endangered category of conservative Democrat, Burks introduced bills year after year with the goal of eliminating or greatly restricting access to abortions in Tennessee, a mantle taken up by Burks’ Republican successors to this day. On one such occasion, Burks sponsored a 1991 bill that would have criminalized abortions except when performed to save the life of the mother. The legislation was derailed after the state attorney general said it would violate the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade ruling — a debate still being waged decades later on Capitol Hill.

Burks also pushed for a law that would have required first-time DUI offenders to pick up trash on the side of the road wearing orange vests emblazoned with the words “I AM A DRUNK DRIVER.” Two years before his death, he urged passage of a law that would have allowed Tennessee school districts to fire teachers who taught evolution. Burks’ papers, held in an archive at Tennessee Tech, include more than a dozen books about creationism (one is titled The Lie: Evolution). He represented the district neighboring that of Dayton, Tenn., the site of the infamous Scopes Monkey Trial nearly a century ago.

For all his strong, even inflammatory opinions, multiple people who knew Burks describe him as “the salt of the earth.”

“He may have disagreed with you on the issues, but he was never disagreeable about it,” says Ken Renner, who interacted with Burks as a newspaper reporter on Capitol Hill and later as communications director for Gov. Ned Ray McWherter. “He was always nice and respectful to people and expected that from other people as well.”

When the legislature was in session, Renner remembers, Burks would wake up, feed his hogs, milk his cows and complete other work on the farm before making the nearly 100-mile drive from Monterey to the state Capitol. There he would spend the day at committee meetings and attending to other legislative business before making the same drive back home at night.

Burks’ daughter Kelly Tayes recalls one particularly nasty snowstorm. Her father’s legislative colleagues were taking bets on whether he would make it to Nashville that morning. He did.

A long stretch of Interstate 40 between Nashville and Burks’ farm is named in memory of the senator, “because he probably drove that road more than anybody,” says Tayes.

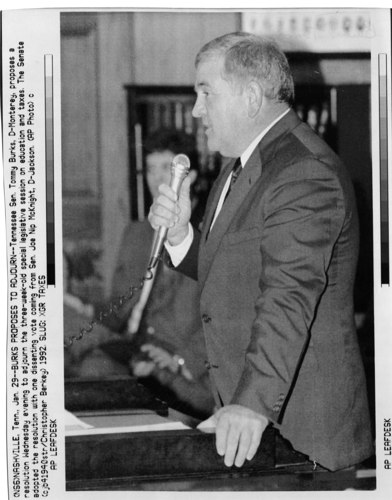

Tommy Burks, Nov. 23, 1983

On the morning of Burks’ death, District Attorney Bill Gibson was preparing to drive to Memphis with one of his assistants for an annual prosecutors conference.

“We got a call that there had been a shooting at the Burks farm,” Gibson says. “They were sketchy on details, but they believed that Tommy Burks had been shot, so we went up there — immediately left and went to the scene.”

Gibson would ultimately lead the murder trial, but in those first hours he was mostly trying to figure out what had happened. So was Denton, the newspaper reporter working the morning cops beat.

Denton heard that an ambulance and emergency vehicles were heading to Monterey, so she started checking with sources to find out where and why. Somebody at the jail told her the destination was the Burks farm, she remembers, which piqued her interest further. She ultimately got the sheriff on the phone. He told her Burks had been shot.

“It was a total shock to me and everybody else,” says Denton. “This was 10, 10:30 in the morning, and we were an afternoon paper where deadline was 12 o’clock, so I was trying to confirm everything as fast as possible. … I knew that somebody drove onto Tommy Burks’ farm and shot and killed him. I didn’t know much else.”

Looper was nowhere to be found. In the final weeks of what he had made a contentious election, he didn’t put out a public statement or offer his condolences to his slain opponent’s family. Though law enforcement officials did not make public their desire to question Looper about Burks’ shooting until three days after the senator’s death, speculation in town about the incident centered on the trouble-making politician.

There was one main witness the morning of Burks’ death: a young farmhand who told authorities he had seen a man driving away from Burks. The man was in a black sedan, the witness recalled, heading down the farm road toward the highway. The farmhand later discovered Burks slumped over the steering wheel of his truck. Working with a sketch artist the afternoon of Burks’ death, the young man provided an image that looked “exactly like Byron Looper” — at least according to Gibson, the district attorney.

Later, the farmhand saw a television news report about the campaign, which showed photographs of both Burks and Looper. The young man identified Looper as the man he had seen driving on the farm.

Investigators got another tip when Joe Bond, who’d known Looper in high school, called to tell them that Looper had confessed to the crime. According to Bond, Looper showed up at his Hot Springs, Ark., home several months before the killing and told him that he was running for political office and planned to kill his opponent. Bond, a Marine sergeant, said Looper asked for advice on how to commit the crime, but Bond didn’t take him seriously. Looper showed up again shortly after Burks’ death, Bond told authorities, and claimed he had indeed killed his opponent. Again, Bond said he didn’t take Looper seriously — at least until he saw a news report about the killing and decided to call the police.

According to authorities, Looper made his way around the South, from Bond’s home in Arkansas to Georgia before returning to his Cookeville home in the middle of the night five days after the killing. Police officers were waiting for him and calmly apprehended him.

If Looper had committed the crime, he had done so in a way that, at least on paper, benefited his campaign for state Senate. State law provided that Burks’ name would be stripped from the ballot, though it was too late for anyone else to be added, leaving just Looper’s name for voters.

“We do what the law tells us to do,” state election coordinator Brooks Thompson told reporters in the days before the election. “Nobody is happy with [the] fact that it now appears that the man killed had to have his name removed from the ballot, and the person who very well may have been involved in the killing is going to stay on the ballot.”

State Sen. Charlotte Burks

Democrats did not plan on letting Looper walk away with a victory while he sat behind bars for murder. Even before Looper was arrested, they started looking for a write-in candidate. Charlotte Burks, Tommy’s widow, decided to run. The announcement was made immediately after her husband’s funeral, attended by governors, legislators and other political luminaries. Even the Putnam County Republican Party endorsed Charlotte Burks over their nominee.

Two weeks after her husband’s death, the widow garnered more than 90 percent of the votes in what multiple reports say was Tennessee’s first successful state Senate write-in campaign. Looper, from behind bars, still mustered more than 1,000 votes, though some early votes were cast before Tommy Burks’ death.

Charlotte Burks ended up serving in the state Senate until 2014.

“She did not grieve until four years ago, when she went home,” says Tayes, her daughter. “She didn’t have time.”

It took more than a year for Looper to go to trial, a period in which he ran through a quick succession of lawyers. The two defense attorneys who ultimately took the case to trial — McCracken Poston and Ron Cordova — say at least a half-dozen others came before them.

Poston and Cordova were both former Democratic state legislators, Cordova in California and Poston in Georgia, where the latter had briefly known Looper as a young legislative aide. Though both maintain to this day that they hold some doubt that Looper committed the murder in the way that prosecutors argued — if at all — they agree that Looper, with just enough legal training to stir up problems, was a challenging client.

“All I deal with is what’s presented, and did they eliminate all reasonable doubt?” says Poston. “I’m not sure they did, although Byron seemed to do everything in his power to help them.”

According to Poston, Looper kept information from his defense team, a move he calls a “recipe for disaster.”

Cordova, nearly two decades after the trial, suggests an alternate theory of the crime (while emphasizing that he cannot prove it). He says Looper, a sort of bumbling figure, would have been unable to effectively fire the single 9 mm shot that killed Burks from two feet away.

“The conclusion I came to after my analysis is that Byron Looper enlisted Joe Bond to kill Sen. Burks,” Cordova says.

The defense team did not suggest the specific theory at trial, though they did seek to impeach Bond as a witness. Multiple attempts to locate Bond for this story were unsuccessful.

In a motion for a new trial authored by Cordova, the attorney described Bond’s “blatant character flaws and deliberate dissembling as a witness.” According to the defense, the court had improperly barred them from presenting two witnesses to Bond’s character: one who would have testified that Bond had made an unsolicited offer to sell weapons to the handyman in his apartment complex, and another who would have testified that Bond had obstructed justice in a recent military investigation.

“He was dodgy,” Cordova recalls implying during cross-examination of Bond. “He only came forward later, when, I suggested, there was a focus of attention on him.”

But Gibson, the district attorney, says “there was never anything” to implicate Bond. “Those trees got shook pretty hard by the defense,” he adds.

The witness saw only one man in the black sedan, Gibson says, adding that he knew of no motivation for Bond to participate in the crime.

Yes, Bond said he and Looper had discussed what sort of weapon would be best for the crime months before it occurred. But says Gibson: “[Bond] didn’t think he was helping plan a murder. He thought he was just talking B.S. with a nutcase friend of his.”

Despite Cordova and Poston’s efforts, Looper was convicted and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. The Burks family asked prosecutors not to seek the death penalty. According to Gibson, the family preferred the relative closure of a life sentence compared with the endless appeals that follow a sentence of death.

“I don’t know which I would choose,” Gibson says, musing on the two sentencing options. “If I knew I was never going to see freedom again for the rest of my life, I don’t know how much that life would be worth.”

Byron (Low Tax) Looper

Looper entered prison and drifted out of the news, though he’d occasionally mount appeals of his conviction.

A 2003 Nashville Scene oral history of Brushy Mountain State Prison described Looper as occupying “a tiny cell littered with legal papers.” According to a fellow inmate, “the well-educated and famously arrogant Looper” refused to scrub pots and pans on his first day in the prison, resulting in an extra month of kitchen duty.

He was transferred to the Morgan County Correctional Complex. There, on June 26, 2013, the 48-year-old was found unresponsive in his cell. He was pronounced dead at 11:10 a.m., roughly 15 years after Tommy Burks’ death.

An autopsy conducted the next day listed Looper’s cause of death as hypertensive and atherosclerotic cardiomyopathy — a heart event — with high levels of antidepressants a contributing cause. An incident report released days later said he had hit a pregnant prison counselor in the head just before 9 a.m., was restrained by guards “with the least amount of force necessary,” and returned to his cell, where he was found dead two hours later. Looper’s family was skeptical of the government’s explanation and sought a second autopsy.

The DeKalb County, Ga., deputy medical examiner who conducted a second autopsy at the behest of Looper’s family has not released a final report, because he still lacks witness reports and some of Looper’s medical records. But he confirms that his observations differ in some ways from those in the original report, which was provided to him by the Scene.

First, though the original report notes Looper’s hyoid bone was intact and atraumatic, the second examiner could not locate the actual bone, which is located in the neck and can show signs of damage in cases of strangulation. Second, though the original examiner measured Looper’s heart at an abnormally large 510 grams — which would lend credence to his finding that Looper died of a heart event — the second examiner’s heart measurement fell within normal bounds.

Geoffrey Smith, the second examiner, reiterates that he would need more medical records and witness statements before issuing a final determination, and suggests there might be innocuous reasons for the discrepancies he found. One potential witness was another inmate, who wrote a letter to his girlfriend on the day of Looper’s death begging her for help getting out of the Morgan County Correctional Complex. According to the letter, obtained by Poston and provided to the Scene, the inmate said he was two cells down from “some chubby white guy” when he saw guards “beat the man to death” while he was on the ground in handcuffs. Both medical examiners noted injuries consistent with handcuffs.

“I need you to get me away from this prison,” the inmate wrote. “These guards are crazy. I just seen them kill a man today.”

But Burks’ daughter wishes Looper had not died so young.

“When someone does something that heinous, the hate in your heart is bad, and you wish terrible things on people,” Tayes says. “But when he died it didn’t change anything. My daddy was still gone. … It was bad because [Looper] got the easy way out. He didn’t have to spend the rest of his life in jail and suffer.”

The years since Looper’s and Burks’ deaths have tempered some of the raw emotions around both, freeing many of those involved to speak more openly about the two. It was an unusual moment in recent history, forgotten by some, never known by others, and remembered, either with grief or morbid curiosity, by the rest.

Byron Looper (left) and his attorneys Ron Cordova (foreground) and McCracken Poston listen to the prosecution’s Aug. 14, 2000, opening statement in Looper’s trial for the murder of state Sen. Tommy Burks.

Multiple people who knew Looper and Burks could not help but view the events from 20 years ago through the lens of the current political atmosphere.

Burks’ daughter bemoans the “nastiness” of modern politics and that there are so few “honest” politicians left.

“[My father] is definitely not like any politician that is alive and in service today,” Tayes says. “Now your word means nothing. I mean, look at our president.”

Looper, says his attorney Cordova, “was a Trumpian figure in a pre-Trump environment.”

Teper, who knew Looper at the Georgia legislature, denies that Looper was a particularly Southern figure.

“There is a history of these kooky characters who lose all sense of reality,” he says. “Is this a Southern thing? No. I think it’s in a lot of places. I can think of one who came out of New York recently.”

Denton, the newspaper reporter, recalls being surprised by the bitterness, and ultimate tragedy, of the campaign between Looper and Burks.

“It would not be so shocking today, but at that time, we hadn’t had Trump or any of these other type of politicians that glory in running their opponents down,” says Denton. “There’s never been anything like that here, so it was shocking.”

Tommy Burks, Nov. 23, 1983