This story is a partnership between the Nashville Banner and the Nashville Scene. The Nashville Banner is a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization focused on civic news. Visit nashvillebanner.com for more information, and to sign up for the Banner’s newsletter.

What occurred a century ago this month in the courtroom of the Rhea County Courthouse refuses to be forgotten. The utterance of a name — Scopes — is a reminder of those two torrid weeks in July 1925 when the world’s eyes were on Dayton, Tenn., a small town about 150 miles east of Nashville.

Through the decades, The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes assumed the mantle of “the most famous trial in America.” Academics explored the subject in thousands of theses and dissertations. Hundreds of nonfiction writers and documentarians plumbed trial transcripts and personal records of the trial’s major (and minor) participants to craft explanatory narratives. Broadway and Hollywood paid tribute with Inherit the Wind, which was based on the events of that July.

Why should 21st-century Americans pause to ponder a judicial proceeding where the principals have moldered in their graves since long before the end of the last millennium?

Consider these questions: What should children be taught in school? Can science be trusted? Does government have the right to dictate cultural values? What does the Constitution mean by freedom of religion? By freedom of speech? Who defines the future in a democratic society?

If you think these are battle lines drawn by 2025 society, you would be correct, but the colliding fault lines that are fracturing today’s electorate were rumbling in 1925, and the shaking hasn’t abated.

A century ago, the country was still reeling from an influenza pandemic and World War I, even as the populace was becoming accustomed to the wonder and ubiquity of mass communication via radio. In the current age, the U.S. is fresh from two decades of conflict in Afghanistan and Iraq and a novel coronavirus that killed hundreds of thousands. Meanwhile, Americans are bombarded moment to moment with algorithmically driven information (and misinformation) that feeds high levels of anxiety.

Both eras represent times of immense change. Historian Brenda Wineapple, who wrote the 2024 book Keeping the Faith: God, Democracy, and the Trial That Riveted a Nation, describes the frazzled ethos of 1925 America this way: “The old order was indeed changing, and to many Americans change was defined as capricious, unpredictable, and if not stopped, wholly sinister.” In the face of changes that futurists predict — with AI and its attendant disruption standing front and center — it’s easy to apply that same line to 2025.

What happened in Dayton so long ago wasn’t just “monkey business.” It could be interpreted as a premonition for this modern age. As William Faulkner wrote: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Dayton is an average small town, half southern, half northern and fairly evenly divided politically. H. L. Mencken (of the Baltimore Sun) doesn’t like it because it has 62 Scottish Rite Masons. Its people are prosperous and well dressed, although some of the younger set do play slide trombones.

—Reporter’s Notebook (author unnamed), The Tennessean, July 11, 1925

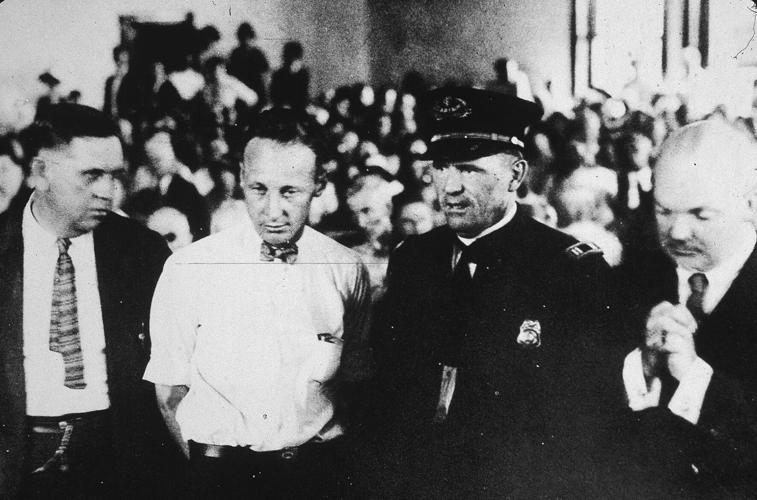

John Thomas Scopes (second from left) in the Rhea County Courthouse, July 1925

Ostensibly, the trial was convened to determine whether Scopes, a 24-year-old teacher at Dayton High School, taught evolution in defiance of the Butler Act, which was signed into state law earlier in the year. The case quickly evolved (no pun intended) into a media-fueled frenzy, featuring the first trial broadcast live on radio. The press corps swelled to more than 150 newspaper reporters and photographers. A simple question about one teacher’s actions turned into a battle royale, where figurative dividing lines were drawn in the mountain loam; where celebrity lawyers — Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan — pitted modernity against old-time religion.

And the attentive world was pointedly asked to choose a side — if they could.

Throw in a sideshow of street-corner preachers bellowing fire and brimstone, end-of-the-world prophets holding signs declaring impending doom, opportunistic vendors hawking lemonade, hot dogs, ice cream, anti-evolution books and trial souvenirs, thousands of curious spectators milling about, and a suit-wearing chimpanzee named Jo Mendi strolling the tree-lined sidewalks and you have an overview of the Scopes trial of 1925.

But let’s not get ahead of the story.

A visit to ground zero of the 1925 anti-evolution bill requires a trip off the beaten path to Macon County. There, on a 75-acre farm 3 miles from the county seat of Lafayette, John Washington Butler lived in a white clapboard home his grandfather built in the late 1800s.

Butler, who was 49 in the summer of the Scopes trial, was a farmer and respected citizen. He and his wife Nola, short for Magnolia, raised two daughters and three sons. For several years in young adulthood, Butler served as a schoolteacher. In those days, classes were held for just three or four months during the winter so that crops could be tended. Although he left teaching, concern for youth — and their future — remained a driving force in Butler’s life.

In the summer of 1922, friends urged him to run for state representative, and Butler was elected that fall to represent his home county as well as Trousdale and Sumner counties. In 1927, he moved to the state Senate. Although he served for less than a decade, he made his mark on history.

Butler was a tall man, in the range of 6 feet, with broad shoulders, large hands and a firm jaw that always seemed to be locked in position. In the many photographs taken of him in 1925, he never cracked a smile.

That’s not to say he wasn’t friendly. Several weeks before the court proceedings, a Nashville Banner reporter spent the day with Butler on his farm. “He is not the hard-faced, unrelenting zealot of popular conception,” the reporter observed in a thousand-word piece that took up most of an inside page. “To the contrary, he is a good-natured, companionable, jovial fellow.”

Regarding evolution, however, Butler found nothing to smile about. “I look upon that theory as infidelity and opposed to the Bible,” he explained to the reporter. Butler made clear he could not accept that “man is descended from the lower order of animals.”

The state representative’s journey of faith did not stray from the precepts he was taught as a child at nearby Testament Primitive Baptist Church. “I believe in the Bible just as it was printed and that it was written with the divine inspiration of God,” he told the reporter, adding that although he didn’t “claim to understand all of it,” Butler accepted the holy book as “true, every word of it.”

Including the timetable of creation in Genesis.

Butler acknowledged to The New York Times in a 1925 interview that he “didn’t know anything about evolution” when he submitted his anti-evolution bill for consideration. The impetus for the legislation came from newspaper reports — Butler was an avid reader of newspapers — that told of students returning from college changed by their acquaintance with Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species.

“Boys and girls were returning home from school and telling their mothers and fathers that the Bible was all nonsense,” he told the Times. “I didn’t think that was right.” Butler contemplated the matter for several months before deciding the state of Tennessee should intervene.

On a cold January day before the legislature convened for its 1925 session, Butler reached for a pencil and paper and settled into a chair in front of a blazing fire at his home. He was determined to write an anti-evolution bill that would prohibit the teaching of evolutionary thought in all public schools, including universities. Just as important to him was a second provision: to prohibit the teaching of any theory “that denies the story of the divine creation of man as taught in the Bible.”

“I wrote the bill myself, making six or seven trials at it before it suited me,” he told the Banner reporter. Butler said the bill’s language was of his own creation, with no outside help. “I have heard it said that somebody was ‘back of me’ in the introduction of the bill, but that is not correct.”

On Tuesday, Jan. 27, the Butler Act received overwhelming acceptance in the lower chamber of the General Assembly, less than a week after the measure was introduced.

The Senate, on the other hand, took its time. After being rejected by the Senate Judiciary Committee, the bill appeared beyond resuscitation, but an external force, namely the charismatic evangelist Billy Sunday, revived it. In a series of revival meetings throughout February in Memphis, the fundamentalist attracted tens of thousands who were exhorted to resist the ways of the world and to turn to God. On several occasions, Sunday fixed evolution in his sights, bellowing to the faithful that “education today is chained to the devil’s throne.” He praised the Tennessee House of Representatives for taking “action against that godforsaken gang of evolutionary cutthroats.” The crowd roared with applause and shouts of “amen.”

The Tennessee Senate minded their cues received from Bluff City. The “evolution bill” was returned to committee, where it was promptly referred to the full body for a vote on March 13, a Friday. A chorus of hecklers, mostly Vanderbilt students, filled the galleries to shout their opposition, but the measure was handily approved.

Gov. Austin Peay signed the Butler Act without reservation. He expressed confidence that “the law will never be applied.” State Rep. Butler believed the same. He assumed “everybody would abide by it [and] we wouldn’t hear any more about evolution in Tennessee.”

John Thomas Scopes, the amiable science teacher and football coach at Dayton High, was charged with teaching evolution about six weeks later.

The game was on.

“My dad told me, ‘Did you know that your great-grandfather wrote the monkey law?’ Growing up, I knew nothing about none of this. I went away and joined the military after high school and was gone for almost 20 years.

“I would have liked to have met him. I would have just sat and listened to everything he had to say. I believe he was doing good. I’m Baptist. I try to raise my kids that way. There’s only one way that man came to be and that is that God created us.

“He was trying to write a law that would do good for the public schools in Tennessee. God bless him. When I learned about all this, I thought to myself, ‘Well, I guess I do have an interesting family.”

—Cynthia Harris of Castalian Springs, great-granddaughter of John W. Butler, author of the 1925 anti-evolution bill.

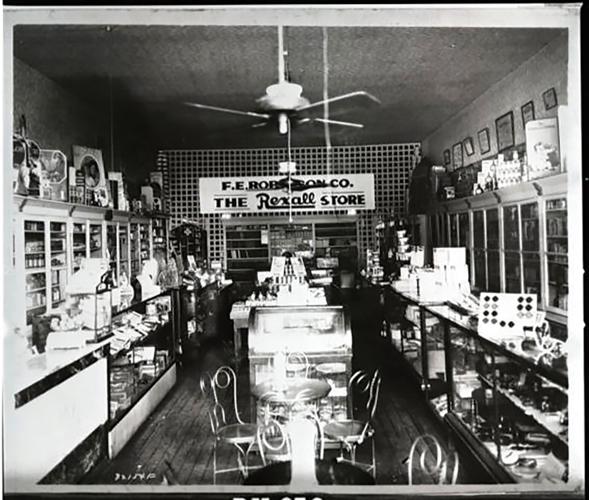

Robinson’s Drug Store in 1925

It should be stated that Scopes might have never mentioned “evolution” to Dayton High students, much less taught the controversial science behind the word. Yet as incongruent as it sounds, he agreed to say he did, was charged and, soon enough, his name and photo appeared in newspapers from Poughkeepsie to Sacramento.

That happened because of the confluence of specific actors and factors.

After the Butler Act was signed by Gov. Peay in March 1925, the fledgling American Civil Liberties Union decided to test the law’s constitutionality. The organization circulated an appeal in newspapers for a biology teacher who had taught evolution. On Monday, May 4, the Chattanooga Times published the ACLU’s notice. A representative of the New York-based organization stated that the “law strikes so serious a blow at scientific teaching that we cannot let the issue rest until it has been passed upon by the highest courts.”

It was the Chattanooga paper, which circulated in Dayton, that caught the attention of George Washington Rappleyea, a civil engineer with expertise in metallurgy. He had moved to Dayton, his wife’s hometown, to manage the faltering Cumberland Coal and Iron Co. At one time, the company had been the economic engine of the county, but by 1925, the enterprise was hampered by outdated equipment and reduced output from its mine. Effects of the company’s downturn rippled through the community.

Rappleyea (rhymes with “apple-yay”) was an improbable instigator of the Scopes affair. He was a transplanted New York City native. He didn’t sound like other Daytonians, nor did he look like them — short, swarthy, with a head of bushy dark hair. Despite these differences, the town accepted him. He was active in the Methodist church, a member of community clubs and friendly with the town’s movers and shakers.

On May 5 Rappleyea entered Robinson’s Drug Store with the Chattanooga Times in hand. There, Frank Earl Robinson, owner of the store, and other members of the town’s Progressive Club frequently gathered to confab. Rappleyea broached his big idea of using a legal proceeding on evolution to draw thousands of visitors to Dayton. The attention, he predicted, might linger beyond the hoopla of the trial. Those present liked the sound of it.

For the role of the evolution-teaching instructor, Rappleyea suggested Scopes. According to one account, a high school student was at the store’s soda fountain, and Walter White, the school superintendent, sent the young man to fetch Scopes.

When Scopes answered his summons to the drug store, he faced a contingent of the town’s leading businessmen and his boss. The group was engrossed in a dispute about evolution. Rappleyea directed the attention to Scopes, asking if biology could be taught without mentioning evolution. No, the teacher answered.

To prove his point, he moved to a shelf where state-approved textbooks were displayed (students had to buy their own in 1925) and pulled a volume titled Civic Biology by George Hunter. He noted the book’s “Evolution” section.

That’s when Rappleyea sprang the trap. He explained the ACLU’s offer to fund a test case and asked Scopes if he would be the bait. The blue-eyed young man, a year out of the University of Kentucky and in his first year of employment at Dayton High, was not eager to accept. Nor did he think his teaching experience was applicable. Scopes didn’t normally teach biology, but he had been called to substitute earlier in the semester when the regular teacher was absent due to illness.

And as stated earlier, Scopes wasn’t sure evolution came up in class.

No one present, save the teacher, saw that as a problem.

Everyone warmed to Rappelyea’s plan. Before the group dismissed, Scopes, who supported the teaching of evolution, also agreed to participate. He would later regret being thrust into the spotlight, but on that spring day in 1925, everyone gathered around the cafe tables at the drugstore was of one accord: The evolution debate would be brought to Dayton.

As the trial date neared, Robinson hung a banner outside his drugstore. It read: “Where it all started.”

He couldn’t imagine that a century later his sign would still be remembered, if only as an epitaph for a season of strangeness.

Twice, the sweating, mopping, fanning throng burst into applause. When Bryan entered the room, they cheered. They shouted even more wildly when a candidate for the jury testified that “of course” he believed the Bible.

—The Associated Press, July 11, 1925

Michael Lienesch, a retired UNC-Chapel Hill professor, is not surprised to find the issues that divide America in 2025 mirror concerns from the era of the Scopes trial.

“It’s not like a river or cycles, but for the last 100 years, the same questions keep being debated and discussed,” says Lienesch. “What does progress look like? What is modernity? We saw it then. We see it now.”

Further, these questions are often rooted in the most personal of contexts: belief in a supreme being, expression of faith and definition of a moral life. These queries also have led to disputes, where basic freedoms granted by the U.S. Constitution are forcibly reconciled to the credal thoughts of others.

In 2007, Lienesch examined the rise of American anti-evolutionism in a book, In the Beginning: Fundamentalism, the Scopes Trial, and the Making of the Antievolution Movement. With a focus on American political theory, Lienesch’s book explores how fundamentalism, of which biblical inerrancy is a key tenet, has grown systematically over the past century.

“It’s not something that was invented by Jerry Falwell,” he says. “Fundamentalism began at the end of WWI. Preachers created movements.” Political activism centering on religious conservatism has been the result, particularly in the past 50 years.

“Today, the role of political parties is so closely tied to religious conservative activists,” Lienesch says. “In the day of Scopes it was different.” During the Scopes trial, “Society had their own version of culture wars.”

“In 1925, the secularization of society was much discussed,” he says. “Students were going off to college to learn new ideas, and people were drinking alcohol during Prohibition.” The divorce rate also began rising, and the attractions of life in America’s metropolises led many to seek careers off farms.

Education, particularly higher education, was also a much-discussed topic. “Academia was an issue. This was a strategy that was good politics for the conservatives in the fundamentalist movement. It all began with how to read the Bible and understand it, and that led to the question of whether the Bible was being taught in schools.”

William Jennings Bryan was an early critic of colleges and universities when it came to what was being taught. Lienesch says, “He was debating college presidents all over the country. Years before he was in Dayton, Tenn., he was traveling. I think Bryan lived a lot of his life on trains.” Bryan and others called for investigations of college curricula. He focused on evolution, especially human evolution, as a subject that could engage and enrage the masses, the retired professor noted.

Numerous college presidents buckled under pressure to make changes. A few professors lost their jobs.

Today evolution has been replaced by other topics that are worrisome to conservatives: gender studies; diversity, equity and inclusion programs; and how history is taught, among others.

“And we see some college presidents are buckling today — think about Columbia [University], for example — while others are resisting,” Lienesch says.

In elementary and secondary education, modern reform extends to displaying the Ten Commandments in every classroom. Louisiana approved such a measure in 2024, and Texas did the same a few weeks ago. Legal challenges are already underway in both states.

“You know, the Scopes trial was seen as a great defeat for fundamentalists,” Lienesch says. “When Darrow put Bryan on the stand, that was not just quite a show. It was also very revealing to a lot of people. It revealed inconsistencies, some of the limitations of fundamentalist thinking at that time.”

But they weren’t down for the count.

“The fundamentalist movement and the conservative Christian movement retreated a bit, and they began to build institutionally, and this is not surprising that they are very much with us.”

I think my feelings go along with my grandfather’s. I’m very much a Christian, and so I read the Bible daily. I don’t really think there is a separation in church and state. I think that’s all politics. I’m so sorry that they don’t allow the teaching of religion in schools.

When I was in medical sales I would come to Dayton. And while I was there, I would try to talk to people about it, but the people I was talking to were too young to remember it. As many times as I’ve been to Dayton, I’ve never been to the courthouse. I didn’t know it still existed. I think it’s interesting that it does.”

—Bill Link, 83, a native of Waverly and grandson of Judge John T. Raulston

News of a Tennessee teacher being charged with teaching evolution flowed through the country with the rapidity of a wildfire blown by constant winds.

The story caused a stir in Memphis because the World’s Christian Fundamentals Association, an organization created in 1919 to defend traditional biblical values from the influence of modernism, was having its annual convention there. The group’s keynote speaker was William Jennings Bryan, three-time candidate for president, ardent fundamentalist and someone who had been denouncing evolution for years at outdoor Sunday school sessions he held in Florida, where he lived.

A day after Bryan’s appearance at the convention, the organization named him to “represent their interests” at the Scopes trial, notwithstanding the fact that WCFA had no legal standing in the Rhea County matter. Having already moved on to his next speaking engagements in Ohio and Pennsylvania, Bryan took a day or so to consider the offer before replying with a telegram from Pittsburgh. “I will do it,” the Great Commoner told reporters. “We cannot afford to have a system of education that destroys the religious faith of 75 percent of our children.”

The matter of whether Bryan, who had not litigated a case in 30 years, could officially join the prosecutor’s team was resolved by an open-arms invitation on May 13 from Sue K. Hicks and Wallace C. Haggard, Dayton attorneys who were the lead prosecutors. Such was his popularity, Bryan’s entry into the fray brought exponential interest in the case nationwide.

Two days later came another shock: The defense announced that Chicago-based attorney Clarence Darrow had joined the fight. The inclusion of the sharp-tongued Darrow, who was considered by many to be the best defense lawyer in the nation, made clear the dividing line between the two camps.

Darrow offered an irreligious counterpoint to Bryan’s unabashed devotion to Christendom. Headlines pitting the two against one another, as if they were heavyweights vying for a championship, appeared with regularity in newspapers large and small.

“Civilization and not a school teacher are going on trial,” Darrow told the Associated Press.

Even before word arrived that Bryan and Darrow were coming to Dayton, townspeople began sprucing up. The interior of the courthouse received new coats of paint. Lights and benches were installed on the grassy area bordering the square. To quench the thirst of visitors, drinking fountains were installed. To house the phalanx of reporters who didn’t secure lodging at the hotel or in boarding rooms, cots were assembled in large upstairs storage rooms at two downtown businesses, Bailey’s Hardware and Morgan Furniture.

The tall windows inside the courtroom were cleaned of dust and grime. Technicians from WGN radio in Chicago unspooled hundreds of feet of cable to connect their mobile studio in the courtroom to the local telephone exchange and to install speakers on the courthouse lawn.

“Gosh! I didn’t know we would stir up all this that day the evolution bill went through the House [of Representatives].”

—State Rep. D.Y. Conatser of South Pittsburg, The Tennessean, July 11, 1925

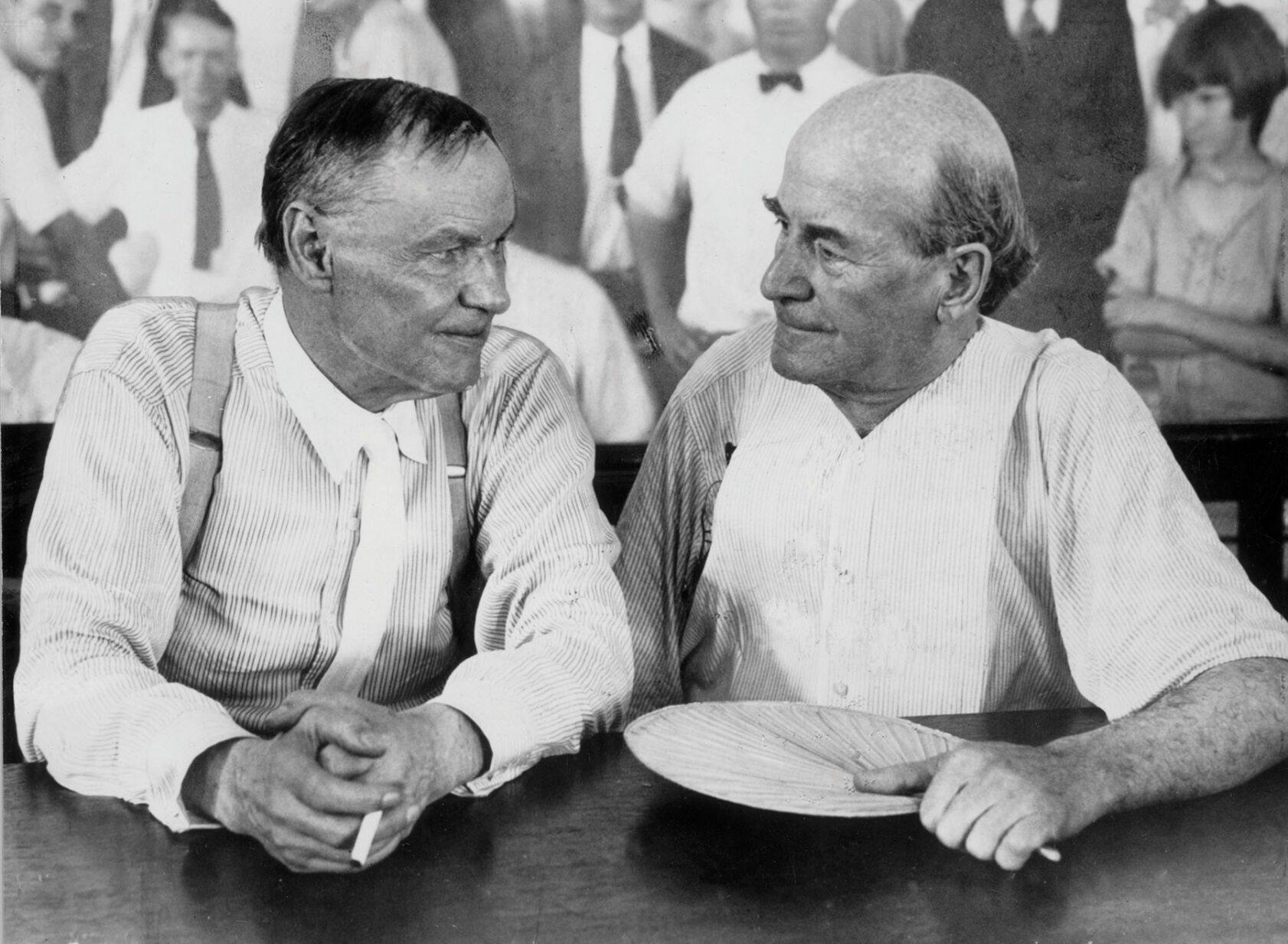

Clarence Darrow (Left) and William Jennings Bryan, July 1925

The trial began on July 10, a Friday, and ended on July 21, a Tuesday. Judge John T. Raulston, who was midway through his first term as judge in Tennessee’s sprawling 18th District, would preside. He was born in rural Marion County in 1868, just three years after the Confederacy surrendered at the Appomattox Court House. After college, he studied law under the tutelage of an attorney in Chattanooga and passed the bar exam in 1896 at age 28. He established a practice in Winchester, Tenn., the Franklin County seat, before being sworn in as judge in 1924.

Raulston, 56, was excited the trial was coming into his jurisdiction. If he had doubts or concerns about the unusual case about to unfold in his courtroom, he kept them to himself.

Genesis describes the world being created in six days, with God resting on the seventh. The “Monkey Trial” of 1925 took eight days, with two weekends interrupting court, offering a respite from the legal jockeying and the oppressive temps and giving preachers two Sundays to focus their homilies on the evils of evolution. Outside, the thermometer hovered in the 90s. Inside the standing-room-only courtroom, the heat felt like 100 and above. Overheated spectators in the gallery fainted with regularity.

The eight days in court unfolded like most trials, in an undramatic fashion. The first day was spent selecting a jury — 12 men, mostly churchgoers and farmers. Days two and three mostly involved the nine lawyers jawing back and forth on legal issues: whether the defense leaked information to the press (they did not), whether to quash Scopes’ indictment (it was not), whether it was appropriate for prayer to open each day’s gathering (yes, said the judge).

It wasn’t until the fourth day — Wednesday, July 16 — that Scopes pleaded not guilty and the state presented its case. The first witnesses called were the school superintendent and two students who attended the biology class where evolution was allegedly taught.

On the fifth day, the prosecution entered a motion to exclude testimony from expert witnesses (geologists, biologists and chemists, among others) that the defense had arranged to be in Dayton for the trial. No decision was reached by the time of adjournment for the day.

On Friday, day six, Raulston ignited a firestorm as he ruled the scientists ineligible to testify. Convincing the judge to change his mind was a futile enterprise for Darrow and company, but they tried nevertheless. They sought to enter affidavits of the scientists into the record, but the prosecution objected all along the way, and Judge Raulston mostly agreed with their objections, which peeved Darrow. He muttered a string of sarcastic rejoinders, interrupting the jurist several times. The defense attorney questioned why “anything that is perfectly competent on our part should be immediately overruled.”

“I hope you do not mean to reflect upon the court,” Raulston replied, his words no doubt freighted with rising anger.

“Well, your honor has the right to hope,” Darrow shot back.

First thing on Monday morning, day seven, the judge charged the Chicago lawyer with contempt of court and set a bond of $5,000. Darrow was unsure whether he could quickly secure funds, but a Chattanooga lawyer, Frank Spurlock, piped up that he would cover the bond. This revelation prompted chattering among the hundreds of spectators. Kelso Rice, a young Chattanooga police officer on loan to Dayton, bellowed a demand for quiet.

“This is not a circus,” he exclaimed.

Maybe not a circus, but nothing resembling normal, either.

Following lunch, Darrow offered an apology that was accepted by Raulston. They solemnized the moment by halting court business long enough to be photographed shaking hands.

Afterward, the judge told the overflow crowd that the trial was moving to the courthouse lawn for the rest of the day.

“I am afraid of the building,” explained Raulston, who had been made aware that pieces of plaster were falling onto the floor beneath the courtroom. The cause seemed to be stress from the weight of hundreds of standing spectators who refused to leave.

Consequently, the most important lawyer-witness exchange in the Scopes trial came to be held in the midday light, beneath a blue summer sky.

The matchup was improbable: “The defense desires to call Mr. Bryan as a witness.”

All the headlines promoting a clash of titans were coming true.

Even if you had proof to show me that evolution was true, you couldn’t drive it into my head with a mallet. … A man can’t believe in the Bible and believe in evolution at the same time.

—Carl Francisco, 27, resident of Lone Mountain, Nashville Banner, July 12, 1925

The challenge with teaching evolution in 2025 is the same each semester, says Elizabeth Barnes, who is now approaching her fifth year on the biology faculty at Middle Tennessee State University.

“I would say one of the biggest things that we face when we go to teach evolution is this perception that in order to accept evolution, to actually believe that evolution is a real thing, that you have to be an atheist or reject religious belief,” Barnes says.

A national survey of biology students conducted by Barnes and other researchers in 2022 showed that 50 percent of the respondents believed acceptance of evolution was a rejection of God.

“That’s just a misunderstanding of the nature of science,” Barnes says.

Although the Butler Act was repealed in 1967 and there’s no current move today to ban the teaching of evolution in Tennessee’s public schools, introducing students to the subject remains challenging. But it’s a challenge the 38-year-old assistant professor has accepted, determined to convince her students that the topic doesn’t have to negate science or God.

Thomas Huxley, a contemporary and friend of Charles Darwin, coined the term “agnostic” in 1869 as he was trying to find a way to settle debates about the religious or antireligious nature of science, Barnes notes.

“Huxley said that science is a process that doesn’t have the means to determine whether or not something outside of the natural world is influencing the natural world.”

In other words, science says that evolution happened. How it happened, well, the debate continues and likely will: everything from the creation narrative found in Genesis to the cosmological slow dance of creation that followed the Big Bang.

“But these ideas of deistic, theistic, agnostic and atheistic evolution are equally compatible with what we know from science, because it’s not really science’s job to tell you whether God exists or whether God had an influence on the natural world,” Barnes says.

Science’s job, she adds, “is to determine what did happen in the natural world.”

Although students in Tennessee’s public schools are exposed to evolution in high school biology classes, per the state’s science standards, Barnes has found that many of her students don’t have a firm understanding of evolution when they arrive at her classroom. That may be because students took biology early in high school and did not retain the material. But many, she says, have concerns about reconciling their faith with science.

Barnes was introduced to evolution in a biology class at a community college. She calls it “one of the most beautiful, amazing ideas that I ever heard of.” At the same time, Barnes says she also “learned that about 60 percent of the United States doesn’t think that evolution was real.”

A year or so later, when she was taking upper-level biology classes at Arizona State University, she was confounded by research professors who “were talking about evolution in a way that kind of put evolution and religion against one another.” Although Barnes is not a person of faith, she recognized that fellow students who were churchgoers were wrestling with this teaching approach, sometimes to the point of dropping the class.

“It seemed to be very conflict-inflating,” Barnes says.

She wondered if there wasn’t a better way. That prompt led to a major focus of her research: teaching evolution in a manner that reduces conflict.

In the Bible Belt, many students bring religious values fashioned by teachings that are opposed to evolution, Barnes says. Through her research and teaching, Barnes says she’s learned it is possible to nurture scientific inquiry without being dogmatic to the point of negating someone else’s faith.

“What we really want them to be able to do is evaluate scientific evidence, you know, apart from their personal biases,” she says. “What I’ve said [to students] is that I don’t come in here and teach you science just so you can learn the facts and not be able to do anything with them.”

Her job, she says, is not to make students accept evolution. Every semester, Barnes tells her classes: “It’s not my job as an instructor to grade you on what your beliefs are. Or to judge you on what your beliefs are. My job is for you to understand the science.”

She’s confident her approach has made a difference.

“I get emails from students, or they come up to me after class, you know, talking about how they have been so relieved to not have to pick between their science and their faith.”

Infectious laughter ensued when someone passed a caricature of Bryan … as a member of the jungle race. The picture, captioned, “Yet he denies his lineage,” was passed to the Floridian who shook with appreciative convulsions. The judge came down to look at the exhibit. He chided the fundamentalist champion: “It’s a work of art.”

—Reporter’s Notebook (unnamed author), The Tennessean, July 11, 1925

Why William Jennings Bryan agreed to testify isn’t clear. Perhaps he was overconfident, even cocky. Perhaps he felt a providential calling to set the infidel Darrow straight. Perhaps the opportunity for Bryan to call Darrow as a witness was the impetus.

Regardless, the afternoon came to grief for the Great Commoner in the temporary open-air courtroom. For more than two hours, Bryan, fanning himself with the pages of a King James Bible, was peppered with questions that tested his allegiance to biblical infallibility.

Was Jonah swallowed by a whale? Did Joshua make the sun stand still? How old is the earth?

When many people think of this scene, they recall a clip from Inherit the Wind, the stage play based on the Scopes trial that was made into a movie in 1960 starring Spencer Tracy and Fredric March as the characters patterned after Darrow and Bryan, respectively. The movie version is a clear takedown of Bryan, a man of conviction who blinks first, a man for whom a seed of doubt was planted. The scene ends with close-ups: of Bryan struggling to find words to repair the damage; of Darrow, smug and quiet.

Many Daytonians do not like the movie, particularly the depiction of locals as slow-talking, ignorant and uncertain of the world beyond the mountains.

A close reading of the trial transcript reveals Bryan delivered many stinging rebukes of Darrow, but it was the answer to one question that turned the tide: Do you think the earth was made in six days?

“Not six days of 24 hours,” was Bryan’s reply.

For many in the press, these six words were interpreted as a seismic rendering. Bryan appeared to have disturbed a fault line, leading to a view that the world was much older than the faithful believed, older than Bryan had testified less than an hour earlier. Even though Bryan had expressed this distinction when he was on the speaking circuit, most of the secular press in attendance took no notice and judged Darrow the winner. Many of their readers did too.

The seventh day of the trial ended with the protagonists shouting at each other in tandem.

Bryan: “I want the world to know that this man, who does not believe in a God, is trying to use a court in Tennessee …”

Darrow: “I object to that …”

Bryan: “… to slur at it and … I am willing to take it.”

But Darrow was through with his witness.

“I am exempting you on your fool ideas that no intelligent Christian on earth believes,” he said, returning to his seat.

After which Judge Raulston adjourned court until the following morning.

On the last day of court, Tuesday, July 21, blessed rain fell from the skies and mist hid the verdant hills surrounding Dayton. The trial resumed in the courtroom, where welcomed breezes streamed through the tall windows.

Bryan did not get to question Darrow or make a closing speech, which he had been preparing for days. The reason? The defense asked that their client, John T. Scopes, be found guilty so the matter could be appealed. Raulston accepted the request, charged the jury and sent them out to deliberate, which they did for a total of nine minutes, returning at 11:23 a.m.

Scopes was fined $100 by the judge, not the jury, and it was based on this technicality that the Supreme Court of Tennessee later overturned the fine even as it ruled the Butler Act was constitutional. Instead of remanding the case to Rhea County, the justices noted “that nothing is to be gained by prolonging the life of this case.” Instead, they urged the prosecutor to withdraw the matter from further prosecution — and that’s what happened.

The teacher and football coach never had to pay the fine. He left Dayton, went to college in Chicago and became a geologist for the gas and oil industry, living in South America for a time, before settling in Louisiana.

In April 1970, Scopes accepted an invitation to address students at Peabody College in Nashville. The occasion was the upcoming 45th anniversary of the trial. Three years after his autobiography had been published, Scopes was content to reminisce and offer commentary, especially to aspiring teachers.

On that spring day, he spoke his mind.

“The only place a teacher should ever be interfered with is when the child begins to think for himself,” he said. “Then that child should be consulted about his own education.”

Scopes advised the packed auditorium to hold strong against “outside pressure groups and government controls [that] have dictated to the schools to the point where they do not exercise the one thing man has above other animals — the right to think.” According to newspaper reports, students rose to their feet and cheered, the ovation continuing for several minutes. A photo shows Scopes, leaning on a lectern, hand on his hip. No longer was he the wide-eyed Dayton High teacher, his head topped by a straw hat, his eyes framed by round spectacles, his face the image of youth. Here was a slightly stooped man of 69, assessing lessons he’s learned.

On the question of whether he taught evolution at Dayton High, Scopes told the audience he was at the mercy of a faulty mind — his.

“I substituted for 10 days for the biology teacher … and during that time, I didn’t want to start on any new chapter, so I just reviewed what the class had been over. It may have included evolution. I just don’t remember. But I don’t see how I could have reviewed for 10 days and not touched on evolution.”

That was likely his final word on the subject, because the Peabody College visit was his last public appearance. On July 1, Scopes was hospitalized for gallbladder surgery, but the diagnosis was soon changed to terminal cancer. He died Oct. 21, 1970.

The next day, his photo once again appeared in newspapers from coast to coast.

On the way to Dayton one morning we came upon an old man walking with a cane and stopped to pick him up. One of us asked, “Going to Dayton to the big trial?”

“No sir,” he responded. “I’m going to get a chaw of tobacco.”

“Well, what do you think of the trial?” we asked.

He responded, “They [referring to the influx of northerners into Dayton] ain’t down here for no good. There’ll be another war. You just wait and see. They’re down here to get the lay of the land. But next time, the South will beat ’em.”

—Story told by Oren Metzger of Spring City, March 1978. Published in the foreword to the 1990 reprint of the Scopes trial transcript.

This statue of Clarence Darrow, who represented John T. Scopes in his 1925 trial, was unveiled during the summer of 2017.

On a recent spring morning, Dayton was looking fine beneath a sky dotted with feathery clouds. Front yards were coming alive following winter’s hiatus. Tall forsythia bushes, bending under the weight of blossoms, created fountains of yellow. Tulip stems, having broken through the crust of dark soil, pointed to the stratosphere, a promise of delicate flowers in pastel colors soon to come. Catkins, nature’s delivery system for scattering oak tree pollen, dropped lazily to the ground, their usefulness served.

Downtown merchants flipped signs to “Open,” and a few of them propped doors ajar, the better to enjoy such a glorious morning. Traffic was light on Market Street. The din of the busy state highway less than a half-mile away could barely be heard. A morning train thundered through town without stopping, but the blaring of its horn soon faded along with the sound of steel rolling on steel as the last car disappeared. A hundred years ago, passenger trains paused several times a day here, but now only freight headed elsewhere rumbles through.

Outside the historic Rhea County Courthouse, grasscutters completed their trimming assignment of the lawn, and the seductive smell of summer floated on constant breezes.

This historic structure, built in 1891 and featuring a classic blend of architectural styles, makes imagining the events of July 1925 a bit easier. The bones of the building remain unchanged in the digital age. Daytonians, thousands of them, have come and gone, from birth to grave, since the Scopes trial, but the brick building that attracted a worldwide audience a century ago still stands, unperturbed, a solid connection between past and present.

John Fine is pleased to straddle that gap. He’s 62, retired as the county’s clerk and master and before that as circuit court clerk. Considering his tenure as an employee of the electorate, Fine has spent a significant portion of his waking hours in this historic space.

In retirement, he hasn’t strayed far. Each week, he returns as a docent at the Scopes Museum in the courthouse basement.

“They called us Monkey Town,” Fine says, sitting at a desk in the center of the museum, an oversized photo of John T. Scopes behind him. “A lot of people didn’t like it, the nickname, but they were very proud that this was the most famous courthouse in America.”

He launches into the trial without a prompt.

“I think they thought it’d just be a little breeze and get our name in the paper, but it turned into a tornado,” says Fine, referring to the gang at Robinson’s Drug Store. “They got their economic stimulus while the trial was going on, but after …”

Fine paused a beat before continuing: “… it all dried up.”

“Someone asked me one day, ‘Is that what got industry and factories in Rhea County?’ I said, ‘No, it was TVA and the railroads that did that.’”

One floor above Fine in the county historian’s office, Pat Guffey agrees with that assessment.

“Really, it didn’t do much for the town as far as the economy went,” says Guffey. “It did put it on the map, I guess you could say. Nothing lasted, except Bryan College.”

Guffey notes the college located on a hill overlooking the town. It was built in honor of William Jennings Bryan, who died in Dayton five days after the Scopes trial ended. In the past 90 years, thousands of students have matriculated through the school’s academic programs. About 1,400 students are enrolled today.

What is the trial’s lasting effect on locals as the 100th anniversary approaches? A walk down Market Street offers hints.

Chip Beaulieu, 60, is the pastor of Word of Truth Church, located a few blocks south of the courthouse. His path to the pastorate was unusual. For years after graduating from Tennessee Tech, he worked in the space shuttle program at NASA in Huntsville, Ala.

“I was in mechanical engineering, structural analysis,” he says, seated in the church’s worship center, a refurbished building that features exposed trusses built by a bridge company.

But Beaulieu (pronounced “bolio”) always sensed that he would one day serve as pastor. About 12 years ago, he and his wife Chris, drawn by prayer, arrived to start a church.

What does his flock think of the long-ago struggle in the courtroom down the street?

“We’ve talked about it,” Beaulieu says. “It was all based around evolution, putting the monkey on the stand, which was great theater, I’m sure.”

But as an explanation for the creation of man, the pastor says he’s not picking up what evolutionists are putting down. Ironically, his degree in engineering, and the science he studied to receive it, point the way for him.

“I just think it’s the most fantastic type of theory, because the level of faith that’s required to believe in it exceeds the Christian word. The basic premise is that every single feature of a human body was created by an accident, of some fault, and DNA somehow made it to the next generation.”

The chance of such an effect happening is “not almost zero,” he says. “It’s zero.”

“To me, it’s a lot easier to believe an almighty God created [life] in seven days than innumerable accidents over billions of years.”

He’s not surprised, however, that much of America has adopted a less literal view of Genesis. “Mankind always is trying to outsmart the Lord, and with AI, you know, they’re almost as smart as God.”

Or so they believe, he adds.

“Somebody even told me that because Google exists that we know everything there is to know, and so I will just ask them to tell me how gravity works,” says Beaulieu. “Nobody knows. I can measure it and quantify it and calculate it. But where does it come from? They still don’t know.”

Evolution, Beaulieu confirms, isn’t on the minds of his church members, many of whom returned to a life of faith after distancing themselves from the mainstream churches of their youth. Today, he says, the perceived concerns focus on other issues: what students are taught in school, the proliferation of transgender rights, the general decline of American morals.

“That’s the fight for today,” he says.

At a nearby dog park, Gloria Rapson sits on a bench watching Luna, her labrador/shepherd mix, run in wide circles. A resident of Dayton for several decades, Rapson was aware of the Scopes connection to Dayton, but says she was unaware that the 100th anniversary was approaching.

“You know it happened here, you just don’t think about it all the time,” says the retiree, a school lunchroom worker and manager for 28 years.

But these days, she often ponders America and its direction.

“You know, way back we wanted to separate religion from the state. We wanted to make sure that everybody had that freedom to worship.” Even so, the 69-year-old recalls that when she attended elementary school,“We started with prayer and we still had the pledge.”

Today, she offers, “Nobody wants [prayer] in the schools now, but our schools need prayer.”

Dayton, Rapson observes, is no different on religious issues than other Tennessee towns, large and small. A sizable number — “probably 70 percent,” Rapson guesses — are like her and regularly attend a church. But individual beliefs vary on “touchy subjects” like LGBTQ rights. “I mean, you’ve got people who are going to be for that society, and then you got people who are totally against it.”

That said, a person who needs a lending hand brings out the best in her friends and neighbors. “If you have a real serious need … the people gather and take care of it,” she says. “That’s just the way we are.”

Town historian Guffey says even though she grew up in Dayton, she was always allowed “to form my own opinions” and, most importantly, to read. “I’ve always done a lot of reading,” she notes.

Guffey, who is a former biology teacher, landed on her sweet spot of truth. “I’m a Christian so I do take the Bible view, but you can still believe in evolution and still be a Christian. And a lot of people say, ‘No, you can’t,’ but all evolution really is, is change over time. That’s all evolution is. It’s change over time.”

With a slight smile, Guffey delivers a bit of family trivia: She’s descended from the Darwins of Dayton, whose lineage can be traced — very distantly, to be sure — to Charles Darwin of the HMS Beagle.

Kismet or coincidence? She shrugs.

Back in the Scopes Museum, one floor below the county historian’s office, John Fine recalls a recent conversation he had with a college student visiting the museum. She wanted to know why Dayton received so much bad publicity during and after the trial.

Fine says he reminded the woman of historian Shelby Foote’s admonition about the importance of understanding the Civil War’s place in American history. “She asked what that had to do with Scopes.”

The former county official offers a knowing smile. “I said, ‘Well [many of] these news outlets were from up North.’ And I believe, and this is my opinion, they were bashing not just Dayton, Tenn., but the whole South. They said we were anti-science and hillbillies and ignorant. The war hadn’t been over but, like, 60 years. It was still raw.”

“It’s still raw today,” he says. “I said people are still arguing about it. She said she had never thought of it like that.”

There’s much to learn from studying Scopes, he says. And indeed, there is.

Americans are divided by a thousand flash points: climate change, immigration, health care, taxes, gun laws, abortion, book banning, racism, and the list goes on, ad infinitum.

In 2025, society’s debate on these matters isn’t like 1925, taking place in a staid courtroom before a captive audience and moderated by august and learned men asking honest questions. Instead it’s happening in all spaces — personal, public, sacred, secret — unfolding alert by alert on ever-present digital devices and without moderation, except by inscrutable algorithms, which may or may not have humanity’s best interest in mind.

Bryan and Darrow, by definition of being members of the human race, were flawed. The many examinations of their lives and letters reveal instances where they succumbed to ego and narcissism. Perhaps it is better to learn from the purest of their aspirations for the America they both loved.

Bryan is remembered for this quote: “Destiny is not a matter of chance, it is a matter of choice; it is not a thing to be waited for, it is a thing to be achieved.”

Darrow, often clever with his aphorisms, said this: “The pursuit of truth will set you free, even if you never catch up with it.”

Implied in both is a call for action. In a democracy, action requires deliberation. To arrive at a consensus requires people of different faiths, partisan beliefs, races and genders to look each other in the eye — as did Bryan and Darrow a century ago — and hear one another.

This is why that long-ago trial that was about one thing, but really was about so much more, still matters. It’s why history refuses to let it be forgotten.

As far as Fine’s take on the “e” word, “Evolution is theory,” he says.

“The whole thing is a substitute theology,” he says. “We now call it intelligent design, which I’m fine with. That just says that the supreme being did it. Science and Christianity does not conflict.”

“Preach it,” a voice calls out approvingly from behind Fine, who turns to find a smiling man and a teenage boy — visitors to the museum.

“Is the courtroom open today?” the man asks. Fine directs them to an elevator that will take the pair upstairs to the courtroom where Bryan, Darrow, Judge Raulston, Scopes and many others made history.

Unfortunately, the room’s tall walls do not speak of what they heard in 1925.

Over the years, that hasn’t stopped Fine from standing in that grand space, listening, just to be sure.

Leon Alligood is a retired MTSU journalism professor. For 30 years before joining academia, he was a reporter, most of that time at the Nashville Banner and The Tennessean. He is the co-author (with Kathy Bingham Turner) of Boss Brooks: A True Story of Fraud, Family, and Forgiveness From Tennessee to Texas, which will be published by the University of Tennessee Press in November.

This article first appeared on Nashville Banner and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Clarence Darrow questions William Jennings Bryan during the Scopes “Monkey Trial,” in Dayton, Tenn., July 1925.