On July 31, 87-year-old Karl Meyer decided to break the law.

He grabbed a blanket and drop cloth and headed to the Tennessee State Capitol, where he planned to risk a felony charge for sleeping on state property, calling his action a 24-hour peace vigil. Meyer, who has been a radical activist for 67 years, was protesting a state law that he believes unfairly targets homeless people. He had sent a letter to Gov. Bill Lee requesting an audience to discuss the constitutionality of the law.

Meyer camped near the state’s Liberty Bell replica, in a spot visible from a window in the governor’s office. It rained on him. He also chatted with an unhoused woman at one point in the night, learning about her usual struggle to find a safe place to rest.

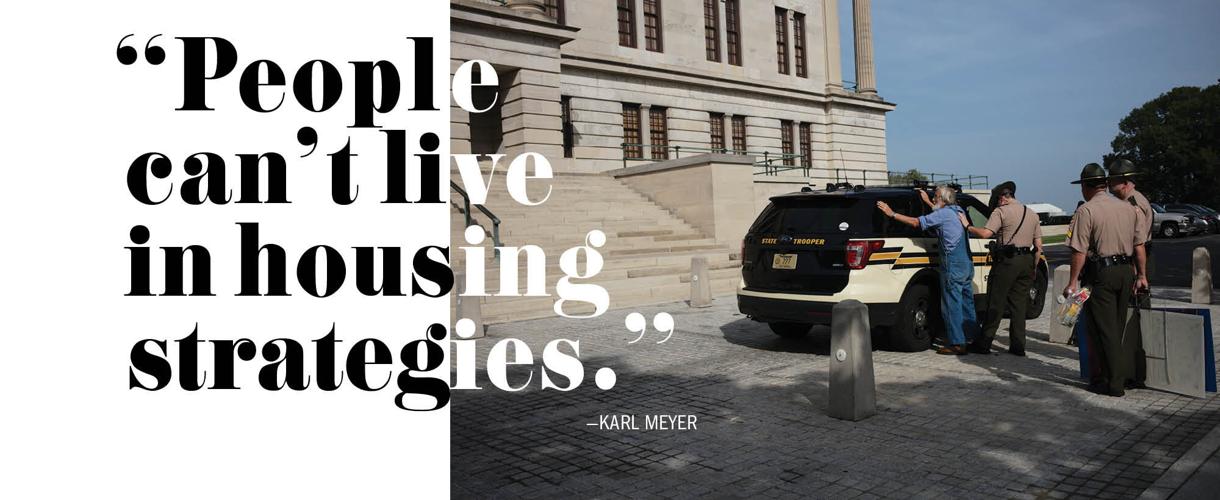

The next morning, Aug. 1, state troopers arrested him for sleeping on the Capitol lawn overnight.

It wasn’t the first time Meyer had been arrested — a 2001 profile on the activist estimated he had been arrested 50 or 60 times by that point, often demonstrating against war. Meyer later told the Scene that the arresting officer was “very professional and very cooperative.” He was charged with two misdemeanors for criminal trespassing and disorderly conduct, but not the felony violation. (A judge dismissed the disorderly conduct charge in September.)

Undeterred, Meyer returned the next week for a 24-hour vigil but decided not to sleep this time — he brought a comfortable chair instead. The week after that, he camped underneath an overpass, and he was joined by other advocates and unhoused Nashvillians.

Tennessee’s anti-camping law has its roots in curbing this type of protest. Lawmakers passed the first iteration of the anti-camping law during the 2012 Occupy Nashville protest, targeting economic activists camped out on state property with a misdemeanor crime. The punishment was escalated to a felony in 2020 in response to a 62-day campout across the street from the Capitol protesting police brutality. In 2022 the felony law was broadened to apply to all public property, with the goal of deterring homeless encampments.

A panel of service providers and advocates argued to legislators that the law would do little to actually solve homelessness, stressing the need for housing. Gov. Lee also had concerns about the bill; he didn’t sign it, but he didn’t veto it either.

In June, the United States Supreme Court ruled in City of Grants Pass v. Johnson that cities and states had the right to enforce camping bans. The decision spurred Meyer into action, and his arrest sparked headlines.

For his willingness to put himself on the line, even at age 87 — risking not just arrest but even illness and injury — in protest of a law that most experts believe will worsen the problem of homelessness rather than solve it, the Scene is naming Karl Meyer our Nashvillian of the Year. Meyer shows that a fight for justice is a lifelong endeavor, and that you’re never too old to rebel against an unfair system.

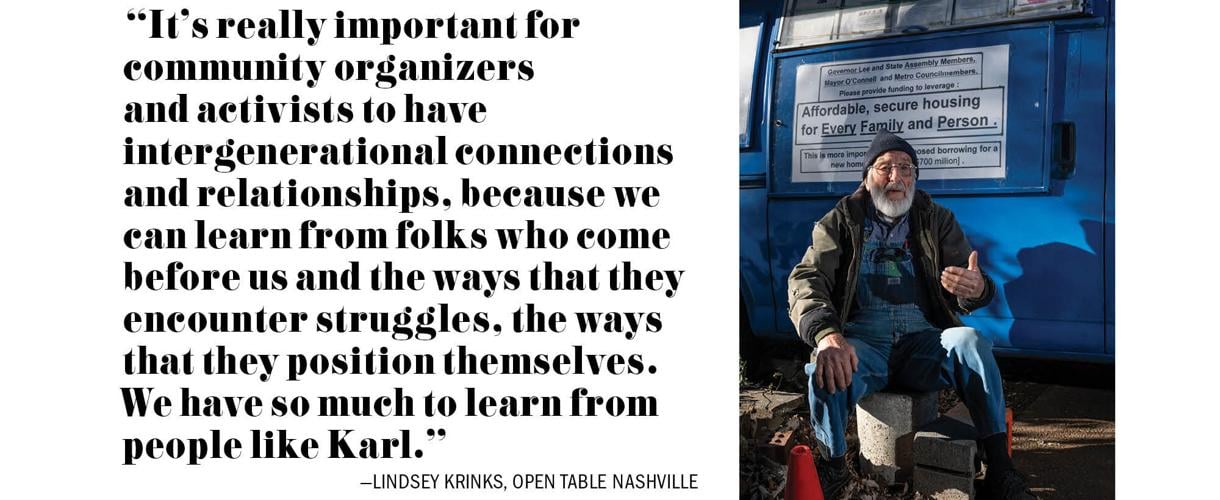

Lindsey Krinks — a friend of Meyer’s and the co-founder of Open Table Nashville, a nonprofit that serves the homeless — says Meyer’s “willingness to live out his convictions” is an inspiration, and says his protest helped keep a spotlight on issues of homelessness.

While Meyer didn’t get an audience with the governor, the concerns he raised were validated later in the year. The Scene reported state troopers arrested 10 people for public camping in November alone, mostly at Riverfront Park in downtown Nashville.

Homeless camps have also stirred controversy and debate in Nashville. Frustrated housed residents raise concerns about safety and crime in nearby camps. The city’s Office of Homeless Services has focused its efforts on clearing camps by connecting residents to housing opportunities and service providers. Homelessness advocates, for their part, worry the focus on individual camps isn’t the fairest way to allocate resources.

In Meyer’s living room is a black-and-white photograph of him at age 20 awaiting trial in New York City, circa 1958. He’s joined by four other activists, including legendary Catholic labor organizer Dorothy Day. The quintet had been arrested for refusing to participate in a mandatory citywide drill for nuclear attack — they sat outside on benches instead of seeking shelter.

It was the second time Meyer had been arrested for refusing to participate in the drills. The first time Meyer was arrested, in 1957, he served time in Rikers Island. After that, Day became a close friend and mentor to Meyer as part of the Catholic Worker Movement.

While Meyer is no longer a practicing Catholic, he still considers himself affiliated with the organization. The teachings of Day and Ammon Hennacy still influence his activism. He’s against all war, opposes the death penalty and believes in simple living and sustainable agriculture.

He’s been the subject of several profiles throughout his storied career. In 2001, University of Chicago Magazine took a deep dive into both his personal life and activist work, painting a compelling picture of a complicated radical who may have some regrets but doesn’t lack resolve.

He’s taken part in provocative actions over the past few decades. He went to Saigon to march on the U.S. embassy to decry the Vietnam War, traveled around Illinois with a mock electric chair to protest the death penalty, and smuggled Nicaraguan coffee in response to U.S. support of the right-wing Contra rebels. He has also worked with the homeless: After graduating from the University of Chicago, he set up a men’s shelter, which he ran from 1958 to 1971.

Meyer also knew many influential figures in Nashville housing advocacy, like Bill Barnes — namesake of the Barnes Housing Trust Fund — and Charlie Strobel, founder of the homeless shelter Room In The Inn. He took part in several protests since moving to Nashville, like the sit-ins against cuts to TennCare in 2005.

Meyer doesn’t expect much from the conservative Tennessee state government at this point, and is now planning to pressure the mayor and the Metro Council to focus on affordable housing. (After the passage of a sweeping transit referendum in November, Mayor Freddie O’Connell said his administration’s next priority was housing.)

Meyer sounds optimistic that his ideas would be better received at the local level, and echoes a persistent evaluation that the current Metro Council is one of the most progressive in the city’s history. His fourth and final action of the summer was held outside the Metro Courthouse, seeking to chat with Metro councilmembers ahead of a general meeting.

Meyer supports the creation of public designated campgrounds for unhoused Nashvillians and points to Green Street Church’s “Sanctuary” encampment as an example. Advocates at Open Table Nashville have also voiced support for a similar measure, but the city in the past argued that the focus needs to be on moving people into housing quickly, and that outdoor homelessness is an unsafe situation.

Like many other affordable housing advocates, Meyer thinks the Barnes Fund is an important tool, but that funding still isn’t robust enough. He also wants to see the creation of a fund that would allow the average Nashvillian to make small investments in affordable housing developments — just like his camping protest, he has his talking points written and ready for politicians.

“People can’t live in housing strategies,” Meyer says, stressing an urgent need to build homes for working-class people that reflects his history of hands-on activism.

Nashville is facing an affordable housing crisis — a report from 2021 called for the creation of more than 53,000 units by 2030. The report notes that stagnant wages will contribute to the shortage of housing in Nashville. Nationwide, homelessness is increasing as rents soar.

Meyer recalls that in the 1950s he was able to afford rent in downtown Manhattan on minimum wage. “There was much more of a safety net back then,” says Meyer, “and the safety net has so many holes in it now.”

Meyer came to Nashville in 1997, seeking a warmer climate and more affordable housing. He also wanted to engage in urban gardening and promote sustainable living. He purchased a home on Heiman Street in North Nashville in 1997. His lawn became a small farm, and he offered cheap rent in spare rooms. He called the project Nashville Greenlands.

Karl Meyer and Pam Beziat

Meyer’s partner Pam Beziat, whom he met at a Quaker meeting, bought her home shortly afterward, expanding the Greenlands footprint. Meyer and Beziat bought five other North Nashville houses over the years, creating what they call a network of homes. Ownership of several of the properties has been transferred to some of the younger activists.

Meyer admits people were surprised to see an older white man move into the historically Black neighborhood. He participated in community meetings, and he and Beziat were careful to purchase only vacant or abandoned properties.

The affordable rents offered to young folks have been Meyer’s own way of helping the housing crisis. Meyer and Beziat also contributed to the first home built by Nashville’s public land trust — a plaque outside the McKinney Street house commemorates the donation.

The Greenlands garden is still surprisingly green despite cold December temperatures. Meyer uprooted his tomato plants earlier in the week, rows of empty cages stacked like small pillars and set aside, and he bundled up a fig tree in trash bags full of old leaves to protect the tree from frost.

The garden drew the ire of Nashville’s health department during Meyer’s first years in town, with the city fining him for “excessive vegetation.” Meyer refused to scale back the garden with gas-guzzling leaf-blowers and lawn mowers. After years of run-ins, a compromise was reached, and the urban farming operation continued.

In addition to the garden, Meyer — a carpenter on top of everything else on his résumé — renovates and repairs the homes in his network.

Meyer and Beziat estimate about 200 people have come through the network of homes. Many of the guests are young activists themselves, folks who have done stints at advocacy organizations like Walk Bike Nashville, Workers’ Dignity and more. About four people are in Meyer’s home, and six next door, and Beziat has a guest as well.

Beziat says the couple help young people out by not just offering cheap rents but also helping them get started in social justice and sustainability work. Beziat is a seasoned nonviolent protester herself. She didn’t seem too worried about Meyer’s arrest this summer, noting she herself had been arrested for past protests.

“The most important thing that I can do at my age is … pass this kind of vision on to young people,” says Meyer.

One young activist Meyer and Beziat befriended is Lindsey Krinks. Krinks, who had been learning about the Catholic Worker Movement, met the couple at a protest in late 2007 and has stayed close to them ever since. When Krinks and her husband needed a new home in 2014, Beziat helped with the down payment for a house nearby, and Meyer helped set up the garden and built a shed for them. Krinks also learned a lot about activism from the couple.

“It’s really important for community organizers and activists to have intergenerational connections and relationships, because we can learn from folks who come before us and the ways that they encounter struggles, the ways that they position themselves,” says Krinks. “We have so much to learn from people like Karl.”

When the state’s camping law passed in 2022, Open Table held its own campout protest in response. One of the first people to join, says Krinks, was Meyer.

Krinks says Meyer is strategic and willing to push buttons other organizers can’t or won’t. But he’s also diligent, she says, and shows genuine care for others.

“I think it’s up to all of us to continue to live as if we can make a difference in this world with our one life,” says Krinks. “Put together, we have a lot more power than we do alone. Just one spark can transform a dark night, and that’s what I see him doing.”

Karl Meyer