A cacophony of thuds and crashes resounds through a boxy brick warehouse in Madison. It’s the sound of athletes pursuing the elegant art of lifting heavier and heavier loads of iron high over their heads, and letting them fall to ground once that task is complete.

There are no windows in the main lifting area — just wooden platforms, a clutter of weights and rows of barbells on the walls alongside various flags and banners. The smell of worn metal is in the air, and there’s no juice bar, no high-tech bikes or treadmills. This gym, the Nashville Weightlifting Club, focuses on Olympic weightlifting, and the goal is to master the two specific moves practiced in the official games: the snatch and the clean-and-jerk.

Thin metal bars are decorated with different colored plates: blue, green, yellow and red, each denoting different kilogram totals. The plates are added, removed and exchanged, but the athletes continue to repeat the same movements, aiming for flawless form. Kilograms are the language of weightlifting, as coach and former Olympian Osman Manzanares puts it. Events sanctioned by international bodies don’t let you work in pounds.

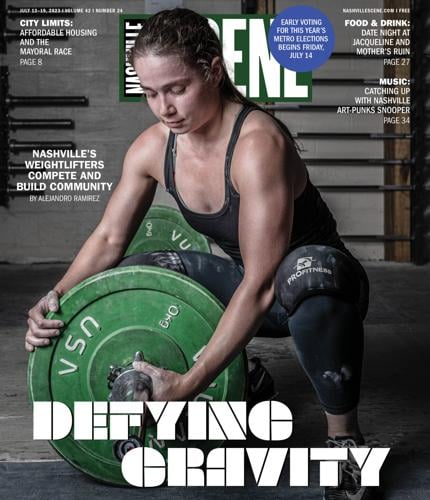

Aubrey Hutchinson has been training at Nashville Weightlifting Club for seven years. She’s already back in the gym just days after winning a silver medal at the most recent Pan American Masters competition, held in Orlando, Fla., in May. In a competition, athletes have only three attempts at each move.

She’s hard at work performing the snatch: She shifts into a squat, and swings the bar from the ground to above her head in a fluid swing. She holds for a second in a low squat, arms raised straight into the air, her balance unshifting as she stands herself upright. Manzanares smiles as Hutchinson’s form doesn’t change even as she continually adds weight.

Manzanares doesn’t hesitate to push an athlete when he knows they can do a little more. A tall man, Chris Garvey, is performing the clean-and-jerk, a motion that sees the bar raised from the ground to his shoulders in a squatlike position (clean), and pressed once more over his head (jerk), sometimes with a lunge. Manzanares shakes his head and walks over to Garvey to offer advice. He also tells Garvey to add two 5-kilogram (11-pound) plates to the bar, already adorned with at least 150 kilograms (roughly 330 pounds). Garvey doesn’t hesitate, and adds it.

Manzanares believes the extra weight will cause Garvey to focus more on the pulling motion needed to get the bar off the ground. The coach isn’t wrong, and the next clean attempt goes better. Manzanares still has advice, but he’s beaming.

“I know the training that he does,” says Manzanares. “He’s training for a lot more than that.”

Garvey has been a competitive lifter for 10 years, and has trained with Manzanares for six. He’s qualified for the North American Open Series, a national competition taking place in December in Wilmington, N.C.

Garvey continues to add weight, and completes a full clean-and-jerk. The move complete, Garvey lets the weight crash to the ground. He sits and recovers before it’s time to go again.

To the untrained eye, Olympic weightlifting may seem a bit routine. While a bar bowing under the weight of heavy plates is a dramatic visual, the subtle footwork, explosive movements from the legs and hips, and the national and world records associated with the different weights are all lost on a casual viewer.

Garvey tells the Scene that what makes the sport special is that it’s not just a matter of strength — it’s about finesse.

“You look at some of the Olympic guys … pushing 400 pounds, they’re lifting lightning-fast,” says Garvey. “It’s graceful.”

Emily Prostko, who has trained for a year at Nashville Weightlifting and hopes to qualify for a national competition, says mastering the technique is part of the appeal.

“The snatch is the most technical movement that you can do with a barbell, and because of that, it’s the most challenging,” Prostko says. “It’s a little addicting to have a constant challenge that you can never beat, because you can always put more weight on the bar.”

Manzanares has been weightlifting for 40 years, and represented Honduras in the 1992 Olympics. He was introduced to the sport around 1984, when a Polish weightlifting coach and his athletes held a seminar in Honduras during a tour of Latin America.

Manzanares, who was a bodybuilder back then, was awestruck. A Polish man smaller than himself — Manzanares is maybe around 5-foot-7 — lifted 90 kilograms, or 200 pounds. Manzanares says it was a remarkable sight in the ’80s, especially in Honduras. Manzanares tried to lift the same weight, but lacked the technique.

“That guy used to defy gravity with the weight he actually lifted,” says Manzaneres. “That’s what we do, we’re defying gravity.”

The words echo a sports medicine paper from 1970 titled “The Defeat of Gravity in Weightlifting,” which frames the sport as a battle between the athlete and physics. The lifter needs to act quickly to stand a chance against the relentless nature of gravity — hence the need for speed and finesse.

Manzanares trained. He learned the proper skills, surpassed 200 pounds (“I couldn’t believe it!”) and went to the Olympics. He didn’t medal, but he still displays his shoes and nametag prominently in the gym.

After living for years in New York, Manzanares arrived in Tennessee around 2001 to continue coaching athletes he knew from Honduras. There wasn’t a competitive weightlifting scene in Nashville at the time, he says, and he and his crew trained at odd places, like a room loaned by the Parks and Recreation Department. But they were still fearsome, world-class competitors, representing Nashville at events around the country.

Manzanares officially opened his first gym in 2009 in The Nations, and then moved to the current location in Madison in 2016. Around the time of the first gym’s opening, a trendy new fitness regimen emerged that led to more people seeking out his world-class advice. Competitive CrossFit athletes wanted to improve their weightlifting to excel in competitions and began training at Nashville Weightlifting Club.

Manzanares trains adults and youths who want to compete at the national level, but he also helps athletes looking to cross-train and build knowledge. He even coaches remotely, and — now in his late 50s — still competes himself. Manzanares says many of his athletes have started their own gyms in Tennessee and elsewhere.

Manzanares trains each person differently depending on their goals. A wrestler who wants to build strength has different needs than a CrossFitter. But if someone wants to compete in Olympic weightlifting, Manzanares needs to see two things: “The first is the willingness to train,” and the second is “the love of the sport.”

Osman Manzanares

“He loves coaching,” says Garvey. “He’s very knowledgeable, he’s very passionate, and he loves what he does.”

Nate Chung, who has trained at the gym since October, says Manzanares has a lot of insight into what an athlete is capable of. Chung also says there’s a tight-knit community fostered at the gym. “It’s super encouraging, and that vibe, you can’t really find everywhere.”

Prostko, who was part of an Olympic weightlifting team in college, also sings Manzanares’ praises. “I have gained more strength in the last year than in the three years before that.”

A few trophies in the back of the gym display some of Nashville Weightlifting Club’s accomplishments. In addition to Hutchinson’s silver at the recent Pan Am Masters, three other club members won gold. Manzanares’ own prizes decorate the club as well. At least two dozen medals hang in his office near his desk — “and not many of them are second place,” he says — and his hall-of-fame plaques from various organizations adorn the walls. He received the most recent hall-of-fame award at the Pan American Masters event in May. “They actually surprised me with that,” he says, smiling.

Manzanares’ athletes have gotten to travel to take part in competitions, including the international tournament El Criollo in Puerto Rico. Garvey says everyone seems to know Manzanares, and coaches from all over stop to chat with him at big meets — it’s a tight-knit community, especially for those with decades in the sport.

Manzanares will host a pair of USA Weightlifting-sanctioned events this year as well. The first is July 15, hosted at the gym and billed the Battle of Champions. The second is the Howard Cohen American Masters Championships on Nov. 9, which will be held in Lebanon, Tenn. (“Masters” in weightlifting refers to athletes age 35 and older.)

Manzanares says it’s the first time an event of that caliber has been held in Middle Tennessee. It’s a big responsibility, with the gym seeking sponsors and partners. But he also calls the hosting duties an honor.

The competitive weightlifting community in Nashville is small but growing slowly. It’s far easier to find boutique gyms, CrossFit clubs, high-intensity cardio programs, and even gamified OrangeTheory outposts than no-frills spots like Manzanares’. Garvey — who also sits on the Tennessee-Kentucky Weightlifting State Organization, which helps support the sport in both states — says competitive lifting gyms were easier to find when he lived in Chicago.

Weightlifting sports all emphasize different movements and goals. Olympic weightlifting focuses on technique and speed to perform its two main moves, while powerlifting emphasizes three moves — the squat, the benchpress, the deadlift — and the smaller range of motion means athletes are moving heavier weights.

But then there are the strongman competitions, which can see athletes do everything from multiple reps of a classic lift to pushing a sled loaded with weight or even pulling a truck.

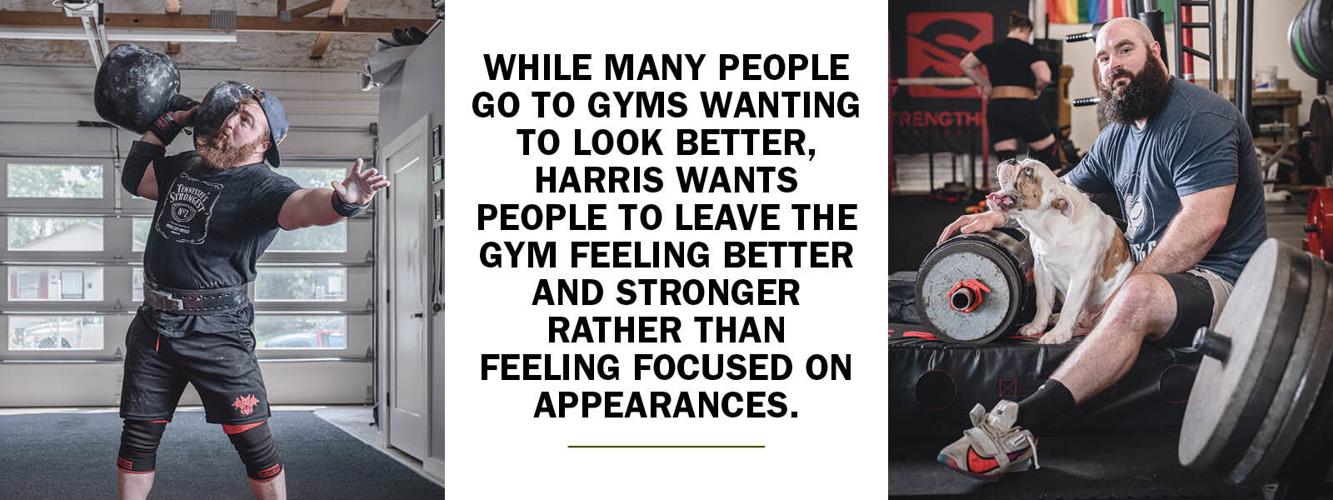

“Every other strength sport is static, meaning you don’t move,” says Blake Harris, a strongman coach and competitor. As explosive as Olympic weightlifting can be, competitors usually stay more or less in place, he says. “Whereas with strongman events, there might be a few different events where you’re actually moving with something.”

Harris adds that every strongman competition features a different challenge: “different equipment, different types of lift, what you’re lifting, how you’re lifting.” The sport even has its own accessories, like log-shaped apparatuses. In comparison, Olympic weightlifting and powerlifting focus on the same few lifts with standard barbells.

Before getting into strongman, Harris had been chasing an NFL career, and while he played professional arena football, he also worked part time at a gym. One day back in 2014, he noticed a regular coming in and training with odd equipment and doing strange exercises. Harris couldn’t help but approach the man and ask for details. It turns out he was training for an amateur strongman competition, and Harris wanted in. The contest was less than two weeks away, and although Harris couldn’t find the right coach in time, he still competed.

Harris says he “just kind of went in blind,” and still “placed six out of like 14.”

Harris had fun, and kept up with his strongman training after that. Eventually he ended his pursuit of an NFL career, but all that football training still comes in handy: He’s used to challenges that require him to move with heavy weight, like yoke carries and sled presses. Harris still competes in events, and has been hosting competitions in Nashville since 2019. He also teaches a strongman class on Sundays at the gym he owns, Music City Muscle.

Harris says that even though Nashville is “not a nitty gritty ‘strength Mecca,’” it hasn’t been hard to carve out a community of weightlifters at his gym — which is open to everyone, not just strongman athletes.

Harris says the biggest hurdle facing the sport is its name: strongman. He tries to demystify the sport for new participants. “Even the name itself would almost lead people to think that they’re not strong enough to do it, when that’s really not the case at all.”

Harris is not just a competitive coach but also a personal trainer. While many people go to gyms wanting to look better, Harris wants people to leave the gym feeling better and stronger rather than being focused on appearances.

“It’s … helping people get into a performance mindset and celebrating what our bodies can do instead of being so stuck in our heads about what it looks like,” he says.

A Dua Lipa song blares from speakers at Music City Muscle one Saturday in June, the early-morning sun lighting up the gym through its massive windows. Rainbow decorations are strewn about, and a line of shimmying people take turns stepping up to a bar loaded with weighted plates, pulling it off the ground and past their knees in a deadlift. There’s applause every time someone steps up to the barbell, and the crowd cheers every time the bar goes up and clanks back down. Participants go to the back of the line after a successful lift, readying themselves for an increase in weight, or to tap out if the load becomes too heavy.

It’s a Pride Deadlift Party, benefiting local LGBTQ causes Trans Aid Nashville and Oasis Center. Local trainer Barbara Puzanovova organized it, modeled after a similar fundraiser she saw in Seattle.

Under her brand The Non-Diet Trainer, Puzanovova has worked with women — especially women who have experienced eating disorders — to help them build strength and confidence. Puzanovova isn’t a competitive lifter herself, but she enjoys strength training, and meets with clients regularly at Music City Muscle.

The message most women receive about fitness, says Puzanovova, is that “exercise is for you to get smaller for you to burn calories. I find that a really boring reason.”

Inclusivity is a big problem in the fitness world, says Puzanovova — though it’s not necessarily because gyms are outright prohibiting people. “There is a big difference between saying all are welcome here, and then also making sure that the spaces are actually welcoming,” she says.

Puzanovova says she’s seen that among Nashville’s competitive and noncompetitive weightlifters.

“We will cheer just as much for you if you’re lifting something that feels heavy for you [instead of] only cheering for you if you’re lifting something that’s over X amount of pounds,” she says.

One of the participants at the Pride Deadlift Party — Ali Wine, who also trains with Puzanovova — echoes the sentiment.

“The reason that strength training appeals to me is really at the end of the day, you’re just competing against yourself,” she says. “You have a defined number that you work towards, and you grow, and [build] up your strength.”

Weightlifting is all about progress, and no one starts at moving a record-breaking amount of pounds, whether that’s strongman, powerlifting or Olympic weightlifting.

Emily Prostko, back at Nashville Weightlifting Club, says the first step toward success is “being humble enough to just sit down and learn the technique,” even if that means lifting an empty bar for a while. That’s where even the top competitors in the country began.

“They all started out with an empty bar — everyone did.”

Emily Prostko