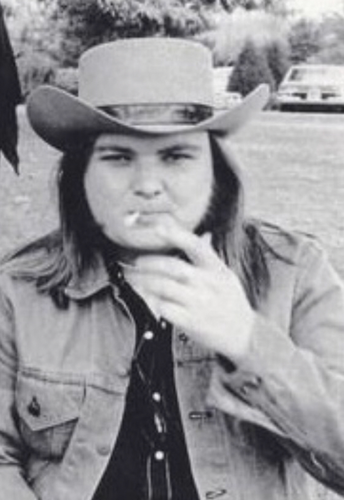

Ed King

Psych and Southern rock guitarist, expert gourmet

Ed King

That’s Ed King’s voice you hear counting down before his iconic introductory guitar riff in Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Southern anthem “Sweet Home Alabama.” He was co-writer of the song, and music royalties plus licensing rights to interstate signs and license plate mottos in the Yellowhammer State pretty much supported King for the rest of his life, which ended on Aug. 22. A rarity as a California boy who hit it big in the world of Southern rock, King first exploded on the music scene as part of the ’60s West Coast psychedelic rock act Strawberry Alarm Clock, best known for the hit “Incense and Peppermints.”

That’s right, the same musical genius behind that particular piece of trippy acid pop also contributed some of the greatest guitar leads ever wrung violently out of a Les Paul. But Ed was exactly that kind of delightfully complicated dude. Private and a bit introverted, he was always warm to his many fans on social media, although his acerbic political commentary occasionally landed him “in Facebook jail,” as he put it. He was a passionate and opinionated foodie, even after a heart transplant in 2011 resulted in an unfortunate side effect: “I don’t know if my donor had something wrong with him,” Ed shared, “but I can’t stand Italian food anymore, and I used to love it!” A fan of fresh ingredients and plates that weren’t too cold, King was a regular at both The Catbird Seat and hole-in-the-wall Guatemalan joints.

Tired of the road, King spent his last years sticking close to his lake house with his wife Sharon and his beloved English goldendoodles. (A restaurant that wasn’t dog-friendly was not considered for his regular rotation.) A fitting coda to his life was his contribution to two recent well-received documentaries, 2013’s Muscle Shoals and this year’s Showtime doc If I Leave Here Tomorrow: A Film About Lynyrd Skynyrd. In both films, the intelligent directors turned to King whenever they needed a great storyteller to share a particular memory, and King delivered the goods eloquently and with humor. In the end, that’s an excellent legacy for this songwriter and guitar picker. Chris Chamberlain

Hazel Smith

Songwriter, journalist, publicist and country music’s moral compass

Kitty Wells may have been the queen of country music, but Hazel Smith was mother of Music Row. Smith, who died of heart failure in March at age 83, was one of the few constants in an ever-changing industry for more than half a century. The beloved icon was an outspoken and colorful woman with country grammar, and each conversation with her provided a lesson in music history. (Indeed, she thought everyone who worked in country should know the words to Roy Acuff’s “The Great Speckled Bird” by heart.)

Smith was, first and foremost, a country fan, and she never stopped relating to the working people for whom country music was originally made. The farmer’s daughter moved from North Carolina to Nashville in the 1960s when she fell in love with Bill Monroe and inspired him to write “Walk Softly on This Heart of Mine.” That relationship didn’t last, but her love affair with Nashville sure did.

The divorced mother of two supported herself as a songwriter, publicist, manager, journalist, cookbook author and CMT personality. She coined the phrase “outlaw country” in 1973 while publicizing Waylon and Willie, Kinky Friedman, and Tompall and the Glaser Brothers. “One day, I was just sitting in the office, and there was an old blue Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary just laying there,” Smith told me in 1997. “It said that ‘outlaw’ meant virtually living on the outside of the written law. It just made sense to me, because Owen Bradley and Chet Atkins were doing marvelous music, but this was another step in another direction.”

She played a role in building the careers of Brad Paisley and Garth Brooks and made home-cooked meals for everybody who was anybody at her Madison home, which she bought in 1979 after Dr. Hook recorded eight of her songs. She didn’t hesitate to let the singers know — usually in print — when they made a misstep.

The slicker country music became, the more precious Smith was to Music Row. She was its moral compass, a stern but loving matriarch who was often unhappy with the direction of her favorite genre. “The songwriters now come dragging in about 9:30 a.m. wearing clean clothes,” she told me. “They’ve slept all night in their very own bed in their very own home beside their wife and not somebody else’s wife. They haven’t been chasing somebody at the Holiday Inn. I don’t know how they get their material.”

“Instead, we’ve got people writing songs who have college degrees. ... There ain’t nothin’ wrong with education, but I’d a whole lot rather hear a song with feeling to it than a bunch of educated words written from the neck up that had no feeling at all. Songs with feelings are what make us unique and what we are today.”

I asked her once why she had never remarried. “Because I love Bill Monroe,” she told me, “and he loved the world.” No wonder she understood country music so well. Beverly Keel

Roy Clark

Guitar wizard, Hee Haw co-host

Word of Roy Clark’s death in November at age 85 prompted an outpouring of memories from fans around the globe, and sent plenty down an immensely rewarding YouTube rabbit hole. In addition to being a Country Music Hall of Famer and Grand Ole Opry member, the titan of guitar was a much-loved all-around entertainer who co-hosted Hee Haw with Buck Owens and frequently appeared on other TV programs.

Clark grew up in Washington, D.C., and started performing in his early teens at square dances with his father. Winning a national-level banjo competition earned him an opportunity to play on the Grand Ole Opry, but he didn’t fully commit to being a musician until a few years later. He spent much of the 1950s touring in country bands, and an extensive stint performing and recording with Wanda Jackson in the early 1960s helped him break through and establish himself as a top-billed artist. He won multiple CMA Awards, including Entertainer of the Year in 1973, and a Grammy for his 1981 recording of “Alabama Jubilee.”

You can watch hours of clips of Clark picking and grinning without seeing the same one twice, but one in particular is a neat metaphor for his life and work: During a performance of “Folsom Prison Blues” with Johnny Cash on Hee Haw, Clark flips his guitar face-up like a lap steel and picks up a pint glass, which he uses like a slide as he hot-dogs a solo. It’s played for laughs, but it also showcases musicianship of the highest order. Stephen Trageser

Roy Wunsch

Country music executive and philanthropist

The sleek headquarters, celebrity-studded award shows and mega-deals that mark the country music industry today give little hint of its humble origins — derided within and outside of Nashville as a bunch of hillbilly bumpkin pickers. Label offices in small Music Row bungalows were regarded as nothing more than a department of the New York or L.A. parent company. Roy Wunsch came to CBS Nashville in 1975 to lead Epic Records’ promotion team, working with Tammy Wynette and George Jones. In 1981, he became the first Nashville label executive to be named vice president, and eventually president — another first. While always respecting the authentic roots of the genre, he embraced sophisticated marketing strategies for projects like Willie Nelson’s groundbreaking 1978 Stardust album, produced by Booker T. Jones. In her eulogy to the man who signed her to the label in the late ’80s, Mary Chapin Carpenter called Wunsch “utterly disinterested in his own profile in a town full of enormous egos.”

“He always hung back and allowed others to shine,” said Carpenter, “championing those who the spotlight adored as well as those who were quieter in their artistic journeys.” Those whose artistic journeys were challenged by poverty also received a boost from Wunsch, a devoted supporter of the W.O. Smith School of Music, where he established the Roy Wunsch “Stardust” Scholarship.

Diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2008, Wunsch went on an around-the-world trip with wife Mary Ann McCready, and in 2012, began painting with his artist daughter Cindy Wunsch Bowen. His first exhibition was titled Color Me Happy. Wunsch, said Carpenter, led a life of optimism, and would say: “Feel everything. Show your heart. Listen to the music. Love this world.” Kay West

D.J. Fontana

Drummer

Drummer D.J. Fontana played on some of the most famous — and most imitated — recordings in history. Born Dominic Joseph Fontana in Shreveport, La., on March 15, 1931, he became a fan of Stan Kenton’s big band and eventually landed a spot on the Shreveport country-music radio show The Louisiana Hayride. He first appeared on the program hidden behind a curtain, as the Hayride producers deemed it prudent to introduce drums to their audiences only in careful stages.

Fontana backed up Elvis Presley when the singer appeared on the program in October 1954. He joined Presley’s band, and that’s how Fontana came to show off his chops on Presley’s historic 1956 recordings “Heartbreak Hotel,” “Hound Dog” and “Don’t Be Cruel.” Fontana worked with Presley until 1968, when the drummer began playing sessions in Nashville. His formula for working with Presley was simple, as he told interviewer Dan Griffin in 1999: “I said, ‘Best thing for me to do is get up there and not get in the way. Don’t play no crashes, no noise.’ So I just played real easy, just a little rhythm. It worked out fine.” Edd Hurt

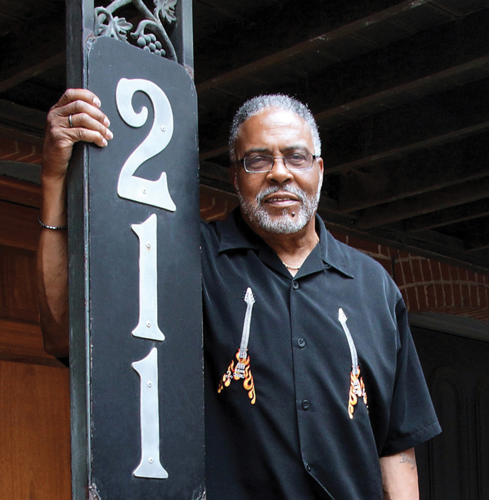

Nick Nixon

Keeper of the flame for black music in Nashville

Nick Nixon

James “Nick” Nixon was always reluctant to sing his own praises, but anyone who ever heard him play or sing would quickly do so on his behalf. Over five-plus decades, Nixon, who died in February at 76, made major contributions to Nashville’s blues, soul and gospel traditions.

Despite his background singing in church and being tutored by an opera instructor, Nixon’s greatest love was the blues. He was a wonderful guitarist who didn’t need gimmicks or exaggerated volume to demonstrate his brilliance, and he was equally masterful as a vocalist, skilled in technique and as a storyteller. Above everything else, Nixon was devoted to Nashville, spending most of his career here, rather than in Chicago or Memphis, places considered more amenable to his style. Along with his cousin Marion James, Nick Nixon wanted the world to know that Music City was genuinely a place for all styles.

“My hope is that one day everyone will know about this legacy and history in Nashville that is so great,” Nixon once told me. “I played a role in it, and I’m proud of it, but it’s even more important that the generations behind me honor and remember it. It shouldn’t be forgotten or overlooked.” Ron Wynn

Lari White

Country songwriter, producer and actor

On Jan. 23, the country music community mourned the loss of singer-songwriter, producer and actress Lari White, who died at age 52 following complications from advanced peritoneal cancer, which she’d been diagnosed with in September of last year.

White was active as a country singer and songwriter from 1988 until her passing. She made her debut in 1988 with the single “Flying Above the Rain,” eventually releasing her debut album, Lead Me Not, in 1993. Her biggest country hits include “Now I Know,” “That’s My Baby” and “That’s How You Know (When You’re in Love),” all of which appear on her 1994 sophomore album Wishes. Over the course of her career, White notched six Top 20 country hits. Her final release was 2017’s two-disc EP Old Friends, New Loves, which she put out on her own Skinny WhiteGirl record label.

White was best known as a songwriter, but she also lent her talents in the recording studio and on the big screen. As a producer, White worked with Toby Keith (2006’s White Trash With Money), Billy Dean (2004’s Let Them Be Little) and Shawn Mullins (2015’s My Stupid Heart). She played a small but important film role alongside Tom Hanks in 2000’s Cast Away and also made an appearance in 2010’s Country Strong. Brittney McKenna

Daryle Singletary

Country singer

All great country singers start out by trying to clarify their relationship to the tradition of country singing, and Daryle Singletary made connections to the tradition that left no doubt about how easily he fit into it. The plainspoken and unpretentious singer became a star by virtue of his hits, which he recorded in the ’90s, during the interim period in Nashville between Randy Travis’ new traditionalism and Shania Twain’s genre-busting late-’90s dance pop.

Daryle Singletary was born in 1971 in Georgia, and he grew up listening to gospel and to George Jones. He moved to Nashville in 1990, sang demos, and hit the charts later that decade with neo-traditional songs like “Amen Kind of Love.” A first-rate exponent of traditional country singing, Singletary skillfully imitated Jones in the 2002 track “That’s Why I Sing This Way,” from the album of the same name. That’s Why I Sing This Way, a collection of cover versions cut after the hits dried up, is his testament. He sang that way because he loved to, and his affair with country music was, in every way, a healthy relationship. Singletary died on Feb. 12 in Lebanon, Tenn. Edd Hurt

John. T. Benson III

Gospel music executive

John T. Benson III, who died Oct. 28 at age 90, was a longtime leader of the Gospel Music Association, continuing a formidable family tradition within gospel while expanding its commercial success and musical reach.

The Benson Company, Music City’s oldest permanent music business operation, was already well-established in Southern gospel when Benson joined the family firm in 1969. But he brought it new fame and clout as an executive through his role in the growth of the contemporary Christian music movement. During the ’70s and ’80s, he signed many acts and performers to publishing and recording contracts before they became superstars. He also brought in black acts like Yolanda Adams and Larnelle Harris, embracing diversity long before it became a major cultural issue.

The Benson Company’s 1976 move to a Metro Center building made the business, at the time, both Nashville’s biggest music headquarters and the place housing its largest recording studio. A 2006 Gospel Music Hall of Fame inductee, Benson oversaw the creation of Gospel Music Week during his tenure as GMA president, and his impact on the modern gospel sound cannot be overstated. Ron Wynn

Jamie Simmons

Hard rock hero, husband, father and brother

Jamie Simmons

The story of Nashville’s punk and New Wave scene in the ’80s has been well and rightly remembered. But when Jamie Simmons died at age 49 in February, the city lost a link to a key element of local music history. He grew up watching his older brothers, guitarist Mike and drummer Paulie, hone their hard rock chops, and they recruited him when he was just 16 to play bass in a group they’d formed with singer Cash Easlo. An earlier version of the band was called Assault, and was one of the first local metal acts to build a following around original material that took cues from heavyweights like Dio and Iron Maiden.

With the addition of Jamie, the band morphed into Simmonz, and his rock-solid playing was a foundation for a tower of bared-teeth riffs, Gatling-gun fills and blood-curdling wails. Maybe Simmonz never became a household name, but it helped pave the way for a whole segment of the city’s rock scene. The band members maintained close ties to other segments, too: Simmonz was near the top of the bill at the 2012 memorial concert for the late Jason and the Scorchers drummer Perry Baggs.

Outside of his work as a musician, Jamie Simmons is remembered for offering that same stability and dedication to his family and friends.

“He was such a huge presence in the lives of those he loved and those who loved him,” says Mike Simmons in an email. “Paulie and I loved him so much, and we were so lucky to be able to grow up and play music together for so long. He loved his wife and daughters so much — he was the best father and husband I ever knew. He was so devoted to them. Jamie had such a beautiful spirit. Ask anyone who knew him. I’ll never forget his smile. It was such a beautiful, comforting smile. And his laugh. I can close my eyes, picture it, hear it, and he is still here with me.” Stephen Trageser

Denise LaSalle

Champion of the blues

Denise LaSalle

Denise LaSalle made salty blues and risqué soul her trademarks, but she was also a dynamic entertainer and underrated vocalist. LaSalle, who died Jan. 8 at 83, enjoyed one signature hit with the 1971 anthem “Trapped by a Thing Called Love.”

Many artists of her generation struggled to find an audience during the ’70s and ’80s, when commercial black music was dominated by funk, disco and the coming of the urban contemporary sound. But LaSalle remained relevant by championing songs that could be edgy, provocative, humorous or fiery, sometimes combining all those elements into one tune. Her singles and albums for the Mississippi-based Malaco label remained reliable sellers among an older demographic, but LaSalle wasn’t content just to reach her base. She founded the National Association for the Preservation of the Blues in 1986, and constantly toured with both veterans and newcomers on the soul/blues circuit, fighting to ensure that the sound she loved wouldn’t be forgotten or abandoned.

LaSalle was a 2011 Blues Hall of Fame inductee, and until her health failed, she stayed on the road, content to keep singing and spinning the bawdy tales that made her a latter-day queen of the blues. Ron Wynn

Randy Scruggs

Guitarist, songwriter, studio owner

The concept of progressive music has always been vexed in Nashville. There is a strong streak of conservatism in country and bluegrass, genres usually associated with Music City. Still, both forms have their avant-gardes. In his quiet way, Nashville guitarist and producer Randy Scruggs pushed country and bluegrass in new directions, and he did so as part of one of the most storied families in country music.

He was one of three sons of famed bluegrass banjo innovator Earl Scruggs, himself a notably forward-looking musician. Along with his brother, Gary, Randy upheld country traditions while exploring rock and jazz.

Randy Scruggs was born in Nashville in 1953. He learned autoharp when he was 6 and guested on Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs’ television show when he was 9. A superb fingerstyle guitarist who could also play rock, Randy made his mark as a songwriter, a session guitarist and a studio owner. The winner of numerous Grammy and Country Music Association awards, Randy played on records by Rosanne Cash and Emmylou Harris, and he released a 1998 solo album, Crown of Jewels, that demonstrated the breadth of his talents. He died in Nashville on April 17. Edd Hurt

Eric Lee ‘Erik’ Holcombe

Punk and metal standard-bearer

Erik Holcombe

Erik Holcombe played with some of the loudest, most intense bands to come out of Music City over the past quarter-century. Sadly, he took his own life in April at age 37, and Nashville’s punk and metal scenes lost one of their most ferocious and dedicated exponents.

The Alabama native was known for hardcore punk bands like Fecal Matter, which he started with his brother Roger when they were students at Mt. Juliet High School, and Booby Hatch, which played the final show at Lucy’s Record Shop before the underground music hot spot closed in 1998. He might have been best known as the frontman for the much-loved thrash outfit Asschapel, a group that was immortalized with a reissue of its complete discography by connoisseur heavy-music label Southern Lord.

Most recently, Holcombe played bass in two incarnations of the Mötorhead-inspired trio Hans Condor, with singer-guitarist Charles Kaster and (during the band’s second run) drummer Ryan Sweeney. The week after Holcombe’s death, Kaster and Sweeney both wrote remembrances of their friend and bandmate for the Scene.

“He was one of the most intelligent and hilarious people I’ve ever known,” wrote Sweeney. “He was so quick-witted and loved a dumb, smartass joke. We laughed till we were in tears all the time in the Condor van. We had the best time together.”

“Erik fixed every broken guitar, every broken amp and every broken van, and never complained about it one bit,” Kaster wrote. “When he talked, when he worked, when he toured, when he wrote, when he played the bass ‘like a fat boy fartin’ through a hollow log,’ I was a sponge, learning all I could about how to be more like him. As I write this, I am crying, fighting against the black hole of would’ve, could’ve, should’ve. He was my friend, rock ’n’ roll brother, and most importantly, my mentor. I love you Erik Holcombe. God damn it, man, I hope you know I love you.” Stephen Trageser

Tony Joe White

Singer, songwriter and soul legend

Tony Joe White

Tony Joe was a true original, a soulful guy who had a vivid imagination and was one of the greatest songwriters ever — his songs were like a movie in three minutes. He was able to say a lot with very few words, and the colorful characters he wrote about, which were based on real people, were larger than life: “Willie and Laura Mae Jones”; “Roosevelt and Ira Lee”; “The High Sheriff of Calhoun Parrish”; “Old Man Willis”; and of course, “Polk Salad Annie.”

T.J. used nicknames for several of the musicians who played with him. Marc Cohen was “Boom Boom.” Jack Bruno was “Swamp Man Jack.” Rick Reed was “Snake Man.” Tyson Rogers was “Moogy Man.” And I (his drummer) was “Fleetwood Cadillac.” I loved that nickname! T.J. used to tell crowds he’d gone down to the state mental hospital in Mississippi — the “state home,” he would call it — to get me out to do a tour, saying he’d have me back in a few days. My attendant would have to remind him to keep me on my meds, he’d say. Onstage T.J. would turn around to look at me and tell the crowd, “I think he’s doing all right so far.”

We had many gigs that were magical. He had some seriously hardcore fans and was always generous with his time with them. Early in his career, his song “Soul Francisco” had become a big hit in France. His French audience stuck with him throughout his whole career. European and Australian audiences in general were always bigger than the U.S. audiences, but he had hardcore fans everywhere he went.

The last gig we played together was at the City Winery in New York City — it was a fun night, and T.J. was in great form. The next day we did a radio show that was filmed, and the day after that he made his Grand Ole Opry debut. I love the thought of T.J. giving the Opry crowd a dose of funk, and I know he was excited about that. It was a great honor for me to know him and to play music with him — he had a forever-young attitude about music, and he loved getting out on the road and playing gigs. Tony Joe was 75 years old when he passed, and he left the world way too soon. Play on, brother! Bryan Owings

Glenn Snoddy

Recording engineer, studio owner and sonic innovator

Seldom does one person’s career touch on so much music history as that of Glenn Snoddy, who was 96 when he died in May. The Shelbyville native was a decorated U.S. Army veteran who studied radio and recording technology while he served during World War II. After the war, he took on a steady succession of jobs in Nashville’s burgeoning music business, including running sound for the Grand Ole Opry and engineering at Castle Studios, the first major commercial studio in the city (and the place Hank Williams recorded).

Later, Snoddy worked his way up to become chief engineer at producer Owen Bradley’s Quonset Hut Studio on Music Row. During the 1960 session there for Marty Robbins’ “Don’t Worry,” he had the foresight to recognize something exciting in an event that others probably would have brushed off as an annoyance. A channel on the mixing console malfunctioned, adding an uneasy growling tone to the sound of session player Grady Martin’s bass guitar. Not only did Snoddy and producer Don Law keep the fuzzed-out take, but Snoddy also designed a device to reproduce the effect at the tap of a foot. The Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone sold modestly at first, but became wildly popular after Keith Richards used it on The Rolling Stones’ 1965 hit “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” — setting the template for popular musicians to experiment with an ever-growing array of electronic sounds.

You might conclude that Snoddy had a gift for recognizing the underappreciated, though he wouldn’t agree in every case. He hired Kris Kristofferson as a janitor, but as he told The Tennessean in 2013: “I hired him to clean up the studio. What did I know about songwriting? Not much.” But there’s no disputing he knew recording and studio design. In 1968, he opened Woodland Sound Studios in East Nashville, where (among many others) The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band recorded, cutting the landmark album Will the Circle Be Unbroken with an array of country legends. Besides his family and friends, Snoddy leaves behind decades of inspiration, innovation and top-quality work. Stephen Trageser