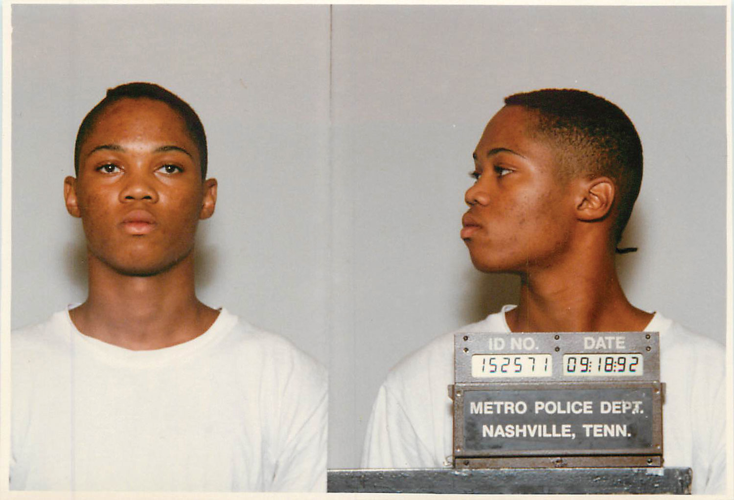

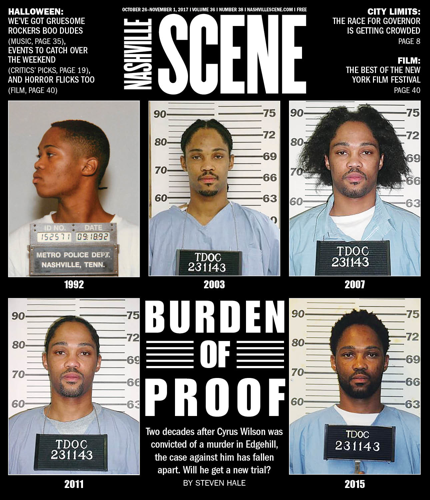

Cyrus Wilson in 1992

Cyrus Wilson is led into Courtroom 6D of the A.A. Birch Building downtown, wearing a blue Tennessee Department of Correction uniform. His hands are shackled in front of him and his eyes are scanning the gallery from behind a pair of glasses as he takes his seat in front of Judge Seth Norman’s bench for a hearing Monday, Oct. 23.

He raises his cuffed hands and smiles at his wife, Casey, who is seated in the front row, surrounded by family and friends who have come to show their support. They believe what Wilson has maintained for 25 years. They believe that he is not a murderer.

Wilson, now 43 years old with flecks of gray in his hair, was 19 in February 1994 when a jury found him guilty in the shooting death of another Edgehill-area teenager. The trial lasted just two days. It was Norman, the 83-year-old judge now looking down at him from the bench, who read Wilson the verdict and handed down his life sentence. Wilson has always insisted that he was innocent of the crime, and now, more than two decades later, the original case against him is evaporating.

In 2013, two of the state’s witnesses — one of whom was supposedly an eyewitness to the murder, both of whom were juveniles at the time — recanted their original testimony, claiming they had lied after pressure and threats from prosecutors and Bill Pridemore, who was then a Metro Nashville police detective and is now serving his second term on the Metro Council. On this morning, two more witnesses are in court making the same claim.

Wilson looks on as one of the recanting witnesses, Marquis Harris — who was just 14 when he testified at the original trial — shuffles up to the stand.

“I told them what they told me to say,” says Harris, explaining his original testimony.

Defense attorney Jesse Lords asks him if that testimony was the truth.

“No, it wasn’t true.”

The murder of Christopher Luckett took place on the night of Sept. 15, 1992, in the Edgehill area, a predominantly working-class neighborhood of public housing and apartments between what years later would become the Gulch and 12South. It was one of 89 homicides in Nashville that year, and it came as the national murder rate was still hovering near its historic peak. As the nation’s politicians were offering up tough-on-crime policies as a bulwark against the violence dominating headlines, fear and distrust of the police among black Nashvillians was becoming a more prominent factor in city politics.

Luckett, a thin African-American teenager who stood around 5-foot-7, was known as “Crip,” a nickname he acquired after a car accident left him unable to use his right arm and right hand. He died the day before his 20th birthday.

Shortly before midnight on that cool September evening, Metro police responded to a shooting call from the 1400 block of 11th Avenue South. When they arrived, they found Luckett partially underneath a chain-link fence, dead from multiple gunshot wounds. Crime scene photos show him lying on the ground in a black Michael Jordan T-shirt, the left side of his face ripped away, his hands mangled and an inch-and-a-half-wide gunshot wound in his chest.

Two days later, police arrested Cyrus Wilson, who had just turned 18. In his mugshot, Wilson appears slight and straight-faced. The photo, and those that show the dead boy he was accused of killing, make for an uneasy fit with the term “young men.” They look like kids.

The following February, Wilson was indicted in Luckett’s death, and a year later he stood trial for what prosecutors portrayed as a vicious revenge killing. The use of DNA testing in criminal cases was still years off, and the police had made no attempt to take fingerprints from a duffel bag and shotgun shells found at the scene, citing damp conditions. The prosecution’s case against Wilson relied on circumstantial evidence and the testimony of juvenile witnesses.

Metro Police Officer Andy Wright testified that almost two months before the shooting, Wilson had told a Metro police officer that Luckett had stolen his car at gunpoint. Later, according to the officer’s testimony at trial, when Wilson and the officer recovered the ’68 Chevy Bel Air, it had been stripped of its tires, wheels and a stereo system that Wilson said was worth more than the car itself.

Two of the teenage witnesses testified that Wilson had been upset with Luckett over the car theft and had said he was “going to get” Luckett. Particularly crucial to the case, though, were the accounts of two boys who said they had witnessed the shooting. In hindsight, their testimony at the trial appears to foreshadow questions about the case that would arise decades later.

Rodriguez Lee, who was 16 at the time of the trial, had been friends with Wilson and gone to school with Luckett’s sisters. The state called him as one of its key witnesses, but as recorded in a court transcript of the trial, it appears that at first his testimony doesn’t go as Assistant District Attorney Kymberly Hattaway expects. She asks Lee if he was with Wilson on the night of the murder. He says no. She asks if he remembers the day Luckett was killed, to which he says yes, but when she returns to the question of whether he was with Wilson on that day, he again says no.

Hattaway approaches from a different angle, eventually arriving once more at the question of whether Lee saw Wilson on the night of the murder. He answers, again, “No, ma’am.” At this point, Hattaway asks that the jury be removed from the courtroom, then asking Lee why he apparently intended to testify to something different than what he’d told her and then-Detective Bill Pridemore, who’d investigated the murder, a week-and-a-half before. Soon she’s using questions to walk him through what he’d told them and mentioning the word perjury.

With the jury brought back in, Lee testifies to witnessing a brutal murder. He says he saw Wilson chasing Luckett with a shotgun, firing at him when Luckett reached a fence and tried to crawl under it, becoming stuck. That’s when, Lee says, he heard Luckett begging, “Please don’t kill me,” as Wilson cocked the shotgun and shot him in the chest. Luckett put his hands up toward the barrel of the gun, Lee says, and again begged for his life, when Wilson fired again and “shot his fingers off.” He fired once more, Lee says, shooting Luckett in the face.

On cross-examination, Wilson’s attorney John Blair questions Lee about his initial statement to police — one previous to, and different from, the one to which Hattaway had been trying to hold him. Two days after the murder, Lee had told police that he saw Wilson and another man, Benji Amos, chasing Luckett. But it turned out Amos had been in jail on the night of the murder and could not have been at the scene. Moreover, Lee had told police that he saw Wilson put the shotgun in the trunk of his car after the murder, but the defense said Wilson’s car had been parked, undriveable, in another part of town.

The next day, the state calls Marquis Harris, then 14 years old, to the stand. His testimony is filled with stops. Asked multiple times by the prosecutor if he’s nervous and afraid to be there, he says yes. At one point, presiding Judge Seth Norman offers to help him along. Ultimately, he testifies that he heard gunfire from his apartment and watched from his bedroom window as Wilson shot Luckett. He also testifies that he saw Wilson after the shooting with blood on his clothes.

Wilson’s girlfriend at the time testifies on his behalf, and then, against the advice of his attorney, Wilson takes the stand himself, maintaining his innocence. According to the transcript, he says he had been at the Hillside Avenue apartment complex where he lived when he heard the gunshots. At one point, the prosecutor, Hattaway, asks him: So everybody who’s testified that they saw you with that shotgun is lying?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Wilson says.

The jury didn’t believe him. After a trial that lasted just two days, they unanimously found him guilty of first-degree murder.

“Mr. Wilson, you have heard the verdict of the jury,” the judge said, as Wilson stood before him. “The jury has found you guilty of murder in the first degree. It is my duty as the trial judge in this case to sentence you to the penitentiary for life.”

Wilson has been in prison ever since. But now, 25 years after his arrest, four of the witnesses whose testimony sent him there have come forward to say he was right that day in court. They’ve come forward to say they lied.

Casey Wilson was 17 years old in 1993 when she and her cousin accepted a collect call from the Nashville jail. After a while, she says, the incarcerated man on the other end of the line said that his friend — another man locked up downtown — wanted to talk. Casey got on the line and heard 18-year-old Cyrus Wilson’s voice for the first time.

“You’re in jail?” she remembers asking him. “Why are you in jail?”

He told her he’d been arrested for killing someone but that he didn’t do it. His attorney was working on it, she remembers him saying, and he didn’t think he was going to go to prison.

Because she was still a minor, she couldn’t go visit him, but they began writing letters. Occasionally, Wilson would call his mom, who would call Casey to set up a three-way call. He couldn’t call Casey at home, she says, because “at that point in time my mom didn’t know I was talking to the guy in jail.”

When she turned 18, Casey would go to see him in person, the two of them sitting on opposite sides of a glass partition, ignoring the phone handset on each side and talking through holes that visitors had made in each cubicle over time. He would assure her, she remembers, that everything was going fine. His attorney was working on it. He was innocent, he said. And she believed him.

In hindsight — and with the benefit of experience from her current job as an investigator for the Metro Public Defender’s Office — Casey says she sees more clearly what she describes as elements of theater in the original trial.

On a Sunday just before the trial started, she says, the prosecutor in the case, Hattaway, contacted Wilson’s mother, Valerie Ehinlaiye, and asked her to come downtown for a meeting. Casey, who had become close with Wilson’s mother, went with her and says that upon their arrival, Hattaway asked Ehinlaiye whether she had any weapons.

“No, I’m scared of guns,” Casey remembers Ehinlaiye replying.

To that, Casey claims, Hattaway responded, “Well your son obviously isn’t.”

The state subpoenaed Ehinlaiye but never called her as a witness, which Casey now believes was a strategy simply to keep her out of the courtroom during the trial.

Once the trial began, the state’s witnesses, some of whom were in custody at the time, were brought into the courtroom free of handcuffs, Casey recalls. But Wilson, having then been in jail for nearly a year-and-a-half since his arrest, shuffled in wearing shackles.

Remembering the initial photos and video of him after his arrest, Casey says: “He’s tall, but he only weighs like 150 pounds. He looks like a little boy. … Well then, two years later at trial he’s been in jail for two years, and what do you do when you’re in jail? You work out. That’s all you do. So by this time, he’s like 215 pounds, he’s pretty buff. His hair’s long, he’s got it in cornrows. You know, he looks a little scary. He fits the profile.”

Casey says that after the verdict, she felt “literally like someone kicked me in my chest — I thought I was going to pass out.”

“His mom,” she adds, “it was almost like she stopped right there, and life just stopped at that moment, and it’s never picked up again.”

Over the next 20 years, Wilson and Casey’s relationship would wax and wane, the two drifting apart, then reconnecting multiple times — until several years ago. On April 1, 2014, she took a half-day off work and drove to Riverbend Maximum Security Institution outside of Nashville, where Wilson had been moved. They were married in a short ceremony, after which they were given 10 minutes to sit with each other.

In the years since, Casey has continued to be Wilson’s biggest advocate on the outside. She’s become part of a group that has continually sounded the alarm about the poor conditions in the prisons where their spouses and partners are incarcerated. Their relationship, she says, has had a complicated, at times, disheartening effect on her life.

“A lot of people don’t understand it,” she says. “Since we got married, my circle has changed tremendously.”

From Left: Cyrus Wilson and Casey Wilson; Cyrus and Casey with her daughters Kaylee and Kassidy Greer; Cyrus and Casey with his sister, Venoice Wilson, and her daughters

Wilson has insisted that he did not kill Christopher Luckett ever since he was first accused of pulling the trigger 25 years ago, but the courts have been largely unmoved. After the original trial, he unsuccessfully challenged his conviction, citing ineffective assistance of counsel. In 2004, as a working single mother of two, Casey reached out to a now-defunct innocence clinic at the University of Tennessee for help with the case. But with no DNA evidence, it was a nonstarter. She wrote to attorney after attorney with no luck.

But in 2008, Wilson, then 33, found a thread that he believed could unravel the state’s case against him. And he pulled it.

Fifteen years after he’d asserted in court that the state’s witnesses were lying, Wilson obtained a note from one of the prosecutor’s files that had not been turned over to his defense attorneys at the time of the original trial. It appeared to cast doubt on the very foundation of the state’s case against him.

“Good case but for most of [the witnesses] are juveniles who have already lied repeatedly,” read the handwritten note.

Wilson’s petition for a new trial based on what he contended was exculpatory evidence that had been withheld from him in violation of his rights was swiftly dismissed by the Davidson County Criminal Court. But in 2011, the Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals reversed the decision, sending it back to the lower court for an evidentiary hearing.

Wilson says his attorneys were working on a possible plea deal that would have led to his freedom, but he shut that down because he didn’t want to plead guilty. Still insisting on his innocence, he continued fighting the case to no avail. In 2012, the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled that the prosecutor’s note was inadmissible in court and not sufficient to force a new trial.

Another year-and-a-half in prison. A 38th birthday.

And then, in November 2013, two witnesses from his original trial came forward to recant the testimony they’d given 20 years before. Rodriguez Lee testified at the original trial, as a 16-year-old, that he had seen Wilson chase Luckett with a shotgun and shoot him three times as Luckett was pinned on the ground begging for his life. But in 2013, he said it had all been a lie. Asked at a hearing by Wilson’s then-attorney Patrick McNally why he was coming forward, Lee says, according to a court transcript: “My conscience has been on me for a long time.” He says he had been pressured by then-Detective Pridemore and threatened with criminal charges if he didn’t tell the authorities what they wanted to hear. The affidavit he signed says the police handcuffed him when they came to his mother’s house to speak with him.

“At the time when they came to my mother’s house, they was threatening me, saying that if I didn’t tell them what they wanted to hear that I was going to be charged with the murder,” Lee says, according to the court transcript of the hearing. “And my momma told me to tell them what they wanted to hear, so that’s what I did.”

“And the facts that they wanted to hear,” McNally asks him, “where did you get them?”

“From them, from the detective,” Lee says.

During cross-examination, Assistant District Attorney Dan Hamm comes at Lee hard, pointing out Lee’s faulty math as to how old he was when he gave his first statement to the police and letting him know that he could be charged with perjury for his false statements. Hamm asks him why, in a previous discussion with Hamm about recanting his testimony, he had not told the prosecutor that the police had threatened him.

“Why would I come forward and tell you for, you is with them,” Lee responds, according to the transcript. “You on they side, basically.”

Notably, problems the prosecution had apparently been willing to overlook in juvenile witnesses providing crucial testimony for the state became pressure points into which they leaned hard once those witnesses started recanting. Hamm presses Lee about minor inconsistencies between his affidavit and statements during the hearing, as well as the criminal record he had at the time of the original trial. He also seizes upon Lee’s manner of speaking. Asked how he had contacted Wilson’s attorney McNally about his desire to recant his testimony, Lee says he’d gotten in touch with the attorney through “my sister’s little boy daddy.”

“I don’t know what that means, ‘little boy daddy,’ ” Hamm responds. “Speak English if you don’t mind.”

At the same hearing, Rashime Williams, who was 17 at the time of the original trial but had not been called to testify, also says he had lied to police about Wilson having possession of the alleged murder weapon and Wilson talking about the killing afterward.

“I put that on Cyrus because I felt like the police was trying to put something on me,” he tells the court.

Also introduced at the hearing is a Tennessee Bureau of Investigation report showing that the shotgun that police had initially believed Wilson used to shoot Luckett did not match the shells found at the crime scene. The gun had not been introduced at the trial, but the prosecution had strongly suggested it was used. At the 2013 hearing, Hamm argues that the report was of little importance, since it wasn’t new and the gun had not been introduced at trial. But Wilson — maintaining his innocence from the witness stand once more — contends that the TBI report backed up Williams’ claim that, contrary to his initial statements to police, he had actually been in possession of the supposed murder weapon the whole time.

Wilson is asked, as he had been during the original trial, if he is claiming that everyone who had implicated him was lying. He gives the same answer: Yes.

Speaking to the Scene now, several years removed from his involvement in the case, McNally says it raises issues beyond the guilt or innocence of one man.

“I hope for Cyrus Wilson that he gets some relief down the road sometime with these witnesses recanting what they testified to at trial,” McNally says. “Surely the wrongfully convicted man is a horrendous thing to happen in our society. But the greater public policy concern, is how police conduct interviews of child witnesses.

“In this case back at the time when Rodriguez Lee was interviewed,” he continues, “it was not a slow, quiet search for the truth. It was to get a statement consistent with the police theory.”

But at the 2013 hearing, the prosecutor, Hamm, dismisses the recanting witnesses as not believable.

“Your honor, there has been no new proof from the defendant,” Hamm says in his closing argument, as recorded in the transcript. “Only admissions by perjurers and convicted felons about their testimony. Quite frankly, it wouldn’t matter anyway, but there was ample proof to convict the defendant in other ways. There was other eyewitness testimony, and there was circumstantial evidence.”

The criminal court concurred, as did the Court of Appeals, which denied Wilson’s petition as well in July 2014. Four months later, shortly after Wilson’s 40th birthday, his request to appeal to the Tennessee Supreme Court was denied.

More years went by. More birthdays. Then earlier this year, two more witnesses came forward with consciences they said they needed to clear.

“I’m writing in regards to your conviction in case No. 93-A-176. I been seeking your contact information for several months now to inform you of a burden I been living with for almost 25 years and now ready to reveal. Mr. Wilson I was coerced by the detective and the assistant district attorney in your case to give false testimony at your trial and I believe you should be made aware of the state’s actions.”

That is what Marquis Harris said to Cyrus Wilson in a handwritten letter sent last year from Turney Center Industrial Complex, where Harris is incarcerated. Attached was an affidavit, laying out a story similar to the ones that Rodriguez Lee and Rashime Williams brought forward several years ago. Over six handwritten pages, Harris — who was 14 at the time of the original trial when he testified that he saw Wilson shoot Luckett to death — claims he was pressured by Pridemore and threatened with being charged in the murder himself if he didn’t tell police what they wanted to hear.

Harris writes that after a brief initial conversation following Luckett’s death, the detective and another officer returned to the apartment where Harris, then 13 years old, lived with his parents, stopping him in the hallway outside. Harris says his parents were not home, but Pridemore asked if they could speak inside the apartment. Harris writes that, with the other officer standing at the door, Pridemore began to question him. Harris writes that he started to cry, telling the officer that he didn’t know a person named Cyrus and didn’t know anything about a murder.

Further on, Harris writes that Pridemore “said I have my whole life ahead of me and there’s no need to throw it all away for a guy like Cyrus.” Harris writes that when he repeated that he didn’t know Cyrus or anything about the murder, “the detective grabbed my left arm and asked me (in a loud tone) do I want to spend the rest of my life in prison for someone else’s mistake.”

Throughout the affidavit, Harris claims Pridemore sketched out the police theory of the crime to him and told him the statement he needed to write. When the trial came, he writes, he tried to answer the prosecutor’s questions in the way he was told to, but he “was scared and nervous and what all I couldn’t remember I made up.”

“As I previously said, I knew what I was being coerced to do by the detective and the ADA was wrong but I had no control over the matter,” Harris writes. “So now after living with this burden for almost 25 years, I’m therefore coming forward with this sworn affidavit as a witness recanting my trial testimony and any other testimony or statements I made against Mr. Cyrus D. Wilson in case No. 93-A-176 because it’s false. I do not know Mr. Wilson or the alleged victim in the case. Nor did I see Mr. Wilson shoot and kill the alleged victim. The only reason I know of this case is because I was explained the details by the detective and the ADA.”

In a separate affidavit, Phedrek Davis, who was also a juvenile witness in the case, recants his trial testimony as well. In 1994, Davis testified that Wilson had spoken to him about killing Luckett, saying, “He said he was going to get him.” But now Davis says Wilson never said that to him.

Further, Davis claims that when he arrived at the courthouse for Wilson’s trial, the prosecutor showed him a newspaper article that stated Wilson had told people he was “going to get” Luckett. What he ultimately said on the witness stand, he claims now, came directly from the article after a threat from the prosecutor that he would be charged with accessory to murder if he didn’t repeat it.

In a brief conversation with the Scene before this month’s hearing, Pridemore declined to go into the details of the case or the new claims from recanting witnesses. He said he needs to refresh his memory of the case and familiarize himself with the new affidavits (which the Scene sent to him while reporting this story). But he denied ever threatening a witness to obtain their testimony.

“I’d never threaten anybody to the point of incarceration [to get them to] provide false information,” Pridemore said. “That’s not how I worked. I’d rather let a guilty man go free until I can build a case than put an innocent man in jail.”

“I’m actually happy to have the opportunity to go to the [hearing],” he added later, “because that’s not the way I worked. So I don’t appreciate the fact that some possible false statements have been made for someone else’s gain.”

But Jesse Lords, the defense attorney who took on Cyrus Wilson’s case after Casey Wilson approached him about it early last year, sees the new recantations as the last bits of the state’s original case against Wilson falling away.

“In the totality of all the proceedings so far, what I find to be a little shocking is that the case in its entirety is crumbling,” he tells the Scene. “There are so many witnesses coming forward saying not only did they lie, but they were coerced into lying by the investigating officers, by the district attorney’s office, that they were threatened with prosecution.

“These witnesses who are recanting are victims themselves, in a way. The authorities who are sworn to protect them [were] threatening to railroad them for crimes that they know for a fact that they didn’t commit in order to get them to tell, on the stand, what it is they want them to tell. That’s amazing that that could even happen.”

The victims of what occurred on the night of Sept. 15, 1992, start with Christopher Luckett and go out from there. His parents, robbed of their son; his sisters and brothers, stripped of a sibling in a horrific manner. The list goes on, and among the departed are however many decades Luckett would have lived if they had not been wiped away on the dewy grass that night. The Scene reached out to the Luckett family about this story, through District Attorney Glenn Funk, but they have so far declined to comment about the case.

The question that remains is whether Cyrus Wilson is a victim too. Whether he is the victim of cops cutting corners to get a conviction, ruthless prosecutors and a broken justice system, and whether decades have been unjustly taken from him too.

Speaking to the Scene by phone from Trousdale Turner Correctional Facility in Hartsville, Tenn., less than a week before the hearing in Nashville, Wilson sounds neither hopeless nor optimistic about his prospects. The years have taught him, he said, that the system — at least in its current configuration — is not designed to work for him.

“I’ve been conditioned to understand that no matter what my position is and no matter what I can present to them in terms of proof of my innocence, they’re just not prepared to embrace it,” he says.

He described the attitude with which the police and prosecutors approached his case 25 years ago in stark terms.

“I was young and black and poor, and nothing else matters,” he says. “My innocence didn’t matter, my future didn’t matter.”

Although his insistence on his innocence made his conviction a shock, he says, it has also sustained him over the past two decades. Beyond his own case, he says he is motivated to fight a system that wreaks havoc on millions of Americans, many of them black.

“I’m not the only one. I’m certainly not the only one who’s experienced what I’ve experienced.”

People who are incarcerated — even those who aren’t innocent, he said — have often been mistreated by the system. It’s a system, says Wilson, that is run by those who seek to punish people for political gain, to bury criminal defendants with no regard for their humanity.

“They have families,” he says. “They have wives and mothers and sisters and brothers, and ultimately you can’t just say that none of these people matter. If that’s the position that we take, we’re all doomed. The system doesn’t really work for anybody.”

As he speaks, a recorded voice interjects: “You have one minute remaining.”

Asked what he would say to people reading his story for the first time, people full of questions about the charge against him and his claim that he is innocent of them, he pauses.

And then the phone cuts off.

Davidson County District Attorney Glenn Funk declined to comment on the Wilson case for this story, given that it is now working through the court once again. The case has been submitted to the newly created Conviction Review Unit in Funk’s office, where prosecutors are still determining whether to pursue it further.

“Criminal convictions need to be final,” Funk says in a statement to the Scene about the new unit. “Support for victims demands closure and the ability to move on with their lives. However, no victim wants the wrong person convicted for a crime and the real perpetrator to remain free. If new evidence of actual innocence surfaces, this office will take steps to re-investigate a case and move to vacate if we no longer have confidence in the factual correctness of the conviction.”

The Wilson case presents an uneasy balance for the DA’s office. As one team of prosecutors is reviewing whether the case warrants re-investigation as a potential wrongful conviction, another prosecutor is in court hammering away at recanting witnesses. It also highlights the precarious argument that prosecutors make in the face of witnesses claiming they lied to help the state get a conviction. Men dismissed as criminals and liars today were the young boys holding up the state’s case nearly 25 years ago.

At Monday’s hearing, ADA Dan Hamm emphasized the criminal histories of Marquis Harris and Phedrek Davis — Harris’ includes attempted murder, while Davis was convicted of murder in 2003 — and presses them about their apparent admission that they committed perjury at the original trial.

“If I had it my way, I wouldn’t have done it at all,” Harris says during one such exchange.

“Well, you did, though, didn’t you?” Hamm shoots back.

“That’s the game that y’all play,” Harris says.

Later, Pridemore takes the stand and denies he threatened Harris, or any other witness, to secure their testimony. He first spoke to Harris, he says, hours after the murder, when the 13-year-old told him that he knew what had happened and hoped to exchange the information for Crime Stoppers reward money. If that happened, though, it was never brought up at the original trial. And outside the courtroom after the hearing, Wilson’s supporters see it as just another reason Harris might have been motivated to lie about what he did or didn’t see.

Soon, Wilson’s attorney, Jesse Lords, comes out in the hall to debrief the group. Norman’s ruling likely won’t come for 60 to 90 days, and Lords isn’t optimistic about the judge granting Wilson a new trial. But Lords is happy with how Monday’s hearing went. He believes it sets them up well to argue their case in future appeals.

It took just two days to convict him in 1994, but the trials of Cyrus Wilson will not end soon.

Cyrus Wilson mugshots courtesy of Metro Nashville Police Department and Tennessee Department of Correction