There’s a block or so of downtown Nashville that contains three spots critical to understanding Black history in the city.

The best-known — the one Nashville at-large is proudest of, the one we want to talk about — is the Public Square. It was the destination of the silent march that followed the 1960 bombing of civil rights leader Z. Alexander Looby’s home, and where Fisk University student Diane Nash asked Mayor Ben West, who was in the midst of an argument with C.T. Vivian, to use his office to end racial segregation in the city. West replied that he “appealed to all citizens to end discrimination.”

Nash pushed him: Did that include the lunch counters? West said yes, prompting raucous cheers from the marchers — so loud, in fact, few people heard him qualify that by saying the decision was up to the managers of the counters themselves. In the papers, The Tennessean emphasized West saying the counters should be integrated; the more conservative Nashville Banner focused on his quiet qualification.

Dr. Learotha Williams

A few blocks away is a darker place. A place Nashville doesn’t like talking about. The intersection of Fourth and Charlotte (it was Cedar Street at the time) was the center of the city’s slave-trading business. The firms that operated there — and there were many — engaged in the wicked industry that kept white Nashville prosperous and Black Nashville in chains. The firms had pens that could hold hundreds of enslaved people to be callously bought and sold.

Between these two extremes is a gorgeous wedding cake of a building. Built in the mid-1920s with a neoclassical design by renowned architects McKissack & McKissack — the first Black-owned architectural firm in the United States — the Morris Memorial Building was built as the headquarters of the National Baptist Convention’s Sunday School Publishing Board. Other Black-owned businesses occupied its offices as well.

The Morris building — now the only extant building in the downtown core connected with Black enterprise — is a monument of sorts to achievement by Black Nashville on its own terms, particularly in a time when every power structure was aligned against such accomplishments.

For Dr. Learotha Williams, a Tennessee State University history professor focusing on African American history, public history and the Civil War, the Morris building was also his earliest connection to Nashville — through the R.H. Boyd Company, a Christian publisher headquartered there.

“I was born and raised a Baptist in Tallahassee, and we got all of our materials from the Boyd Company,” says Williams. “My father was [Sunday school] superintendent, so it was a rite of passage for us to wait for the books every month and find out what our Sunday school classes would be. Graduating from one class to another was a big deal, and it was cool until we became adults and found out they wanted us to teach the classes. Those books were a big deal. We knew the name Boyd.”

But when Williams took his position at TSU, he developed an even deeper appreciation for the Boyd family — particularly R.H. and his son Henry Allen — after visiting the Morris building. He calls the building “a magnificent shrine,” and describes standing on its roof as making him feel “like Leonardo DiCaprio in Titanic.”

“I get here and find out [Henry Allen Boyd] was president of the Nashville Globe, and find out he was instrumental in bringing TSU to Nashville, and then the connection with the Morris building,” says Williams. “They did more than print Sunday school books. They printed hymnals and songbooks. I saw this man and his family providing a way to physically touch these songs our ancestors raised when they were enslaved. The songs became flesh.”

Boyd house

The Boyds were truly renaissance men, involved in nearly every part of Black life in Nashville in the early 20th century — from the publishing concern to TSU to the One-Cent Savings and Trust Company Bank (now Citizens Bank, the oldest minority-owned bank in the country). When Tennessee segregated Nashville’s streetcars in 1905, R.H. Boyd helped organize a boycott, and along with James Napier and Preston Taylor, he started a bus company. The electricity for the vehicles was provided by a generator in the basement of the National Baptist Convention publishing house, so as to avoid having to buy power from a white-owned utility.

Nashville, though, has done little to honor the family.

“I looked around and saw how Nashville was commemorating the influence this guy had,” says Williams. “TSU has a dorm named for him, and it’s a dorm that needs a lot of work.”

Henry Allen Boyd had McKissack & McKissack build a home at 1601 Meharry Blvd. for him and his wife Georgia in the 1930s. Georgia was also a central figure in Nashville’s Black history as part of the influential Colored Women’s Club Movement, which fought for both racial and gender equality. Now the home on the Fisk campus, once the scene of salons and parties, is crumbling.

“The Boyd house was something that resonated with me because of the disrepair it was in. … This is the capital city, which means the infrastructure for preservation is here, but that house is on its last legs. It’s one of the few remaining homes from that period that still stands [in the area].”

Through his work with preservation nonprofit Historic Nashville Inc., Williams learned that Fisk pulled a demolition permit for the home — and he roared into action.

“It troubled me,” says Williams. “I heard about it after the fact. Had it not been for me being on the board of Historic Nashville, I would have never known. I’m grateful I received word that Saturday that demolition was imminent and that the trucks would be there on Monday.”

With the alacrity of a man on a mission, Williams posted a petition on MoveOn.org to save the home. It garnered nearly 4,000 signatures.

“I put that petition out, and it accomplished what it was supposed to accomplish, which was to get everyone to pull up a second,” he says. “You have a guy that did so much in this city that we fail to acknowledge, that we fail to commemorate, and it gets to the point that even the lasting monuments to his work and his life are threatened by the bulldozer and the wrecking ball.”

While the Boyd home has been saved — for now — the whole fiasco raises troubling questions about why Nashville hasn’t and isn’t doing more to preserve its Black history.

“As a historian, I teach history, and I try to look into the margins and see what other people don’t see or tell,” Williams says. “Oftentimes I wonder if it was this city’s desire to compete with large Southern cities that caused them not to pay close attention to the built environment that was worthwhile.”

As Nashville and the nation wrestle with telling a fuller and more honest history, Williams wants to ensure that includes preserving places that are tangible reminders of the past — just as his North Nashville Heritage Project, an ongoing undertaking collecting first-person accounts of the neighborhood’s history, is preserving memories.

“I try to raise awareness with students because that’s who I interact with,” he says. “These places, these spaces have meaning and value, and I say something that’s maybe a little corny: Every brick, every board, every mortar has meaning, because more often than not, Black brickmakers, Black carpenters put that together. They said, ‘We built this house for the Boyds, and it’s going to be nice.’ That’s the emotional connection they had. The house is a memorial of sorts.”

There are other places that need protection too, Williams says.

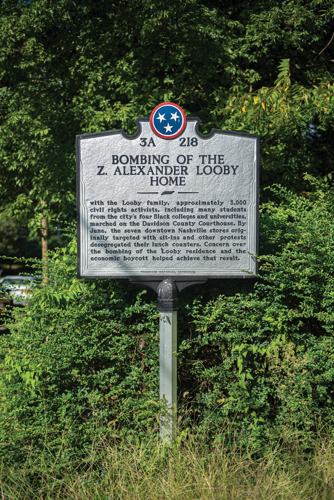

One such place is Z. Alexander Looby’s home at 2012 Meharry Blvd. The home “should be a historical landmark,” Williams says, because its bombing led directly to the silent march culminating in Nash’s famous colloquy with West.

Another is Elliott Hall, which for decades was the site of TSU’s cafeteria.

“When the leaders [of the Nashville movement] from American Baptist College needed foot soldiers for the movement, they knew they could get several at Elliott Hall,” says Williams. “If you look at the articles from The Tennessean on the days following the sit-ins, they were posting students’ names and addresses. Seventy-nine students were arrested, and 50 were from TSU — and I can almost guarantee they were recruited in Elliott.”

Though once slated for demolition, Elliott was saved because it’s one of the few places on TSU’s campus where the art department can store its supplies. Sometimes practical matters do more for preservation than historical or sentimental reasons.

Even a place as seemingly prosaic as Haddox Pharmacy on Charlotte Avenue, torn down to make way for a hotel, had meaning to the Black community. Its location meant residents of the Henry Hale Home had a convenient place to get medication without having to make their way to Jefferson Street.

And this is just the recent history. When Interstate 40 came through the city in the late 1960s, entire blocks of Jefferson Street fell victim to Eisenhower’s progress. Founded in 1918 at 14th and Jefferson, Jefferson Street Church of Christ moved to 26th and Jefferson — its second building featured incredible brickwork, crafted by members of the congregation itself. It was torn down to make way for I-40. As a result, the congregation moved to Schrader Lane in 1967, and became the Schrader Lane Church of Christ.

Jefferson Street Overpass

Williams says it’s unclear if the required review of historic properties — it’s called a Section 106 review — was even undertaken on Jefferson Street.

“In retrospect, there weren’t a whole lot of Black faces at the table,” he says. “It’s probably the same way now.”

The interstate routing destroyed churches and nightclubs, and essentially split the vibrant neighborhood in two. Who knows what other potentially historically important places were traded for an unsightly overpass?

“Our older churches, the churches that were created either shortly after the Civil War or in the early days of Jim Crow, these institutions are monuments to the struggle for Black equality, for freedom in Nashville,” Williams says.

As a practical matter, preserving historical sites isn’t easy no matter their location or whose history is involved. Williams’ first job out of graduate school was working in historical preservation for the state of Florida, and he says in that game, “You catch a lot more Ls than Ws, and even the wins are transient” — something a lifelong love of the Miami Dolphins prepared him for. But preserving history in historically marginalized communities is even harder.

“Oftentimes our spaces are not valued by the larger community,” he says. “I don’t know if that’s because they didn’t know about it or didn’t care to know about it, but I know how history has been taught.”

He goes on, referencing the 21-year-old text The African American History of Nashville, Tennessee by Bobby L. Lovett. “The history of Black Nashville wasn’t written until 1999, and it probably needs updating. There’s a lot of stuff we are still learning. My message to my students and Nashville in general: These old Black schools, these churches, these Black spaces in general, if you ignore them, if you are less than truthful with the history, you aren’t being truthful about yourself.”

Williams says that in Nashville, the historically Black neighborhoods — North Nashville, Edgehill and Edgefield — are close to downtown, making economics a big obstacle as well.

“Money is the driving issue,” he says. “Think about a senior person thinking about leaving behind something for their children. They might be offered $300,000 for a home in College Hill.”

That neighborhood near TSU’s campus is full of “amazing homes,” many built by McKissack & McKissack. “As far as the Black middle class, this spot is as important as any spot in this city.”

In talking about College Hill, Williams takes the opportunity to dispel a lie Nashville tells about itself: that it had a Jim Crow-era Black middle class more robust than its sister cities in the South. Williams says nearly every Southern city tries to convince itself of the same thing.

“You had some African Americans that were really doing it: Preston Taylor, the Boyds and intellectual geniuses. … Flem Otey: I don’t think I’ve encountered any grocer that was doing as well. The undertakers do well. I’m fascinated by Preston Taylor, who parlayed being an undertaker and pastor into being involved in a lot of things. By the same token, you had a bunch of people that were barely getting by.”

He points to Hell’s Half Acre, which was a slum north and west of the Tennessee State Capitol.

“I see it in proximity to all these Black folks doing well,” says Williams. “I don’t know if the shine of their success was blocking out what life was like for most other people, but we had wealth that was surrounded by extreme poverty.”

He says “an old historian’s trick” is to read what newspapers in other cities are saying. In 1926, The Pittsburgh Courier sent George Schuyler to the South. The trenchant Schuyler said he’d never seen a more undemocratic city than the Athens of the South, an acerbic observation that burns through the decades.

Elliott Hall

It’s up to Nashville at-large to recognize the value in places central to Black history, a lesson learned after Fort Negley was threatened. The fort was long esteemed by Black Nashvillians as a place of accomplishment and triumph — and rather incongruously co-opted by the Ku Klux Klan and various Confederate cosplayers — but its importance was lost on much of the city.

Williams says communities that value those spaces must also learn what to do to save them.

“We need to do a better job emphasizing the importance of these spaces. These spaces define a community. They are the heart and soul of our community. Our ancestors built them or worked like hell to get these buildings up. These buildings are symbolic of that. Their influence reaches beyond these communities. These churches teach kids to read and write and stand up to speak, and they go out and do great things in the world. These buildings have meaning. But buildings deteriorate. The federal government created the National Trust, and its purpose is to preserve these spaces that have meaning. If you reach out and say, ‘My building is historic,’ they will assist you. That doesn’t protect it from destruction, but it will provide an avenue to get grants that can help you repair that roof or that plumbing. That listing may bring you under the watchful gaze of someone who has interest in historic preservation.”

Morris Memorial Building

Yes, nominations for the National Register or the National Trust can be daunting, and there’s a misconception that being listed means giving up control of the property. But the labor is worth it, Williams says.

“We need to prepare people to talk about these things in a meaningful way, to explain why this building is important to the community and to Nashville,” he says.

Once those connections are meaningfully made, it’s easier to say no to someone “scratching out a check for your ancestors’ memories.”

“The need to make a buck, to make a profit, never goes away,” he says. “You might hold them at bay for a little while, but these people have a lot of cash and a lot of time, and once they bulldoze it, it’s gone.”

And what’s gone may be more than just a building.

“Much of what I learned about North Nashville came out of J.T. Smith’s barbershop,” says Williams of a longtime Black Nashville institution that is now closed. “Doctors, lawyers, professors and ordinary folks would just come through and just hang out there, and I was struck about how equal it was in that space. There were opinions — some profound, some ignorant. It was a place I could hear about when Tina Turner came to Jefferson Street, or hear about the heavy-handedness of the police.”

Metro is now building a park where the barbershop once stood.

“I remember being in a meeting with [Metro] Parks, and they asked what we could do to replicate that,” he says. “You can build something different, but it won’t be the same. When they tore that down, they tore down a library, an archive.”

It’s up to all of Nashville to fight and work to save places in North Nashville and in the other historically Black neighborhoods, because, as Williams says, our history is our history.

“We need to be shining a bit more light on its role in making Nashville Nashville,” he says of North Nashville. “Its victories were Nashville victories, and where it stumbled is where the city stumbled.”