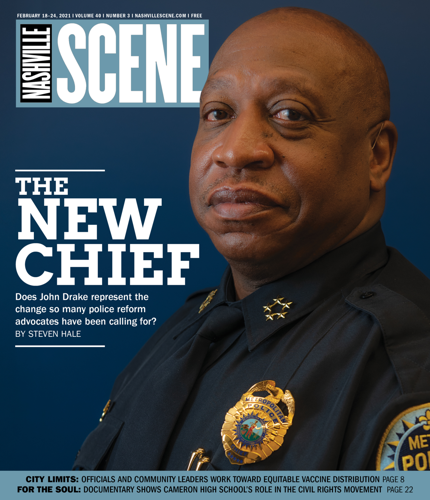

Chief John Drake

When John Drake was announced as the new chief of the Metro Nashville Police Department in November, the news was met in some corners with — at best — skeptical optimism. Activists, community organizations and an increasing number of Metro councilmembers had been agitating for the ouster of longtime MNPD Chief Steve Anderson for several years. Anderson was widely seen as an obstacle to reform, and his tenure had recently included two high-profile fatal shootings of Black men by white police officers. He announced his plan to retire in June amid the historic protests against police brutality and racism in Nashville and around the country, which had intensified calls for change. Shortly after that, allegations of sexual harassment, assault and discrimination inside the department surfaced, raised by women who described a toxic culture inside the MNPD.

The question now: Does John Drake represent the change so many were calling for? He is a Black man and native Nashvillian taking over a police department with a complicated if not broken relationship with some of Nashville’s historically Black neighborhoods and a recent history of overwhelming whiteness in its upper ranks. At the same time, he has spent his entire 30-plus-year career at the MNPD, including the past decade working in the Anderson regime.

Drake’s time as chief so far has been eventful. He has announced several new initiatives inside the department and made a slew of promotions as he reorganizes the MNPD command structure. But he has of course been confronted with more than just internal matters. The Christmas Day bombing on Second Avenue came a little more than a month after Drake was named chief, and he soon faced questions about the department’s handling of an earlier warning about the bomber and his potential for violence.

Drake spoke to the Scene earlier this month about his vision for the department, the challenges it faces and whether he will really be ushering in a new era of policing in Nashville. (Our conversation with Drake took place before the Feb. 10 death of Markquett Martin, a 21-year-old who was shot while being pursued by MNPD officers. Citing surveillance video and ballistic testing, the police department maintains that Martin was killed by a self-inflicted gunshot wound.)

You’ve been on the job around six months, first as interim chief and now officially as the new chief. How would you describe that time period?

I was told there would be like a honeymoon period, I would get to shake hands and kiss babies and all that. But it’s been very little of that and a lot of action. But I enjoy challenges. Some were unforeseen. I didn’t expect some of these. I think overall, the police department [has] risen to the challenge and [provided] services to the community. So I feel good about that, and grateful for the work the men and women have done thus far.

In your press conference after you were named chief, you talked about growing up in East Nashville and spending your whole career as a police officer in Metro. I’m curious — as someone who grew up in the city as a young Black man and has now been a Black police officer for several decades, what was your perspective on the historic protest movement that we saw last summer — in Nashville, but also just around the country?

I grew up in lower East Nashville, and my dad — you know, my family is here several generations — and he endured … riding at the back of the bus, and all those types of things, and sharing his thoughts with me, but he never shared anything that was negative. It was just a period of time that he went through in the civil unrest then with Dr. King and all that and how important that role was. In a way, that’s what I saw in this particular movement, is that people particularly have had enough of seeing incidents around the country, although I feel our police department is good here. It’s alarming to wake up and see on national news an incident such as [George Floyd’s killing in] Minneapolis, and feel heartbroken that you watch someone that wears a uniform similar to yours, kneeling on the neck of a man that looks similar to you without remorse.

So I view the movement, not the riots, as what was needed. But I view the movement as something that was needed to get the attention of law enforcement around the country and to seek the necessary reforms. I feel there are some police departments that don’t have policy and procedure that’s as up to date as ours is, and I think that spurred that movement, to have more agencies have up-to-date policies and procedures and training methods. And we’ve even looked at ours too. We’ve updated ours to be even better than what we were. From a law enforcement executive [perspective], I view it as something that was needed. Something that was long overdue. But I think in the future it is going to help us go a long way.

Obviously you know the circumstances that led to Chief Anderson leaving and you taking over. There are a lot of factors. But there were a lot of people in the community who wanted to see change in the police department, change in leadership, change in some of the policies, change in the direction. You’re a new chief, but you’ve been in the department for more than 30 years. What do you say to people who are skeptical that someone like you can really change the department in the ways they want to see?

We all have our own vision and ways of doing things, and I’ve already made significant changes within the department. I’ve rolled a few people back, promoted a few — all are capable of doing a great job. Created diversity at the highest level here. We now have three African American chiefs that’s part of our staff, we have three women that’s part of our executive staff, we have Caucasians, we have an Iranian. Very diverse executive staff, and that’s resonating through the ranks.

I try to promote, every opportunity I can, any minority or woman within the police department. I’ve looked at moving away from proactive practices and [am] looking at community engagement more and doing precision policing. In the past, we had done a lot of saturating of areas, and hot-spot policing. But now we’re looking at problem people and problem areas. And we’ve had a lot of success, pulling people away in a do-no-harm approach to neighborhoods. So we’re just looking for individuals that have created problems. But then also, another thing is the alternative-policing-strategies concept, something that is new as well. And realizing we can’t arrest our way out of this. We’ve been arresting people for 200-plus years, and some people have 200-plus charges. So we have to look at ways to intervene. How do we identify people, connect them to services and end the path through the criminal justice system? But then, how do we identify juveniles that are at high risk of the pipeline to prison, and how do we connect them to services? So that’s a major move for our police department.

As you were taking over as chief, there were numerous allegations of sexual harassment and even assault and discrimination coming from women from within the department, and they described a toxic culture within the department. You’ve been in the department for many years. Did you see that kind of culture? When you heard those allegations — have you seen the kind of things they were describing?

No, I didn’t see those types of things. In fact, I talked to one of our female deputy chiefs, and she said the same thing. She never saw it, and she even said no one even asked her about that kind of stuff. Didn’t see it, didn’t hear about it until some of the officers had left. But even after they had left, I wanted to address it. I talked to [Deputy Chief Kay Lokey]. She began meeting with all the female officers talking about their value to the department, their value as women and then procedures moving forward — how we’ve established a hotline through our HR division where they can call any type of complaint in, and also they can call directly to the chief of police, they can call me, without fear of retaliation, and know that I would have zero tolerance for anything like that. And then we also have an independent investigation going on with the TBI — they should be concluding their investigation soon and providing their findings. I’ve extended that to the [Community Oversight Board] and the Human Relations Commission. So we want to be transparent, give as many resources as possible to investigate a type of allegation, and then we’ll hold everyone accountable for it.

Another event that happened right after you took over, of course, was the Christmas morning bombing. I know that’s being reviewed. Based on what you know, right now, is there anything you believe the police department could have done differently or should have done differently, either beforehand, or in response to the bombing?

Based on what I know right now, there’s nothing more that we could’ve done. We answered a call of a person that was suicidal [at the bomber’s house in 2019]. We removed two guns that were on the porch. There was talk of someone building bombs. Officers could have just made a report and said, “Hey, this lady is suicidal.” But they didn’t, they went above and beyond. They went and knocked on the door. We had sergeants that actually went to the scene. We had our Hazardous Device Unit officers go to the scene and follow up for days, talk to the neighbors. Sent it to the Specialized Investigation Division, sent it to the FBI. And so we have the after-action review committee going on. I’d like to thank [former United States Attorney] Ed Yarbrough and everyone else that came in to be a part of that. But I look forward to their findings to see if there’s any gaps that they identify.

Do you feel like you have any more clarity or insight as to what the motive was here?

You know, that’s been the talk everywhere. I finally had the chance to take a couple of days off, and I went down to Jacksonville last week and played golf, played with some guys down in Ponte Vedra Beach. They asked the same thing — what was the motive? Right now, the FBI should be giving their final conclusion to me within the week or so. I look forward to that. It’s really bizarre. The beliefs this person may have had, may have had some kind of mental disability, had some issues going there. So I look forward to what the FBI comes up with.

One thing you mentioned at your press conference with the mayor recently is the homicide clearance rate last year falling to 46 percent. I know you’ve already made some changes in response to that, like going back to a centralized homicide unit, but what are some of the reasons you think the clearance rate was that low?

Well, I believe one of the reasons — the main reason — was we had decentralized our homicide unit when it had a clearance rate of about 86 or 87 percent. When it was decentralized, detectives were sent to all of the precincts, and so investigations got diluted just a little bit. They didn’t have the manpower to follow up sufficiently the way that investigation calls for. For instance, you may have a detective assigned to a precinct that will get a homicide and then they’d be assigned a burglary, and that burglary would have hot leads. So you want to get that person off the street as well, so that pulls away from your homicide investigation. With a centralized unit, they’re all in one area, they can discuss what they have going on, they can respond in teams. At precincts, you may have one or two people respond, you may have some other detectives that may help or may not. But with the homicide unit you’ll have teams of six, sometimes 12, you have the TITANS [The Investigative Team Addressing Neighborhood Shootings], comprised of gang detectives and Juvenile Crime Task Force officers, to go back in the neighborhood and recanvass areas, making contact with any witnesses.

Whenever a homicide — or any crime — occurs, it’s like putting a puzzle together. All the pieces are right there at the time of the incident — the victim, the suspect, the evidence, witnesses, everything is there. And then over time it goes cold. So if we can get as much information as quickly as possible, then I think we can be more effective. So that’s a theory, and so far, it’s paying off with the team.

You alluded to this earlier — that we can’t arrest our way out of some of the problems we have as a city and as a society. Do you think that we arrest, or we ask our police officers to arrest, too many people for too many things? Are we kind of sending our officers out to handle situations that would be better off handled by other entities if we could create them?

You know, I feel like we respond to what we should and we make the arrests that we need to. The whole theme of this is just trying to connect people to more services. It seems like when things occur with the police department, if they take the lead, then we have more accessibility with people, we have more people involved to help us with what we have going on. I don’t feel like we over-respond. Look at crisis intervention. I looked at [whether] we should be a part of that with the Mental Health Cooperative, and they agreed to provide some of their personnel as well as some of our officers in plainclothes, not to escalate the situation. I am looking at some calls, where it’s just a report — there’s no suspect information — people just need a report to be able to do that in an automated sense, and not have an officer respond, which would put officers on the street more to provide more services to the community.

When it comes to responding to mental health crises, why do armed officers need to be part of the first responders to situations like that? Obviously, some of these cases become violent, and in some cases they escalate. But as a sort of general rule, why do you think officers have to be part of that first response to situations like that?

Well, you know, we’ve been talking to the Mental Health Cooperative, and they’re the experts. They don’t feel comfortable going on these types of calls by themselves without significant backup. And so if we can team up a couple of plainclothes detectives, just in case a situation goes awry, then we have the capability to try to mitigate any type of threat. Look at the FBI [recently] responding to a call in Florida, and somebody’s watching them on a Ring camera and then just gunning them down through the door. I think it would be beneficial to just partner them together. They feel it will be the best approach as well. And I think that they have better results. It will make them feel better about their job responding to unknown situations, which is what a lot of officers’ fear sometimes is. We don’t know what we’re getting into, whether it’s a domestic violence call or whether it’s a crisis intervention, what you’re gonna be met with.

District Attorney Glenn Funk said last year that his office was going to stop prosecuting people for simple possession of marijuana, half an ounce or less. I’m wondering how you feel about that policy and if that’s something you’re supportive of going forward.

I can’t control what the district attorney chooses to prosecute or not, but state law still has it on the book as an illegal substance. So we still move forward with prosecution of that, and if they drop it, that’s fine. But as we look at some of the homicides that we’ve had, they’ve involved marijuana. And so people that are selling marijuana, getting targeted by some of these criminals, being robbed of drugs and money, and you can just smell the odor of marijuana in their residences. I don’t think we can just overlook this. We have to continue pursuing it on all levels. … The small crime sometimes leads to bigger crimes, and I think that’s what we’re seeing.

[Drake followed up on the issue later, toward the end of the interview, strongly implying that officers have and will continue to use discretion when it comes to people who possess small amounts: “It’s still a violation of state law, and so we prosecute for that. But I’m pretty sure if an officer has come across someone that has a marijuana cigarette or whatever, they may have given him a break. This may have happened, I’m not sure.”]

One new initiative you talked about recently is the Community Field Intelligence Teams. My understanding is that those are kind of replacing these Crime Suppression Units. Can you elaborate a little more on the difference between those two approaches?

Yeah, absolutely. The Crime Suppression Units were units that were just designed to suppress crime, whether it’s street-level narcotics, doing buy-bust situations, going in and doing some search warrants, going in areas and proactively trying to suppress crime, as opposed to the CFIT going in and identifying potential individuals, doing intelligence. Saying, “This person is committing robberies.” We had an incident like that this week — identified a female that made several robberies throughout several different precincts. Identified that person, convened an investigation, was able to make an arrest, go to the residence, get a search warrant, recover the money from the robberies, recover the clothes used in the robberies. They’ve also done that for homicide suspects — been able to identify and surveil and make arrests, without incident. And that’s a good, no-harm approach, as we’re not going into wholesale neighborhoods and dealing with everybody, but the targeted problem people in problem areas. That’s a big difference.

When you say “no harm,” can you explain a little bit more what that means to you?

When I say “no harm,” it’s not going in and just saturating the neighborhood and trying to find one individual by pulling over everyone and doing Terry stops [i.e., stopping someone based on reasonable suspicion] on everyone, having the warrior mindset and just leaving the neighborhood. Actually identifying the person, targeting that person and removing that person without involving the entire community. … Sometimes you do these things and the community feels like they’re targeted, they feel like they’re overpoliced. By having this type of approach, we can go after the individual and remove them.

You’re familiar with some of the tension that has existed between the Community Oversight Board and the police department since its creation. As a new police chief, how do you want to approach the Community Oversight Board, and what is your relationship going to look like with them in terms of making sure that’s a real robust oversight operation?

In my opinion, I feel the Community Oversight Board provides trust from the community and also legitimacy to the agency. There are over 130,000 people that voted for the Community Oversight Board, and for us to do anything other than have total cooperation with them would really go against the voters who are the citizens of Nashville. So from the minute I sat in the chief-of-police seat, I started working on the [memorandum of understanding] with the COB, having a relationship with the director, being able to pick up the phone, call or text. And that’s what we want moving forward. With that MOU agreement, they have the ability to investigate officers, investigate misconduct, and have oversight on some of our policies and procedures. And so as we move forward as a police department, I think the community feels better knowing that there’s an outside arm that can look at us and that they can go to and feel like they have trust when they report misconduct.