Joel Ebert and Erik Schelzig covered their fair share of Tennessee political scandals side by side in the halls of the state Capitol. The two were competitors, Ebert reporting for The Tennessean and Schelzig for the Associated Press and now The Tennessee Journal. Ebert has since moved on to Illinois, where he works for the University of Chicago’s Institute of Politics, but the two veteran reporters teamed up to author Welcome to Capitol Hill, a collection of stories about the political dramas that have always unfolded in Tennessee. The book, out Aug. 15 via Vanderbilt University Press, compiles archival research, new interviews and files pried free from the feds, who might as well lease office space at the Capitol. The authors want the book to serve as a guide for anyone getting involved in Tennessee politics — on what not to do.

Schelzig says he and Ebert were inspired by stories they both wrote looking back at some of recent Tennessee history’s most famous political scandals. Writing a decade later about the 2005 Tennessee Waltz bribery sting, Schelzig says he could already see that some of the guardrails established in its wake had fallen by the wayside.

“A lot of the reforms that had been put in place had pretty much been dialed back over the next 10 years, just in time for the next round of scandals to start cropping up,” he says. “That is what we found throughout. Every scandal is followed by a reaction. People dedicate themselves to more ethical living, and then they get tired of it pretty quickly, and attitudes get more lax, and people get popped.”

Read an excerpt from the book here. —STEPHEN ELLIOTT

Joel Ebert (left) and Erik Schelzig

Ed Gillock was in trouble with the law. The Democratic state senator from Memphis had been indicted in 1976 on federal charges for accepting a bribe “under the color of official right” and engaging in racketeering. The lawmaker was accused of using his position in the General Assembly to prevent the extradition of a man facing charges in Illinois and taking payments to introduce legislation on behalf of four others looking to obtain master electricians’ licenses.

Gillock, himself a criminal defense attorney, recognized the gravity of the situation and soon began soliciting contributions from lobbyists for his legal defense fund. He hired prominent Nashville attorney James F. Neal, a former Watergate prosecutor who would go on to successfully defend Ford Motor Company against reckless homicide charges over deaths in its subcompact Pinto car.

Neal argued the “speech and debate” clause of the U.S. Constitution, which protects members of Congress from being sued over anything they say in the course of their legislative activities, extended to Tennessee lawmakers. Therefore, Neal argued, none of Gillock’s statements or actions as a member of the Tennessee General Assembly should be admitted as evidence in the case.

To the horror of federal prosecutors, U.S. District Judge Bailey Brown agreed.

“To the extent that venal legislators might go unconvicted because of the government’s being barred from proving legislative acts and motives, this is the price that the Founding Fathers believed we should pay for legislative independence,” Brown wrote.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Larry Parrish said the judge had “created a monster” by finding evidence couldn’t be presented to the jury about lawmakers’ misdeeds.

“This now makes black bag legislation legal,” Parrish lamented.

The case worked its way through the appeals process, with the Sixth Circuit agreeing that lawmakers’ activities were privileged. But conflicting rulings in other circuits led the matter to be taken up by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ultimately found in a 7–2 decision in 1980 that state lawmakers cannot claim immunity from federal prosecution for actions conducted while in office.

“We believe that recognition of an evidentiary privilege for state legislators for their legislative acts would impair the legitimate interest of the Federal Government in enforcing its criminal statutes with only speculative benefit to the state legislative process,” Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote for the majority.

The decision removed any doubt of the authority of federal law enforcement officials to prosecute state-level public corruption. Without it, many subsequent probes into illicit activity by state lawmakers in Tennessee and around the nation may have become more difficult — or even impossible.

Even as things stand, public officials have many advantages when it comes to fending off probes into alleged misdeeds. Lawmakers often circle the wagons around their colleagues, no matter how ugly — or believable — the allegations. State law enforcement officials tend to be tepid in their pursuit of public corruption probes, knowing they depend on the government for large portions of their funding. And recent U.S. Supreme Court rulings have again chipped away at which “honest services” crimes can be prosecuted in federal court.

Every state in America has its own roster of elected officials gone bad. Though some are worse than others, no matter how many bad actors or lengthy the list of misdeeds, there’s one through line: the undeniable authority that comes with entering the hallowed and historic halls of the state Capitol.

Republican, Democrat, or independent, the stature that goes with joining the loyal club of public officials who call the Capitol their workplace has a way of attracting both those seeking to do right by their fellow citizens and those who try to exploit the system for their own gain.

For the latter, the dynamics at play are almost irresistible: power and privilege, politics and influence, temptation and excess, all in the name of governance. For the average person, it’s a delectable cocktail that will never be tasted. But for some of those with keys to the doors of government, it can be all that matters.

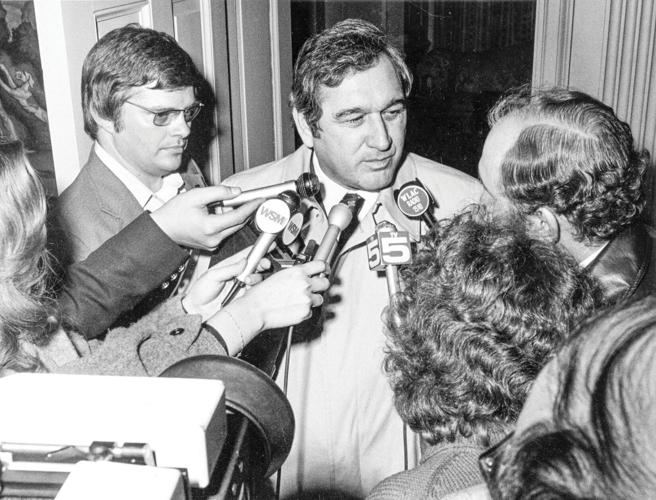

Gov. Ray Blanton, Jan. 15, 1979

From its early days to its modern era, Tennessee has been home to its own infamous miscreants. Our book focuses on the following cases:

- Gov. Ray Blanton’s tumultuous term as governor that ended with his early removal from office amid a pardon-selling investigation.

- A historic collapse of the banking empire of Jake Butcher, a two-time Democratic candidate for governor.

- The Rocky Top investigation into wide-ranging official corruption related to illegal bingo gambling.

- State Sen. John Ford’s career of flouting ethical norms culminating in the FBI’s Tennessee Waltz bribery sting.

- Serial sexual harassment allegations that led to the ouster of Rep. Jeremy Durham.

- The rise and fall of House Speaker Glen Casada, the first leader of the chamber to be pushed out early in 126 years.

- Campaign finance charges against Casada, former state Republican Party Chair Robin Smith, and onetime top legislative aide Cade Cothren — and a separate case against Sen. Brian Kelsey.

While they weren’t the first to face public fervor, federal charges, or falls from grace, history instructs they won’t be the last. Tales of corruption by government officials in Tennessee are as old as the state itself.

Speaker Glen Casada and aide Cade Cothren

In 1797 — one year after statehood was granted — U.S. Sen. William Blount, a founding father of the country, faced allegations of leading a plot to help the British seize land west of the Mississippi River that the senator owned. When the plan was discovered, Blount became the first federal government official to be subject to the impeachment and expulsion process in the U.S. Senate. Despite a severe national backlash, Blount was warmly welcomed when he returned to Tennessee. He later became speaker of the state Senate.

Records detail a host of other tales of corruption or questionable activities by Tennessee’s elected officials.

“It was common talk about Nashville that lobbyists were trading upon the votes of their friends, and that members of the two houses, and employees, were guilty of accepting bribes on various occasions,” the Journal and Tribune of Knoxville reported in 1887. The newspaper outlined a host of bills that were approved with bribes, including measures related to taxing sleeping cars and another to defeat a proposed amendment to the Tennessee Constitution.

In 1895, both Democrats and Republicans in the legislature alleged that bribes had been offered to lawmakers in connection with the gubernatorial election between Peter Turney and Henry Clay Evans the year before.

When the election results were contested, the legislature was tasked with deciding the outcome of the race, and Turney, who was the incumbent Democratic governor, was named the victor after thousands of votes for Evans were thrown out by the Democratic-controlled General Assembly.

In 1910, Gov. Malcolm Patterson pardoned Col. Duncan B. Cooper and his son, who had been convicted of the 1908 murder of Tennessean editor Edward Ward Carmack in a shootout on the street outside the state Capitol. Cooper, who was publisher of the Nashville American, was a friend of the governor. Carmack, a prohibitionist who lost to Patterson in the 1908 Democratic primary, had criticized the governor in editorials for supporting the sale and manufacturing of liquor.

One day, Cooper and his son exchanged “heated words” with Carmack when he was walking home, and the confrontation escalated to the point where Carmack was shot three times and killed. Patterson found the Coopers had not been given a fair and impartial trial. Pennsylvania’s Pittsburgh Gazette said Patterson’s action was “high-handed and outrageous,” adding he was “not fitted to be the executive of a great state.” The Richmond Virginian called the pardon “treason to the state.”

In 1911, the Nashville Tennessean published a story on the first day of the legislature’s return to Nashville that said two Republican lawmakers had been offered money the night before in exchange for voting for a candidate for House speaker.

In 1921, state Sen. E.N. Clabo was charged with accepting a $300 bribe — or the equivalent of nearly $4,750 in 2023 — in exchange for his vote on a bill related to taxes. He was later acquitted.

“Almost always when the Tennessee Legislature is in session there are rumors of corrupt practices, and at times there have been evidences of the truth of the rumors,” the Bristol Herald Courier reported days after Clabo was arrested.

During the Great Depression, the collapse of several banks and the related loss of $6.6 million in state deposits (about $125 million in today’s money) nearly led to the impeachment of Gov. Henry Horton. Memphis political boss E.H. Crump — a rival to Horton’s Middle Tennessee backers — personally lobbied senators inside the chamber on the creation of a handpicked committee to launch a formal investigation into the governor’s activities. The Chattanooga News pronounced Crump the “New Czar of Tennessee Politics.”

A gleeful Crump told reporters about his approach to the deal: “First: observe, remember, compare. Second: read, listen, and ask. Third: plan your work and work your plan.”

As the investigation proceeded, Horton appeared headed for an ouster. But several lawmakers who had previously been critical of the governor were offered jobs with the administration, fielded offers to buy their land, or received proposals for contracts to do business with the state. The governor also announced he would move the 105th Aero Squadron back to Nashville after previously basing it in Memphis in what had been widely perceived as a deal with Crump.

With Crump’s hold on the impeachment effort crumbling, Horton went on the offensive in a number of public appearances. He denounced Crump as “a man who struts like a peacock with a cane on his arm and crows like a bantam rooster.” In what was increasingly cast as a Crump versus Horton battle, public opinion turned against the political boss and in favor of the embattled governor. The impeachment effort ultimately fizzled as a coalition of rural Democrats and East Tennessee Republicans turned against the ouster in 1932.

Crump had failed, but he still came out on top in the following year’s election when his chosen candidate, Hill McAlister, was elected governor.

In 1937 Rep. J.B. Ragon Jr. said he was offered insurance business valued at $1,200, or the equivalent of more than $25,000 in 2023, if he voted for a bill related to county government.

A reporter for the Chattanooga Daily Times said in 1946 it was “very clear to me” when a naturopathy bill was considered by the legislature a few years before that “money had been used” to offer lawmakers bribes.

In 1975, Tom Hensley, a powerful liquor lobbyist known as the “Golden Goose,” testified in a legislative committee that he provided free bottles of whiskey to any member of the General Assembly who wanted one. The revelation came as little surprise to insiders, but the brazen confirmation of free booze flowing to lawmakers shocked the public. Hensley’s testimony came after Lt. Gov. John Wilder formed a three-member committee to look into allegations that two state senators had been offered bribes in exchange for voting in favor of a liquor price-fixing law.

During a 1987 debate on a bill that sought to give lawmakers a pay raise, Rep. C.B. Robinson, a Chattanooga Democrat, said he had seen a lot of money pass “under the table” during his time in the legislature.

And then there was Gillock, the senator whose efforts to beat federal bribery charges ended with the U.S. Supreme Court decision establishing that state lawmakers aren’t immune from facing charges for their actions in office.

Sen. Ed Gillock in 1980

Gillock was known for his arrogant attitude while serving in the state House and Senate, often asserting that lawmakers should be given priority when riding Capitol elevators, standing in line in the cafeteria, or parking their cars. He also engaged in a “voter exchange program” with fellow Memphis Democrat Gabe Talarico, an ad hoc redistricting scheme in which predominantly Black voting precincts were moved back and forth between their neighboring districts to ensure neither white incumbent could be defeated by a Black Democratic primary challenger or a Republican general election opponent. A federal court blocked the practice in 1976, finding the moves were made “for no reason based on a rational state policy.”

“No one wins them all,” Gillock’s attorney James Neal said of the Supreme Court decision that allowed the bribery case to resume. “This was just a little round in the Gillock case. The only battle worth winning is the last one.”

The attorney’s words turned out to be prophetic. Gillock’s ensuing trial ended in a hung jury (he was elected to his fourth Senate term while the case was underway) as did a retrial the following year. But that’s when his luck ran out.

While waiting for the cases to go to trial, federal investigators received a tip that Gillock had been given a pickup truck by a Millington businessman. The gift led agents to evidence that executives with Honeywell had engaged Gillock to help land computer contracts worth $2.5 million with the Tennessee Department of Employment Security and $2 million with Shelby County. At his 1982 federal fraud trial, Gillock testified he was working as a consultant for the company, not as a lawmaker. He also showed disdain for federal prosecutors.

“You haven’t convicted me in two other trials, and you’re not going to convict me now,” Gillock sneered from the witness stand.

The jury thought otherwise, finding him guilty of using his elected office to obtain $130,365 in payments (about $400,000 in today’s money) from the company. Gillock was sentenced to seven years in prison. He emerged from incarceration as a minister. Senate Speaker Wilder, who had declined to remove Gillock from the chamber or his committee positions when he was first indicted in 1976, invited the former lawmaker to return to the Senate as chaplain of the day in 2000.

“He’s found the Lord,” Wilder said in introducing his former colleague from the well of the chamber. “I wish I had what he’s got. I don’t have an 800 number. I have to go through an operator.”

Rep. Jeremy Durham

Welcome to Capitol Hill, which borrows its name from a remark attributed to disgraced former lawmaker Jeremy Durham to one of his alleged victims, provides cautionary tales of corruption and wrongdoing in Tennessee. While most of the officials who are the subject of this book were charged with crimes, this by no means suggests that all public officials are dirty or looking for their next grift. Lessons can be learned from each of these characters, including the dangers of acting on temptation, or the risk of letting pure power become a driving force that overrides the initial motivation that led someone to run for public office.

Ours was far from an exhaustive exploration of unscrupulousness. Rather, the book’s examples offer opportunities to make sense of the modern era of government and politics in Tennessee in a different way. Newspapers and history books are replete with partisan politicians’ rehearsed speeches and talking points, and the daily twists and turns of government. Our compendium of corruption contains lesser explored stories about the inner workings of the political system, albeit ones that are equally necessary to understanding the process.

If these scandals hadn’t occurred, much would be different today. The state’s campaign finance and ethics watchdogs exist because of malfeasance. Publicly known wrongdoing has led to many law, policy, and rule changes as well. Perhaps most importantly, without the ire that each official faced, the halls of the Capitol might still be reserved for those with privileged access — a point made readily apparent by this year’s efforts to expel Democratic Reps. Justin Jones, Justin Pearson and Gloria Johnson. But much work remains.

While nothing can ultimately stop a decidedly corrupt or morally bankrupt public official from crossing the line, the consequences for those who become ensnared should make others in elected office think twice before they act.

Erik Schelzig (left) and Joel Ebert