When I open the door of Percy’s Shine Service, Robert “Percy” Person glances over at my feet. He’s bent over the shoes of a customer, his shoulders back. His customer, a regular, sits in the worn red chair closest to the door — one of four stations in Percy’s place. The walls of the shop are crowded with Titans memorabilia, framed certificates and photos of his customers — statesmen and judges, athletes and actors. So many, he says, that he could never remember them all.

That’s because he’s been in business for more than 70 years. Percy — that’s what everyone calls him, so we will too — started shining shoes in the street as a young man, charging a quarter a shine. After a couple months, he rented a space on Jefferson Street and set up his business. “Been going at it ever since. … I’ve had some hard times with it, and I’ve had some good times with it.”

Percy has a medium build, strong and sinewy. He wears a ball cap, tinted glasses and a neat mustache. Watching him deftly slap polish onto his customer’s boots, you can tell he’s good with his hands. A couple dozen horsehair brushes line the shelf, each labeled with the name of a different color. He holds his rag taut and works it quickly back and forth across the surface of a shoe.

He’s been a fixture — some say an institution — in the Arcade for 31 years. The 119-year-old shopping mall currently hosts a handful of longtime business owners like Percy who have been eking out a living for decades.

When I ask how business has been during the pandemic, Percy says: “The only way I know how to answer that question is, ‘What business?’ Ain’t no business. I’ve been in the strain ever since the COVID-19 stuff been here. Men are not dressing. They’re working at home. Men are not having their shoes shined. They’re wearing tennis shoes. I get tired of seeing a man walking down there in a suit and tie and he got on tennis shoes.”

Casual wear took over dress wear even among some of his best customers, he says. And the dress shoes have changed. In the past 10 years, he’s had to learn how to shine shoes all over again. In the past, all four of his chairs were full. His wife and son were shining shoes, plus a couple employees. “That was when shoe shines were shoe shines and men were dressing,” he says.

On his 80th birthday, Percy was honored by the city and state in a surprise celebration. When he walked into his surprise party, the most powerful people in the city held placards of his likeness over their own faces. “He’s blessed all our lives, and it’s only fitting that we honor him this way,” attorney Hal Hardin told The Tennessean that day.

On the wall, he’s hung certificates from the Scene citing his Best of Nashville readers’ poll wins. He’s disappointed we don’t include Best Shoe Shine anymore. “Shoe shine gotta make a living just like everyone else,” he says.

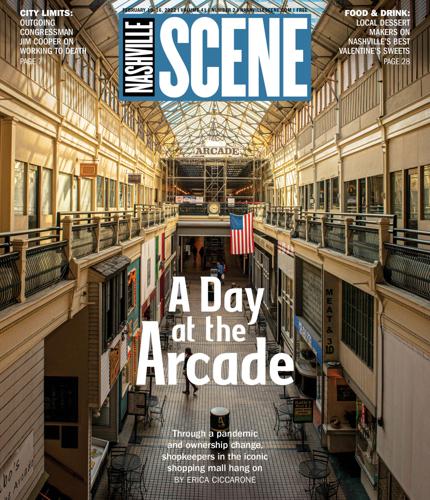

The Arcade extends between Fourth and Fifth avenues downtown — a city block filled with shops on the ground floor and offices and galleries accessible via a balcony above. It opened on May 20, 1903, and by all accounts, the day was auspicious. The railroads reduced their rates, and shoppers and sightseers came from all over to welcome the state’s first shopping mall. The Nashville Tennessean reported that “an immense throng of men and women were in attendance all day long, the latter predominating,” and estimated attendance of 40,000 to 50,000. A band played day and night, and as the Nashville Banner reported, “Hundreds of pretty women in spring dresses and flowery hats [added] to the gaiety of the scene.”

“Palms and flowers, wreaths of roses, boughs of cedar, the pleasing green blending harmoniously with the brighter decorative colors, makes the entire scene a charming one,” wrote the Banner.

The shopping center was the brainchild of a “hustling young real estate agent” named Daniel C. Buntin, who was inspired by the architecture of Milan. He brought home visions of the Italian city’s open-air bazaars, Palladian facades and Art Deco style. Buntin created the Arcade Co. and secured the necessary stock subscription of a quarter-million dollars. Work began in January 1902.

“Too much credit cannot be given to Daniel C. Buntin,” reported the Banner, “the originator and promoter of the scheme, who never faltered from the steadfast purpose of accomplishing what he had undertaken, although there was much opposition at times.”

The opposition was similar to the kind we see today in Nashville. Tenants of property on Cherry and Sumner streets — now Fourth and Fifth avenues — brought Buntin to court. Property owners feared their value would decrease. Infrastructure issues had to be considered, and members of the city council debated the use of public space for private enterprise. Outside one council meeting, the debate grew so intense that one member — a certain Councilmember Craighead — “attempted to strike Mr. Merritt but was prevented by his friends,” reported the Tennessean in 1902. Inside the chamber, the council indulged in a “long and somewhat acrimonious discussion,” but the ordinance passed on its final reading. As for those tenants who opposed the new building, the Tennessean proclaimed: “Some Folks ‘Knock’ Every Enterprise Which Other Public-Spirited Citizens Project.”

Buntin told the Tennessean on opening day: “My plan all along has been to give the small shopkeeper a chance, and I think they have it now and I am sure they appreciate it.” Indeed, myriad businesses opened that day, and many more followed. Visitors could obtain anything from a shave to a piano. The Tennessean advertised pony rigs from Sweeny Carriage Co.; silverware, toys, guns, jewelry and playing cards from Gray & Dudley; “Egyptian curios”; “tasteful hats,” umbrella repair and dressed dolls, to name a few. Upstairs, offices hosted real estate agents, mining companies and much more.

“The smiling faces of the shopkeepers substantiated their statement that their business was already more than they can handle,” the Tennessean reported.

Years later, the Arcade became an important site during the civil rights movement. Among the many lunch counter sit-ins of 1960 were demonstrations at nearby luncheonettes at Cain-Sloan and Woolworth’s. The Tennessean reported that during one such sit-in, white youths were harassing 16-year-old Ralph Jamison, who worked in a barbershop in the Arcade. After enduring taunts and spitballs, the young man dropped a soda bottle down from the balcony — injuring no one — and the mob rushed up the stairs to beat him. When the police arrived, the whites scattered, and Jamison was arrested.

The shops desegregated later that year, and the center continued to thrive. In 1973, the Arcade was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Prepared by Mrs. Donald Drummond of the Junior League of Nashville, the application reads: “It has been said that the Arcade was a small town within a town, complete with its own mayor, where you could buy anything from a twelve cent hamburger to a $5,000 diamond.”

“The Arcade is still flourishing,” Drummond continues, “bringing old world charm to a modern, forward moving city.”

In the Aughts, the Arcade officially became an arts destination, hosting the First Saturday Art Crawl to draw patrons to its galleries one evening per month. Art crawls in other parts of town developed later, but the Arcade’s was the first.

Last year, New York City-based firm Linfield Capital and a local group of investors paid $28 million for the building. The group includes another hustling real estate agent, Rob Lowe, who acts as managing director of the local office of commercial real estate company Stream. In December, the Metro Development and Housing Agency Design Review Committee approved exterior upgrades to the building.

The fate of the shopkeepers is uncertain. “I don’t have the slightest idea of what it’s gonna be,” Percy tells the Scene. “I just hope I still be here.”

Today, many shops and offices sit empty. A maze of scaffolding is set up on the Fourth Avenue side, and few pedestrians can be found on a recent cold Wednesday morning. A young woman wearing big headphones bounces out of the post office smiling, and a few folks walk through or linger. It’s dreary, and the glass roof does not provide the abundant sunlight described in the newspapers of the Arcade’s opening day more than a century ago. But shopkeepers have nevertheless already begun their routine. The beloved Peanut Shop is closed temporarily. A sign reads, “ON MY HONEYMOON.”

Tony’s Shoe Service displays the business’s former name: Tony’s Orthopedic Shoes & Service. But owner Samuel Yi does not limit his business to medically beneficial footwear. When the Scene visits, he is resoling a cowboy boot. The shop is cluttered with shoes — a wall of used footwear that’s for sale, bags of shoes and shiny, resoled boots ready for pickup on the counter. By the window is a large Singer sewing machine — an old but reliable workhorse with no plastic parts, threaded for use.

Born in South Korea, Yi immigrated in 1990. He trained in the same shop with a man named Tony. His last name? “Just Tony,” Yi says. After six years, Yi bought the shop from Tony, and he now runs it with his wife Anna. He handles a recently repaired cowboy boot with care, flipping it over to show me its flawless leather sole. Business has suffered since the pandemic started — he estimates it’s down by 60 to 80 percent. Like other shop owners in the Arcade, he relies on people who work downtown. COVID-19 sent them home.

You can find Semra Triplett in the window of Alterations by Semra, leaning over her sewing machine, a television playing The Price Is Right behind her. She learned to sew from her mother in Istanbul, and after she immigrated to the U.S., she made neckties for her husband. The very first necktie she made for him is framed in her shop. About 28 years ago, Triplett was bartending at the Hermitage Hotel and brought some of her ties in. She put her briefcase on the cigarette machine and sold five a night at $25 apiece. “Everybody went crazy,” she says. Soon she rented out a shop, Semra’s Originals, in the Arcade.

Triplett left the necktie business to care for her twin grandchildren, but two years later returned to a new stall. Rent was $400 a month. The owner, Livingfield More, raised it once to $425. She’s been in business in the same shop for 18 years.

Today, Triplett says she has only about 33 percent of her normal business. She’s more eager to talk about her grandchildren, who are now adults. Just as we’re wrapping up, a young woman comes in holding a pair of jeans in need of a hem.

“Hi sweetie,” Triplett says. “What you got there?” She sends the customer back to the changing area, calling after her, “Are you gonna wear those shoes?” She turns to me. “Most of my girls know to bring their shoes with them. She’s new.”

Of the change in ownership and Livingfield More, who died about a year ago, Triplett says: “Mr. More’s the one who picked these people to sell it to, and I’m hoping he said, ‘Leave Semra alone.’ ”

Down the way, Manny Macca prepares for the day, setting up his workspace — full of pizza dough and peppers, mozzarella and mushrooms. He’s framed by the big glass window that’s got the restaurant’s number scripted in yellow and red paint. No area code needed. He tells me to come back after 3 p.m., when the pizzeria closes.

Manny’s House of Pizza has been a fixture in the Arcade since the mid-’80s. On Jan. 20, 1961, a 9-year-old Macca arrived in the U.S. “The day of Kennedy’s inauguration,” he says. He came of age in Bensonhurst, an Italian neighborhood in South Brooklyn, working in a pizzeria.

He moved to Nashville in 1984, aspiring to enter the music business. To make a living, he got a job in the Arcade, and much like Yi trained in the trade of shoe repair, Macca perfected the art of pizza making. After a couple of years, discouraged by the music industry and maybe a bit homesick, he went back to Brooklyn. But it wasn’t long before the pizzeria’s owner called him up. He was selling the business. Would Macca like to buy? He was in.

These days, Macca struggles to find help, so two of his adult kids — John and Alessandra — are working at Manny’s, as is his wife Adele. When I sit down with Adele for a slice, she eagerly awaits a verdict. For a homesick New York transplant like me, the first bite is bracing. The crust is thin and foldable, if that’s your preferred method of eating. This New Yorker prefers to dig in cheese side up. Manny’s tomato sauce tingles on the tongue. The mozzarella is perfectly proportioned. It tastes like home.

The previous day, Adele says, an out-of-towner stopped in for a slice. “He got an anchovy slice,” says Adele. “He went crazy, he comes back, ‘I need another one. I haven’t had this pizza in 20 years.’ And then he leaves and he gets another slice of anchovy. It was funny ’cause I says, ‘Are you from New York?’ Not that many people like anchovies. I know that was a New York thing. … Customers, I tease them, they says, ‘Do you bring the water down?’ I says, ‘Oh yeah, we ship it every day!’ ”

But Manny’s is not just dear to New Yorkers. Nashvillians have been lining up for pizza, pepperoni rolls, meatball subs and more for 34 years. Manny serves judges and legislators, students and tourists. Everyone downtown knows Manny’s. “Customers love my husband,” Adele says.

Soon, Manny brings his lunch over and has a seat. When asked what the Arcade means to the city, he says: “Half of Nashville doesn’t even know it exists —”

Adele interrupts: “All the old-timers do.”

“This was the center of Nashville at one point,” continues Manny. “This was the first idea of the mall.”

“A lot of our friends,” says Adele, “when they were teenagers, this was the hangout place.”

At one point years ago, kids weren’t allowed in the building. “I would tell ’em, just come through the side door,” says Manny. “Don’t worry ’bout it.” These days, high school students from Hume-Fogg come by for lunch.

A couple from Georgia is finishing lunch at the table beside us. “Unbelievable,” the woman raves, “we don’t get this kind of food where we’re from.” Adele and her daughter joke with them about pregnancy. “He kept me pregnant for five years,” Adele says. Then she gestures toward Alessandra. “I was only planning on two, but she was a surprise baby.”

“I wasn’t about to miss out on all this!” Alessandra says, and everyone laughs.

Right when we’re wrapping up, Rob Lowe — the real estate vet at the center of the building’s purchase — comes in to talk to Manny. He tells the Scene that the Arcade will retain its retail and restaurant element, and the ownership group is working out lease renewals on a case-by-case basis. He’s thinking that Manny’s will stay. [As reported by our sister publication the Nashville Post after the Scene story went to press, it looks increasingly likely that only three current tenants could remain in the Arcade: Percy’s, The Peanut Shop and Manny’s. Lowe declined to comment on specific future tenants or to provide a timeline for renovations, but tells the Post, “Our intention is to be good stewards of the historic property.”]

Some businesses haven’t been so lucky to hold on through tough times and changes. A sign outside Maggie’s Cafe reads: “Thank you Nashville for 26 great years. We will miss you.” Manny Cordova, the owner of Latin American Cuisine and Vic’s Brown Butter Hot Dogs, put his savings into his restaurants a month before the sale. He’s heard from the ownership group that his leases won’t be renewed in April.

A pedestrian named Odie, laden with bags, asks me for bus fare. I don’t have any cash on me, so I offer to buy him a meal at Latin American Cuisine. He orders chicken flautas with rice and beans. He says it’s delicious.

It happens seemingly every time there’s a big change to one of Nashville’s historic sites: Residents bemoan the loss of the city’s character. And why would the Arcade be spared? The city rises and contorts around it. Scaffolding set up for Arcade repairs looks no different from the scaffolding anchored around hotels and apartment complexes that tower over our streets.

Standing in the Fifth Avenue archway, a newcomer could easily overlook the building. This stretch of sidewalk looks unassuming. You wouldn’t think that inside this building is a town within a town that’s survived world wars, economic depression, social movements and everything else that’s occurred over the past 119 years.

But if you close your eyes, you can hear the flags flapping gaily in the breeze, see the wreaths of flowers and the Japanese lanterns, sense the throngs of shoppers. You can imagine the Arcade as it once was — a paragon of art and industry that held not only the convenience of a central shopping experience, but the dreams of a city.