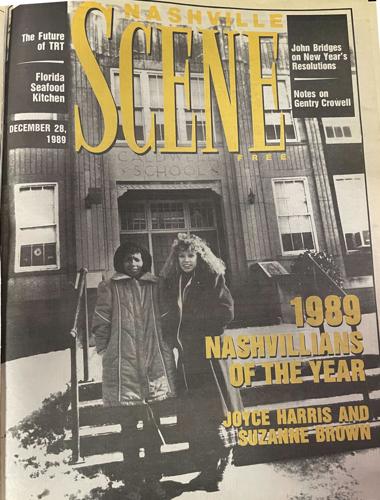

Joyce Harris (left) and Suzanne Brown

The Scene’s 1989 Nashvillians of the Year are Suzanne Brown and Joyce Harris. A committee of community leaders selected these women on the basis of their efforts to end the cycle of deprivation and dependency that has afflicted local housing projects. Importantly, these women believe in the importance of education as a way out.

Brown serves as home-school coordinator for the Caldwell Early Childhood Center, most of whose four- and five-year-old pupils come from Sam Levy Homes (sometimes called Settle Court) in north Nashville. Harris is president of the resident association at Preston Taylor Homes on Clifton Street. In 1989, her work has led to the implementation of a home-school program similar to Caldwell’s at McKissack School. That program fell victim to Metro’s budget cuts this year; Harris is now trying to have it restored.

Suzanne Brown

“We’ll take my car over there,” insists Suzanne Brown. “It’s known.” Just a precaution, as we set out to tour the community she has served for the past three-and-a-half years. Brown is more uneasy about how the people of Sam Levy Homes will be portrayed in print than about any danger that may await us.

It is not, at first glance, an inspiring environment. Some of the breezeways, blocked off with iron bars, look like jail cells. On an icy day, the streets are desolate. In warmer weather, Brown tells me, we would be approached by the dealers. Sometimes deals go bad, or turf is challenged, and there is shooting. Parents often keep their children indoors, out of harm’s way.

It’s easy to call the place a war zone, to recite a litany of misery culled from police reports. By thinking of these people as warriors we may avoid having to think of them as people. It’s a way of blaming the victim, a technique at which Americans are often proficient.

Brown can’t do much to change society’s attitudes. But she is bent on changing ingrained ways of thinking within Sam Levy Homes. “We set out to dispel the myth that low-income parents don’t care about their children’s education and are not capable of helping with it,” she says in a genteel drawl, almost a whisper. “We have proved that idea to be untrue.

“It is a privilege to work in this community. There is strength, there is talent, and all these parents needed and wanted was someone to go out there and make them feel needed and wanted. Everything I do is aimed at making parents feel good about themselves. Then and only then can they help their children develop good self-concepts.

“For every ounce that I give,” she adds, “I get back tenfold. I feel like this award should be divided 250 ways to include all the faculty and staff.”

Every Tuesday and Thursday morning, a few dozen Sam Levy residents gather to discuss the business of raising kids. Meeting in a classroom set aside for them at Caldwell Early Childhood Center, the members of the Parents Club talk about issues affecting their four-year-olds, who are among over 100 enrolled at Caldwell. Brown sets the agenda.

The sessions deal with child growth and development concerns, including language development, discipline and instilling responsibility. She also incorporates topics related to the parents’ needs and interests, such as health concerns and federal programs. And she helps them plan activities.

Since Brown’s arrival, the Parents Club has put on plays, Halloween festivities, easter egg hunts, and the like. Parents help out on field trips, assist in health screenings and help with other administrative affairs at the school. None of these activities will sound unusual to the average parent: Mothers and fathers in middle America assume such responsibilities on a regular basis.

But the Sam Levy Homes are not middle America. Poverty gets in the way of bourgeois values here. Often educationally deprived themselves, the parents of Caldwell kept a distance from the school until Brown came along. Their withdrawal from the learning environment was reflected in the children, who reached kindergarten totally unprepared.

“The kids were dropping out before they ever got started,” Brown recalls. “As they were entering school, they weren’t able to name common household objects. Often they didn’t know their full names; didn’t know colors and shapes. They were a year to two years language-delayed.” Over half either repeated kindergarten or were sent to the Transition 1 remedial program for preschoolers.

Caldwell’s teachers knew that something had to be done for these at-risk students. They began a lobbying campaign, writing to the Metro School Board and state lawmakers. As it happened, this movement coincided with heightened concern among state authorities about parent involvement in schools. “And in 1986, the state and Metro intervened to save the children,” says Brown. Metro now funds most of the program’s $227,000 budget; a state grant covers part of Brown’s salary.

Brown, a West Tennessee native who holds a master’s degree from Peabody, was chosen as home-school coordinator after teaching for 13 years in Metro’s kindergartens and Transition 1. The position was not entirely new to her: getting moms and dads involved has always been one of her jobs. In her previous positions, she often taught parenting classes after school. “I never operated a classroom without parents,” she emphasizes.

The Caldwell program is not unique. In Chicago’s Robert Taylor Homes, the nation’s largest housing project, a comprehensive effort known as the Beethoven Project has aimed to provide healthcare, parenting education, day care and other support services to all families beginning at the prenatal stage. But Brown and the rest of the faculty, unaware of any precedents, built their program from scratch.

The position of home-school coordinator has come to encompass several roles: teacher, advocate, social worker, counselor, friend. “I spend a great deal of time helping parents help themselves, giving them information about resources in the community,” says Brown. “I try to hook parents up with agencies that can help them with their problems.

“Our parents are facing some really tough life struggles. There are a jillion resources in this community that can help. But because their mobility is limited, their access to information is limited. I can get itto them. But there are a lot of communities that don’t have anyone who can be a liaison in this way.”

When I tell Carolyn Doney, a mother of six who is now raising two grandchildren, that I doubt she had much to learn from Brown’s parenting instruction, she disagrees vigorously. The 12-year resident draws a contrast between the schools her children attended and Caldwell. “Those schools where my kids went, they pushed the PTA and the fund-raising,” Doney recalls. “But if a parent wanted to come in and observe a class or take a meal with a child, they frowned on that. I think with the parents being welcomed so freely, that’s what makes such a big difference.”

Doney’s granddaughter Gypsy went through kindergarten before Brown’s arrival; her grandson Michael was in the program’s first class. Doney believes Michael has come out ahead. “I don’t think Gypsy got the advantages and support that Mickey did. She just really doesn’t care about school, doesn’t care about homework, has a problem with her teacher—and Mickey is just the opposite.”

Elmira Shelton sits with her three children in a cramped room, lit only by the television. The window is covered to ward off the bracing cold outside. She seems to be a shy woman, but she greets Brown enthusiastically.

Erica, her youngest, is in kindergarten; Kenneth is in first grade. Both are “graduates” of Caldwell. “It’s meant a whole lot to me and helped my kids out too. It helps them learn a whole lot better. They have better opportunities. And I think it helped me more than it did the kids. I’m over there just about every day.”

“You’re a good person to be around,” she says, hugging Brown.

Most of the residents of Sam Levy’s 480 units who don’t know Brown have at least heard of her. One day a drug dealer was so persistent that, after trying to ignore him, she finally told him who she was and asked him to leave her alone. He paused for a moment. “I’m really sorry about this,” he said, and walked off.

Exhibiting a newfound confidence, the families of Sam Levy Homes are asserting more control over their affairs. In 1988 and again last January, the Parents Club sent letters inviting Mayor Bill Boner to tour their area and get a firsthand feel for its needs. Asking for an increased police presence, the Parents cited their concern for their children, who are “unable to play even in their own yards because of drug deals, fighting, profanity and gunshots.” Boner has not yet taken the tour.

The Club met with more success when it set out to get a fence installed around the playground that lies between the school and Sam Levy. The letter this time told about the adults who often walked by the school building using abusive language, about the cars that drove across the play area during the school day, about the broken bottles and syringes left lying around. (It didn’t mention the disappearance of playground equipment, which thieves sold off for scrap.)

This campaign worked. A new fence went up a year and a half ago, along with new equipment. That both remain intact today is one of the humble victories of day-to-day life at Sam Levy Homes.

Joyce Harris

In a nation where all people are said to be created equal, Joyce Harris would like to see young people included in the equation.

“We want our children to learn, just like the Belle Meade children,” she says. “I try to build these kids up to let them know: you can be somebody. You’ve got doctors who’ve lived in here, you’ve got lawyers, and nurses—in a housing project. It’s just what you want to make of it.

“I don’t call this poverty. I call it a place where all of us have to live,” says Harris. Her neighbor Patricia Johnson chimes in: “I tell my children: Don’t ever say ‘the projects.’ This is not the projects, baby. This is home.”

On a grassroots level, Harris has been trying to brighten the futures of youths in Preston Taylor Homes throughout her 13-year tenure as head of the residents’ association there. “I deal with a lot of these children,” says the activist. “They respect me.” She has sponsored football and basketball squads, with the slightly subversive goal of raising her players’ ambitions. “I’m trying to get ‘em involved in something,” she says, “plus tell ‘em about their education. They can’t play sports for me unless they make their grades.”

Within Preston Taylor’s sprawling confines live over 1,000 children. “You got parents who have children and then their children have children,” Harris remarks. She knows about the task of bringing up kids in this environment. Harris recounts the exploits of the three sons and one grandson she has raised during her two decades in the community: one served in the Marine Corps, another attended Memphis State.... It’s a set-speech, proudly recited.

Harris has become fluent in the bureaucratic language of good intentions. She serves as a kind of ombudsman, helping Preston Taylor residents get access to the many private, church-based, academic and governmental programs designed to help them break the chain of generational poverty. Like Suzanne Brown, she came to realize that despite such efforts, children in her community were falling through the cracks.

“One day I was looking out here at the kids playing,” she recalls, gesturing at the playing field and basketball court that lie just outside her back door. “And I thought about how many of them were four-year-olds with nothing better to do.” The academic performance of these children made it clear that their time could be better spent.

“Too many of the children was going into kindergarten and they were not ready,” Harris says. “They would have to end up going in T1 [Transition 1]. Before the program was put into place, we had 27 children from Preston Taylor Homes who went in T1. They were not ready,” she emphasizes, shaking her finger.

Studies have confirmed Harris’ instinctive feeling that deprived preschoolers would be at risk for later failures. Not only does such lack of preparation virtually assure a student of dropout status later in school—and often in life—but the presence of just one or two of these children in a classroom can disrupt the entire teaching process, to the detriment of other students.

Harris had read about the Caldwell program and was aware of its success. “I called the Board of Education and asked them for a meeting,” she recalls. “They came out here and I walked them around, and they funded the thing.” A Caldwell teacher was brought in as home-school coordinator, and in September 1988, the first class enrolled in a pre-kindergarten program at McKissack Middle School, located next to Preston Taylor Homes.

Now Harris set out to help her neighbors make the most of the assistance offered to them. “It’s hard to get parents in this area involved in things,” she admits. “Some of these parents can be kinda lax-like. But they got involved in this program. I can think of two or three that I’ve seen walking up there. I said, ‘You mean you’re going to the school?’ and they said, ‘Yes, Ms. Jo, I’m walking up there with them.’ They got involved. And that helped the parents to build their self-esteem—something a lot of them don’t have much of.”

This year, every child who had attended the McKissack program was ready for the first grade. “We had eighty-some kids in that program up there,” says Patricia Johnson, pointing at the school building. “This year, they’re all up where they’re supposed to be.”

Neither the immediate success of the McKissack program nor its soundness as a long-term investment, however, would keep it alive when a $20 million shortfall dictated cuts in Metro’s budget. The city saved $167,000 in salaries by doing away with McKissack’s program. Compounding the damage, the budget-trimmers also took all teacher’s assistants away from Transition 1, which will be called on to provide remedial education for some pupils left out of programs like McKissack’s.

Today, as Harris fights to restore the preschoolers’ program, its visible success is her most cogent selling point. Pat Johnson offers examples of the program’s effect on both her daughter Alisha’s educational progress and her own parenting skills.

Johnson shows me Alisha’s report card from McKissack. It evaluates the girl’s progress in various categories: “Identifies self by name... Shows self-confidence... Relates positively to others... Works and plays well with others... Takes care of personal and school property... Participates in group activities... Tries to solve problems by self... Shows self-control.”

“That self-control’s pretty hard for a four-year-old,” chuckles Johnson. “She had problems during the first two periods with that, but you see how she improved in the next four.”

“Alisha is very bright,” declares the teacher’s comment on the back of the report card. Johnson reads it aloud. “‘She is learning to write her name. She actually learned to read all the other children’s names from their nametags!’—I was amazed when the teacher told me that! ‘She listens well now and cooperates.’”

“She can count seventeen crayons in a basket,” her mother adds. “I know she’s learning. And I know the other children can too. If they can maintain this level when they’re four, imagine what they can learn when they get to first or second grade.”

Johnson hopes Alisha will grow up to become a teacher. “She loves books. She wanted me to leave her one of these to read before I came over here,” says Johnson, holding up four illustrated booklets on parenting that the McKissack program had provided her. Johnson reads off the titles: “‘How to Develop Your Child’s Self-Esteem,’ ‘Help Your Child Read Better,’ ‘How to Manage Your Child for Good Behavior’—I love that one; it helps me with my others.”

From the booklets, Johnson gets tips on raising her other children, aged 16, 13, 12 and 10. “I go over and over these books,” she says, demonstrating her use of them with teeth gritted in mock anger: “Before I whoop this child, let’s see what it says here...” Johnson bursts out in hearty laughter.

Marveling at Alisha’s progress, Johnson observes: “There's stuff in children’s heads you don't believe is in them. But you gotta catch ‘em at an early age.

“You know what they say on TV. It's an awful thing for a mind to go to waste.”

MEMBERS OF THE COMMITTEE THAT SELECTED THE 1989 NASHVILLIANS OF THE YEAR WERE:

JAN BUSHING

State Department of Education

BARBARA CHAZEN

Sovran Bank

RICHARD DINKINS

Attorney

BILL IVEY

Country Music Foundation

MIKE NELSON

Political Science Department at Vanderbilt University

MAC PIRKLE

Tennessee Repertory Theatre

ANN REYNOLDS

Metro Historical Commission

Suzanne Brown and Joyce Harris