There’s a long-told tale among folks in Nashville health care circles. According to the story, as the industry was blossoming in Nashville in the early ’70s, an executive at one of the larger health care companies was asked how much it cost to keep a patient in one of his hospitals.

His response? “Doesn’t matter.”

Some take that to mean the cost shouldn’t matter, as long as the patient is taken care of. Others say it’s a statement about being able to charge whatever you want. While this story can’t be fully confirmed, it says everything about the industry and what we see today in terms of health care: It’s hard to know how much things cost; the prices are all over the place; it’s a complicated industry. But regardless, people vitally need the services.

Value-based health care is the idea that service providers should be paid based on outcomes, not just how much service they provide. And conversations about price transparency in hospitals and value-based health care are ongoing. It’s a debate that’s been happening for at least the past three decades.

Overall, Nashville’s health care industry accounts for $84 billion in annual revenue, according to the Nashville Health Care Council, a local membership organization made up of key players in Middle Tennessee’s health care circles. If you look at the membership’s family tree, it’s packed so densely you could spend days trying to learn all the names and titles on it. There are more than 500,000 people employed globally by the health care industry in Nashville. More than 800 companies — companies that either directly provide health care service or are tangentially related to the industry — make their home in Middle Tennessee.

The boon started when Hospital Corporation of America was founded in 1968. Before HCA — which became publicly traded in 1969 — most hospitals in the United States were either nonprofit or religiously affiliated. After HCA, everything changed. The company, which is trumpeting its 50th anniversary this year, altered the scale at which hospitals operated. Dr. Thomas Frist Sr., Dr. Thomas Frist Jr. and Jack Massey started with one hospital, called Park View Hospital, and did much of their planning and early work out of a small house near the hospital.

Now HCA owns or oversees more than 170 hospitals, plus roughly 100 surgery centers. The company is credited with creating a chain system similar to that of hotels and fast-food restaurants — a model that not-for-profit hospitals eventually took up as well. And HCA continues to pick up more properties — on Aug. 31 they signed an agreement to purchase North Carolina’s Mission Health for $1.5 billion.

HCA

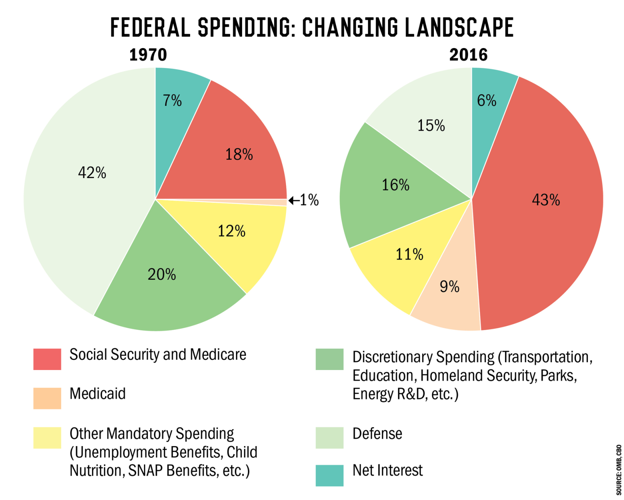

In part, HCA’s success was made possible by President Lyndon B. Johnson’s signing of the Medicare bill, launching a system that gave insurance to people 65 and older, and creating more of a market for hospitals. While Medicare and Medicaid originally started as a way to help those who were extremely vulnerable, the programs have ballooned as the years have gone by. According to statistics from the Congressional Budget Office, spending on Medicaid and Medicare more than doubled between 1970 and 2016. Some of that is due to an aging population, but according to Emily Evans, a health care policy expert and a former member of the Metro Council, the largest issue is that prices are just too high.

“The way HCA used the system is a symptom of a system that is, and has been, the biggest corporate welfare program in the history of mankind,” Evans says.

It’s not that for-profit hospital chains like HCA, Community Health Systems and LifePoint Health — all Nashville-based giants — are totally to blame for rising costs. Some argue that for-profit hospitals, particularly HCA, have brought more accountability into the market for not-for-profit hospitals and government-run institutions, changing the industry for better in terms of care.

The late Dr. Arnold S. Relman was the editor of The New England Journal of Medicine and a critic of for-profit hospitals who pointed out the pitfalls of the system early on. He debated Thomas Frist Jr. in 1985, when HCA was merging with a medical supply company. “Once you say that health care is a commodity like any other, then marketing and advertising and the bottom line — the primary bottom-line needs of the equity investor — will dominate,” Relman said. “Then access of poor to health care, meeting community needs — providing unprofitable services — all take second place.’’

At that debate, Frist admitted he had some discomfort around some portions of commercialized health care and some of the marketing involved. But he also said the company had to “position [itself] to continue to provide the quality health care product,” because the “real world” was competitive.

Thirty years later, we’re still hearing hearing echoes of Relman’s concerns about health care profitability.

What Nashville-based HCA did was “put a stamp on the notion of investor-owned delivery,” says Paul Keckley, a Nashville-based health care policy analyst. “And that’s a permanent imprint.”

Now, Keckley contends, that model is under a great deal of pressure. The health care industry as a whole is in a move-forward mode, trying to figure out what comes next.

“In the past, the sun was the hospital and moon was everything else,” Keckley says. “And that’s just not going to be the case.”

Keckley says that at this point there’s little to gain for the traditional market. Venture capitalists are putting their money into new innovations — $1 billion in venture capital has been spent in Nashville over the past 10 years alone, according to the Nashville Health Care Council — and companies like Amazon are creating their own entities to rethink health care solutions for employees.

“But the systems as they are have been created to protect the incumbents and have actually driven costs up,” Keckley says. “And we’ll watch that merge as the major market levels up. It’s going to get really, really dicey for some folks.”

Largely because of how he challenged the Clinton administration over health care in the ’90s, U.S. Rep. Jim Cooper has become known as someone willing to carefully examine the intricate details of health care policy, even if it’s not politically expedient.

Cooper points to Nashville as an incubator of innovation in health care. There’s HCA, of course, but also St. Thomas, the flagship hospital for not-for-profit hospital chain Ascension, as well as Vanderbilt University Medical Center, which ranks as a top academic medical center. We might have our issues in terms of cost, Cooper says, but at least we have people in our city capable of working on the problem.

“All organizations [for-profit or not-for-profit] try to be efficient, but every type of health system is trying to game the government system,” Cooper says. He notes that while private insurers are still the largest payers in the health care system, government spending on health care has a fundamental problem.

“The federal government doesn’t use real accounting for these programs,” says Cooper. "That’s scary for taxpayers.”

In June, Dr. Melinda Buntin of the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, at a hearing called How to Reduce Health Care Costs: Understanding the Cost of Health Care in America. She relayed that the United States spends $3.3 trillion dollars per year on health care.

“We currently devote 18 percent of our GDP to health care,” said Buntin. “Almost $1 out of every $5 spent in our economy is spent on some form of health care. Many households devote an even greater share to health care.”

Buntin went on to argue that health care infrastructure — which includes millions of employees and thousands of hospitals, medical offices and pharmacies — has created a “health care financing system in which, by and large, providing more services brings in more revenue.”

To counter that incentive to deliver more services, managed care plans started requiring authorization before some medical treatments, Buntin says. “Increasingly, however, insurers are using payment methods and quality measurement to encourage the delivery of high-value care and discourage overutilization of low-value care.” In other words, insurers are trying to make it less likely that patients will receive the kinds of care that insurers think aren’t worth the cost.

But policy expert Evans argues that changing utilization is a slippery slope.

“There is belief among policy people that if you just changed utilization and you didn’t deliver as many services that, ‘Well, by God, we’d save $20 million a year,’ ” Evans says. “[Those critics think] all you have to do is not deliver services so generously, but the real problem is that the prices are just too damn high.”

Brian Haile, who helped make policy decisions for the state on the implementation of the Affordable Care Act as an executive for TennCare, is now the CEO of Neighborhood Health, a community health care organization. He says that while for-profit hospitals do make large sums of money, they often help foot the bill for uninsured people who can’t pay for their health care. Still, Haile sees the future of health care moving toward preventative measures and helping more people take steps like buying healthier food.

“If we can somehow move the needle on things like allowing people to apply for [nutrition-assistance programs like] WIC or SNAP benefits in community health centers,” Haile says, “we can change the way people handle their health by removing barriers.”

Cooper says that when dealing with the health care industry there is a huge amount of prejudice toward preventive care. It’s a gigantic hurdle, he says.

“I had someone tell me once that ‘nobody ever made a profit off preventative care,’ ” Cooper says.

As it has become clear in the years after its passage, the Affordable Care Act turned the health care industry on its head, and finding a replacement that isn’t disruptive isn’t going to be any easier. Buntin tells the Scene there’s no magic solution in health care: Studies have shown that potential cost-containment strategies like transparent pricing aren’t as effective as you would think — people often don’t shop around for the best price when they’re acutely ill. It’s discouraging, Buntin says, because so many think transparent pricing could make a huge difference.

“For all of the concern about health care costs, we do have one of the most advanced health care systems in the world, albeit one that does not serve all citizens equally well,” Buntin says. “We have gleaming hospitals that employ thousands of people in communities across the country, and nearly every day brings stories of medical breakthroughs like immunotherapy. In other words, our costs are also cures, jobs and incomes — and thus stemming their growth is not without challenges and costs of its own.”

Nashville is the right place to try to make change happen in health care, although the varying views and methods seen around the city could make anyone’s head spin. Because the presence of the industry in Nashville is so great, any changes made here are bound to send a ripple through the greater health care market.

Getting any two people to agree on the right solution has proved daunting over the years. But in a city where three men can build up a company from one hospital to more than 170, and change the trajectory of health care delivery systems, surely 500,000 health care industry employees can find an innovative solution to rising costs.