Jessi in her art studio

Jessi Zazu had a choice.

It was April 22, eight days into a 10-day radiation regimen to clear spots that had emerged — bright and blown-out, like photographs of ghosts — on the murky gray MRI picture of her brain. Every day of brain radiation, she rallied the will to sit in a hospital waiting room before undergoing the tedious procedure. She had to decide if that tedium was worth a shot at feeling better. On some days, like April 22, making that decision was tougher.

Patients with Jessi’s prognosis are not obligated to try to beat the disease. Her cancer is rare and aggressive. Doctors, who have sworn an oath to do no harm, cannot guarantee that the physical and mental toll of the treatments they prescribe are worth the cost.

But here’s the thing about Jessi: Never bet against her in a fight. She may be small-boned, with delicate features and an easy smile, but she has already conquered a world of trouble. In many ways, she’s only beginning to know the scope of all that she can do. So when confronted with the option to battle her cancer or not, she says, “There was never any question that I would just let it take over.”

She’s a hardwired survivor. She has emerged from every dark, lonesome corner of this experience to write music, create art, bury a demon or two and find a new depth of love in the people around her. When confronted with the unthinkable, she has moved through the world with a balance of ferocity and grace that feels almost ancient — outside of time. She is 27 years old.

To learn the source of her mettle, it’s important to understand her story. It’s got grit and twists, and it starts outside of Nashville.

Jessi with her mother and brothers Emmett (right) and Oakley

Jessi was born at the Williamson Medical Center in Franklin. Her parents, David and Kathy Wariner, are both talented artists who moved often during Jessi’s childhood. Jessi has two younger brothers, Emmett (now 25) and Oakley (20). Growing up, they lived in small towns across Indiana, Tennessee and Kentucky.

David and Kathy split in 1994 and divorced two years later. For much of Jessi’s childhood, Kathy was the sole provider — at various times, Kathy worked as a welder, an illustrator and a Starbucks barista. She struggled to make ends meet, but they didn’t always.

Kathy tried to show her children beauty. Once in Kentucky, when Jessi was 10 or 11, Kathy pulled her out of bed, took her outside and showed her a night-blooming morning glory vine that had blossomed in the curve of a crescent-shaped piece of driftwood she had nailed to the top of a pole in the yard. It’s one of Jessi’s fondest memories.

Jessi also remembers sticking out among the other kids in small Southern towns. As a high school freshman in Henry County, Ky., she was assigned to write an essay on things that are “the best.” Fifteen-year-old Jessi wrote that communism was “the best” form of government. And though the teacher didn’t give her name when mentioning “one student’s” unique paper, everybody turned to look at Jessi.

She was shy and quiet, but saw the world differently than her peers, and the Henry County school system was less than forgiving. She dropped out after freshman year, did home-schooling for half of her sophomore year, then decided to get her GED. She started dating a boy against the wishes of his mother. Then, when Jessi was 16, her boyfriend ran away from home to stay at her house. The boy’s mother called the police on Kathy and Jessi’s stepfather, who were both arrested for kidnapping. They were later acquitted, but Jessi says it was traumatic.

In jail, separated from her kids, Kathy needed to calm her mind. She found a pencil stub and drew pictures of the other inmates on anything she could find. Word got around that she was an artist, and the women in jail started approaching her, asking if they could sit for portraits. Many hadn’t had their picture made in years. Kathy says several of the inmates cried when she was released.

But all hell kept breaking loose when she got home. Jessi’s stepfather, furious about the arrest, kicked Kathy and the kids out of the house. He moved their belongings to a leaky-roofed shack; almost everything was ruined. When the family went to collect their things, Jessi found a watercolor she had painted when she was 6 years old, washed to nothing by the rain.

Jessi needed to leave, wanting to take control of her life and shape it into something large and wonderful. That summer, she went to Southern Girls Rock Camp in Murfreesboro, where she’d been a regular camper since she was 12. She took a screen-printing class and showed such striking talent that her instructors, who owned and operated Grand Palace Silkscreen in Murfreesboro, offered her an internship if she could ever get to town. She set her mind to figure out a way.

During camp, she learned that one of the directors would be traveling to Costa Rica that summer and was happy to have Jessi house-sit. That gave Jessi at least a month’s worth of rent-free living to figure out her next move. When she told Kathy her plan, Jessi says, “Me and her, we just sat there and cried. I cried my eyes out because I didn’t want to leave Emmett and Oakley. But I had to get out. I knew my life wouldn’t be what I wanted if I stayed.”

Jessi moved to Murfreesboro in September 2007. She printed show posters during the day. At night, she ran lights for the underground shows Grand Palace hosted. She saw Nikki Kvarnes, who she knew through friends at rock camp, at shows too. She and Nikki had clicked almost immediately. They agreed they should meet up and jam.

One night, Kelley Anderson, who founded Southern Girls Rock Camp when she was 18, asked Jessi to run sound for a band called The Trampskirts. At the time, Lauren “LG” Gilbert, now the lead singer for Thelma and the Sleaze, was a guitarist in the band. After the show, Nikki pulled Jessi aside and apologized that they hadn’t gotten together yet, but explained that she’d been dealing with trouble at home. Nikki said her roommate was moving out, and she wasn’t sure how to make rent. On the spot, Jessi offered to move in. On Oct. 1 of that year, she did.

“I woke up every day and sat on the porch and played guitar,” Jessi says. “I was trying to learn to yodel. I was driving everybody nuts. I was exploding. I was so happy to be free of all of the chaos at home. I was surrounded by all these people who played music and loved it as much as I did. I had never been so happy before in my life. I just wanted to be somebody.”

The story from there is fairly well-chronicled, but the short version is that Jessi went from being a kid on the porch to an internationally acclaimed musician. Jessi and Nikki recruited Kelley to form a band they called Those Darlins, writing songs and playing at Murfreesboro holes-in-the-wall. In 2008, they traveled to New York to record their first album, Those Darlins. They drank and shredded and wrote together, raging onstage and breaking the hearts of the men and women in the crowd who fell in love with them. The band grew into themselves, grew their audience and toured. Linwood Regensburg, whom they knew from camp, joined the band as their drummer in 2009. Eventually, he’d move to bass. In 2011, they released Screws Get Loose. The following year, Kelley left the band, recorded a song called “Cactus Blooms” on her own, then settled in Memphis.

Those Darlins’ farewell show, Jan. 29, 2016

In 2013, all the whiskey and road food and poor sleep caught up with Jessi. She didn’t feel very good and began to think the choices she was making in those sticky midnight hours after shows or out at bars weren’t fun anymore. She decided to stop drinking and sought support for that. She holed up in her room for stretches at a time, stripped naked, and drew gesture and contour self-portraits to figure out what she looked like — who she was when she was sober. She wrote songs that ended up on the band’s 2013 album Blur the Line. That August, she put her artwork in a show called Spit at Nashville’s late Ovvio Arte gallery.

Again she changed the course of her story. She started eating well and walking more. She looked around and saw a huge amount of work to be done. She had always felt passionate about social justice, so she joined the Nashville branch of Standing Up for Racial Justice, an advocacy group that works to dismantle white supremacy. She wrote a song about the underrepresentation of women in music. More and more, she wrote music that took on sweeping political issues. She and Nikki started to see the Darlins differently, and after months of wrenching back and forth, the band split up.

Those Darlins left Nashville for their farewell tour in the winter of 2016. It was interrupted by a blizzard, forcing them to return to the Northeast after the tour to make up a handful of shows. In February, before going back to the cities that had been snowed out, Jessi was staying with her boyfriend while looking for a permanent place to live. At about midnight on Feb. 13, he broke up with her, and she moved her belongings out of his house in the rain over Valentine’s Day weekend. At the end of the month, she got in the band’s burgundy van to make up snowed-out shows in Boston, D.C., Philadelphia and New York.

It was about then that she started hemorrhaging blood.

Jessi had known something was off before the bleeding got out of control. In February 2015, she had a normal pap smear. The following October, she made an appointment with her gynecologist to discuss symptoms that worried her. She was bleeding, not much, but wanted to make sure nothing was wrong. Her doctor said that was normal for some people and that she should come back it if got worse. It did, so Jessi scheduled another appointment that same month. He examined her again and told her not to worry. He looked her in the eye and said, “I can’t tell you what exactly this is, but I can rule out pregnancy and cancer.”

She quieted the warning siren that kept going off in her head. Even when during her farewell tour, she found her clothes caked in blood at the end of the night, she thought that maybe the stress of breakups with her band and her boyfriend was causing her body to do strange things.

When the tour wrapped in March 2016, she tried to see a doctor back home in Nashville. The only place that could fit her in was Planned Parenthood. She was shedding so much blood that the clinicians there worried she could have internal bleeding. They said she needed to go to the emergency room. As Jessi cried, waiting for Linwood to pick her up from the Planned Parenthood parking lot, a man, blinded by his own agenda, held up a sign and yelled at her about the sin of abortion.

The ER dismissed Jessi with abnormal bleeding. The next day, one of the gynecologists she’d called had an unexpected schedule opening. Jessi was alone when the doctor first told her she was likely having a heavy period, then, after completing a physical exam, recommended a biopsy.

The results confirmed her fears: At 26, Jessi was diagnosed with cervical cancer.

She later learned that her cancer was caused by a strain of human papillomavirus, or HPV. More than 80 percent of sexually active women and 90 percent of sexually active men have some form of HPV, according to the National Cancer Institute, though the majority of strains are harmless. The harmful ones cause 3 percent of all cancers in American women every year.

Over the past 40 years, the number of deaths per year from cervical cancer has declined by 50 percent. According to the American Cancer Society, the decrease in mortality is due in large part to the higher frequency of pap smears, which started in the ’70s. Pap smears generally enable gynecologists to detect pre-cancerous cells outside of the cervix. But Jessi’s cancer was unusual: It started on the inside of her cervix, which meant it was more difficult to detect. It also meant that by the time the cancer breached her cervix and spread to her vaginal wall, it was too large to remove with a hysterectomy.

Jessi got a second and third opinion before she settled on an oncologist. She began the standard course of care for stage 2 cervical cancer patients, which was low-dose chemotherapy once per week for six weeks, daily radiation of her pelvis for six weeks, and targeted radiation of her cervical tumors, called brachytherapy, for a total of eight weeks of treatment.

The list and timeline of her treatments make this portion of her life sound sterilized or clinical, but the reality was intensely visceral.

Take brachytherapy. At the start of each session, Jessi was wheeled into a beige waiting room while her radiation oncologist and a clinician calculated the radiation field necessary to target Jessi’s tumor. Then they inserted metal rods into her cervix through a plastic tube that had been surgically implanted for the course of her treatment. To keep the rods in place, they packed her vagina full of gauze dipped in iodine. Then they moved Jessi to the radiation room and attached the metal rods in her body to a metal stand connected to the radiation machine. The physicians would exit, close the door and leave Jessi by herself on the gurney, where she could hear her radiation oncologist explaining to a gaggle of medical students her name, age and the stage of her cancer.

“Jessi?” her doctor would ask over an intercom. “You ready?”

On her go, the machine turned on. It whirred and lights blinked as the radiation traveled through the metal inside her. After about eight minutes, her doctor turned off the machine, re-entered the room and began to remove the gauze. Having the gauze inserted and removed became increasingly painful for Jessi, as the radiation agitated and inflamed cells near the treatment area.

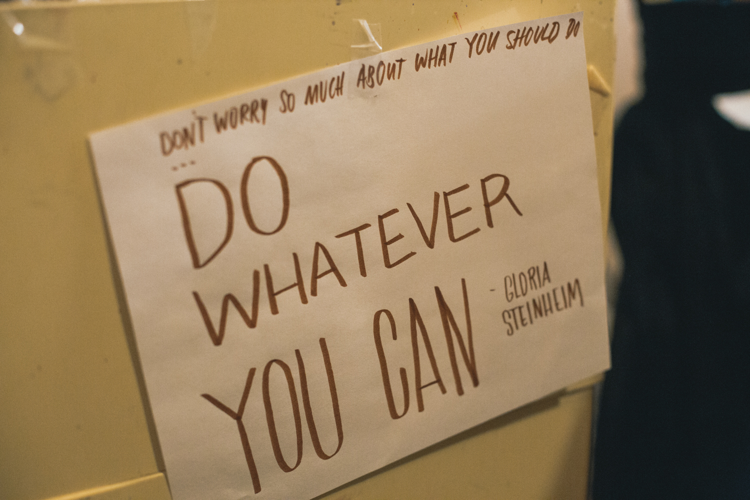

But during the long, surreal hours lying prone in the waiting room, Jessi took her sketchbook and drew everything she could see. She learned every corner of the space — even the art on the walls, which she found unremarkable. When her radiation oncologist learned Jessi was an artist, she commissioned Jessi to paint pieces for the radiation room. Jessi loved the idea. “I was so excited,” she remembers. “I wanted to try to create something that would give people hope. Something strong, but not scary, that would acknowledge what it means to struggle and inspire people to fight.”

After Jessi finished brachytherapy on June 30, 2016, she threw a potluck party to celebrate. She scheduled follow-up scans for three months later, to check whether the therapy succeeded. She was ready to move on.

In late August, Jessi felt a swollen lymph node on her neck. She wanted to be proactive and get a biopsy, which her care team signed off on. But because she’d have to go through the ear, nose and throat department rather than oncology, she got shuffled through the system. Forms were faxed and lost, and faxed again. The scheduling moved glacially.

On Oct. 17, six weeks after Jessi flagged a problem, she finally saw a doctor who biopsied a lymph node in her neck. The results showed it was positive for the same type of cancer cell originally found in her cervix.

The news hit her hard. Jessi returned to the low, nightmarish space where her fears, grown wild with the new information, raced through her brain as she figured out what to do next. She stayed in that headspace as her oncologist listed potential next steps, none of which was a cure. She and her friends researched alternative therapies, overseas treatments. Her cough got worse, leaving her with pain that felt like being knifed in the ribs. She muscled through and recorded music with Linwood — when she could summon the strength to leave the house.

One night, after Jessi had a string of bad days without a turn for the better, Kathy insisted they go to the hospital. Jessi was much worse off than they had thought. She was immediately admitted to the intensive care unit, where she was put on oxygen and given a larger amount of morphine for her pain.

But her eight-day ICU stay jolted Jessi out of the depths. Swallowed in white hospital blankets and hooked up to machines, she got battle-ready. Jessi saw the severity of her own condition and set her intention, yet again, to face it head on. “That was a big realization for all of us,” Jessi says. “It kind of whipped our butts into gear.” She decided to go forward with a second, more aggressive round of chemotherapy. She had her first infusion on Dec. 2, a few days before she was discharged to go home.

Then finally, Jessi caught a break. Slowly, cautiously, she monitored signs that the chemo was controlling her disease. Incrementally, she regained strength. She started going on walks outside again. About a week after chemo, she tried breathing without her oxygen tank. She took the tubes out of her nose for longer stretches of time every day.

Now that she saw the true scope of her fight, she used the gap in action to inventory her armor. Earlier that year, Jessi had been kicked off of Blue Cross Blue Shield mid-treatment when the insurer pulled out of the marketplace established by the Affordable Care Act. Jessi purchased private insurance, but knew the company might push back if she wanted to try treatments outside of the standard of care. She felt better, but she was sure she wasn’t going to be able to work a day job or tour, and she’d need money to live. She talked to her family, she talked to Linwood, and around Christmas 2016, Jessi began building a plan to lay her story bare to the public and ask for help.

She came up with the idea of a campaign called “Ain’t Afraid,” named after a song she wrote for Blur the Line that talks about her earlier metamorphosis, when she put in all those hard hours to change for the better. The song, which she wrote years before she was diagnosed with cancer, mentions finding a tumor on her body but overcoming her fear.

Jessi paints a ceramic plate for her upcoming art show

For the second time in her life, Jessi decided to shave her head. She wanted to get ahead of the hair loss that would come with the new round of chemo. She invited over her friend and fellow Nashville rocker Olivia Scibelli — lead singer and guitarist in Idle Bloom — who is also a hair stylist. Jessi wore a T-shirt she’d made that said “Ain’t Afraid” in red paint. With a small group of friends, Linwood filmed Jessi talking about her cancer diagnoses. Then Olivia shaved off Jessi’s hair. Her friends clapped and whooped and cried. “I feel like I’m going to live,” she says in the video. “And even if I don’t live, then I wasn’t supposed to live. And I want everyone to know that I am a fighter, and I will never give up.”

Jessi’s publicist sent the video and a link to a crowd-funding page to the Scene, Spin, MTV, Rolling Stone, NPR’s All Songs Considered and more. Jessi posted it on Facebook and Instagram. Then she waited.

And as Jessi has a history of doing, she tapped into a genuine outpouring of art and hope and love. Fans who’d watched her play for years mailed her packages full of pictures and notes and gifts. They donated money, and orders for “Ain’t Afraid” shirts matching Jessi’s started pouring in. As of press time, she’s raised more than $50,000.

“I knew there was going to be a response, it was just so much more grand than I thought it was going to be,” Jessi says. “Thousands of people reached out. They pitched in — they told me heartfelt stories. I felt like so many people had my back — like I had an army of people that were with me.”

The collective instinct to help — and the stories people shared with her — changed Jessi’s whole perspective on Those Darlins. “Before I felt defeated, because I had put so much energy into the band, and it was imploding. I didn’t think anybody heard what I had been trying to say all those years. But after the ‘Ain’t Afraid’ video, I realized people had heard me the whole time. They wrote me about how our music impacted their lives in a significant way. I don’t have words to say how much that meant to me.”

Jessi got to work, fueled by a wave of support. She spent hours at a time in her studio, painting pieces for the radiation room. She came up with a concept she believed would convey the right mix of power and hope — creating paintings that reference martial arts combined with the natural world.

She wanted to show the beauty and vulnerability in a struggle. To fight like Jessi, you must be a stone-cold warrior. You must, at the same time, feel everything.

There was still plenty to feel. Before the second round of chemotherapy, Jessi had started seeing flashes of light. During her time in the ICU, doctors gave her a brain MRI that didn’t show anything wrong. But she started to see strange things, like a “black curtain” at the top of her left eye.

She marched through a barrage of appointments and biopsies until her opthamologist recommended emergency surgery to reattach her retina. The night after the procedure, the pain got so bad that her brothers, who had been staying at her house off and on, slept with her on the couch so they could help when she woke up screaming. Her vision is still hazy in that eye, as oil holds the retina in place.

None of it could keep her down. On Feb. 11, Jessi went to She’s a Rebel, a ’60s girl-group tribute show she co-founded three years ago with Adia Victoria’s drummer, Tiffany Minton, and other women musicians in Nashville. She planned to play it by ear and get up and sing if she felt good enough. After several acts, local singer Ariel Bui introduced Jessi Zazu, and the crowd lost their minds. Backstage, she ripped off her headscarf. She stormed out and hit the spotlight like a fury. She had one bloodshot eye and wore a plunging black velvet dress. She sang “Nobody Knows What’s Goin’ On (In My Mind but Me)” by The Chiffons. She radiated strength and grit and love. She shone otherworldly. The crowd threw arms into the air, leaned back and yelled when she was done.

Jessi still chooses, every day, to soldier on — even this spring, when she learned the cancer had broken through the chemo treatment that had worked so well at first. Even when small spots started showing up on her brain scans. The brain radiation gave her searing headaches and made her unable to keep down food, wearing her out so much that seven days into the treatment, she looked within herself for the fuel to complete it, and thought she might be empty.

Jessi’s mother Kathy surrounded by some of her own art

But on April 22, like every other day in the fight for her survival, Jessi had a choice. She carved out a few hours to think it through. She spoke to her radiation oncologist, she talked to her family, she reached out for research help from her friends. In the end, she faced the hospital lobby again. Again she completed the slow march through antiseptic-scented rooms. She did it because she thought it would give her the best shot at the fight.

Besides, she has an art show coming up, featuring the pieces she painted for the countless other patients who will stare, scared and lonely, at those same beige hospital walls. Her art will hang next to a new series by Kathy, because she too has painted her way through this past year. After all, Kathy taught Jessi how to make art to get through this life.

They’ll open their show together June 17 at Julia Martin Gallery. They’re calling it Undefeated, because no matter the odds against her, or the fact that no one could fault her for giving up in the face of them, Jessi seems determined to live her life. She always has.

She’s the master of her own fate. The undefeated Jessi Zazu.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com