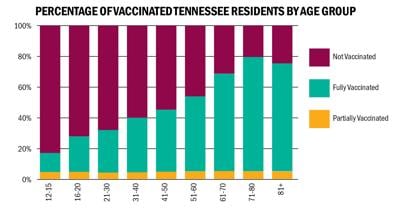

Seven months after the first COVID-19 vaccination in Tennessee, only 42.4 percent of the state’s residents have received at least one dose. Only 38 percent are fully jabbed up, according to the state’s latest data. Tennessee’s vaccination rates are among the lowest in the country.

Tennesseans who are skeptical about the effectiveness of the vaccine can look at the data and see the remarkable impact that even this state’s meager vaccination campaign has had. Cases, hospitalizations and deaths from the virus have all plummeted since the end of 2020. No doubt that’s due in part to the fact that vaccination rates have been highest among older residents who are most vulnerable to serious illness from the virus.

But more recent trends have public health officials warning against complacency. On July 9, the Metro Public Health Department tweeted that “over the past week, our team has observed a 25.7% increase in active cases of COVID-19.” The health department also noted an increase in the test positivity rate and reiterated that the so-called Delta variant of the virus has been identified in Nashville. At the state level, the seven-day average of new cases also began trending upward in the first week of July.

As many pandemic-related restrictions have been relaxed if not lifted altogether, state and local health officials say the best protection against the virus and the variants that have been circulating in recent months is vaccination. But getting Tennesseans to trust that fact and act on it at the scale needed to truly snuff out the virus has proven difficult.

As Sarah Tanksley, communications director for the Tennessee Department of Health, notes, resistance to the vaccine is not unique to Tennessee. Other Southern states have had similarly lagging vaccination rates. The divide is not just regional but political; states won by President Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election have higher vaccination rates than those won by Donald Trump.

In April, the TDOH commissioned a third-party survey of 1,000 adult Tennesseans about their views of the vaccine. Among the survey’s main conclusions, according to the department: “The primary concern is the speed and haste with which the vaccines were tested and developed,” and “white, conservative rural Tennesseans are the least willing to accept the vaccine and seem to have planted their heels in the sand.” The results of that survey, Tanksley says, informed the sort of information the health department has been putting out since.

The public figures who those white, conservative rural Tennesseans are most likely to listen to have not exactly been the most helpful when it comes to cultivating trust in the vaccine. Gov. Bill Lee received the vaccine in March, but did so as quietly as possible. At the state Capitol, the health department found itself under attack when Republican lawmakers threatened to eliminate the department because of outreach efforts they deemed were “peer pressuring” teens into getting vaccinated.

More recently, right-wing figures in the state and on the national stage have been demagoguing about the Biden administration’s efforts to encourage Americans to get vaccinated. Earlier this month, in response to White House announcements about local door-to-door canvassing to provide information about the vaccines, state Rep. Jeremy Faison tweeted: “You’re welcome to the house. We can go sit on my very cool deck and sip some sweet ice tea. We can definitely talk politics. However, you’ll not put a needle in my arm.”

Although Faison said in a subsequent tweet that he does not oppose the vaccine but doesn’t believe the government should “push” it, his comments echoed those increasingly coming from right-wingers with even bigger platforms. U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, continuing a streak of Holocaust references, recently called members of the Biden administration’s vaccination campaign “medical brown shirts,” a reference to Nazi paramilitary groups who aided Adolf Hitler’s rise. Fox News hosts, led by ratings giant Tucker Carlson, have smeared the vaccination information campaign and, like Faison, falsely implied it includes forcible injections.

Meanwhile, the unvaccinated continue to make up almost all deaths and hospitalizations from the illness — and they also serve as a breeding ground for new variants. Tanksley says state health officials will be coordinating with higher-education institutions to hold vaccination events and encouraging local health care providers to become vaccine providers so that Tennesseans can get information and a shot from medical professionals they are more likely to trust.

As this story was going to press, The Tennessean's Brett Kelman broke the news that Dr. Michelle Fiscus, who was heading up the state's vaccination efforts, had been fired. Fiscus told Kelman she was being tossed overboard to appease state Republicans.