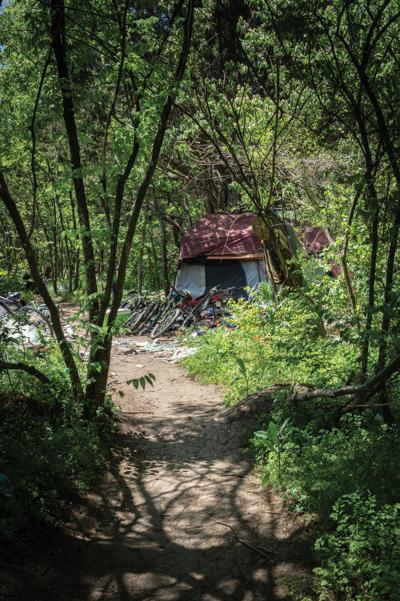

A Madison campsite in 2023

State troopers have arrested at least 10 unhoused people in the past month under a 2022 law prohibiting outdoor camping on public property, according to court records.

The arrests have been concentrated near Riverfront Park, a terraced green space where Lower Broadway meets the Cumberland River. Police made just two arrests this year under the law prior to Oct. 29. News of state troopers’ sudden enforcement of the public camping ban quickly spread through the unhoused community, many of whom see the ban as a powerful legal weapon wielded by officers.

“They are targeting us homeless,” says Dennis, an unhoused man who uses a wheelchair and did not share his last name. “I can’t even move anywhere without help. They picked me up when I was passed-out, down at the cabin.”

Dennis says troopers arrested him and others at Fort Nashborough, the reconstructed log cabin that stands downtown on First Avenue as a historical monument to Nashville’s founding.

“It’s not anything that I’m aware of, but that’s not to say that hasn’t happened,” says Lt. Bill Miller, a spokesperson for the Tennessee Highway Patrol. “It might have been the Capitol protection unit, or troopers from the Nashville district. State troopers have jurisdiction anywhere in Tennessee, as we are a statewide law enforcement agency.”

Over the past four years, state lawmakers upgraded penalties for public camping in two strokes. In the midst of ongoing racial justice protests at the state Capitol (co-led by current state Rep. Justin Jones, elected in 2022), legislators upgraded unauthorized public camping from a misdemeanor to a class-E felony. That charge carries up to six years in prison and a fine up to $3,000. The GOP-controlled legislature went further in 2022, passing additional legislation pushed by state Sen. Paul Bailey (R-Sparta) that more directly makes camping while homeless a felony. At the time, Gov. Bill Lee declined to sign the legislation — a symbolic gesture — stating that he feared the bill’s effects on homeless people. But Lee didn’t veto the law, allowing it to take effect on July 1, 2022.

Residents living on the street share the sense that they live at the mercy of troopers and police.

“To be arrested for camping on public land, you have to meet certain criteria — you have a source of food, water, a place to sleep on, a means of shelter, everything like that,” says Daniel, a 40-year-old man who lives outside in downtown Nashville, as he pushes a shopping cart full of clothes and personal belongings. “I can lie down in the grass and go to sleep, but [if] I have my stuff with me, they tell me to get the hell out. They say I’m camping, or impeding a walkway, or trespassing.”

Debate over the bill also garnered national attention when one lawmaker referenced Hitler while voicing his support

At McKendree United Methodist Church, a congregation on Church Street with substantial homelessness outreach, John Graham explains that living outside means navigating power dynamics and constantly shifting territory.

“They won’t let you sleep anywhere, even for a couple hours,” Graham, who juggles three jobs, tells the Scene while he waits to use the bathroom outside McKendree’s alleyway entrance. “They wake [you] up and tell you to keep moving. The hotels, the diners and the bars don’t want homeless people in there. They close their public restrooms to us. That’s why the streets smell like piss. Meanwhile these hotels have a hundred empty rooms.”

Different people have different theories about the sudden push against homeless people sleeping outside. Some peg it to the CMA Awards, a star-studded ceremony that took place Nov. 20 at Bridgestone Arena. On Nov. 21, Mayor Freddie O’Connell denied local involvement in the crackdown on WPLN’s This Is Nashville.

“Everyone’s cracking down on homeless people because they’re tired of giving out warnings,” says one “Downtown Ambassador” who declined to give her name. The Nashville Downtown Partnership employs a corps of these Segway-mounted guides to patrol downtown.

In the immediate term, the spate of public camping felonies has driven more people into Davidson County jails and courts. The nonprofits, government agencies and individuals involved in the expansive homeless services landscape now include Davidson County prosecutors weighing whether to punish poverty or look the other way.

“Each offense is evaluated on a case-by-case basis,” DA spokesperson Ken Whitehouse tells the Scene on Friday morning, an hour before three camping cases are set to come up in front of Judge Allegra Walker. “Since they are pending, we can’t speak on the specifics.”

In one case brought Friday, Assistant District Attorney Jenny Charles isn’t pursuing felony charges. The DA’s office brought in the Office of Homeless Services to coordinate with defendants, who were released from custody Friday with court dates the following week.

“I think we can all agree that a class-E felony is an overreach, but I don’t think the answer is returning her to live under a bridge,” Charles wrote to one individual’s public defender the day before three camping cases came up in court.

During a recess, a court employee made a passing comment about how Riverfront Park seemed like a preferable place to sleep for someone without any alternatives. She wondered aloud if the troopers in the room would arrest her.

“I turned my own brother in,” a trooper responded.