This year’s state legislative session was a big one for foster care and adoption reform.

Three laws passed bringing forth a substantial list of changes meant to expedite the adoption process for children in the foster care system. Timing was ripe, with the reality that Tennessee’s abortion ban, which went into effect last year, will lead to more children in state custody. Local advocates and those with lived experience hope to strike a balance to provide more stability for these kids, foster parents and birth parents, while acknowledging the trauma implicit in the experience.

A new law shrinks the finalization period for an adoption from six months to 90 days. Also, an adoption cannot be overturned past nine months after it is finalized. (The period was previously 12 months.) Birth parents are now entitled to counseling for two years after the birth, and the law clarifies that the counseling can be offered virtually. Another law allows families to travel to a neighboring county to complete court hearings if their county’s docket is backed up. In addition, it requires that the Tennessee Department of Children’s Services prioritize family placements for the first 30 days, so biological family members can’t necessarily come out of the woodwork months later to gain custody of adoptees. It gives foster parents the option of a respite period, more say in court and more weight when deciding where the child will stay if they’ve had the child for six or more months. Another law cracks down on illegal adoption facilitators.

Sen. Ferrell Haile (R-Gallatin) has pushed for adoption and foster care reform for years, and acknowledged that the abortion ban plays a role in the political will to pass such laws this session. Haile also sponsored a bill that would allow for abortion in cases of rape and incest, which failed this year.

“If you’re more pro-life [than anti-abortion], you try and address both issues,” Haile tells the Scene. “I don’t see that they conflict with one another or interfere with one another. I can chew gum and walk at the same time. I think we can approach both sides to this equation.”

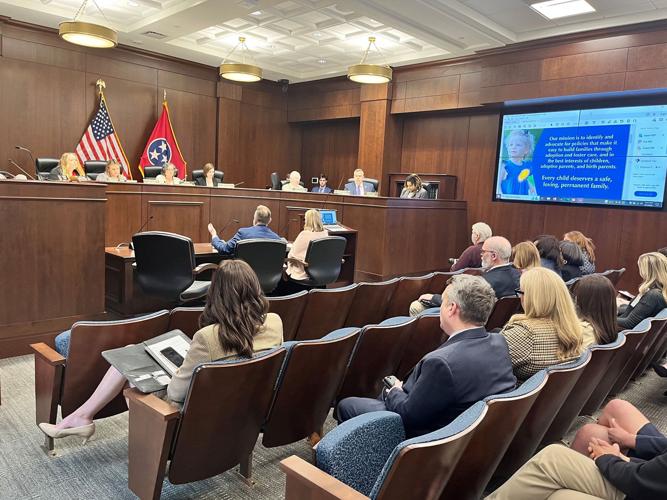

Jeremy Harrell testifying before the Children and Families Subcommittee

The Adoption Project, which launched in 2022, was active in writing the legislation. Another piece of the puzzle to the success of this legislation, says co-founder and adoptive parent Jeremy Harrell, is that many organizations that focus on adoption and foster care don’t have the bandwidth for advocacy.

“They are just doing all these really, really great things, but they’ve all been operating in a system that really could be better,” Harrell says. “Nobody has had the time or resources to dedicate specifically to the policy side of it. That’s what we do.”

Pamela Madison is the CEO of local private adoption agency Monroe Harding. Madison says the legislation is great on paper, but hopes to see it work in practice. Waiting on court dockets and for certain timelines to run out before an adoption becomes permanent produces anxiety for the foster parents and the kids. The changes from this year’s laws could help quell that, she says. The state had a need for more foster parents, especially for older children, long before the abortion ban went into effect, and Monroe Harding offers classes and counseling for interested parties.

Pamela Madison, CEO of Monroe Harding

“We obviously want to give the birth parents time to do the things that they need to do in order to regain custody, because that is the ultimate goal of foster care in the majority of cases,” Madison says. “We also recognize that the process can drag on, and when it’s obvious that the birth parents are not going to do what needs to be done in order to create a stable home for the kids — we really wanted to see that process speed up to create some type of permanency for the children.”

Star Ramos-Colwell, who entered the foster care system at 6 years old after her father was incarcerated, worries that these changes will be unclear for children. She was in 11 different foster homes between the ages of 6 to 10 before finding her foster mother, who adopted her when she was 28. Adoption was a process she needed more time to warm up to, and she’d like to see counseling for children included in future legislation.

“I know as an adult looking at this bill, it’s great that times are being shortened and that the children are able to get out of the situations and that it doesn’t take a really long time for adoptive parents to adopt,” Ramos-Colwell says. “But as a child thinking back on that — that’s a scary thing. Because even though you’ve been abused, even though you’ve been traumatized, you still hold those connections really close, whether it’s your mom or your dad or the kinship — you still really love those people, even if it wasn’t the best situation.”

Harrell and The Adoption Project hope to drive additional legislation while taking into account the trauma that comes with children separated from their birth families to begin with.

“I’m so glad they’re here, and they’re a gift to me,” Harrell says of his adopted children. “But to get here, they lost the closest connection they’ll ever have. It’s important that we are making sure that we’re recognizing all of those things.”