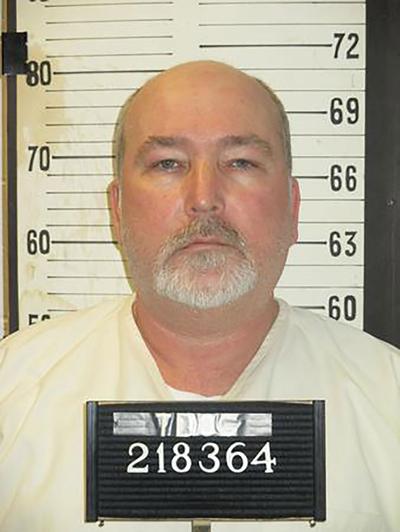

Gary Sutton

For Tennessee’s death row prisoners, the executioner’s clock started ticking again earlier this year when the Tennessee Supreme Court set execution dates for two men. All condemned inmates live with a grim countdown of sorts, but for a time the pandemic brought a pause to Tennessee’s execution schedule. Now the state looks ready to resume regular programming in the death chamber.

The two men set to die next are Oscar Smith and Harold Nichols — on April 21 and June 9, respectively. Both men had been scheduled for execution in 2020 before their dates were called off due to COVID-19. Smith was sentenced to death in Nashville for the 1989 murders of his estranged wife Judy Smith and her two sons, Chad and Jason Burnett. He has always maintained his innocence. Nichols was sentenced to death in 1990 for the rape and murder of 21-year-old Karen Pulley two years earlier. He also confessed to a several other area rapes.

Those men’s legal teams will fight to see their lives spared until the last minute, and advocates — few though they may be — will urge Gov. Bill Lee to grant them clemency. But the reappearance of execution dates on the calendar has brought a renewed sense of urgency to everyone on the row.

Gary Sutton was convicted and sentenced to death — along with his uncle James Dellinger — for the 1992 murders of Tommy Griffin and Griffin’s sister Connie Branam. Authorities said Sutton and Dellinger killed Griffin after a long night of drinking and killed Connie the next day after she’d started looking for her brother. Both men were convicted of Branam’s murder in 1993, and convicted and sentenced to death for Griffin’s murder in 1996.

The state sought an execution date for Sutton, along with eight other men, in 2019, but the Tennessee Supreme Court has yet to set one. Knowing that could happen at any time, Sutton’s family and other advocates have been increasingly desperate to get the word out about his case.

Sutton and his advocates maintain his innocence and argue his trial was unfair because, among other things, he and Dellinger were tried together and his attorneys were inexperienced lawyers who gave him an inadequate defense. Prosecutors never established a motive for Griffin’s murder, and their case was largely circumstantial — Dellinger and Sutton were the last people seen with Griffin. Both men’s attorneys have also suggested other possible suspects and argued that Sutton and Dellinger have intellectual disabilities.

Sutton’s attorneys have brought particular attention over the years to the prosecution’s use of discredited medical examiner Charles Harlan. The former doctor was forced to resign as Davidson County’s top medical examiner in 1994, and two years later, the state of Tennessee declined to keep using him as the state’s top forensic expert. In 1996, as he was serving as an expert witness in Sutton and Dellinger’s capital murder trial — testifying about Griffin’s time of death — he was under investigation by the state for misconduct including faulty and dishonest work. In 2005, his medical license was revoked after the Tennessee Board of Medical Examiners found him guilty of 20 counts of misconduct.

All of this and more, Sutton’s family and advocates believe, contributed to Sutton being wrongly convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a man they say was a close friend.

“I just don’t believe he could do that,” Sutton’s brother Jimmy tells the Scene. “That boy was one of his best friends. He used to bring him food every night to make sure he ate.”

Carolyn Miller had been dating Sutton for about nine months at the time of his arrest. She recently reunited with him — she was over at his family’s house for the Super Bowl last year when he called, and has been visiting him again ever since.

“That was all it took, was for me to hear his voice, because he’s innocent and I know he’s innocent,” Miller says. “I knew it then. I’ve known it all these years, I know it now, and it’s just not right.”

She says she’s surprised that Sutton isn’t bitter.

“When I reconnected with him and started talking to him again — he doesn’t have any hate in his heart,” she says. “I was surprised. I thought he would be really just cold and angry, but he’s not. He’s just not. I mean, I would be.”

Sutton’s family has now spent decades carrying the belief that he is on death row for a crime he didn’t commit.

“It’s been a burden,” Jimmy Sutton says. “It’s affected us, our kids — when they were growing up at school, it affected them, people looked down on them. It really affected us real bad.”

Now, with executions set to start up again, they know time might be running out.

“Any day,” Jimmy Sutton says, “they could call him up.”