Historic flooding on March 27 and 28 of last year had a profound impact on Middle Tennessee, and specifically South Nashville. Six people lost their lives in Davidson, Maury and Cheatham counties, and more than 100 needed to be rescued from dangerous currents and rising waters. Flooding also had a significant impact on the local homeless community, with two residents of a homeless encampment at Seven Mile Creek losing their lives and many others displaced.

For most of those affected by the flooding, immediate recovery efforts were just the beginning. In October, seven months after the flood, volunteer organization Hands On Nashville had already logged roughly 5,000 volunteer hours rebuilding homes and giving assistance to flood survivors. By January, they had helped 579 households, with individual household needs varying significantly. According to HON’s statistics, 429 households required connections to community resources as well as support filling out applications for FEMA assistance and flood insurance compensation. One-hundred-fifty additional households required more significant case management — in addition to volunteer construction, Hands On Nashville also connected flood survivors to supplies and furniture, employment assistance, transportation and psychological counseling.

While the initial volunteer effort after a disaster is often significant, the road to recovery for flood victims is long. And with increasingly frequent severe weather events likely in Nashville’s future, Hands On Nashville is looking to shift the city’s perspective. To Matthew Anderson, HON’s disaster relief construction manager, the rebuilding effort is just one part of a larger process — a way to train a city that is poised for increasingly frequent disasters.

“The culture is changing from sitting around thinking, ‘Oh, I hope we don’t get hit,’ to ‘I need to be ready for when I get hit,’ ” says Anderson. “That, I think, is a really positive step forward.”

Anderson credits Volunteer Organizations Active in Disaster — a coalition of community groups that work together to provide aid after disasters — with the speedy response in 2021. Disaster response is “a really long process,” he says, “but in Nashville, the fact that we were able to get the process up and underway so quickly has helped.” VOAD was formed after Nashville’s historic 2010 flood and was meant to reconvene in March 2020. No one could’ve anticipated reorganizing during a tornado response — or a pandemic.

“They had to launch in a way that they weren’t really expecting, which was while responding to a disaster,” Anderson says. VOAD proved instrumental to the city because it connected many types of community aid in a centralized way, creating a more efficient response as Nashville navigated other disasters, like the Christmas Day bombing and the 2021 flood.

Unfortunately, severe flooding is expected to continue. In 2017, Bloomberg reported that Tennessee’s major cities have experienced “more intense” extreme rainfall events, and warmed by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1950. The Pew Charitable Trusts found that flooding occurs every 10.2 days in Tennessee on average. Instead of mitigating the effects of flooding, infrastructure in parts of Nashville has made the effects more severe. Loss of natural floodplains, erosion and new construction have removed natural flood barriers around the city. “So many places that used to absorb the water … are now being built on,” says Anderson. “And there’s just concrete now, so there’s nowhere for the water to go.”

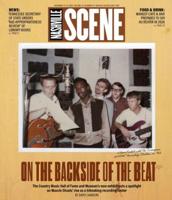

Homes along Seven Mile Creek being raised to prevent further flood damage

That said, Nashville does have significant structural mitigation systems in place. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimated that during the March flood, existing dams prevented $1.8 million in damage by controlling the water level in the Cumberland River. There are local solutions too, like the Home Buyout Program, through which homes affected by the same type of disaster multiple times are purchased and the lots converted to green space. In April, the Scene’s Stephen Elliott reported that the Metro government, alongside federal partners, had bought and converted about 400 houses. The converted green space now works to absorb flood waters.

Still, areas of Nashville like Seven Mile Creek flood consistently with heavy rain. Anderson says flooding disproportionately affects low-income citizens, who sometimes don’t know they’re moving into a floodplain. “The first time they realize it, often, is when water is coming up,” he says. This, combined with “outrageously expensive” flood insurance, creates devastating effects for families — and entire neighborhoods.

“Floods aren’t really ‘attractive’ disasters,” he says. “There’s not huge swaths of destruction you can see everywhere.” But in places like Paragon Mills, he says “it kind of looks like a mouth with broken teeth, where all of a sudden there are a bunch of houses that no longer have people in them.”

There are large-scale solutions to mitigate flood risks — for instance, construction that allows for the absorption of water, increasing green spaces and authorizing new dams for flood control. Anderson says there have been discussions about reinforcing riverbanks, which has proved successful in parts of New England.

In the meantime, adapting to increasingly frequent disasters is a piece of the puzzle we can control. To Anderson, that means a shift in how we understand our relationship to the recovery process — and our own preparation.

“I’d love to see people understanding that we’re going to be living in a state of near-always disaster recovery,” he says. “That’s a really important part of the process — getting people back home, getting people back on their feet.”