In another time and place — say, about 100 years ago — what the guys at Porter Road Butcher are doing would be wholly unremarkable, not the trend of the moment in food.

Walk into the place, a former gas station turned barbecue joint turned house of meat on Gallatin Road, and you'll find a pretty simple setup. Customers are greeted with a chalkboard sign: "Welcome to Porter Road Butcher. We are a whole animal butcher featuring locally sourced, pasture-raised animals. Specific cuts will vary from day to day, and we are happy to suggest alternatives."

The shop used to post a price and cuts menu. But the two guys who run Porter Road, James Peisker and Chris Carter — friends, chefs and now partners in one of East Nashville's hottest small businesses — erased it soon after opening this past December. That came when they realized 1) people stared at the menu instead of asking questions, and 2) they often didn't have all of the cuts available for sale.

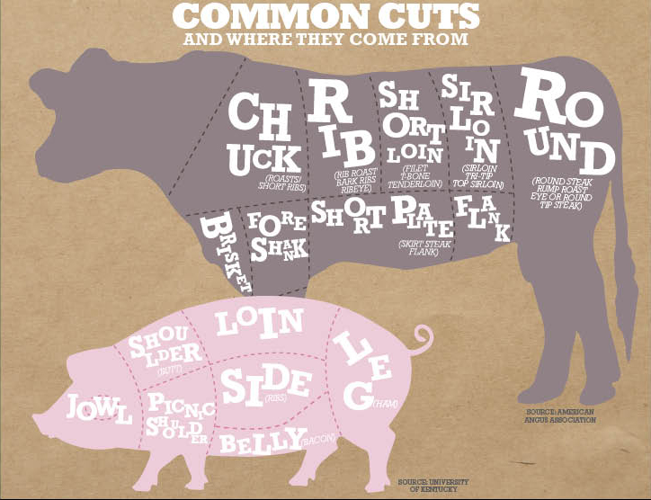

That's the downside of being a whole-animal butcher, as opposed to a supermarket that can replenish indefinitely. When the ribeyes are gone, they're gone until the next cow comes the following week. See what they've got in the display case? That's what they've got prepared. If you want something else, ask and somebody will cut it for you fresh.

The week before Steeplechase was typical. A warm spring meant that folks had fired up their Webers, Eggs and smokers long before the typical Memorial Day grilling-season kickoff. Most customers were looking for something that would work over an open flame.

A guy came in looking for brisket. How big, he's asked. "About 3 pounds." Anything else? "How is the beef finished? Do you have any grass-fed beef?" Next week. He looks around to make sure his young daughter isn't listening. "What about lamb?" he says in a hush. Yup, they can help him out quietly. He's relieved: "She's a sheep lover and wouldn't want to hear about it."

The next person needs St. Louis ribs, a brisket and two whole chickens. And maybe some ground beef. Do they grind to order? "We grind all day. We'll make it real delicious," James says. It's kind of hard for the hamburger meat not to be, as it's an Angus crossbreed that's been dry aged (i.e., hung to dry for several weeks, a time-consuming process typically reserved for the finest cuts). Pink slime this isn't.

Seeing James' Cardinals hat, the customer stops talking meat and the conversation shifts to baseball. It's a busy afternoon, and yet this kind of interaction is just what James and Chris envisioned when they started planning the place, back during whiskey-fueled late nights on Chris' front porch over on Porter Road (originally the street where they planned to open; hence the name of the shop).

They wanted a low-key place where people come in to visit as well as to buy. Sometimes that conversation is an idea — I know you wanted ribeyes, but how about a flatiron cut instead? — or a recipe. It's kind of handy to have guys behind the counter who have spent time in some really good restaurants before.

"I love having a conversation with somebody about what they can make," Chris says, his eyes lighting up a little. "I love to pull out the pen and scribble a recipe on the package. I hope whoever I wrote out that short-rib braise recipe for liked it and kept the butcher paper, bloodstain and all."

"Not only are we selling this pastured, healthy meat, we want to make customers feel welcome," James says. "We want to bring back the essence of the butcher shop. It's almost like a bar with no booze. We've got meat instead of booze."

Just as Nashville seems to be embracing the premium concept in cocktail and coffee culture — higher prices for small batches, artisanal quality, and painstaking preparation that yields dividends in taste and enjoyment — customers are finding their way to Porter Road's East Nashville outpost, seeking cuts and flavors they may never have experienced before.

The butchers at Porter Road cut meat out of whole animals, breaking them down into something you and I might recognize as a chop or a steak. With the rest, they make sausage and bacon and jerky. They find increasingly inventive uses for leftover parts, making sure no piece of the beast goes to waste — and they do it really well. Were this 1912, not 2012, that would be the rule, not the exception.

But the fact that the folks at Porter Road Butcher routinely sell out of everything in their cases probably says more about us than it does them. No matter how good Porter Road's product is — and let's be clear, some of it is toe-tingling, light-up-your-tastebuds fantastic — the larger fact is we're simply not accustomed to what quality meat actually is.

We're buying our steaks in the discount section from places like Costco and Kroger and Walmart, from retailers so far removed from the source of the meat as to be laughable. That "great for grilling" sticker that caught your eye? It gets stuck indiscriminately on everything, including roasts and other cuts that actually aren't that great on the grill.

A hundred years ago, before the development of mass refrigeration helped major packers like Armour and Swift start shipping meat throughout the country, you walked into the butcher shop and had a conversation. Not only could the butcher suggest a cut, he could tell you who raised the meat. It was a far cry from the E. coli scare in 2011 that prompted Tyson Fresh Meats to recall 65 tons of ground beef sold at Kroger and other stores. That suspected contamination couldn't be pinpointed to a single source.

Those earlier days are what Porter Road Butcher hopes to bring back: the days when customers knew what they were being fed, who was feeding it to them — and why it makes a difference.

"We don't have these experiences anymore," says Peisker. The way he says it, wistfully, makes you wonder if he was born in the wrong era, one where your food purveyor was also a neighbor. "We don't have butcher shops," he explains. "We don't have bakeries now. There's nothing greater than walking into a bakery and smelling that smell."

From that longing, a couple of chefs got the idea to open a butcher shop.

James and Chris met in 2010. James had come to town from St. Louis with his longtime girlfriend Marta as she began Ph.D. work in organic chemistry at Vanderbilt. Chris was back in Nashville after a few years in Memphis and Arizona, a former defensive lineman from Hendersonville who got hooked on making food. They both wanted to be chefs and pursued degrees at the Culinary Institute of America and the Le Cordon Bleu schools respectively.

The two say they hit it off almost immediately while working for Capitol Grille's celebrated chef Tyler Brown. That led to the inevitable question, "What could we do together?" But the immediate answer — open a restaurant, of course! — morphed into something very different as they ran through 15 business plans.

All that prep work forced them to take a hard look at the Middle Tennessee foodscape. If Peisker and Carter opened a restaurant, where would they get their meat? That question led to others — and they didn't like what they learned.

The simple fact of the matter is that because cost plays such a huge role in the restaurant business, many places just don't start with great meat. For every high-end place creating relationships with farmers to get heritage breed pigs, for example, there are 10 more taking whatever some other large provider can get them the cheapest.

"Sysco does have some good products, but it's not up to our standards," James says.

Meanwhile, around the country, there's a quiet trend of chefs becoming butchers. For some, it's a life stage, as the horrible hours and stress of running a restaurant aren't always conducive to a healthy family life. But the pair say that's not the reason — they actually miss the pants-on-fire adrenaline that comes from being in the weeds during a busy restaurant shift.

No, they say they want to change how people look at food, and sometimes that means butcher paper instead of white tablecloths. Porter Road arrives at a time when more and more restaurants are exploring the idea of "nose-to-tail" dining, using every part of the animal. In part, it's a move that allows chefs to flex their ingenuity on less familiar cuts of meat (which also often happen to be cheaper). But it also offsets some of the waste that occurs in meat production, making sure more of the slaughtered animal is used — a moral as well as practical concern.

That's one reason Porter Road's butchers are crazy about their work — maybe a little too crazy, sometimes. During his honeymoon in November on a beach in the Dominican Republic, James spent much of the time reading a book on cuts of meat.

That passion, plus their restaurant experience, was what they carried with them when they took their Porter Road business plan to a bank. "A lot of people looked at us funny," James says. Eventually, though, he says they were backed by a group of private investors "who believed in us."

"Our health will change if we change what we eat," James says. Flipping the bromide, Porter Road wants people to live to eat instead of eating to live — to carefully consider and choose the quality of foods they consume, increasing their pleasure while decreasing their intake of chemical enhancers.

If that sounds a little naïve — they're one 1,400-square-foot shop versus infinitely larger supermarkets and warehouse stores — they think the tide is shifting their way.

"We came to the realization that why we are buying all of this from grocery stores? Local markets are gonna be bigger in the future," James enthuses. "We just happen to be here now."

But that means Porter Road's handling of the meat is only part of its mission. To secure the kind of quality they want — and to bridge that relationship between provider and customer — they've got to venture beyond a meat locker to find their product. They've got to find suppliers as dogged, committed and exacting as they are. And that brings challenges as well as rewards.

[page]

A visit to David Byler, the Amish farmer who raises the pigs for Porter Road, is an ass-numbing experience. I rode on top of a metal table, the third person in a truck with only two seats. The refrigerated truck, like their shop, is a bit of a reclamation job. They picked it up third- or fourth-hand for $3,500. The truck was sitting in a ditch when they bought it, and it still has "Bob Evans" written faintly on the side.

As driver, Chris controls the radio, so the music veers somewhere between a podcast of This American Life downloaded to his phone to Tom Petty. Right now, our soundtrack is a cassette tape of Dylan's early '80s, reggae-influenced Infidels, an album Chris got attached to while working promotions at 107.5 The Pig, a jam-band station in Memphis.

An hour and a half later, we arrived at the farm, hopped out of the cab, and stepped back in time. Byler is running a sawmill with some brothers and a couple of neighbors, turning hickory and oak logs into boards. As we walk up to his father's house, it's obvious that we are the oddity here, not the folks in straw hats without electricity in their homes.

Before we can get out to see the pigs, the subject of chickens comes up. Chris and James would love to have another provider, especially in the winter when it can be harder to get fresh chicken that isn't raised in small cages. Beyond that, you've got to pick the right kind of birds. Chickens come in a large variety of sizes. Some are bred for specific things — plump breasts, good legs and wings. The industry is geared for large ones.

The Bylers produce a brochure from Mt. Healthy, an Ohio-based hatchery that says it is the "home of the healthiest chicks." After flipping through and picking out a couple of breeds, they outline a price, one that will push the final consumer price well north of anything you can buy in a supermarket.

For Chris and James, it's worth it. They're not competing with Kroger or Publix based on price per pound — that would be suicide. They make their money on being able to tell customers that not only do they know the farmer, they've also seen where the chickens are raised and what they've been fed. To be sure, the cost difference is notable: Chicken on special at Kroger can run as low as 99 cents per pound, while Porter Road sells theirs for $4.99 per pound. But at a time when Big Chicken is asking the USDA to kick out inspectors and let industrial poultry suppliers self-inspect their slaughterhouses, while ramping up processing speeds to "upwards of 200 birds per minute," paying more per pound for quality assurance doesn't seem like such a big cost.

"People say it's elitist food, and that's bullshit," James says. "People spend hundreds of dollars getting their hair cut and dyed."

Porter Road would like to start selling duck, too, but there's no way to do it without ridiculous transportation costs. These are already not cheap, because any chickens from the Bylers have to be processed in Florence, Ala., or Bowling Green, Ky. The nearest duck processor is in North Carolina. "It's the feathers," Chris says. "They put them in these plucking machines and the chickens lose 90 percent of their feathers. Ducks only lose about 50 percent." That requires more plucking by hand. The chefs hooked up with Byler through their egg guy, Jerry, at Willow Farms in Summertown, Tenn. Jerry acts as their liaison, going over to deliver the occasional message because the farm doesn't have a phone. James admits this can be "a real pain in the ass sometimes."

Nevertheless, he says a conversation with David Byler got the ball rolling: "We started talking to him about what he fed the hogs. 'Corn.' Well, where did you get it? 'I grew it.' " A light went on for the butchers. This was the kind of place they could feel comfortable getting their meat.

Walking back to the pasture where the pigs are raised is a little like walking onto the moon. What had begun as a few acres of land thick with scrub, small trees and grass is now almost completely barren, devoured by the swine. The farmers supplement the pigs' grazing with troughs of corn and feed. But the hogs love rooting out every living thing in an area, so David and his brothers will move them into an adjacent field they recently finished fencing.

As we step through the barbed wire, the pigs scatter. (If they ever realized that each of them outweighs the four of us, it might have gone a little differently.) Standing inside the pen, the Duroc and Berkshire blended pigs keep their distance until one comes up to sniff Chris. They're cute — think Wilbur with big floppy ears — but their cuteness ends about the time one wanders up and takes a nibble of his shoe. Hey, everything else in the field is fair game, right? Chris shoos them off and they flee.

David takes the boys through delivery dates and processes as we walk over to his house, sandwiched between pig and cow pastures. As we step inside, it's 15 degrees cooler, even without electricity. The windows are open, and the fly strip, some 20 feet long and running the length of the kitchen, is doing a booming business. David's wife produces some instant coffee and a roasting pan full of cookies she's made, and the three sit down at the table to talk business.

More pigs? Sure. The boys would like to try finishing a couple of pigs with acorns, maybe ending up with the buttery texture Spain's Iberian pigs are so famous for. Could they take a look at the new feed he had delivered from the co-op? David wants to make sure he's doing everything they need. As they talk, various children from the Byler families file into the kitchen. Quiet and well-mannered, they just stare at us. If the pigs were a novelty for us, we're certainly the most entertaining thing the kids have seen in a while.

When David shows Chris and James the new feed he's bought, there's a problem. There's an unfamiliar protein buried in the list of ingredients, and that just won't do. Chris says he will call down to the co-op in Lawrenceburg and get the right feed. They also agree to build it into the price they're going to pay for the hogs, so David won't lose any money on the bad feed. In the grand scheme of things, it's a few bucks more that will get passed along to some chops or shoulder, but worth it to do things the right way and take care of their farmers.

I ask about being organic. James says it's a lot less important than being right — natural food, no antibiotics, no hormones. None of their guys are considered "organic."

"It would bankrupt them," he says. There are too many hoops to jump through to be able to use the organic label. If they can do things the right way, having a sticker on a package won't matter.

"We all make money together. We all flourish together. We're not making it more difficult for each other. The reason why our prices are higher is because we pay our farmers fairly. Our pig farmer makes a living off of selling pigs to us. We sell their meat specifically and we pay them accordingly."

On the way back to the shop, they stop off at Cattleman's, their processor. It's little more than a cinder block cooler, halfway between Columbia and Murfreesboro. They run a couple of hogs — which we pick up — and a side of beef through here every week, making Porter Road the slaughterhouse's third-biggest customer.

Today's run will be about 180 miles round trip in a truck that's costing them a buck a mile to operate. By the time we hit the interstate and head back into Nashville, the coffee supply is exhausted, the windows are down and both guys are trading yawns. Chris checks the temperature in the back of the truck and hits a button that drops it a few degrees — a fan kicks in and blows air over a frozen metal plate, keeping things well under a safe temperature.

The high truck cab provides a funny vantage point for people-watching. Chris said he's seen everything going back and forth to Cattleman's. "For the most part, everybody drives with their pants on. ... For the most part."

As we pull into the shop, the six-hour round trip has pushed us just past noon. James stretches his neck and tries to wake up. He's got another eight hours of cutting to do before he can think about leaving.

It's safe to say the pair seem to be outpacing whatever was in that 15th business plan. Though they are Porter Road's founders and mainstays, the shop doesn't run on just those two.

Market manager Leslie Gribble has been with the boys since before they started. Same with Chris Hudgens, a longtime friend of Chris and his girlfriend Kelly (who, sadistically enough, is a vegetarian). Hudge has become almost exclusively a sausage guy now, such is demand. Between their charcuterie for nearby restaurant and bar No. 308, the andouille sausage and whole hog work they do for Merchants, and the sandwiches, sausage and biscuits they make for nearby Barista Parlor — a new coffeehouse around the corner that, in its attention to detail, process and quality, could be the Porter Road Butcher of single-cup brewing — everybody is working at capacity.

The four of them eventually expanded to six or seven with a couple of "stages" — the French term for "intern," although in the wrong place it can also be translated as "slave." I ask about Zach and Kyle, the current stages, whom the butchers seem to like. What are their last names? "Stages don't get last names," I'm told.

The work for restaurants has been a nice surprise, a recognition that they're doing things right. The finished products are also good value added for the whole animals they're using. Think about it this way: When a 1,300-pound Angus blend comes in at 900 pounds from the processor, they've already lost part of the cow they've paid for.

Almost every bit of the rest of it has to count, so there's a lot of stock-making and bone-roasting going on. And when the most popular 20 percent — the tenderloins, the ribeyes and the strips — is gone, the rest of that cow (or pig or lamb) needs to become something delicious. If it doesn't, Porter Road isn't going to last very long.

Sometimes that takes a little creativity. Everybody loves braised short ribs in the winter, but in the summer? They just aren't moving. So the butchers turn short ribs into hot dogs — fantastically delicious wieners that make it hard to go back to Oscar Mayer or Ballpark, retaining their succulence and beefy richness even roasted in a breakroom toaster oven. They've worked similar wonders with shanks, which lately they've been turning into confit beef-shank orzo salads.

A few things are just over the top. The bratwursts — a concoction of salt, pepper, nutmeg, ginger, Hatcher cream and Willow Farm eggs — go pretty quickly. And if the smoker out back isn't finishing some andouille, it's likely loaded up with any manner of bacon. They can't keep sausage in the shop right now. Not long ago they had to cut up an entire pig just to meet demand for sausage.

All of those parts, those pieces, add up to something. Porter Road means to serve as something bigger than the sum of its ingredients — as a small business, as a food provider, or as what the butcher boys think is most important, a neighborhood fixture that decreases the distance between a farmer and your table.

"What we're fighting against is a lot of lies now. 'All-natural' means 'nothing was added,' " James says, incredulous and his voice rising a little. "Why would you add something to raw meat!? We will never lie to you like that."

That indignance may explain why customers are making their way to a meat counter in East Nashville, willing to pay higher prices in return for peace of mind. A famous adage says something to the effect that people who like sausages and respect the law shouldn't see either one being made. By returning in essence to a bygone business model, maybe the novelty Porter Road Butcher has to sell is trust — one link at a time.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.