James Dobson has lived in the same brick ranch house in Edgehill, a historically black neighborhood a stone's throw from Belmont University, since the Eisenhower administration. For five of those decades, the same man lived next door in the same modest home. "He was my neighbor and my paperboy," Dobson says, and together they sat in the shadow of a three-story condo constructed nearby.

But now Dobson has a new neighbor: a mound of rubble where the late owner's house once stood, and out front a lawn sign that reads, "We Will Buy Your Home."

That message has been broadcast to Dobson and scores of Nashville homeowners, who are seeing the value of lots far outpace that of the homes built on them decades ago. Ever since his neighbor's home was razed, developers have been hounding Dobson about giving up his own.

"They keep asking me how much I want for my home, and I always say, 'Nothing. I ain't moving,' " says Dobson, 97, who remains sharp and confident in his abilities. "I raised three kids here, and I want my last days to be my best days."

But as Dobson can attest, real estate investors and speculators are joining the gold rush for new living spaces and the rising value of dirt. In Nashville's hottest neighborhoods, come-ons from companies seeking to purchase are arriving faster than spam.

The correspondence can look official, blaring "notice" in all-caps. "Our company is now seeking to purchase several homes in your neighborhood ... " reads a pitch recently taped to an East Nashville door. A Sylvan Park resident who asked not to be identified says he has received "about a dozen" mailers this year from developers looking to buy his property.

"There's such a surge of opportunity for builders to come into Nashville," says Jim Spangler of Hidden Valley Homes, which posted the sign next door to James Dobson. The company expanded into Nashville this summer from Brentwood, where it builds mostly high-end homes. "We're going to go where the demand is going to be. You're seeing a lot of it in Nashville." Asked how he thinks the city's landscape is evolving, Spangler replies, "I call it revitalization."

That's not the word opponents use.

A debate is catching fire in neighborhoods across the city. On one side are residents who say the imposing new properties hoisted on the graves of former homes — many almost comically larger than what came before — are blighting communities. On the other side are developers, investors and builders like Spangler, who spy opportunity.

Spangler is eyeing lots adjacent to Dobson's where other houses and apartments sit. His company has already leveled three other homes in the area. On all of them, he plans to build cottage-style condos. To show the amount of money at stake, each of those will run about $400,000 — nearly triple the appraised value of Dobson's dwelling.

Call this another verse of the It City Blues: a booming metropolis outgrowing its capacity. According to a statistic often cited by city planners, the Nashville area is poised to add a million more residents in coming decades. The current and expected influx is bringing new business prospects and creative minds to Nashville, showering the city with national attention.

But that only makes longtime Nashvillians more worried about their town losing its unique qualities. Bursts of new activity from Charlotte Pike to Inglewood are reviving age-old debates about the tradeoff between preservation and development. How will we lure newcomers with our "big city with small-town charm" label, teardown opponents argue, when we're bulldozing older homes and replacing them with generic lot-busters?

"Once the ball gets rolling downhill, it can roll extremely quickly," says Vanderbilt urban sociology professor Richard Douglas Lloyd. "We're going to experience some unwelcome consequences: traffic, disruption of fabric of established communities and neighborhood identities, and all of us feeling like it's not easy to live here anymore.

"This is the new paradigm for urban renewal. In a city that's not as vertical as Manhattan, this level of growth can create a fractured and incoherent landscape."

Citizens may be divided over whether they think the next phase in Nashville's growth will be better than the last. On teardowns, however, they seem united — in opposition. Residents argue that teardowns are affecting the rhythm and flow of streets and altering the character of neighborhoods. To be sure, not every house deserves to be saved, and new construction often helps prop up property values (along with property taxes) while attracting new investment.

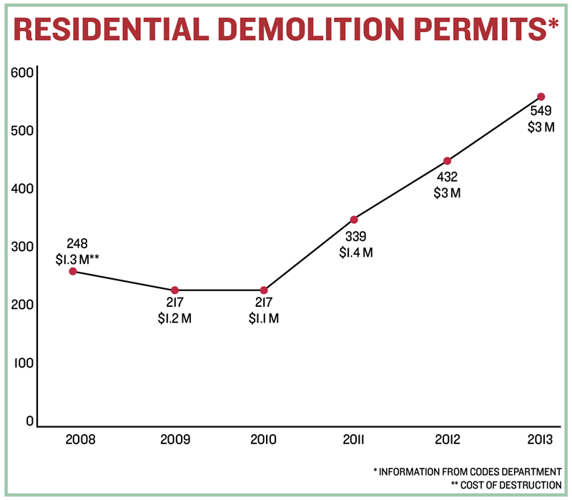

But every time a bulldozer revs into gear on a quiet residential street, the misgivings get louder. So far this year, developers have spent more than $3 million to tear down 549 residential properties. That's more than double the number of demolitions five years ago, according to records from Metro Codes. Home demos started to pick up around 2011 as the economy recovered and the city licked its wounds from the 2010 flood. They've risen steadily ever since.

"We have a tremendous demand for infill development, and that reflects the changing demographics," says Rick Bernhardt, director of the city's planning department. (In other words, that means more affluent people are moving to Nashville and want to live within the city.) "Neighborhoods are changing because land is becoming so valuable."

Detractors say public officials like Bernhardt are biased toward development. To them, this is a replay of the shortsighted planning that razed much of the city's historic downtown in favor of parking lots back in the last century. Advocates say adding properties translates into more tax dollars, which can lead to improved services.

In the middle, most residents see only the short-term growing pains. They wonder if the teardowns, and the boom they embody, will only make existing city ailments worse.

Having lived in the same small white house in Sylvan Park nearly her entire life, Cynthia Newlon has witnessed her share of change. Most of it, she says, has required little adjustment. Neighbors and businesses have come and gone. Gradual growth has been noticeable, but not disruptive.

Adapting to the latest changes has been much more difficult. The house next to hers was demolished recently. In its place stand two slender homes that dwarf her own.

For Newlon, the intrusive new buildings have cut into her quality of life.

"It makes me sick to look out my kitchen window and not be able to see the sky," says Newlon, a retired office administrator approaching 70. "They have a window facing my deck, so there's no more privacy there. And everybody just stares when they go down the street. It doesn't look right next to my little house."

Developers, who stand to gain the most, portray the teardown phenomenon as inevitable. As older homes fall into disrepair or fixing up older properties becomes too costly, they say, it makes more sense to start from scratch. They add that current buyer preferences skew toward new construction — a kind of insurance that there are no hidden quirks or dormant structural issues.

With demand soaring, therefore, and space up for grabs, many areas of the city are now targets for outside developers.

"You're seeing tons of teardowns in 12South, Belmont, Sylvan Park and all over," says Realtor Christie Wilson. "A lot of people have a sort of love-hate relationship with them. People want neighborhoods to keep their charm and cool character, but the land, many times, has become more valuable than the homes sitting on it. And for some buyers, a new small home in a cool neighborhood is far more affordable than a historic one."

What Newlon sees when she looks out her window represents the current hot trend with Nashville developers. It consists of two buildings attached like Siamese twins on one lot. Indeed, the units, often called "skinny duplexes," are connected by a shared space developers call an "umbilical cord."

The trend springs from a quirk in the city's code, which leaves the definition of a duplex rather ambiguous. In neighborhoods around the city's core, any builder can put two structures on a single residential lot as long as they are connected by an 8-foot umbilical cord. When buyers move in, the units are owned separately but the land is owned jointly.

"During the rewrite of the code some 15 years ago, the planning commission unintentionally left out that a duplex had to have a contiguous interior," says former Metro Councilman John Summers, who has done two stints on the city's planning commission. "Nobody caught it. A couple of years later, an interpretation said two-on-one is OK as long as they're connected."

In some areas, such as Green Hills, two-on-one lots can exist without the umbilical cord. Pro-development Metro Councilman Charlie Tygard is among those trying to sway city officials to get rid of the connector altogether. He says the structures it creates are eyesores.

"I don't know there's anybody that has the unique interpretation of a duplex that we have in Nashville," Bernhardt says. "And there are some problems with that." In some cases, he explains, the skinny duplexes are far taller than the homes that abut them, and thus they sometimes look out of place with surrounding neighborhoods.

One solution, he says, is for city planners to make the definition of a duplex clearer to regulate their proliferation, something Bernhardt and his colleagues have discussed. For developers, though, the code quirk often means a two-for-one profit margin. For that reason, there would be fierce resistance from real estate forces in the event of a proposed change — at least one that would limit one structure to each residential lot.

"The two-on-one trend is the wave of the future," says real estate investor Jeff Livingston. "It pencils [pays] for me to build two-on-one all day."

Such talk rankles residents in East Nashville's Eastwood section. On a Friday evening in October, a canary-yellow Victorian home was torn down. The home was nearly a century old; it was demolished in a matter of hours. The demolition struck a nerve with neighbors — especially photographer Gregg Roth, who owns the 1925 Craftsman next door. According to Roth, it was done so hastily that the process broke three side windows on his house and damaged his HVAC unit.

The windows have since been repaired. But Roth and other neighbors remain incredulous at how quickly the home came down. They're even more perplexed by what will soon rise from its rubble: a two-on-one duplex.

"We just thought that if it was that old, you can't just knock it down," Roth says. "It's going to look ridiculous. There's a reason we moved into these houses. This new thing can potentially ruin the reason why we moved here. It's so wrong for the neighborhood, and nobody wants it."

Other neighbors are just as irate. As in 12South, they feel they took a chance on a troubled neighborhood when no one else would, only to have outside developers swoop in to profit.

"The people did a lot of work to turn this neighborhood around, and we didn't do it so a developer can come in, tear down a home and make $200,000," says Dave Jacques, a musician and Eastwood neighbor. "These new duplexes are all over the city now. They're going to look like the brick duplexes of the past. They're going to eventually think: Why did they do that? Whereas the houses being torn down have real shelf life."

As with every teardown story in Nashville, developers and neighbors have different viewpoints. The developer, two-on-one advocate Livingston, says the home had fallen into ill repair, and the financially distressed homeowner did nothing about it. Livingston's first intention wasn't to bulldoze the property, he says, "but it would have cost me extreme amounts of money with an engineer to make it work."

So he purchased, cleared the lot and made plans for something new, to a chorus of protest from neighbors. But Livingston says he did get one note of approval. "I got a personal phone call from the codes department thanking me very much," he says, "since the home had so many codes violations for so long."

Hoping to stave off future developer conquests, Roth and other neighbors say they will ask city preservation officials to include their street in a protected area, known as a historical overlay, which places restrictions on development to maintain historic character. They plan to meet with their councilman, Peter Westerholm, to discuss their next steps.

"These are rough conversations, because not everyone appreciates the same things, or values the same things," Westerholm says. "I don't mind density, but what's being built tends to be larger and out of scale with the neighborhood, and some people think that's too much."

Eastwood neighbors aren't the only ones concerned. According to Tim Walker, who heads the Metro Historical Commission, eight other neighborhoods are now exploring new or expanded overlays. These include Lockeland Springs, Hillsboro-West End, Sylvan Park and Woodmont.

In most cases, historical overlays in Nashville come in two forms: a preservation overlay, which affords the strongest protections, and a conservation overlay, a type of zoning introduced in the mid-1980s that protects properties but is less rigid. Homeowners have been using them increasingly as a way to react to the city's growth.

"It is a response to several issues," Walker says, "including the loss of historic buildings, which can change the character of a neighborhood, and the construction of new homes that are out of scale and not in the character with the existing neighborhood fabric."

Being placed within a historical overlay doesn't freeze future teardowns or development. It simply places another step in the process: having to gain the blessing of historic zoning officials.

But to some developers, that's trouble enough to look elsewhere. Real estate agent Price Lechleiter says he was involved in one redevelopment project where the historic zoning step added about two months to the process. "For some developers, that would not have fit into their timeline expectations," he says.

Generally, homes built before World War II are considered historic. In order for a community to gain an overlay, though, the homes have to reflect an important architectural style or contribute in some meaningful way to the historic character of the neighborhood.

John Summers, the former councilman and planning commission member, introduced preservation zoning 30 years ago as a way to regulate demolitions. He feels the current makeup of the commission lacks a community advocate.

"The planning commission has gone from the concept of neighborhood preservation to neighborhood development," Summers says. "They've always been pro-growth, but it's really accelerated.

"We have places in Nashville that need new development, but builders only go to the high-dollar areas. They overbuild in those parts and impact the environment. Take, for example, Green Hills."

Former Metro Councilman Ronnie Greer, who represented Edgehill, is a vocal opponent of the city's brisk infill development. He said some homeowners, especially older ones on Social Security, often face different outcomes than Dobson when confronted by developers. As new homes start popping up, residents with fixed incomes or limited means sometimes can't afford the accompanying property-tax increases and are effectively pushed out — an almost textbook example of gentrification's perils.

Homeowners caught in this bind commonly accept offers from developers. According to Greer, a friend got an offer from one developer, with a caveat attached: The friend had to convince his neighbors that selling was a smart idea.

"Some of these developers, these new folks with all kind of money," Greer says, "are vultures."

Such transactions have stoked arguments about the effect of rising property values on transitional neighborhoods from East to North Nashville — and whether the teardowns are a symptom or the disease itself. Yet one nuance often missed in these conversations is that opposing gentrification shouldn't be lumped in with opposing development, according to James Fraser, a professor of human and organization development at Vanderbilt.

Fraser has studied low-income communities surrounding downtown Nashville, and he recently met with planning director Bernhardt to discuss how the department can make development more equitable. At the same time affluent newcomers are clamoring for living space within the city — the demand behind the teardowns and two-on-ones — Nashville must figure out how not to take it away from those who have less.

"The 'back to the city' movement that we are experiencing comes at a cost to people who have lived in low-income neighborhoods that are targeted for gentrification," Fraser says. "Largely because we have so few planning tools to use in order to maintain affordable housing stock."

The problem, Fraser believes, isn't development itself. Rather, he says it is that "we have not been intentional about creating truly mixed-income neighborhoods where those who are less affluent can live in desirable places in the city."

Specifically, Nashville lacks policies that encourage low-income housing: units owned by nonprofits or land trusts, working in conjunction with private developers. What's needed is a process that essentially connects real estate people with groups whose main concern is generating quality housing for the underserved, not profit. Such relationships can help keep communities economically diverse, Fraser says.

Planning officials counter that similar regulations have been proposed many times over the past several decades, but they have not passed the 40-member Metro Council. That development-friendly body is better at handling short-term crises, they say, than long-term problems.

Whatever the case, housing advocates warn that rapid development is producing a dire consequence: a growing number of low-income residents getting bumped out of their neighborhoods. According to the Census Bureau, anyone spending more than 30 percent of their annual income on their mortgage or monthly rent is considered cost-burdened. The last time they surveyed Davidson County, census officials found approximately 100,000 households fit that description.

"We need to look at what we can do to preserve affordability," says Paul Johnson, executive director of the nonprofit Housing Fund. "The trick is always how do we make sure we save the housing choices of people who already live there as we anticipate new growth?"

Many advocates point to inclusionary zoning as part of the solution. It's a zoning model that makes developers devote a percentage of new housing units to low-income residents. Developers, in turn, usually receive incentives like looser density limits and other relaxed zoning requirements. In Montgomery County, Md., just north of Washington, D.C., for example, up to 15 percent of new housing has to be affordable. The requirement has spawned around 11,000 affordable units over several decades.

Asked about the prospect of adopting inclusionary zoning in Nashville, Bernhardt says he would welcome it, though state and local politics stand in the way.

"I believe that the time is right to try it, and we probably will in the upcoming year," he says, noting that other cities have passed inclusionary zoning that applies to developments of 50 units or more. That would not have much effect in Nashville, he says, since much of the city's new construction is scattered lot development.

Nashville has had affordable housing requirements in some of its redevelopment districts. The Gulch, for instance, took advantage of tax-increment financing, in which property taxes in a specific area are dedicated to redevelopment. One of the stipulations of using TIF money is that developers include low-income set-asides.

The practice, however, is far from meeting the city's need. "Nashville is seeing a growing gap in affordability," The Housing Fund's Johnson says. "And people are going way out to get affordable housing, but then they just tripled their transportation cost."

From Sylvan Park to Green Hills, as plus-sized houses squeeze into ill-fitting lots like a cartoon hippo in a chorus line, teardown opponents are finding other ways to push back. The Metro Historical Commission's Walker says that in neighborhoods where bigger homes are being constructed, as in some parts of Belmont-Hillsboro, neighbors have started citing lists of ways such structures reduce the quality of life for the entire area. Things like the lack of green space, the absence of sky.

That has become a selling point for smaller units promoting "sustainable" living, which claim that their smaller environmental impact helps retain open spaces. But city researchers like Vanderbilt's James Fraser question the logic behind the messaging.

"The term 'sustainable' does not mean much by itself," Fraser says. "So we have to ask the question: 'Sustainable for what people?' More often than not, pro-growth coalitions of developers, city officials and the business community think sustainability is driving up land value as far as it will go by building housing products that are out of reach for low-income families."

But it's not just low-income families or native Nashvillians who are singing the It City Blues as teardown fever reaches epidemic proportions. It's also the people who came here long before the recent wave of national press, lured by the city's downhome charm and deep roots. Among them is Bob Bernstein, founder and owner of the city's Bongo Java coffeehouses, who moved to Nashville from Chicago about 25 years ago, drawn by a certain, perhaps erstwhile, quaintness.

"For years, I would say I love Nashville because it's an easy place to be," Bernstein says. "Now it's an exciting place to be, but it's far less easy."

That unease recently manifested itself two doors down from his 12South home. There, a home was demolished to make way for a two-on-one structure that, as he sees it, "is going to look like the oddball" on the block.

"It's so out of line with the historic homes on my street," Bernstein says. "It really pushed people over the edge."

Out of frustration, Bernstein, a born sloganeer, started a mini grassroots campaign in the form of yard signs that read: "Build Like You Live Next Door." He's passed them out to about a dozen neighbors, and plans on passing out more. Some developers have profit-maximizing tunnel vision and don't care enough about what neighbors think of what they're building, Bernstein says.

"I don't think development is bad, but the town is changing so fast that there's no discussion about it," he explains. "I'm a business guy. I'm not against growth. But at what cost?"

Bernstein says he moved to 12South from East Nashville once the 15-minute commute to his Hillsboro Village office stretched to a half-hour. Now he's finding that longer and longer traffic delays on the way to his kids' school are the new norm. Like the teardowns and the two-on-ones, it's a sign that where status is concerned, Nashville should sometimes be cautious what it wishes for, or how quickly it arrives. Because when some things are demolished, they can't just be replaced — no matter how big you try to build.

"The city is growing like crazy," Bernstein says. "It's exploding. Being here and being 50 years old makes me wonder, 'What kind of lifestyle do I really want?' It's a decision I'm always wrestling with."

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.