Editor's note: Nashville's public school system has come under intense scrutiny in recent years after nearing state takeover. As the district has wrestled with academic performance, it has also spent the past few years embroiled in schoolyard fights — between the city and state over charter-school laws, among bickering board members and administrators over politics. At the same time, parents with the means to send their children to private schools have fled MNPS, while others have moved across county lines to escape the school system.

As for the kids who are left, many have families who actively dedicate themselves to public schools, often ones of their choice. But they're the lucky ones. Others don't have the economic luxury to choose. The growing strain on resources, the widening demographic changes in Davidson County, the political turbulence behind the scenes, and the number of parents and promising students who have left the system indicate a looming crisis in Nashville public education.

Yet there is reason to hope, and a chance to act. This is the conclusion of a three-part series probing the issues that face the beleaguered school district, the people they affect, and the district's reaches for success. The first story ("Speaking in Tongues," Oct. 16) concerns English language learners and their impact on the school system; the second ("Growing Pains," Nov. 20) addresses overcrowding and its effect on school resources.

On a nippy Sunday morning in November, Middle Tennesseans fished an orange bag out of their driveway, with a rolled-up newspaper inside. As usual, the first thing visible wasn't the front page but the ad wrapped around it. Such ads are traditionally used to sell groceries, or cars — but not this one.

This one was selling a school system.

Metro Nashville Public Schools is spending $44,300 on advertising in The Tennessean this year, including a one-time wraparound ad in the Sunday paper last month. Perhaps selling public education the way you'd sell paper towels or a Taurus sounds desperate. But if people vote with their feet, a third of Nashville parents every year place a vote of no confidence in their local school.

Maybe they choose a more appealing public school a neighborhood over or across town. Maybe they pick a charter school, a private school or home schooling. Whichever the case, according to state, local and school district statistics, 1 in 3 children avoids his or her zoned Metro Nashville public school. And that figure doesn't include the kids whose parents have taken them out of the equation completely — giving up homes with "It City" zip codes for ones outside Davidson County, where confidence in their zoned school is more certain.

Flight from the city's public schools is nothing new. Nashville has a higher portion of students in private school than the national average — a side effect of the city's history of segregation as well as its many religious affiliations. Nashville also has higher percentages of children in charter schools, which are run by independent teams of principals and teachers but funded by the school district. These alternatives were intended to expand parents' options.

Recently, however, they have torn open a rift in the city. Many parents are abandoning low-performing neighborhood schools. Others are taking the opposite approach to keep gifted students and engaged parents within the system. As the heat has risen, the debate over Nashville's public school system has devolved into us-vs.-them political finagling and toxic squabbling about the best paths for education across the city.

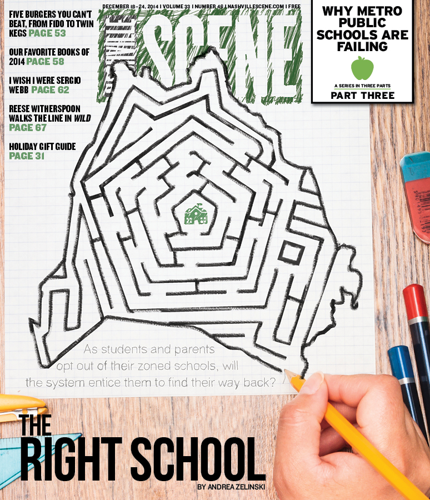

In an effort to understand why so many parents are opting out of their zoned schools, the Scene spoke to students and families who chose different paths for different reasons. In some cases, the path led away from schools altogether. In others, it led students back to public education. What became clear is that for all their differences of opinion and option, Nashville parents and students are fighting their way through the same labyrinth — and for the same reasons.

The Hawes Family

Susan Hawes' brown ranch-style house opens onto the sloping hills of the Shelby Bottoms golf course. On the rare days it snows, kids in the close-knit neighborhood treat the house and its rolling yard like a ski resort. Across the scenic gulch sits East Nashville's Lockeland Design Center, where her two sons have always gone to school.

Lockeland is among the most coveted elementary schools in Metro Nashville — indeed, in the entire state. It's one of eight magnet schools where nearby residents who live in a "geographic priority zone" have first chance at enrollment, followed by a wider swath of East Nashville kids, then kids from the rest of the county.

Hawes' eldest, Henry, 12, got enrolled in 2007, just before the East Nashville neighborhood began tearing down old houses and churning out new ones unaffordable to anyone not at least middle-class. Back then, approximately a third of his classmates were black, Hispanic or Asian in a neighborhood transformed by newcomers who were initially drawn by its diversity. The school, like the neighborhood, grew whiter and more upscale by the time his brother Calvin, 9, enrolled three years later.

Now enough people are sending children to Lockeland that there's no guaranteed seat anymore for neighborhood kids without a slightly older sibling in the school. That means no seat for Josie, 4, the youngest in the Hawes family. Even though the walk to school is less than a half-mile away, the gulf in age between her and her closest brother is too great.

For two years that dilemma has consumed Hawes, a mother of three, substitute teacher and former pre-school instructor. She would wake up worrying: Would she have to split her family into different tracks, where Josey might be the only kid on the block who didn't go to Lockeland? Would that make Josie grow up different from her brothers? Would Hawes have to start all over — volunteering, subbing and navigating another elementary-to-high school pathway, after having poured so much love and effort into her boys' school?

At such moments, Hawes says, she would think: Why is education so complicated here? Maybe they should move out of the county — out of the country, even, someplace where education is easy. Where you know where your kids are going year after year, and you never have to worry about lotteries or the pressure of making the very best choice ... and not just for your own kids.

Nearly half of the East Side's schools are considered low performing by city and state standards. Others aren't far behind. Rosebank Elementary, three minutes away from the Hawes' house in an area of escalating home prices, dodges the low-performing designation even though more than half its students are behind grade level in math or reading. Nine out of 10 kids at Rosebank are poor, 2 out of 3 are black — and nobody on Hawes' block goes there.

Aside from the 113 children zoned for Rosebank who won a ticket into Lockeland and its pathway of schools, 41 children in the neighborhood go to Dan Mills Elementary instead, which is as white as Rosebank is black. Dan Mills has enjoyed revitalized parent support in the past two years: Reading scores are higher, although still only approximately half are at grade level. Another 33 children from the neighborhood go up the road to Inglewood Elementary, one of the city's lowest performing schools.

All told, about 250 students zoned to Rosebank go somewhere else. If everyone were required to go to their zoned school, Hawes believes, Rosebank would be thriving. Well-performing children would lift the school up and add diversity, she contends, and the community would be just as invested as they are at Lockeland.

"It's hugely a racial issue over here. It's liberal East Nashville, so nobody wants to admit it," Hawes says, sharing a glass of fizzy apple juice at her dining room table as the sun sets.

Lockeland feeds into East Nashville Magnet School, a grade 5-12 school near Five Points. More than 3 in 4 children there are black, and just more than a third of students are low income.

"When all of the white kids at Lockeland have a choice to go to middle school and they have a pathway where all 60 of them can go to the same school together right down the street at East — and people drive by East in the afternoon and see that it's about 80 percent black — they start looking elsewhere to send their kids, and no one will say that's why," Hawes says.

Pleasantly surprised after a visit to Rosebank that morning, Hawes says she'd be willing send her little girl there — to invest in the school the way parents at Dan Mills started two years ago; the way families are doing now at Litton Middle School, another revitalized East Side school. But she can't find any other families to go with her. On her U-shaped block, all the children except for one family went through elementary school together at Lockeland. They go to 10 different middle schools now. Nearly 20 percent of students have left the East Nashville neighborhood for a school across town, whether public or private.

"Everybody's angry. All we talk about is the lottery when parents get together ... who's going where," Hawes says. "No one wants to go out on their own and to feel like they're sacrificing their kid."

And she admits she's no different.

"I understand completely that I am an anti-choice school proponent with two kids in choice schools," she says. But she would he happy to not do that, she explains, if only she had a team of parents and kids to take with her.

"It's so stupid," Hawes says. "We have great schools. We're just so brainwashed into thinking it has to be a choice or it's not adequate. The kids who are scoring well score well anywhere. ... It's a cloud that hangs over parents that people don't talk about."

Now she's second-guessing whether she'd be OK if Josey loses the lottery to Lockeland and ends up at Rosebank. With the school district turning nearby Kirkpatrick Elementary — one of the city's lowest performing schools — into a charter, she's afraid problem students will be siphoned to Rosebank if they can't follow the new school's stricter rules.

"I want a stable school year for her, not a new environment every week or month," she says.

If Josie loses the lottery, Hawes might try for Dan Mills, although the school is so popular it's nearing 100 percent capacity. But for now, she's in a situation she considers "ridiculous" — close to one of the city's best schools, the school her other children and the other kids on her block attended, yet dependent on a lottery to tell whether her youngest child can get in. If parents continue to "just keep taking care of ourselves," she says, they will only add to the system's problems in the long run.

"But it's true, it's what we're doing," Hawes says.

Of the 96,000 school-age children the U.S. Census estimates are in Davidson County, 10,080 attend private school. Another 1,280 attend makeshift classrooms at home, taught by moms, dads or family members. Yet another 21,965 go to a public school, but not the one in their neighborhood.

In short, 1 in 3 Davidson County children go somewhere other than their zoned school. Of those who stay in the district, about 5,920 go to a charter school, and 2,150 go to two elite magnet schools that require winning the MNPS lottery. Almost as many go to a specialty school designed to address their special needs or function as a pre-K center.

Some parents and students seek something special, like training in a high school "academy" that focuses on engineering or health care. Some want convenience for commute's sake, or to send their kids to the same school as their neighbors down the block even if the zone lines criss-cross them out. Many choose a school they'd feel more comfortable with than their neighborhood school.

Parents choose schools using fairly similar criteria, according to Claire Smrekar, a researcher and associate professor of public policy and education at Vanderbilt University. In a report, Smrekar observed that these boil down to four categories: academics and curriculum; discipline and safety; transportation and convenience; and religion and values. Of those, academics were considered most important, with safety a close second.

But Smrekar cites studies showing that parents with a college education were "much more likely to emphasize the importance of teacher quality" than parents without a college degree. A similar breakdown occurred between white parents and those who were Hispanic, black or Asian, who focused slightly more on test scores.

Black and Hispanic parents were also more likely to underscore the importance of safety and discipline in schools and a sense of familiarity, she notes, as were parents with less formal education. White or college-educated parents tend to mention values as a higher concern.

"It's almost two bookends of American life," Smrekar says. "You have families with lots of resources and educational experiences that position themselves in a place to gain access to a full array of information, and those decisions are based primarily on what they learn about the instructional quality and high academic performance of those schools.

"And then you have other families — the other bookend of families — who, first of all, they're choosing schools that are accessible to them, that are familiar to them and which they perceive will provide a good education. But sometimes we know that some families choose schools and it's sometimes a curious equation because it does not look like a smart choice."

If school success is measured by student test scores, MNPS is moving the needle in the right direction. Test scores have improved in nearly all subjects and grade levels this year, according to the district, and have posted double-digit gains since 2010. Despite that, more Nashville schools found themselves this year in the bottom 5 percent statewide. These schools are charged with helping students already years behind in reading and math, struggling with poverty and hunger, or facing unstable home lives.

According to statewide results from the annual Tennessee Comprehensive Achievement Program test, which measures students in third through 12th grade, only slightly more than half of MNPS students are at or above grade level. Meanwhile, 73 percent of students struggle with poverty, according to the state Department of Education.

Even so, Joe Bass, a spokesman for the district, argues that Nashville public schools are suffering from an outdated reputation, and that they have transformed for the better over time.

"The question shouldn't be, is it a good school," Bass says. "The question should be, is it a good school for your child."

Toward that end, MNPS is spending $82,390 this year on media advertising, including 10 print ads in the city's daily, more than 450 radio spots and almost 1 million impressions on various media websites. The marketing effort is part of the district's Edge Campaign, encouraging parents to take another look at middle schools, the Music Makes Us program, high school career academies and the district as a whole. Think of it as a public-school version of, "Have you driven a Ford lately?"

"What I encourage parents to do is walk into a school and judge whether your child can be successful there and if you will get what you want out of that school," Bass says. "I always recommend that you look for a school that is good for your individual child."

In some cases, though, the best option may not be a school.

The Utley Family

When Tracy Utley used to shuttle her son Jack back and forth to kindergarten, something inside her hated it. Even though she had two more boys at home (and later a third), it seemed like Jack was never home. And while she says it's silly to overanalyze a 5-year-old, his relationship with his 3-year-old brother — with whom he enjoyed the "sweetest kinship" — was deteriorating.

She'd be first in the carpool line. Or feel sick when he was gone, like she wanted to throw up. When she'd tell other moms, they looked at her like she was nuts.

"I thought, I need to listen to that voice, because most people aren't experiencing that," Utley says. Since then, she has home-schooled all four of her children. She realized she was passing up a public education in Williamson County, regarded as the Cadillac of Tennessee school systems. But it felt right.

Nearly 1,300 families in Davidson County follow a similar path. They keep their children home, but not in isolation. Various parent and home-school community groups around the city gather children for joint weekly classes in Spanish or chemistry — subjects parents have trouble teaching. Others have regular meet-ups where parents trade notes while children play.

But if the kids need socialization and further instruction, why not attend MNPS? Reasons vary. While some parents point to the quality of local public schools, the factors are far more complex.

Some say it's important to be their child's teacher or to meet their special needs, whether it's Asperger syndrome or hatred of school uniforms. Some say they enjoy sharing a love of reading, of science, of intellectual growth with their kids — and it's a bonus that rock climbing can qualify for earning a gym credit. Others point to ambition — say, a daughter who's serious about ballet and needs the flexibility to practice.

The Utleys continued with home schooling even after they moved to Maryland for a few years. When they returned in 2013, however, Jack signaled a change. After nine years, he wanted to go to a public high school.

This time, she was ready to let him go. Jack, now 15, was zoned for Stratford High School, which has suffered over the years from a rough reputation. And yet his fascination with engineering made his transition easy, thanks to the school's growing emphasis on science and math.

Nevertheless, according to MNPS records, more than 400 kids zoned for Stratford this year decided to attend a different public school. Of those who opted elsewhere, about a third go to East Nashville Magnet School. Another third go to top-ranking Hume-Fogg High Academic Magnet and Martin Luther King Magnet School, while the others scatter across the district.

Because of that exodus — which has continued for years — 40 percent of Stratford's seats sit empty.

Her next oldest son, Charlie, now 13, decided that he wanted to try out public school as well. Because he was easily distracted by girls, however, they thought an all-boys school would suit him better. They chose a charter school in Madison, Boys Preparatory, which touted pillars of excellence, brotherhood and unity.

Stratford may have had the attrition problems and the worrisome reputation. But for the Utleys, Boys Prep was by far the worse experience. Boys there had major behavioral problems that teachers and staff were unequipped to handle. Leadership was nonexistent — when Utley would substitute-teach there, she'd have to break up fights. By year's end, Charlie was attending a funeral for a classmate who'd committed suicide.

"There was just so much violence. My son is the-glass-is-always-half-full, and we saw him crumbling," Utley says. They wanted to take him out, but he insisted he finish the year.

But worse was coming. Not only was Boys Prep's overall academic performance in the gutter, the school was fraudulently enrolling students and not meeting special education laws. MNPS decided to close the school. Eventually, it filed for bankruptcy.

Charlie didn't want to go back to home school, though. Once he got a taste of public school, there was no turning back.

"He kept saying, 'I want to feel the weight of responsibility,' " Utley says. "When he could articulate it that way, I thought, that is very valuable." It wasn't that her sons didn't have any responsibilities at home, she explains; they just wanted some independence.

"We're not raising boys, we're raising men," says Utley's husband Michael, who runs an Internet marketing company out of his home.

The next year, they moved Charlie to Litton Middle School, which she calls "night and day" compared to Boys Prep. They've decided to transition the rest of their boys there. Third in line, Harry, 11, will enroll next fall, leaving 8-year-old George as the last of her home-schooled boys to enroll the year after.

"I've been doing it for 10 years. I'm so burned out," Utley says. She's in the middle of a busy East Nashville community center that serves as an unofficial meeting place for home-schooling families. Dozens of moms sit trading notes and nibbling cookies while their kids — toddlers to teenagers — tackle the nearby playground.

"That's the biggest challenge. I'm just tired, but I know that this is what I'm supposed to do. I think that's life. There are hard things in life that we can't deflect from."

For some students, the struggle only starts with the choice.

Brandon Ramsey

During Brandon Ramsey's seventh-grade year, he racked up some 525 hours riding the bus. Not the school bus — a city bus.

He started the commute as a 12-year-old, spending about an hour-and-a-half rolling from Antioch to the downtown bus station before transferring to another line that would drop him off in front of West End Middle School. In the afternoon, he'd do it all again to get home.

As difficult as it was, his mother, Maribel Taveras, wishes he could have started sooner. The first time she tried to win him a sixth-grade seat in a school district lottery, she failed.

MNPS asks families every fall to consider their options for next school year. The district invites thousands of families and students to a "Choice Festival" where they can window-shop 85 choice schools the way you browse tables at a flea market.

This year, parents turned in some 46,000 applications of various kinds to change schools next year. With many schools attracting more children than they have seats for, final decisions are made via an electronic lottery closed to the public. The results will be available Jan. 9, with acceptance and waitlist letters mailed to parents Jan. 14. Last year, according to MNPS, 85 percent of students won their first, second or third choice.

But Maribel wasn't interested in a second or third choice. So she tried again the next year. This time she scored Ramsey a seat — and with it a 90-minute bus ride to and from school.

Ramsey was already a strong reader. He had a penchant for reading Maribel's old college science textbooks when he was in elementary school, even though his mom, an immigrant from the Dominican Republic, didn't have as much time to read to him as she did her two older girls.

But the fifth-grader was finding too much idle time at his desk at Apollo Middle School. He'd be the first to get his work done, and the first to mess around while other students were still scribbling. Brandon's teachers suggested that maybe he should go to a school that would challenge him more.

That meant securing a slot in West End Middle, which feeds into Hillsboro High School — the equivalent of making an opening chess move intended to pay off hours later. Although magnet schools Hume-Fogg and MLK rank annually among the top 100 schools in the country, Hillsboro High School is largely considered the next best option for students who don't win the lottery. The school's International Baccalaureate program is highly revered as a pathway to college.

"At first I didn't want to do it, just leaving the school where I thought my life was," Brandon says. "I thought I was going to, like, die without everyone. I was being a little dramatic.

"At the beginning, I didn't know why she wanted me at this new school. There were no perks to go going to the school itself, West End, other than I just got to feed into Hillsboro. Once I realized the opportunities that I'll be given in the next two years — and I didn't realize that until eighth grade — that's when I was like, 'Oh, all right, this is probably what's best.' "

Now a sophomore at Hillsboro, Brandon wants to be a surgeon some day — a field that includes a long line of schooling his family can't afford. Even so, he argues, he's got a better chance of getting a scholarship there than he would have if he'd stayed on the South Side, where his classmates lacked optimism about the future.

"Compared to everyone else, I was a saint, let me put it that way," he says.

Look across the city to the west, and you'll find an embarrassment of riches — rolling hills, million-dollar homes, beautiful front lawns and, statistically speaking, better schools in the Hillsboro and Hillwood High School clusters, according to the district's own statistics.

It's a desirable area to send children to school. But many families opt out of there, too, deciding that private school is a better answer.

Rick Perry, president of Goodpasture Christian School in Madison, sees the greatest student influx in fifth through ninth grade. While not all students choose to stay, the 7 percent attrition rate is typically for financial reasons. Tuition at Goodpasture, which serves about 900 students from at least six surrounding counties, runs a little more than $9,000 a year.

"I really believe, to a lot of people, the cost is what really makes them unnerved," Perry says.

And yet private school enrollment in Nashville runs well above the national average. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, around 9 percent of children across the U.S. will attend private schools this year. In Davidson County, that number approaches 10.5 percent.

Some parents grew up in private schools and want a similar experience for their boys and girls, whether at an elite private academy or at a theological school. They say the quality of education is higher and the standards are more rigorous — better preparation for college and life beyond. Advocates of neighborhood public schools charge that overprivileged families would rather send their children to schools where kids look more like them.

What cannot be argued is that private schools have enticed students away from their zoned schools in particular and Metro in general. Take the graduating class of 2018 zoned for J.T. Moore Middle School on Granny White Pike. As sixth-graders in 2011, the families of 148 children banded together to stick to their zoned school. Some 28 were already in private school, and 26 were scattered around the city.

By the next year, the number of classmates attending private school roughly doubled, to 57. Meanwhile, 14 students got into the elite Martin Luther King Magnet School and a few others also tried other options. The core class was down to 103.

By freshman year, nearly half of the original sixth-grade class was gone. Seventy-six were in private schools, and 25 had seats at the city's magnet schools. The rest spread elsewhere throughout the district.

Of the numerous parents the Scene contacted for this story, almost all declined to talk publicly about their decision to send their children to private school. Most said they were afraid of backlash, of hurting the feelings of neighbors or fellow parents who had chosen a different path. Some simply felt it wasn't anyone's business.

"They don't need to understand," one mother told the Scene. "We do."

One parent told the Scene they had counted on MLK as their kids' ticket to a quality education, and when they didn't win the lottery, they started exploring their options. Another liked their zoned school until they met the principal. For another, the turn-off was a teacher; for yet another, it was the school stating that students with a C or better need not bring their parent to teacher conferences. Even then, a few said the decision still left them feeling guilty.

"Making that choice has a sense of betrayal, too," one parent told the Scene. "A traitor feeling."

The private school boom largely began when Metro schools fell under court order to desegregate. In 1971, to hasten integration, the U.S. District Court directed MNPS to begin busing black inner-city students to schools outside their neighborhoods. By the early 1980s, the court pushed for busing citywide.

"Those kids went every which way," remembers Larry Collier, who ran the MNPS office of student assignment at the time. "There was no rhyme or reason or easy path."

Housing projects were divided in halves or thirds, he recalls. Some students were zoned to five different schools in their school career. Even if the constant change hampered student achievement, Collier says, the district simply didn't have a choice.

In that time, according to MNPS records, the school system lost nearly a third of its students. Student enrollment was 96,000 in 1971. By 1985, it had plummeted to 65,000. The district hit upon magnet schools as a way to restore balance.

By 1998, the court was satisfied with the city's desegregation. It ended mandatory busing across the city and gave Nashville a "unitary status." Yet it took another 10 years before MNPS could settle on a student assignment plan that eliminated disjointed school zones and adopted better transportation options.

Examine the city's schools today, and some look anything but diverse. Not even half the county's public schools meet the MNPS definition of diversity, which includes race, ethnicity, income, language and disability. Among Metro's 157 schools, 14 are more than 90 percent black, some reaching 100 percent.

And that's still an improvement from 17 schools two years before.

"You still see that to a certain extent today where we have schools not as diverse as they could be just because of the housing patterns," says MNPS spokesman Bass. For a long time, he says, "only people with means really had any choice at all."

On average, 7,680 students leave the district each year, according to a 2013 study by Vanderbilt University's Peabody College Department of Leadership Policy and Organizations. The study, which examined MNPS data from 2008 to 2012, found that departures — whether to private schools or out of the county — amount to a MNPS attrition rate of 9.6 percent annually.

Worse, while student enrollment in Davidson County was nearly flat from 2000 to 2011, the study found that student enrollment in surrounding counties was booming. Williamson County's grew by 41.6 percent. Rutherford County's grew by 40.5 percent. Davidson's, in comparison, paled — at 1.5 percent.

The student population leaving MNPS is disproportionately white, according to the study. Breaking up the district's composition into percentages, 11.7 percent more white students are leaving the district than are represented in Metro. Meanwhile, 9.9 percent fewer black students are leaving compared to their representation in MNPS. According to state records, while the city is about 60 percent white, the school system is 45 percent black, 31 percent white, 20 percent Hispanic and 4 percent Asian.

Today the state recognizes 70 private schools in Davidson County, with the highest enrollments including Christ Presbyterian Academy, Family Christian Academy, Lipscomb Academy and the University School of Nashville — all K-12 schools with considerably more than 1,000 students each. Others have enrollment of only double digits, teaching either a class or two of kindergarten, a handful of elementary school children or a few dozen in high school. Only parents will know which best suits their child, Goodpasture's Perry says.

"I'd encourage parents to just, don't feel like you're sort of handcuffed," he says. "Go explore those things. Find the school that will help your child [that] really encourages them to dream and to think that they can be more than they think they can."

Titus Gore

Briley Parkway never looked as calm and peaceful as it does at night right before turning the corner downhill to Titus Gore's house in North Nashville. Titus is just as serene, a soft-spoken but earnest 11-year-old in his first year at a charter school.

The adjustment was tough at first. His school, like many charters, focuses on discipline. Teachers would give him "demerits" if he made an unnecessary or improper noise, or needed more than two emergency bathroom breaks in class. He had to learn to sit up straight, with his hands clasped in front of him, and follow all the rules.

He doesn't mind those restrictions now. He says he's happier at Nashville Academy of Computer Science than he was at Tom Joy Elementary. Kids would act out there, he says, and teachers weren't always in control.

"It wasn't the best school," he says, then quickly adds, "I'm not saying that because it's a public school."

Divisions have been drawn deep in the sand in Nashville over charter schools. In political and education circles, you're either labeled as "pro" or "anti" charter, with little room for anyone to stand in the middle.

The rallying cry for charter school advocates is that many Metro schools are underperforming, particularly in areas with high concentrations of poor, black children. They say charter schools, which are funded with public-school dollars but run by private groups with their own standards and philosophies, can give parents an alternative to their zoned school. Several offer a bridge over one of the greatest hurdles to school choice — transportation.

And people are choosing them. This year, 5,919 students will attend charter schools, with many serving the North, East and South sides. The growth is expected to continue, from 7 percent of MNPS students today to nearly 10 percent by 2016. Nationwide, all but eight states have laws permitting charter schools, with an average of 4.6 percent of public school students attending one. At some 150 school districts across the country, charter schools account for more than one in 10 students.

Toshiba Danielle Gore knew she wanted a change for her son. A graduate herself of Hunter's Lane High School, class of 2002, she wasn't crazy about the public school system. She didn't go on to college after high school because she had already landed a job at Comdata, where she works to this day.

Like 11 percent of families across the district, she started to consider change as Titus was entering middle school. Without the money for private school, she listened when a co-worker recommended Nashville Prep. After a tour, she planned to send Titus there — until she heard about the Nashville Academy of Computer Science, where the curriculum would teach kids coding. Sold.

The school is one of the first in the country to focus on computer coding. As a sixth-grader, Titus is learning how to write programs for games, like one with a shark chasing a starfish.

"The coding, that's it. It's a new school, which I didn't know what to expect," Gore says. "I just knew anything would be better than Metro."

She's not entirely pleased with the school's emphasis on discipline, but she says it makes sense. She says her 8-year-old daughter Cequoyah, who lives with her dad, could benefit from that kind of structure, though she jokes her little girl would probably be snowed under with demerits for sighing all the time. Starting her in elementary school might be good practice for the structure of a charter middle school, she says.

And for her youngest, 3-year-old Malachi, she's eyeing Nashville Classical for kindergarten.

"I just tell them to study hard so they have choices," Gore says, stirring taco meat in a skillet on the stove. "I don't have choices. You need a career or to be your own boss. Keep yourself open. I'm scared to try new things because I know what I do works."

Titus doesn't know what he wants to do when he grows up. He knows he likes math, and he likes coding, he says, but maybe he'll like something else someday. As he talks, he pulls up his latest project in coding class.

It's a maze. Brick by brick, he's stretched rectangles across the screen to build walls and erect roadblocks. Around the corner are some cheerful-looking icons that rack up points. A candlelit cake sits the end of the maze — a reward for finding the correct path.

But down in the corner is a multicolored ball that's almost impossible to reach. It gleams like the pot of gold at the rainbow's end. It's a grail that keeps a player weaving carefully through jagged edges without touching the wall. A player accepts this struggle up until the moment he captures the ball — at which point he learns, after all that effort, it only ends up taking points away.

Email editor@nashvillescene.com