Chris Gantry's smartphone rings as often as a 17-year-old's, and he sends text messages with notable regularity. And he dresses sharp. Today it's a sharkskin coat, jeans, a black T-shirt, an inch-tall silver cross on a long chain, and sleek canvas shoes. The jaunty chapeau he carries is conditionally optional. He is slender, but not lanky, and his goatee is Kenny Rogers white.

His forehead may have expanded northward just a bit, but his hair is otherwise impressively thick. It's not hard to imagine it going full-bore Einstein, should the wind catch it just right. His hands are the only part of him that look his age, an illusion that evaporates when he picks up his guitar. And she's a beaut — a 1955 Martin D28 flat-top with ornate pearl inlays where the insignia once was.

Perhaps his guitar is a fountain of youth; his hands shed years when he plays. His fingers pluck and dance with artful precision, something he's been doing for a long, long time. When he sings, as when he talks, his strong voice has a gravelly edge.

And if he thinks you are one of country music's enemies — the yes men, carpetbaggers and ass-kissers; the tramplers of tradition and the empty hats with accessorized accents; the hacks who grind Hank Williams under their SUV treads chasing the trend of the moment — he will cut you with it.

"You stand up there on 16th Avenue and it's as dead as Kelsey's nuts," Gantry says. "It's the deadest piece of shit on this planet. The Gaylords took a good and pure thing and turned it into a concessions stand of country music. That street should be like the French Quarter in New Orleans. There should be celebrations in the streets with music coming out of all of those houses. They should get rid of that statue at the end of the street and put up a statue of the Highwaymen.

"This place seems to want to decimate that."

If he sometimes sounds like an ornery gunslinger itching to draw, he's entitled. Chris Gantry is an O.G. Nashville troublemaker, an outlaw before the term was adopted as a marketing handle. He's a singer-songwriter by trade, a beat poet and raconteur at heart, and a playwright much of the rest of the time. He is as nostalgic as the rest of us for days gone by — specifically the days 50 years ago when he rolled up on a Music City entering an era of bohemian craziness, groundbreaking songcraft and unparalleled creative freedom.

But generally, he focuses on the future. On this spring, when he and 16 others will be inducted as inaugural members of the forthcoming Outlaw Music Hall of Fame, scheduled to open this year in Lynchburg. On the day Kris Kristofferson, his friend of 50 years and songwriting contemporary, visits Nashville. On the day his second children's book gets published, and on signings for the freewheeling memoir he published just last year — and on gigs he has yet to book.

Still to come, off in the distance, is what he's really waiting for: the day enlightened songwriters, true-to-self performers, and industry executives with a bold new vision drive steamrollers over the contemporary country music industry, and raise some hell in this Disney park of a town strutting around these days with a swelled head.

"These new guys just pretend to be country; it's a joke," Gantry says. "They're not country, and what they write and sing is not country music. I don't know if there's a thing such as country music anymore."

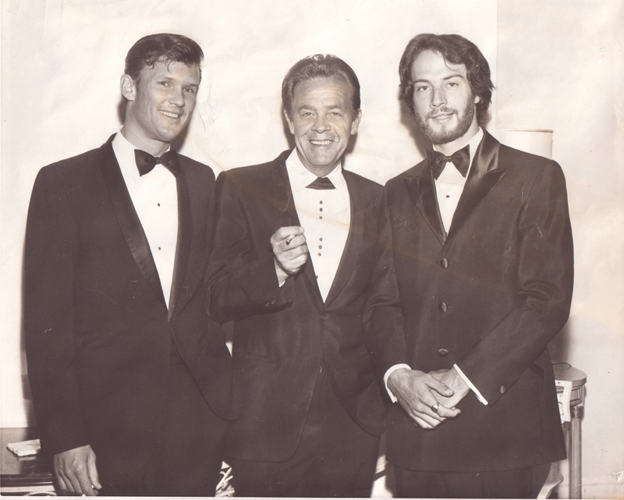

Gantry should know. He's has been active in Nashville's music industry longer than most, penning more than 1,000 songs to date and performing at dive bars and the Ryman alike. Heavy hitters including Johnny Cash, Glen Campbell, Reba McEntire and Roy Clark have recorded 70 or more of his songs. He and Kristofferson were buds before the Grammy-winning/Oscar-nominated latter co-wrote "Me and Bobby McGee" with Fred Foster. ("It was originally going to be 'Bobby McKey,' but Kris changed it," Gantry says.)

He inspired one of Kristofferson's finest songs, "The Pilgrim: Chapter 33," in which the singer name-checks him in the intro. He crashed Woodstock by helicopter and joined folksinger Tim Hardin onstage — not only unannounced, but uninvited — in singing the anti-war anthem "Simple Song of Freedom." And he and Shel Silverstein hung out for years, long before the sidewalk ended.

If country were to stand trial for phoning it in, Gantry would gladly be judge and jury. He might excuse a few modern-day performers from the proceedings — interestingly, he's really fond of Taylor Swift — but he'd pretty much throw the book at the rest.

Nevertheless, one cold afternoon before Christmas, accompanied by a reporter and photographer, Gantry took a walk through the Nashville he knew, revisiting old haunts from the days newcomers shook the industry by its wide lapels. He started out where he started out — downtown Music City, where tourists come from all over the world to get a facsimile of the honkytonk life.

He could show 'em a thing or two.

Noon, December, behind the Ryman Auditorium. A newly hung neon sign outside the back door of Tootsie's Orchid Lounge claims the alley as its own — something disputed by a cast-iron 85-pound manhole cover nearby, which declares the ribbon of asphalt connecting Fifth and Fourth avenues to be "Historic Ryman Alley, Music City."

"Tootsie's back room was different back then," Chris Gantry says. "There was no bar. If you were a serious songwriter, this was the Garden of Eden."

But that's as sentimental as Gantry gets about these hallowed spaces. Though his presence on Lower Broad turns heads — as anyone's does downtown, if a camera and notepad are present — he might as well be checking in at the office. He's been here a thousand times and moved on. He's more excited about slipping into a booth close to home at the International Market on Belmont, the Thai cafe that's been feeding hungry musicians since the 1970s.

Before Lower Broad became a tourist magnet, before the Grand Ole Opry moved across the river, before Willie sang about blue eyes cryin' in the rain, Chris Gantry was a kid in Queens, N.Y. Unhappy at military school, he learned to play his guitar along with Louvin Brothers and Bill Anderson songs he heard on the radio, and taught himself to write songs like those Bob Dylan would eventually debut in Greenwich Village — meaningful and deep.

Gantry showcased his talents at local gigs as a high-schooler. Soon, he and a classmate had a short-lived record deal. They recorded as an act under the name "Tom and Jerry," which a young folk act consisting of Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel had recently abandoned upon the advice of their handlers.

Barely 21, Gantry arrived in Nashville battered and bruised at the hands of his father. The two exchanged blows for "several minutes" over the path the younger Gantry's life should take. It was a fight of love, he would later say — his father's attempt to dispel the dream that lured Hank, Patsy, Faron and thousands of others to Music City and potential destruction.

"Sometimes we have to fight for our freedom," Gantry writes in his 2013 book Gypsy Dreamers in the Alley, a 270-page compilation of his anecdote-studded, stream-of-consciousness Facebook posts and thoughts on songwriting. He notes that he and his father later patched things up.

When Gantry arrived in 1963, Porter Wagoner and his outrageous stagewear were in full flower, a baritone Man in Black was booming out "Ring of Fire," and Flatt and Scruggs struck black gold of their own with the sing-along-friendly theme to The Beverly Hillbillies. The mid-1960s Nashville he describes in Gypsy Dreamers was "this warm wanton seductive woman, seducing you with tender rage and blistering encounters." It was a place where he might find the pioneering African-American Opry star Deford Bailey running a barbershop on Eighth Avenue, then hang out with him after hours with a band of fellow musicians, high on homemade beer as Bailey's harp conjured up a night train. It was where he found lodging in a rented house near the Belle Meade Mansion for $50 a month, stepping every weekend over his passed-out married-lawyer landlords and their liquor bottles.

He planted his own Music City roots first in Skull's Rainbow Room, the burlesque bar in Printers Alley run by the colorful impresario Skull Schulman, who was murdered there in 1998. There he met Kris Kristofferson, who had yet to make a name for himself. The pair pulled shifts at Skull's, strumming and singing while Vegas-style showgirls reapplied spirit gum to their pasties offstage.

"Skull was very good to me, like he was to all the musicians who played there," Gantry says. "I met a lot of people in Skull's Rainbow Room. That's where I got my start in Nashville."

It was in these years — and in these kinds of watering holes — that the seeds of the Outlaw movement were sown, a decade before Waylon and Willie and the boys carried Outlaw Country to the top of the charts. Dylan recording in Nashville only challenged the likes of Kristofferson, Gantry, Silverstein and many others to push the bounds of orderly Music Row songcraft, allowing a new frankness (along with hints of psychedelia and personal mythology) into their lyrics. They pushed aside the embroidered stage suits and coiffed pompadours in favor of shaggy hair, open collars and tight jeans.

This new generation came of age in the shadows of the day's Opry stars, figures like David "Stringbean" Akeman, Roy Acuff, Webb Pierce, Flatt and Scruggs, George Jones, Chet Atkins and Lefty Frizzell. They spent their Friday and Saturday nights in Tootsie's back room and in the alley between the now-famous honky-tonk and the legendary Ryman. They used the locales as informal staging areas before, during and after their appearances at WSM's twice-weekly Grand Ole Opry broadcast.

Before his own first appearance at the Ryman, Gantry used to hang around waiting to slip through the backstage door, carrying his guitar to blend in with Faron Young, Bill Monroe or the Glaser Brothers.

"I don't know how many times I snuck into that door right there," he says, pointing to an alley-facing portal near Fifth Avenue. Once inside, Gantry recalls, he mingled. He says the established performers didn't mind, emphasizing that "things were just different back then."

"I watched Bill Monroe and Flatt and Scruggs trade licks before going onstage. Holy God, it was unreal," he says. "I opened up my guitar case and joined in when I could. They didn't seem to mind."

Gantry wrote songs with Kristofferson and Silverstein from time to time. For the most part, though, he wrote by himself.

"That's just the way it was back then," he says. "Today songwriters are terrified to be alone with their thoughts. They huddle together and keep writing the same song over and over."

Gantry describes songwriting as a "divine experience" in the introduction of Gypsy Dreamers in the Alley. Kristofferson and Dolly Parton each wrote introductory remarks for the book, which is part how-to guide to songwriting, part fist-shaking rant against the state of country music, and part salute to yesteryear, when he and scores of other up-and-comers such as Billy Joe Shaver, Loretta Lynn and Merle Haggard redefined how songwriters and performers plied their trades.

"I had an epiphany at a very young age," Gantry writes, "that songwriting is a Godly gift, and if rightly viewed as something He did instead of something I did, the two of us could form a co-writing partnership as long as I let Him be the captain of the ship and I the first mate."

The paperback is sometimes dreamy and whimsical, sometimes blunt, and persistently steadfast to the notion that inspiration is a divine gift not to be trifled with. The world's best songwriters, according to Gantry, know not to tinker with lyrics or melodies whispered into their ears by angels.

"That only messes it up," Gantry says. "What if John Hartford had rewritten the first line to 'Gentle on My Mind'?"

Recognizing inspiration, and respecting "that you're only the conduit," is what separates shallow songs from meaningful ones with lyrics that pry open the human condition.

" 'Gentle on My Mind' could have been written by Shakespeare," Gantry says. "An angel sat down on John's shoulder the day he wrote it. It was the same as when Kris wrote 'To Beat the Devil,' 'Vietnam Blues' and 'Sunday Morning Coming Down.' This was divine poetry that spoke to deep truths about our humanity."

In his book, Gantry explains to aspiring songwriters that developing their craft includes tackling themes that are universally meaningful. He doesn't say a damn thing about pickup trucks, river banks, or drinking moonshine/whiskey/beer with your bros on a Saturday night.

"To me, the first line of the song should be as close of a transcription to whatever it was the angel delivered to you at that first moment of heightened inspiration," Gantry says. "It's the idea that you're in the 'music business' that screws everything up. Take care of the song and the rest will take care of itself."

One song has taken care of Gantry over the years — the biggest hit of his songwriting career, and a song frequently cited when people describe the changes that swept country music in the late 1960s and early '70s. It's "Dreams of the Everyday Housewife," a wistful ballad that Glen Campbell took to No. 3 on the country charts in 1968.

A stirring reverie in which a husband senses the past loves and carefree youth his wife silently mourns — "The photograph album she takes from the closet and slowly turns the page / And carefully picks up the crumbling flower, the first one he gave her now withered with age" — it struck a chord with young American women growing restless trying to fill the dinner's-on-the-table mold of June Cleaver.

"The Outlaws wrote about deep emotional twists that occur in people's lives," Gantry says. "That's what we did. You hear it in 'Dreams of the Everyday Housewife.' We wrote about the torment of lust, and the celebration of love. We wrote about life in a way that hadn't been done in pop culture before."

Gantry also put out four albums of his own, including the acclaimed 1970 release Motor Mouth, which includes another of his signature songs, "Allegheny." His YouTube-searchable performance at the Ryman, recorded for Johnny Cash's television show, shows him seeking the same depths Dylan was exploring at the time in his evolution as a one-man wrecking ball battering social norms and musical trends. Johnny Cash would later record "Allegheny" himself, strumming rather than fingerpicking Gantry's complex arrangement.

By the late '70s, however, Gantry sensed the mood in Nashville shifting. In the 1980s, he traded the grind of being a cog in the Music Row machine for Key West, Fla. — always sun-drenched, always boasting a cool coastal breeze.

"I loved it down there," he says. "I played music in dive bars, and just enjoyed myself."

One day, in just such a place, he heard a familiar laugh coming from the back room. It was his songwriting pal Shel Silverstein, who unbeknownst to Gantry, had been living the Caribbean dream long before he had the same idea. Among his many creative outlets — poet, cartoonist, children's book author, not to mention an accomplished songwriter who struck gold with Johnny Cash's "A Boy Named Sue" — Silverstein also wrote more than 100 plays, as well as a screenplay with his close friend David Mamet.

"I asked him how to do it," Gantry says. "I asked him to show me how to write one-act plays."

Silverstein's lesson lasted exactly one hour. He told Gantry to write dialogue between a man and a woman for 60 minutes straight, using "M" and "W" to identify who's speaking.

"He said not to take my pen off the paper for 60 full minutes," Gantry says. "Just keep writing. And that's what I did." Gantry went on to win the Tennessee Williams Playwriting Contest with a collection of one-act plays titled Teeth and Nails.

Today, Gantry writes songs for Cool Vibe Music Group and its president James Aylward, who also published Gypsy Dreamers in the Alley. Gantry also mentors young artists who are, for now, undiscovered, and he envisions ways to address other faults he finds with the latter-day Music Row.

"That street from Belmont University to that godawful statue should be a nonstop year-round celebration, with vendors, food, jugglers, dancers and parades," Gantry says, leaning forward in his booth at the International Market, fist clenched for emphasis. He sees Nashville as the Crescent City, and Music Row as its French Quarter — an emblem of the city's history, its colorful characters and upheld traditions, as well as a place for creative talents of all stripes to congregate.

But first, he insists, we've got to get rid of Musica. To much of the city, the nine nude figures dancing in the Music Row Roundabout's bronze centerpiece represent the Row's outstretched offering to the rest of the city and its visitors: the gift of music. To Gentry, it's a needless abstraction of the titans who hoisted Music City on their shoulders, as off-putting as the striated texture of the figures' skin — a remnant of its original intent as a fountain.

"Tear it down and install a sculpture to honor the Highwaymen," Gantry says, referring to the supergroup formed by Kristofferson, Cash, Waylon and Willie — all fellow charter members of the firebrand Outlaw country movement. "After that, we can talk about where to put a country music Mount Rushmore."

Email editor@nashvillescene.com.