Editor's note: In March, the University of Chicago Press will publish Making the Unequal Metropolis: School Desegregation and Its Limits, a history of the desegregation era in Nashville by Columbia University Teachers College assistant professor Ansley T. Erickson. A former Nashvillian, Erickson returned to spend three summers here researching her book and conducting interviews with locals, and in this piece she discusses the striking similarities she sees between the Nashville of four decades ago and the city today.

Soon, perhaps within months, Nashville will have a new generation of education leaders. The city will choose a mayor, and once it resumes the halting search that failed earlier this summer, the school system will find a new director. What kind of leadership the city needs, how it measures its challenges and its opportunities, how it defines and pursues (or dodges) equality — these are pressing questions.

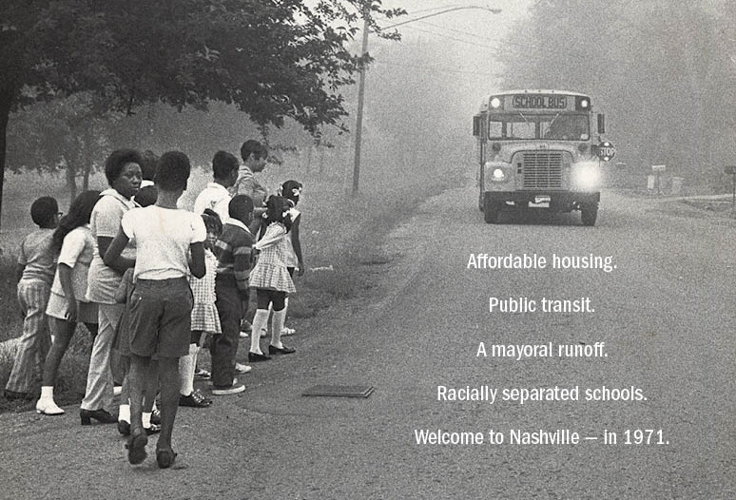

Yet the same questions were just as pressing four decades ago. The year was 1971, not 2015. But then as now, another mayoral runoff dominated the dog days of another hot summer. Then as now, the city's central concern was much the same: education.

Incumbent Mayor Beverly Briley and insurgent Metro Councilman Casey Jenkins competed to see who could most vociferously oppose a controversial new development in Nashville schools — desegregation through busing. For the first time, most Nashville schools would no longer serve nearly all-white or all-black student populations. (The district then had very few students of Latino or Asian descent). Instead, students would ride buses out of their neighborhoods to help achieve court-specified racial ratios.

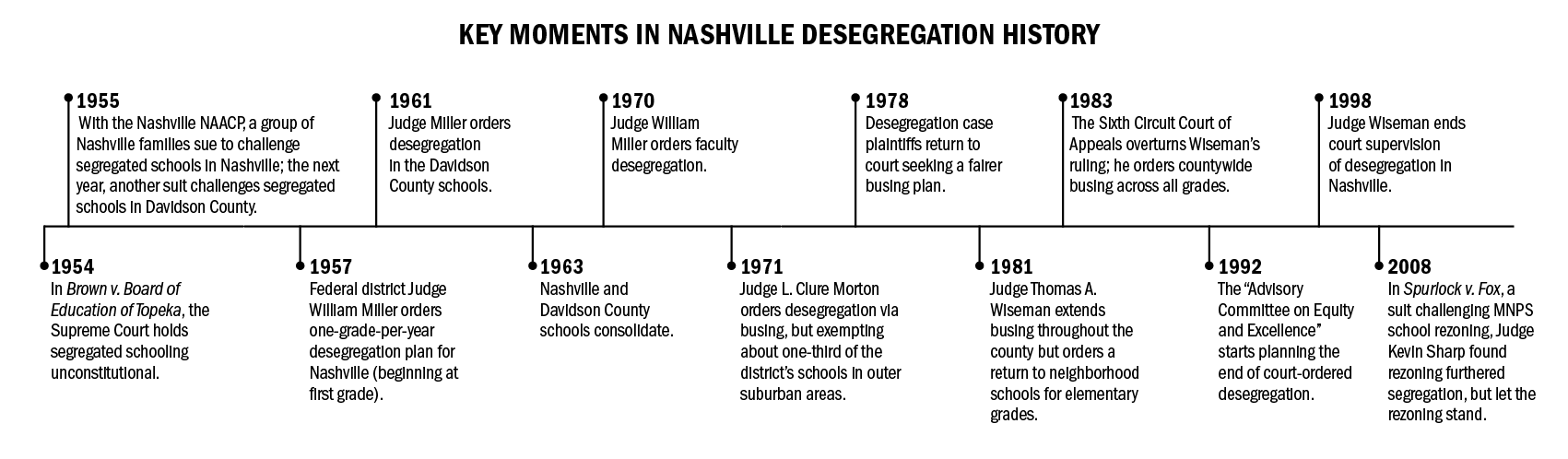

They did so from the fall of 1971, under plans that shifted a few times, until 1998. In many respects, busing for desegregation was the big education story of Nashville's 20th century. Much was different then than now.

But with startling prescience, the 1971 election, and the story of Nashville's schools in the years since, foreshadows today's debates on education and the city's future. So many of the issues that currently concern Nashville — access to housing, the impact of race and class divides, the best path for public schooling — surfaced in that sweltering summer four decades ago. Others that are newer, like gentrification, had important precursors then.

At this crucial juncture for Nashville and its children, a look to the past might help.

Missed Opportunities

From reading newspaper accounts in Nashville's two dailies of the period, it's clear that candidates Briley and Jenkins saw busing not as an opportunity, but an intrusion. Desegregation threatened cherished realms of family authority and property rights, they felt. Like many white Nashvillians opposed to busing, they thought those extended beyond the home to the local school.

Jenkins organized rallies that interrupted court proceedings. Once busing was ordered, he preached outright defiance. Busing became his campaign's sole issue. Fifteen thousand came to his rally at the State Fairgrounds speedway, roaring their assent as Jenkins decried breaking down the schools' racial separation as "communism" "creeping in to the city." He promised to delay or close school.

That was beyond his authority, but no one minded. "We want Casey!" the huge crowd stomped and chanted.

Briley spoke in more measured tones. Privately, according to Nashville Banner reporter Dick Battle, he was uncertain what his stance on busing should be. Publicly, his disdain rang loud and clear. When constituents wrote to him, he replied that Nashville's busing order was the "worst" in the nation. He did "not believe that the school is a social experiment," as if segregation itself were not just such a thing.

Neither Jenkins nor Briley said it directly, but both succeeded in assuring white constituents that the privilege they had long enjoyed in Nashville's schools, often at clear costs to their black peers, would continue. On the topic of what made busing's drastic measures necessary, Briley and Jenkins said nothing, as did many other local opponents.

But Kelly Miller Smith, longtime civil rights leader, Nashville parent and pastor of First Baptist Church Capitol Hill, presented the case succinctly in an archived letter. Busing was an effort "at remedying the glaring inequities in public education as far as black young people are concerned," Smith noted. "The problem is not busing. ... Rather, the problem is racism. ... We see busing as a significant and effective effort at dealing with the real problem."

The "real problem" was not hard to see. In 1970, before busing began, 43 of Nashville's 140 schools operated with 99 percent or more white students; 86 had fewer than 10 percent black students. At the other extreme, 21 schools served 90 percent or more black students. Sixteen years after Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the 1954 case that deemed segregated schools unconstitutional, the vast majority of Nashville's students, black or white, essentially attended schools sorted by race.

Inequality aligned with segregation. Thousands of black students in Nashville attended schools that were visible threats to their health and safety. These firetraps, described in a 1970 MNPS study as having insufficient plumbing and crumbling ceilings, all but embodied the concept of separate but unequal. Black teachers used their own dollars to cover funding gaps not present in largely white schools.

Gaps in achievement were just as wide. Before busing, 71 percent of black Nashville elementary students scored below the national average in math, as opposed to only 30 percent of white elementary students. Reading scores showed black students dramatically behind as well. If those students could have access to the superior facilities and resources often found in white schools, Nashville desegregation advocates hoped to end their long-standing lags in performance and opportunity.

And long-standing they were, having malingered past an earlier phase of desegregation in Nashville. After the Supreme Court's Brown decision in 1954, black community leaders sued for desegregation locally. The board of education designed a token gradual plan. With tremendous courage, 19 black first-graders enrolled at segregated white elementary schools in September 1957.

The 6-year-olds arrived to face white adults brandishing Ku Klux Klan signs and Confederate flags. Bystanders glowered at small children on their way to school. A nighttime bombing rocked an empty school building in East Nashville. But calm soon returned — and with it the resumption of scholastic racial separatism, for all but a tiny proportion of Nashville's students.

The broader assault on that racial barrier began in 1971. By then, neither Jenkins' nor Briley's rhetoric could stop the buses from rolling. Casey Jenkins lost the election, but kept up a few months of pickets and protests before leaving town. Briley found quieter but more powerful channels of resistance. After winning his second term, he pressed federal Judge L. Clure Morton off the case, setting in motion years of minimal judicial engagement with busing. Meanwhile, leaders on the Metro Council restricted funds for buses, worsening logistical challenges.

Nashville had a rare set of opportunities in desegregation. Many other metropolitan areas had school district boundaries that separated the majority-black city from the majority-white suburbs. The Metro Nashville system enfolded the entire county. Combining busing with the scale and diversity of the metropolitan population, Nashville became one of the most statistically desegregated school systems in the country.

Busing was neither popular nor perfect. But it had significant positive educational and social outcomes for Nashville students, as in many other desegregating districts around the country. In terms of test scores, the data is limited. But a 1992 report compiled by then-director Charles Frazier indicated that average scores for Nashville's white and black students rose substantially, while reading and math achievement gaps had closed by between 25 and 40 percent in busing's two decades.

Nonetheless, Nashville lacked a strong voice in elected leadership standing up for desegregation's benefits. It didn't have to be this way. Charlotte's leaders embraced busing and desegregation as part of the formula for their city's growth. Later, Raleigh and Louisville created long-standing coalitions in favor of desegregating their schools.

Nor was opposing busing the only available option. Naming equality and fairness as civic goals helped other cities approach the task with less rancor and build more enduring public support. Nashville is a different place today than in 1971, or in 1998 when the federal courts ended their oversight of Nashville's desegregation. The school system now reflects the tremendous ethnic, cultural and linguistic diversity of today's city.

Yet segregation is far from over in Nashville's schools. According to the MNPS Diversity Report 2014-15, almost 6,000 black children in Nashville attend schools that for all practical purposes are segregated by both race and class, with more than 90 percent black children, and more than 90 percent poor children. (Both charter and district schools contribute to this figure.) In addition to missed opportunities for social learning and the making of informed citizens, these figures help produce Nashville's still-troubling gaps in achievement. Although unmentioned in the recent RESET Nashville report, the district's white students have markedly higher chances than black students of meeting proficiency standards, while black students are significantly more likely to score well below.

Nashville has opportunities today that are now unavailable to many American cities. In St. Louis and Baltimore, where dire segregation and injustice have been on ample and tragic recent display, fragmented city and suburban jurisdictions reinforce division and inequality. These districts may not have enough social or economic diversity to meaningfully desegregate themselves. But with its large metropolitan district and diverse population, Nashville could choose to act against racial and economic barriers — if the city's next generation of education leaders recognizes the problem and acts on it.

Housing policy is school policy is housing policy

In 1972, Dr. Sammie Lucas and his wife hoped to buy a new home. They looked near McGavock School, and liked a house for sale a few miles up the road on McGavock Pike in Donelson. It was owned by the Travis family. Upon visiting the home with the seller's real estate agent, the Lucases decided to make an offer.

But the Travises weren't interested in going to contract. They claimed they had a "color clause" on their property — a restrictive covenant on the deed, barring sale to a black family like the Lucases. They said they worried about how their neighbors, white like themselves, would react to a "Negro" family. The Travises didn't want to help further integrate the school, either.

The real estate agent told the sellers, rightly, that whatever "color clause" they had on their deed had been "outlawed." The Supreme Court ruled restrictive covenants unenforceable in 1948. The dispute came to a settlement out of court, and the Lucases found another home nearby.

The Lucases' story hints at the many roots of segregated housing in Nashville. Private actions — like sellers refusing to sell, or real estate agents refusing to show properties — helped keep most Nashville suburbs segregated and white for decades. But as hurtful as these individual actions must have been to families like the Lucases, they were small-bore compared to the federal policies that helped construct the segregated white subdivisions around McGavock in the first place.

White residents could make their postwar exodus to the suburbs, in large part, because of federal home-financing arrangements that weren't available to black neighborhoods and black borrowers. Major federal investments in highway construction made the suburbs more accessible; low tax rates on gasoline eased travel costs as well. As the segregated white suburbs boomed, public housing construction targeted city neighborhoods exclusively, helping to make "urban" seem synonymous with "black."

But the Travises' remarks were telling in another way. They wanted to keep their neighborhood white because that would keep their local school white too. The Travises were far from alone in linking all-white neighborhoods and hopes for an all-white school. Local officials had for decades thought of and built segregated schools and segregated housing together.

In 1959, Irving Hand and his colleagues on the Planning Commission mapped Nashville's neighborhoods into "planning units." That process required them to define what they meant by a neighborhood. For Hand, a neighborhood had key features — "similar ethnic groups," "population in similar income range" — and local elementary schools were central.

Hand wasn't inventing these ideas. He was borrowing them from nationally influential city planners who had started down this path at the turn of the 20th century. If Hand wanted to link neighborhoods of "similar ethnic groups" and schools, federal urban renewal projects led by his colleagues at the Nashville Housing Authority (the predecessor to the MDHA) provided one opportunity.

Inside their Edgehill urban renewal project, NHA officials figured out how to leverage needed expansions at segregated local schools to generate more funding for segregated local public housing. To maximize the funds, schools had to serve only those who lived in an urban renewal area. For private developers, the school board helped in linking new schools and new housing as well. This cemented the links between segregated housing and schooling. In essence, it formed a circle that kept students corralled by race and income.

Segregation in housing and schooling together had many historic allies in Nashville. The power of those forces dwarfed even an ambitious effort like busing. They still leave their mark on the city — not only in visible patterns of residential segregation, but in contributing to the wide gap in family wealth between white families (who built equity and saw properties appreciate) and black families locked out of this aspect of generational accumulation.

We might say Nashville has a robust history of exclusionary zoning, broadly construed. Today, the city has the opportunity to move to inclusionary zoning, which incorporates lower-income housing into the development process. There are many arguments in favor: breaking up clusters of poverty; encouraging cultural and economic mobility; bringing residents out of social isolation into the bloodstream of the city.

But recent research suggests Nashvillians should think about inclusionary housing zoning as school policy as well. Inclusionary zoning that allows poor families in Nashville to access more upwardly mobile areas can also bring children into more economically and racially diverse school zones. Inclusionary housing policies in Montgomery County, Md., and in Chicago show marked improvement in students' educational and life chances. After decades of yoking housing and schools together to create ruts of reinforced poverty and racial separation, rapid growth gives Nashville a chance to break its lockstep.

Who matters more?

There was nothing easy about busing. It deliberately disrupted neighborhoods and forced students out of their literal comfort zones. At the start of school each year, nervous parents guided cherished youngsters onto school buses to distant and sometimes unfamiliar parts of Nashville. Former school board member Kathy Nevill remembered one child arriving at a suburban school. The child's mother, living miles away, had been unable to introduce him to his new teacher in person. So she sent him on the bus with a note pinned to his shirt. Hoping to convey her love and care, she wrote, "My name is ... and my mother's name is ... and I live at ... "

In other parts of the county, adolescents had grown up wanting to cheer for their local school sports team or to play in the band at Litton High School. They planned to walk school corridors at Joelton where pictures of their grandparents lined the walls. They resisted adjusting to high school in a new setting. To be sure, busing was hard on black students and white students alike.

But it was harder for black Nashville children and families. Statistical desegregation did not mean equal concern for the educational experiences of all children. From travel burdens to school closures, local and federal officials designed desegregation to appease white middle-class families as much as they could. It was a black child who wore that note on the first day of school, because the district bused black 6-, 7-, 8-, and 9-year-olds out of their neighborhoods for desegregation. White children that age stayed close to home.

Sometimes, it seemed that black youngsters were nearly invisible. Most of the local press coverage of the start of busing in 1971 obsessed over white resistance, pickets and boycotts. Equally important — yet less reported — was the story that unfolded beneath the press's notice in the first days of school.

After months of detailed tallying of where Nashville's students lived, and how they would be zoned to meet court-ordered racial ratios at each school, principals, teachers and central-office officials prepared to greet their newly diverse student bodies. When the day came, they were stunned to discover just how many black students were arriving for school at McCann or Richland elementaries, at Cockrill and Charlotte Park and others. Hundreds more black students arrived than expected.

In retrospect, their arrival shouldn't have been a surprise. But long-running patterns in city planning had systematically failed to take black communities, families and children into account. Planners mapped Nashville into areas of "growth" or "decline." Black children living in public housing complexes, formally segregated until a few years before busing began, were swept under the label of "decline." Their city couldn't see them.

Once these youngsters were rediscovered, Metro Schools district officials walked the streets of Nashville's housing complexes, trying to make a better count and rezone accordingly. For the children, that meant a shift to another new school, another new route and routine.

Black communities also faced many more school closures than white communities. In the fall of 1971, six schools in or near North and South Nashville neighborhoods closed. Pearl, Elliott, Jones, Clemons, Howard and Central were either historically segregated black schools or had rapidly growing black populations. One (failed) proposal from federal officials was even more dire: to close all schools in the district's urban areas. These institutions had long been hubs of social networks and employment in black communities.

Facing another proposed school closure in the late 1970s, longtime educator Newton Holiday described North Nashville residents as "a group of people who suddenly find that everything that was once of great importance to them has gradually been eroded." For a leading group of black clergy, another school closing would be the "coup de grâce" for the community.

Busing compounded an already established pattern of disinvestment — some might call it an economic kneecapping — in Nashville's black urban spaces. Two previous decades of urban renewal projects and highway construction had sliced through front yards and cut off retail districts, forced residents from their homes or destroyed property value. Added to these harms, school closures sent another message that black communities, black lives, did not matter.

With city schools shuttered, busing put black students in schools far from home for nine or 10 of their 12 years of schooling. Most white students traveled for only two or three years. For all the good achieved by busing in some areas, being far from home diminished students' after-school opportunities and lessened parental access, especially for those dependent on Nashville's meager public transportation.

Among them was McGavock High School star basketball player Charles Davis, who worked hard to catch the school bus each morning from the J.C. Napier Homes. Not only that, he had to find a way home after practice or games, as the buses didn't run then. Fortunately for Davis and his teammates, McGavock Coach Joe Allen saw these transportation problems as learning opportunities. Coach Allen asked teammates like Steve Flatt, who lived close to McGavock and had a car, to drive home those who didn't.

He also asked his players to host team dinners in their homes, whether they lived in Napier and Sudekum public housing or in suburban Donelson. Both Flatt, a future president of Lipscomb University, and Davis, a future pro basketball player who spent eight seasons in the NBA, spent time in parts of the city and with communities they hadn't known before. Fellow coach Milton Harris hoped the students took a message from these dinners: "It didn't matter where you lived, but how you lived in the place that you lived."

From that story, it's obvious Coach Allen believed black students and white students had much to learn from each other. Not everyone recognized this. At times in the throes of desegregation, a convoluted and troubling logic prevailed. The school board's attorneys in 1980 named white children the "primary educational resource" for black children.

Some white Nashvillians dismissed critiques of desegregation's unequal burdens. They said black children were desegregation's beneficiaries; that black communities were the ones who needed busing. What white students stood to gain as learners and as citizens — how schooling alongside black students could broaden the too-narrow worldview cultivated in segregated white schools — went missing.

Often, when desegregation treated black students differently than white students, it did so in the name of mitigating white resistance and withdrawal. Certainly, middle-class and elite white families' departures to surrounding school systems or private schools helped produce major shifts in Nashville school demographics. These created political and economic challenges the school district is fighting to this day.

Yet because of busing's metropolitan scale, Nashville saw less white flight than did systems with separate city and suburban districts. When busing for desegregation ended in 1998, the school district's population was roughly half white students, half students of color (the vast majority of whom then were African-American). Nashville schools continued to lose more white students, and more middle-class students, after the end of busing for desegregation. But the idea of "white flight" had captured education policymaking in Nashville. Fear of white flight pushed the school district often to think of white and middle-class students as their most important constituency.

How much should a district focus on the students it wants to have, rather than the ones it does? Today, with the return of middle-class and wealthy families to Nashville's city neighborhoods, the district may see the opportunity to regain economically and socially privileged constituencies, and broaden public support for its schools.

Crafting district policy in the hopes of doing so, however, has costs. After studying Philadelphia's efforts to gain and retain middle-class families, Temple professor Maia Cucchiara argues that "policies designed to create diversity ... particularly those that use market strategies and incentives to attract the middle class, can result in the marginalization of low-income families." If desegregation is to return to the policy conversation, both Brown and black lives must matter.

One point is clear. After decades of leading the nation in statistical desegregation, Nashville has regressed to the mean. If the district is to reengage with segregation as a problem, the accomplishments as well as the failures of the busing years will be crucial. Leaders will have to transcend the shape of the current education debate, too long focused on controversial interventions like charter schools rather than broader efforts to confront underlying, continued and complex sources of educational inequality.

The prime question is how frankly, how deeply, how assertively the city will value the schooling of its children, naming equity as a goal and attending directly to the needs of the black and poor children Nashville has historically neglected most. Those students today are most likely to attend sharply segregated schools, farthest from the educational benefits of the city's diversity, and to live in communities most removed from the economic benefits of the city's growth.

Perhaps busing for desegregation seems a relic of a distant era. But recent events, from Ferguson to Charleston, demand that Americans register the ways that inequalities and injustices decades earlier shape lives today. To paraphrase William Faulkner's oft-quoted maxim, Nashville's desegregation story — its accomplishments, its missed opportunities, its inequalities — shows that the past isn't even past.

Sources for this article

This article draws on more than a decade of research on Nashville's schools for my book, Making the Unequal Metropolis: School Desegregation and Its Limits, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in March 2016. My interpretation of the city's approach to desegregation and its consequences comes from reading the voluminous records of Nashville's desegregation case over its 44-year history (at the National Archives location in Morrow, Georgia), the many relevant collections of city records, and individual and organizational collections at the Metropolitan Archives of Nashville-Davidson County, the Nashville Public Library Special Collections, the Tennessee State Library and Archives, and Vanderbilt University Special Collections and Tennessee State University Special Collections. I also draw from the coverage of schools in the Nashville Banner and The Tennessean. Additionally, I was fortunate to conduct interviews with more than 60 Nashville residents who lived through this history from a variety of perspectives and kindly shared their stories with me.

For more on Nashville's desegregation history:

John Egerton, "Walking Into History"

Ellen Goldring, Lora Cohen-Vogel, Claire Smrekar, Cynthia Taylor, "Schooling Closer to Home: Desegregation Policy and Neighborhood Contexts," American Journal of Education, May 2006

Richard A. Pride and David Woodward, The Burden of Busing: The Politics of Desegregation in Nashville, Tennessee (University of Tennessee Press, 1985)

For more on segregation, inequality, metropolitan desegregation and inclusionary zoning, see:

Ta-Nehisi Coates, "The Case for Reparations"

Alana Semuels, "The City That Believed in Desegregation"

Gerald Grant, Hope and Despair in the American City: Why There Are No Bad Schools in Raleigh (Harvard University Press, 2010)

This American Life, "The Problem We All Live With," July 31, 2015

Heather Schwartz, "Housing Policy is School Policy," (2010)

Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren and Lawrence Katz, "The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children," (2015)

Colin Gordon, "Growing Apart: A Political History of American Inequality"

Email editor@nashvillescene.com

A group of elementary school students, some of them clutching the hands of their parents, awaits the arrival of Metro Bus 185 in North Nashville. Sept. 8, 1971.