Gary Antol sat outside the bunkhouse strumming his guitar in a pool of manufactured light. A budding musician who should have kept Yellow Cab on speed dial, Antol was serving time for his third DUI. Only he wasn't in a cell.

Because he hadn't knocked over a bank or hit his girlfriend, Antol was considered safe enough to help out at the Andrew Jackson Police Youth Camp, run by the local police union. He got to spend the majority of his year-long sentence on Old Hickory Lake in Mt. Juliet. Cleaning up after the officers and kids wasn't the best gig in the world, but it beat the alternative.

At just before midnight the phone rang. Somehow, the voice on the other end of the line knew his name. He called himself Mike. He was with Internal Affairs.

Are you alone? he asked Antol. Can you meet me by the basketball court?

Antol hadn't made it 50 yards when a man materialized from the trees, whispering his name. He was tall and clean-shaven with close-cropped blond hair. He flashed a badge, but what was the use?

Mike looked like a lot of things: a dad, definitely. An ex-high-school-linebacker, maybe. But without a doubt, what Mike most resembled was a cop.

The cops come up here to party, he told Antol. They get drunk, get mean and mess with the kids. Internal Affairs was going to set up surveillance to catch them in the act. Antol was to be their inside man.

"Cooperate and we'll talk to the judge," said Mike.

"And if I don't?" asked Antol.

"We find someone else," said Mike. "And you go back to a cell."

Antol didn't have much choice. Mike handed him two $100 bills and a cell phone and told him to wait in the lodge for his call.

Mike returned minutes later with two men in a white Chevy Astro van. Posterboard covered the side panel and a pinch of electrical tape obscured the license plate. The men got out holding walkie talkies and carrying briefcases filled with what looked like recording equipment.

For three hours Mike and Antol talked while the men went to work, wiring an empty bunkhouse with two small cameras. Antol told Mike about his dreams of going home to Pennsylvania, marrying his girlfriend and fronting a country band. Every so often the walkie talkie would crackle with the sound of a woman's voice pleading for an answer. "Are you guys done yet?"

But Antol couldn't wait until the operation was finished. Exhausted from a night where he'd gone from inmate to informant, he went to bed around 3 a.m.

He fell asleep that night assuming he was now working for a cop named Mike. Only Mike wasn't really Mike. Nor was he from Internal Affairs.

He was actually Calvin Hullett, a former lieutenant for the Metro PD, a man who should have known better than to run a game like this.

Some people find their calling early in life. So it was for Hullett.

On the night he was born in 1963, one of Hullett's first visitors was Police Chief Joe Casey. Hang 'Em High Joe didn't make it a point to pay respects to all of Nashville's new infants. But seeing as how Hullett's mom ran the records division at headquarters, an exception was in order.

Hullett's parents were divorced. His mom matched the detectives hour-for-hour down at the precinct. So when it came time for after-school care, the officers at the old Public Safety Building played babysitter.

Little Hullett's first stop was always the information desk. The lieutenant in charge was too old to care that the kid heard all the incoming calls; the veteran cop got a companion, and Hullett got an early listen into the town's secrets.

From there it was eight steps up to records where mom worked. Casey's office was to the left. Bathroom straight down the hall. That's where Hullett learned what happened to those who dared to gun down a member of the Metro PD. The details of the incident are lost to memory, but Hullett can still see the perp, his face swollen two shades toward turnip, his wrists handcuffed behind the porcelain so that he and the toilet bowl remained locked in intimate embrace for hours.

These were men who looked out for their own. That included Hullett.

When a fight had him one step away from expulsion, it was a homicide detective who convinced Hillsboro High's principal to let him off with a slap on the wrist.

"Police and police work," says Hullett, "that's all I ever knew. It was only natural for me to follow that path."

He started in Brentwood dispatch at 18 years old. From there it was Metro, then Mt. Juliet, then back to the city to work a beat.

A sergeant's rank came in 1998. Lieutenant six years later. By the time he left in 2006, forced into early retirement by a back injury, he'd logged more than two decades of service. More important: Hullett had become the guy he'd always wanted to be. A cop's cop.

For nearly 30 years, being a cop in Nashville meant you were FOP. The Fraternal Order of Police, the largest cop union in the country, represents 1,300 officers in Music City. For a time, Hullett was the man in charge.

Hullett became FOP president in 2001. The leadership post suited him. Meticulous and detail-oriented, Hullet kept records like you'd expect from the son of a secretary.

"With Calvin there's a file for everything," says his wife Mary. "Right down to the dog's rabies shots."

Another strength: his relative fearlessness in the face of hierarchy. It could be a double-edge sword in a politically charged bureaucracy like a police force. Take the time he got fired in Mt. Juliet for having the future mayor's car towed. But it was an essential trait for survival of a union head.

"Calvin sometimes sees himself as a bit of a crusader," says his best friend, Sgt. Marvin Keith. "And that can get him into trouble."

But it can also get results.

When Hullett took over the FOP, cops in Nashville earned less than their counterparts in nearly every other comparably sized American city. Yearly pay raises meant a three percent bump. Decent, but not enough to make up the difference. Hullett had found his mission, and with it a tactic: Shame the city into paying up.

Hullett and the FOP created a slogan–"Low Pay–Nashville's Biggest Cop Killer"–and bought space on a billboard facing then-Mayor Bill Purcell's office. Purcell's deputy mayor Bill Phillips put the squeeze on the billboard company's owners, claiming the sign might compromise the company's relationship with the zoning board. The FOP squeezed right back. So the company compromised with a "We Support Nashville Police" sign that ran free for four months.

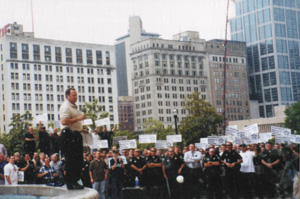

Not satisfied, Hullett bought a rusted-out Dodge flatbed, mounted it with protest signs, and parked it outside City Hall. Then he organized rallies with upward of 700 protestors. The strategy worked. When the city finally caved, Hullett's public shaming brought back a 20-percent raise across the board, with some cops nearly doubling their salaries.

"In the history of this city," says Keith, "no one ever earned more for his fellow officers."

But Hullett's willingness to agitate also had unintended consequences. In 2003, he openly campaigned for Phil Bredesen during the former mayor's second run for governor. This despite the fact that the local FOP backed his opponent.

The glad-handing earned him enemies within his own union. But it also got him a spot on the POST commission, a powerful governor-appointed board that provides waivers to cops who don't meet all the requirements to wear the badge.

In 2005, Hullett became chairman of POST. The first order of business: Five waiver requests from Nashville's new chief, Ronal Serpas. The cops all had criminal records. In some cases even felonies. Hullett drew a line in the sand.

Saying "this isn't New Orleans"–a reference to Serpas' notoriously corrupt hometown–Hullett denied the requests, effectively outranking his boss. The results were swift.

After news broke that Nashville's head cop was vouching for former criminals, Serpas sought revenge, knocking Hullett down from his Lieutenant's post at Central Precinct and exiling him to the impound lot.

The demotion was meant to send a message. But Hullett had already made his mind up about Serpas.

Hullet's term as FOP president had expired, and he thought the new leadership was too cozy with the chief. So he began sending feelers out to the Teamsters. His pitch: The rank-and-file were fed up with Serpas' stats-oriented approach to policing, which made traffic stops and writing tickets Mission One. If the Teamsters tied the FOP to an unpopular chief, they could become the new union of the Nashville police.

The group made notorious by Jimmy Hoffa was more than willing to listen. Teamsters membership had been declining for years due to manufacturing losses and the union's legendary corruption. So Teamsters organizing was shifting toward people with more job security: cops. The results, however, were not impressive.

The union represented police scattered all over the country, but only in small numbers. A dozen in Wilmerding, Pennsylvania. Forty more in Dallas County, Iowa. Nashville was to be their big score. And with the FOP's national headquarters in Music City, the Teamsters had extra motivation: Embarrassing a rival on its own turf.

Teamsters organizers flooded the city. Rotating in 50-60 member "SWAT Teams," the union hammered call lists, promised pensions and stood en masse outside of precincts in a show of force. The battle divided the force, reducing roll calls into Hardball-style shouting matches.

Some members claim the Teamsters spent over $1 million in hopes of defectors. Their biggest was Hullett.

In 2005, he signed on as a national organizer. Hullett helped the Teamsters paint the FOP as too cozy with the chief and more fraternal organization than union.

For Hullett, it was also a chance to settle a score. Not just with the chief, but to those who'd fought against him in the FOP.

"I love the man to death," says Keith. "But Calvin's biggest problem is that he holds a grudge."

And the battlefield for that grudge would be the Andrew Jackson police camp.

Located on 30-plus acres off of Old Hickory Lake, the land was a gift from the Corps of Engineers. The only condition: The FOP had to run a youth camp.

The union obliged by setting aside six weeks during the summer. Each week, a different FOP leader would bus 50 inner-city kids and match them with 10 handpicked police counselors.

The reasoning was solid: Take some troubled kids to the great outdoors and show them that cops are people too. The kids get to swim, canoe and play ball all week. The cops get paid to play mentor. Everyone wins.

But just as often, says Hullett, the camp was used as a frat house. The heavy drinking and late-night parties led to a combustible mixture of hungover cops and kids not afraid to talk back.

"There's probably more beer drank on that hill in a weekend than at a Titans football game," says neighbor Darryl Guffey.

Complaints from Mt. Juliet residents would be familiar to anyone with rowdy neighbors. The music's too loud. They come and go at all hours. Nothing changes no matter how much we bitch. The difference was that the people causing the problems were the same people they'd normally call for help.

"The attitude is 'You can't touch us,' " says Guffey. " 'We can do whatever we want to and you can't do anything about it.' "

Hullett's first taste of the problems at Andrew Jackson came in 1997. At the time, he was the FOP board's secretary, and he heard testimony from female police officers that the youth camp was a glorified boys' club.

Along with the boozing, the female officers were particularly troubled by one rule: When coming out of the pool, kids were forced to hang their swim trunks on a line outside their bunkhouse. It left them naked for the sprint to get their clothes.

The FOP spent a day conducting interviews to make sure the claims were accurate. A recommendation to relieve East Precinct officer Jeannine Hale of her duties as camp director was the result.

When she refused, Hullett brought a motion to dismiss her. Deadlocked, President Keith cast the deciding vote. And that, says Hullett, is where his troubles all began.

"From that day forward there were two factions within the FOP," he says. "One with me and one against me."

Included in the one against was Danny Hale, Jeannine's husband. The year after his wife was relieved of her camp director position, Hale was voted onto the FOP board. Hullett claims his first meeting as president featured a drunk Hale, cocking and uncocking his service revolver in what Hullett took as an act of intimidation. (Both Hales refused to comment.)

Hullett continued a steady rise in the union. At the same time, the opposing faction held a majority on the board, and Hale got her job back.

Hullett says he tried to take small measures to ensure kids were safe. He taped signs up at the camp's lodge limiting guests and reminding officers that alcohol was prohibited. And for the week he ran the camp with Keith, he personally tracked down kids who he thought would benefit from the experience. But word came back that the heavy drinking and abuse continued. So Hullett went outside the FOP.

First he contacted Serpas. But according to Hullett, a confrontation with the Chief at a weekly Comstat meeting yielded no results. (Through a spokesman, Serpas refused comment.) So Hullett turned his attention to the media.

"I thought if I couldn't get them to police themselves I'd just embarrass them," he says.

A Teamster official got him in touch with Channel 5 reporter Phil Williams. Hullett and Williams met at a Smyrna Starbucks. For two hours they drew maps of the camp and brainstormed increasingly complicated ways of getting evidence without breaking the law, including a manned boat on the lake filming 24/7 surveillance.

In the end the legal obstacles were too much. Williams told Hullett to get back in touch when he had proof and left him with a word of caution, strongly recommending that Hullett talk to a lawyer before going it alone.

"I wish he'd taken my advice," says Williams.

Hullett may have been losing his audience with the media, but the Teamsters were all ears.

Hired to recruit other police forces, Hullett had a new job: to spread the gospel, touting the FOP's lapses. And the verse he most often recited came straight from Andrew Jackson.

"It embarrassed the FOP that their former president flew around the country talking about how they were abusing little kids," he says.

The story may have been a killer on the recruiting trail. But it was getting an even better reception back at Teamsters HQ.

Retired Seattle Port Authority officer Ron Collins first met Hullett during the Nashville organizing offensive, where he'd been sent to press the flesh.

"Calvin talked about this all the time," says Collins. "Every time you'd get together he'd always revert to how he wanted to do something about these kids in this camp. I didn't pay a lot of attention to that."

But someone else did. At a Seattle bar after a conference, Hullett's story caught the interest of a Teamster executive. How much would it cost? she asked.

"All I remember him saying is 'a few thousand dollars,' " says Collins. "So she says, 'Well, you find out how much and I'll get the money.' "

In May of 2007, Hullett went to Washington, D.C. with Jesse Case, the Teamsters' national campaign coordinator. Hullett told his story to a roomful of higher-ups. They ate it up.

That same afternoon, says Hullett, they held a conference call. On one end were Jimmy Neal and Joe Bennett, president and treasurer for the Nashville local. Everyone agreed the national chapter would give the local $10,000 for Hullett's operation, he claims. One executive was so excited, Hullett says, that she jumped online to Google spy-equipment stores in D.C. (Through a representative, the Teamsters refused to comment.)

Hullett now believed he had the money and full backing of his union. So he began to set up a surveillance team.

Through Case, Hullett found Joe Everson, a Shelby County sheriff's deputy with a surveillance business on the side. Through another friend he found David Dickerson, a local roadie with MacGyver wiring skills. Hullett also learned the identities of the two inmates working at the camp. Gary Antol, serving a year for his third DUI, seemed like a logical informer.

Nashville local leaders Bennett and Neal cut Hullett the checks. And the three had a good laugh when picking a fake name with which to buy cellphones. They settled on Mike Kreugel, an ex-Teamster who'd jumped ship to the FOP.

The last link in Hullett's Mission: Impossible squad: a look-out. The married Hullett filled the spot with his girlfriend, Amber Kitchens, though it would take $100 and some mild coaxing.

The day after their covert installation of cameras, Hullett says he called Case and Neal to report the good news. Then he waited.

But two weeks on the phone with Antol brought little. Hullett returned to the camp to give Antol cash and cigarettes and to switch out the tapes. Humming from the recorder was loud enough to be heard outside the bunkhouse, said Antol. So Hullett wrapped it in a towel.

During the Fourth of July, Hullett and Case were at the home of a Daytona Beach Teamster. On the kitchen counter was Hullett's laptop. That week, he says, the three watched the latest tape: A grainy black-and-white that showed cops shooting bottle rockets at the kids. Hullett was convinced his ammunition was about to get much more lethal.

On July 9, Hullett called Antol. Watch out, he said, this is Danny Hale's week to run the camp.

Hullett was expecting heavy drinking from his nemesis. The next day he was proven right.

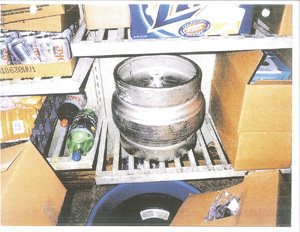

Antol called to say that the walk-in cooler was now stocked with two kegs and four cases of beer. The cops were clucking about a big birthday that night, and the party was starting early.

By 1:30, Antol had left Hullett four voicemails, each sounding more concerned. The last one said that the cops had moved a keg into Hale's RV and were getting "torn up." Hullett claims he consulted with Case, and the two decided now was the time to make a move.

Through an anonymous Yahoo! account, Hullett posed as a concerned cop counselor and emailed Serpas. In less than an hour, two uniformed captains were searching the camp. Channel 5's helicopter circled overhead.

Antol called Hullett to warn him that the captains were searching the wrong places. They weren't looking in the RV. So Hullett wrote Serpas again with more specific instructions. But by that time, the chief had already gotten wise to his game.

Serpas had tracked the Yahoo! account to Hullett. Within 24 hours, Antol would confess to being the informant. For the next three days, the conversations between him and Hullett had a silent third party listening in on the line: The Tennessee Bureau of Investigations.

At 10 p.m. on July 14th, Hullett stepped out of his Dodge Ram at the gate of the camp. On the other side of the fence, Antol stood with a bag of tapes, waiting to make the drop.

Lying in wait were eight Wilson County SWAT Team members, four TBI agents and two snipers.

Hullett handed Antol $400 and a carton of cigarettes in exchange for the tapes. But as soon as he grabbed the bag he knew what was happening. It was empty. He turned around to face gun barrels.

According to TBI, Hullett resisted arrest, initially telling the agents to "fuck off," then reaching for a Wilson County deputy's revolver. Hullett denies the claim. He says he was forced to the ground and kicked repeatedly, with his face smashed into concrete. The beating was so severe, he says, he pissed himself. A doctor's report later revealed two cracked ribs.

Hullett was charged in Wilson County with aggravated burglary. Meanwhile, the Teamsters closed rank. They admitted to conversation about surveillance, but in the end, Hullett had acted as a lone vigilante. To some members of the union, that was an implausible defense.

"I can guarantee you the Teamsters did not write a check for any amount of money without knowing exactly where it went," says Seattle Port Authority officer Collins. "They always said, 'We're being watched by the Feds. We have to be very careful.' They wouldn't cut one for $10 without knowing what it was going for."

In exchange for immunity, Bennett, the local secretary, claimed Hullett lied to him about the true purpose of the $10,000. But Hullett says Bennett was just covering his own ass.

In 1985, Bennett and his father were seen driving a truck that belonged to a man who happened to be slumped over dead in the front seat. A year after he was found not guilty of first-degree murder, Bennett was convicted of hiring a hit man to kill another member of the dead man's family. Bennett was sentenced to nine years but got out in 18 months. He served more time a few years later for a gun charge. But he'd kept clean long enough to be elected the local's secretary. (Neither Bennett nor local president Jimmy Neal would comment for this story.)

Meanwhile, the feds dangled a deal for Hullett. Plead guilty to embezzling the 10 grand and we won't reveal your little secret.

That secret was Hullett's girlfriend, Amber Kitchens. The night before Hullett's first court appearance, Kitchens was served by a TBI agent.

"He told me when Calvin finds out about this he'll drop what he's doing and give in," says Kitchens, "because he's not going to want his wife to know about you."

But Hullett refused the plea. On the drive up to court, he told his wife about the affair.

"(This case) has ruined all of our lives," says Mary Hullett, who's since filed for divorce.

In March of last year the feds finally brought charges. Hullett was on an island. Everson, the Shelby County deputy who helped install the surveillance equipment, took early retirement and received six months probation for initially lying to authorities about being at the camp.

And the Teamsters were no longer allies. To prosecutors, they were now victims, duped by Hullett into funding his secret operation.

When the case began, Hullett was confronted with even greater troubles. The judge declared that Bennett's criminal past was not admissible, meaning his testimony wouldn't carry the color of someone once convicted of hiring a hit man. Nor could Hullett discuss his suspicions of abuse at the camp, the very reason for the break-in. With his best weapons neutralized, Hullett had no choice but to plead guilty. His sentence: 10 months in federal prison.

Now, sitting in the same Starbucks where he first made his pitch to Phil Williams, Hullett says he's reached bottom.

Police rules dictate that officers can't consort with felons. Sergeant Keith and two others were bumped down to desk duty for a week after being caught having dinner with Hullett at Hooters.

When Keith's mom died in February, he begged Hullett to be a pallbearer. But Hullett had to decline, knowing it would only mean more punishment for his friend.

Meanwhile, his Blackberry buzzes with calls he can't answer. They're from creditors he's trying to duck. Hullett is now $200,000 in debt from lawyers' fees and restitution. Financial straits have forced him to sell his daughter's Barbie collection just to pay the lawyer who's filing his bankruptcy.

"I've lost my wife, my family, my friends," he says. "I've got nothing left. My heart's broken."

Left unspoken is what happens to the career he'd dreamed of since he was a kid. Felons can't get a job at Dunkin' Donuts, let alone Metro PD.

May 20th doesn't just represent the day Calvin Hullett went to prison. It also represents the day he became something different. Something he'd defined himself against his entire life. On that day, Hullett became one of them: The guys he'd spent his whole life trying to lock up.

Email channan@nashvillescene.com, or call 615-844-9410.