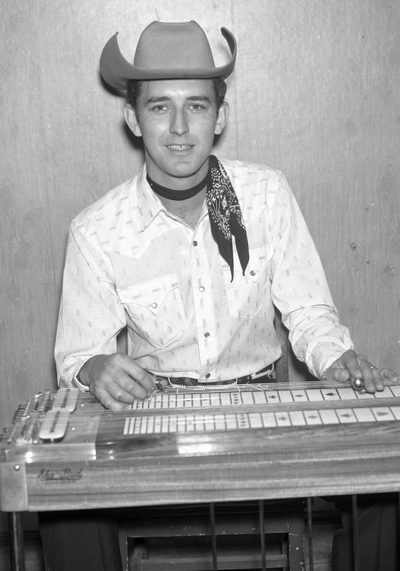

Buddy Emmons

Buddy Emmons, who died yesterday in Nashville at age 78, achieved the kind of exalted position among musicians and listeners that few instrumentalists in the history of country music have equaled. In his hands, the pedal steel guitar became a vehicle for the kind of sophisticated expression that enriched the work of pop musicians, jazz players and country singers. But Emmons was not only a superb technician of his chosen instrument.

Working with fellow pedal steel guitarist Harold “Shot” Jackson in the late '50s, Emmons revolutionized the instrument through a series of technological advances that would profoundly affect the way all subsequent players approached it. His innovations helped the pedal steel transcend some of its previous association with country music, but he made part of his reputation playing with such country singers as Ray Price, Ernest Tubb and Little Jimmy Dickens. A formidable and forward-thinking musician and consummate session player, Emmons was as comfortable with advanced jazz harmonies as he was with the structures of the three-minute single.

Born Buddy Gene Emmons in Mishawaka, Ind. on January 27, 1937, and influenced by steel guitarists Jerry Byrd and Herb Remington, he began his career working clubs in South Bend, Ind. By 16 he was playing in Calumet City, Ill. honky-tonks with singer Stony Calhoun. During that tenure, Emmons caught the ear of country great Carl Smith, who recommended the young musician to Webb Pierce. That job didn’t materialize, and Emmons moved to Detroit, where he sat in with Little Jimmy Dickens in 1955. He moved to Nashville that summer to play in Dickens’ band.

Inspired by Buddy Isaacs’ steel guitar work on Pierce’s 1954 recording of “Slowly,” Emmons began developing the style and the technological curiosity that would revolutionize pedal steel style. Dickens supported Emmons’ ambitions — as Emmons told Steve Fishell in a 2013 interview at the Country Music Hall of Fame, “Jimmy Dickens loved what we were doing, and he was so proud of his band that he talked Columbia Records into recording us under Jimmy’s band name, the Country Boys.” Over the next year, Emmons would record a series of singles under his own name.

Emmons played on Faron Young’s 1956 “Sweet Dreams,” before joining Ray Price’s band in 1962. He played brilliantly on Price’s 1963 “Night Life” and “You Took Her off My Hands (Now Take Her off My Mind),” and became Price’s band leader. It was during his association with Price that Emmons added extra strings to the pedal steel, an innovation that allowed him to more easily navigate the instrument. He also developed a new system of pedals that were designed to raise the fretboard. Emmons would continue to refine his modifications of the pedal steel, and his technological savvy and willingness to experiment would open up possibilities for the instrument that players continue to use today.

Ray Price - Night Life

With Shot Jackson, Emmons started the Sho-Bud Guitar Company in 1955. Emmons and Jackson parted ways in 1963, and Jackson moved Sho-Bud into a space at 416 Broadway in Nashville two years later. With his newly formed Emmons Guitar Company, Buddy created his own version of the pedal steel by scaling down the size of the instrument’s cabinet and creating a two-piece aluminum neck with a bridge that mounted on the cabinet. Emmons’ technological innovations went hand-in-hand with his playing, which revealed his affinity for jazz and his ability to conceive beautifully articulated parts for recording sessions. In 1963, he recorded a full-length called Steel Guitar Jazz — a touchstone for pedal-steel players. After parting ways with Price in the late '60s, Emmons played bass in Roger Miller’s band. In 1967, he moved to L.A, having lived there briefly in the late '50s after a stint as lead guitarist for Ernest Tubb’s Texas Troubadours. Emmons married his third wife, Peggy, that year, and he always acknowledged her support of his career. As he later wrote, “In our early courting days, she told me, ‘You must be good. Everyone says you are.’ I roared with laughter, because the funny part about it was, she wasn’t trying to be funny.”

Buddy Emmons - Pedal Steel Guitar

Danny Gatton - Guitar

Steve Wolf - Bass

Scott Taylor - Drums

CD Liner Notes by: Brawner Smoot:

Tonight the Cellar Door club, sold out weeks in advance, is owned by Danny Gatton's instrumental aggregate, the Redneck Jazz Explosion. The crowd has come to see not only the guitarist presenting his virtuosic wares in all instrumental jazz setting but his pairing with pedal steel maestro Buddy Emmons. To quote Ralph Heibutzki from his 2003 biography, "Unfinished Business-The Life Times of Danny Gatton," the December 31, l978, Cellar Door gig has assumed legendary proportions for its place in Gatton history. Swearing you were there is akin to saying you saw the Beatles at the Cavern Club or caught the Yardbird's hot, sweaty nights at the Marquee." It's a great tribute to Danny that Buddy Emmons, who had not been on the road for years, did hit the highways with the Explosion.

Let's set the stage. It's D.C.'s six string's finest as the Tom Principato-Pete Kennedy duo, propelled by the Explosion's electric Fender bassist Steve Wolf, open the show. They lead you through a mini-history of guitar instrumentals like Les Paul's "The Kangeroo", Merle Travis', "I'll See You in My Dreams" and Roy Nichols' "Stealin' Corn" (for an audio sampling of eight tunes from this era check out their CD "Fingers on Fire" on Powerhouse records recorded December 30, l978).

But the real magic starts after intermission as Danny, Buddy, with trademark derby in town and rhythm section (the aforementioned Steve Wolf and drummer Scott Taylor) uniformly clad in red T-shirts with their names on the front and the words Redneck Jazz Explosion around a cloud and lightning bolt emblazoned on the back assume the stage. The Voice of the Cellar Door, David "Dude" Sless announces, "The Cellar Door is once again proud to present the Redneck Jazz Explosion."

Emmons worked with a staggering number of artists during the '60s and '70s, including Gram Parsons, Judee Sill and John Phillips. He also worked with George Jones, and examples of Emmons’ inspired work can be found on Jones’ Live at Dancetown U.S.A., a set of 1965 recordings that was released in 1992. On the record’s rendition of “White Lightning,” Jones tells Emmons, “Play me somethin’ wild,” and Emmons obliges him by turning in a superb six-bar solo.

From "Live At Dancetown USA"

Emmons also worked with jazz vibraphonist Gary Burton on Burton’s 1967 Nashville-recorded full-length, Tennessee Firebird. Emmons added full-bodied licks to the record’s “I Can’t Help It (If I’m Still in Love With You).” As his work on Tennessee Firebird and later recordings with guitarist Lenny Breau demonstrated, Emmons was comfortable in a jazz setting, and it’s his jazz chops that distinguish his work from that of similarly celebrated pedal-steel players such as Lloyd Green and Weldon Myrick. Emmons aficionados also point to his 1970 full-length Emmons Guitar Inc., along with his solo on Ray Charles’ 1971 version of Jim Webb’s “Wichita Lineman,” as some of his best work.

After returning to Nashville in 1974, Emmons played sessions and made regular appearances at St. Louis’ annual International Steel Guitar Convention. He formed a band, The Redneck Jazz Explosion, with guitarist Danny Gatton. In 1991, he began touring with The Everly Brothers, and stayed with them for a decade. He ceased playing in 2001 after injuring his right thumb — a consequence of his disciplined practice habits.

A perfectionist, Emmons said he played in the dark in order to be prepared for the chance that he could go blind. He had other unusual practice methods. “I started worrying about what happens if I lose that finger, or two, or a thumb, or whatever," he told Fishell in 2013, "so I would practice with these two fingers that way, and just a thumb, then just three fingers." Marty Stuart, who recorded with Emmons in the '90s, tells the Scene that Emmons was among the greatest musicians of his era. “His abilities were so vast that he just took it into this unknown place,” Stuart says. “So many steel players took their cues from him.” Dean Miller, whose father, Roger Miller, worked with Emmons, took part in the 2013 Country Music Hall of Fame tribute, and he got to know Emmons in the '60s. “[He was] very quiet, but very funny,” Miller said. “He was very sharp and on top of things.”

After his wife’s death in 2007, Emmons retired. I saw him play at a May 2008 show at the Country Music Hall of Fame with Texas-born singer-songwriter Johnny Bush. They performed Bush’s 1967 “Sound of a Heartache,” to which Emmons had contributed a typically astute pedal steel part. It was an unforgettable moment. Leaving the Hall of Fame, I ran into Emmons on the steps outside. I could think of nothing to say and nothing to ask him. I felt as though I were standing next to Charlie Parker. Finally I said to him, “So, you guys were listening to bebop back in the day, Mr. Emmons?” He looked at me and he said, “Yeah.”

this upload is for Brit1234ish