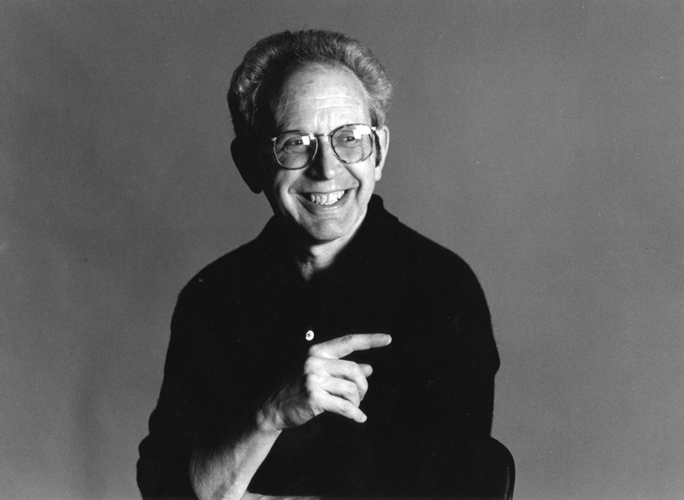

Author, journalist and Vanderbilt lecturer Peter Guralnick has written a host of critically acclaimed biographies, as well as profiles and portraits, of both extremely popular and very obscure musicians over his impressive career. Some (Elvis Presley, Sam Cooke) are legends. Many others are marvelous, sorely underrated performers (Stoney Edwards, Sleepy LaBeef, Billy Lee Riley, etc.) who never enjoyed great commercial success, yet made remarkable music.

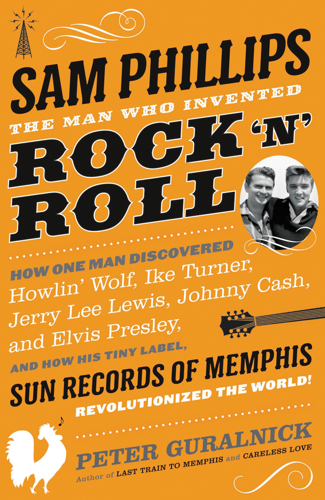

But his latest volume covers a different, though not less important, individual. Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock 'n' Roll, published last fall, spotlights the flamboyant maverick producer and Sun Records founder, whose innovative work laid the foundation for rock 'n' roll. Guralnick's book not only documents many musical highlights involving Phillips, it also presents an intriguing thesis regarding his life and impact.

Guralnick sees Phillips as a visionary on race, and considers his quest to record black performers emblematic of Phillips' overall desire for racial justice and equality. This despite the fact that for a sizable portion of its existence, Sun Records' involvement in black music was minimal to nonexistent, and that after a heyday that saw Phillips issue superb recordings by Howlin' Wolf, Little Milton and Rufus Thomas among others, his fame was cemented on the basis of music from famed white artists like Charlie Rich, Roy Orbison, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis and, most notably, Elvis Presley.

Though the book, typical of Guralnick's work, has mostly garnered rave reviews, there have been a few critics of the contention that Phillips saw what he was doing as contributing to the fight for racial justice. One Amazon reviewer pointedly claimed the book doesn't effectively make its case, and that Sun's track record shows only that Phillips wasn't bigoted, not that he had any real interest in civil rights.

Guralnick's a busy guy, but we got him to take a few minutes and answer some questions about Phillips and race.

Writer's note: For the record, Guralnick and I have been friends for decades. Also, I was fortunate enough to meet Phillips in Memphis, talk with him on several occasions, and even form a mild friendship, though nothing remotely close to the relationship enjoyed by Guralnick.

Sam Phillips, by pretty much any yardstick used for that era, had a more progressive attitude in regard to race than many of his contemporaries. Did you ever have discussions with him that were strictly on racial rather than musical issues? Oh sure. He spoke about race all the time. He saw the music as breaking down the walls of segregation. This was his vision for the music long before he opened his studio on Jan. 2, 1950. He considered the March on Washington the most significant historical event in his lifetime.

Did he consider the recordings he made with blacks something to advance the cause of equality, or just a matter of him enjoying certain types of black music and saw recording it as good business since so many others were ignoring the market? No, he saw it as totally challenging the racial status quo, in fact the conventional status quo, of the time. From the age of 5 or 6 on, he believed in treating everyone equally, and he expressed himself volubly on the subject. His first ambition was to be a criminal defense lawyer, like Clarence Darrow, to right some of the wrongs of society. One time he said to me about the music he had recorded, black and white, "We really hit things a little bit, don't you think? Together," he said. "I think we really knocked the shit out of the color line."

Why did he never establish his own blues or R&B company? In effect, he did, the first five years he was in business. He opened the studio, as he said over and over again at the time, to provide the opportunity to "some of those great Negro artists in the South [who] just had no other place to go."

But he had no interest in establishing a label of his own — he simply wanted to record the music and leave the business to others. When he finally did establish the Sun label on something like a permanent basis in 1953, the first 20 releases — among the greatest recordings he ever made — were by African-American artists, as were most of the next 10 releases. Then, just as he was on the verge of bankruptcy, despite big R&B hits by Rufus Thomas, Little Junior Parker, Howlin' Wolf, The Prisonaires and others, Elvis Presley came along.

His interaction with Rufus Thomas was, to put it mildly, complicated. Thomas repeatedly denounced him publicly in later years, saying Phillips booted all Sun's black acts in favor of the white ones once the white artists started having hits. How should people regard these statements? Sam and Rufus remained close — in their way — to the end of Sam's life. I saw Rufus turn to Sam for advice over and over again. Rufus was the most successful of all his early artists — but, much to Sam's disappointment, Rufus left the label six months before Elvis arrived on the scene.

Rufus was one of the most wonderful people I've ever met, but he had an acute sense of grievance — against "Bones," his comedy partner with whom he emceed the amateur shows at the Palace Theatre, against the great songwriter David Porter, who Rufus felt forgot whose success Stax was built on (Rufus!), against some of his WDIA confreres who he felt did not always give him his due. I can't tell you how much fun I had with Rufus, or how much admiration and love and respect I felt, and continue to feel, for him.

But Sam was essentially a one-man operation — Johnny Cash left Sun in essence because he felt Sam was neglecting him for Jerry Lee Lewis. Sam considered one of his greatest faults the inability to delegate — he had time, almost literally, to focus on just one artist at a time.

Why didn't he continue on into the later black music of the era? Sam quit the business in effect around 1960 — he just withdrew from the day-to-day operations. He saw no future for the independent operator — he was convinced that the major labels, and eventually the international conglomerates, would gobble up everything in their path. And he was right.

Did he maintain friendships with black acts that he hadn't produced or black artists he hadn't met professionally? Sam was a very solitary person. He dedicated himself completely to his work in the studio. Even artists he admired enormously, like Charlie Rich, were distant social acquaintances. Probably the two artists he was closest to at the end of his life were Ike Turner and Jerry Lee Lewis.

Sam particularly loved Howlin' Wolf's music. But who are some black artists whose music he enjoyed who wouldn't necessarily be associated with him and might surprise people? Two of the artists that he most admired were Lightnin' Hopkins and John Lee Hooker. Their success in the late '40s — the success of the down-home music that he loved so much — served as a spur to his opening the studio. But to Sam's mind — mine, too! — no one touched the Howlin' Wolf, in whose music he famously said, "the soul of man never dies."

Email Music@nashvillescene.com