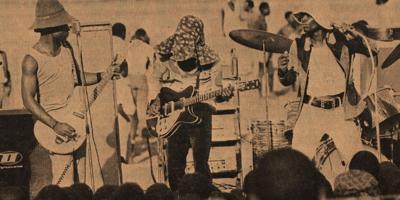

In the era before streaming services, W.I.T.C.H. — Zambian acid-rock masters whose name is an acronym for We Intend to Cause Havoc — was something of a specter outside Africa. You’d only hear them mentioned in conversations held in the far corners of record shops that sold used copies of Julian Cope books. But the group is getting the recognition they deserve from their reissues on Now-Again Records and a recent documentary that played screens worldwide.

The band’s singer, who goes by Jagari, has revived the Zamrock greats for their second tour of the United States. Monday night, they’ll play Third Man Records’ Blue Room. Opening for them is Paint, the solo project of Allah-Las’ Pedrum Siadatian. (If Allah-Las are revivalists of the best bands of the late ’60s and early ’70s, Paint mimics the solo work that came after — Brian Eno, Syd Barrett, John Cale and Kevin Ayers.)

Ahead of the show, I caught up with Jagari by phone. In our conversation, we talk about legacy, following the threads of influence, visiting Jimi Hendrix’s memorial site in Seattle and more.

Is it weird having a following of people who came to your music after you had already been recording and touring for 40 years?

Funny enough, it came like a surprise in the beginning. But later I realized that this has to do with God, because I’m a believer in God. Certain things that He prepares and plans, we cannot understand until we step into it. Then we see His love and power and mercy. For myself, [it’s not that I’ve been more careful or clever than] the guys who’ve since passed. It’s just that He had His own timing for my life, which looks like a resurrection to me. It’s like I was almost giving up on music. I started doing other things, like gemstone mining, so I could make a living on it. … I hope that probably if I strike big, I can establish a studio and a school of music for myself, as a way of trying to pass on the baton to the younger generation — that, to help Zamrock resurrect or carry on. So yes, it’s a surprise. But over some time I’ve come to realize it’s something to do with God’s plan.

When your first records came out, if someone wanted one in the U.S., they had to get a physical record shipped all the way across an ocean. And now — with the internet and streaming, among other technologies — they don’t. Do these changes affect how you look at what you’re able to do now that maybe you weren’t before?

It makes life easier for me. You see, the band that I’m traveling with is constituted by people from different parts of the world, Europe and Africa. One guy’s from Bulgaria, but he lives in Swizerland. Two guys are from the Netherlands, one guy’s from Germany, another one from the U.K., and I’m from Africa. And sometimes it’s difficult to find time for all of us to be together and create things together. So sometimes technology is an added advantage, because you can get an idea and post on their phone or something — some gadget. And your friends will be able to get that and contribute the way they feel it should be. By the time we are getting together for the actual recording, you will have exhausted some ideas separately. Then, collectively, you can come together and experiment some, recording. This is easier than the time that we started recording. The vinyls dont exist in my country anymore, unfortunately. So they come now — the cassettes, the CDs. Now look at the label we have!

I know you’ve talked about the influence of The Rolling Stones and British Invasion bands on your music. Did you see what you were doing as inherently different, or was it more of an extension of the same idea?

The way the music has reached, it’s like fashion: It goes, it comes back. Now the way it is, it’s very difficult to who has influenced who has influenced who. I grew up in the Federation of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland — that was Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi. Most of the people from there came to Zambia to work in the mines. That was the mainstay of the country. And because we had so many Europeans coming there — from the U.K., from South Africa — they brought their cultures there. And then we had only one radio station in Zimbabwe for the whole federation. So we had the same influence. I could listen to The Beat in Germany, I could listen to Lourenço Marques in Mozambique at night. And I was not the only one. A lot of the musicians of the time were listening to the same things.

We had only one record shop — until Teal Records came in — where we went to buy our records. And we signed with the only record company at that time. We were able to go and get free records from Piano House, which was a distributor at that time. And it was located in my area, where I grew up on the Copperbelt area. So, the same influences; we don’t know who has influenced who. There was some music from Africa that came over [to the U.S. and elsewhere] with the slaves, and then they started their own — bluegrass, whatever they brought, blues, jazz and things like that. And then the European bands also got influenced by the rock ’n’ roll of the Americas. Then, it went back to Europe and eventually came back to Africa. So it’s a vicious circle, musically; you find this one has influenced that one.

But when it came time to play, we wanted to play rock ’n’ roll, because that’s what we grew up with as the main genre of the time. But we were Africans, so we were limited to an extent. Our only advantage was the rhythms that criss-crossed. We used that, but in terms of the complexity of chords, chord progressions, arrangement of music, you guys are much better — even though there’s no competition. You are aware of so many things that pertain to music. That’s why you are able to have an orchestra — so many people playing the same thing. With Africa, the bigger side of us is the rhythmic patterns and the combinations of traditional rhythmic patterns, combined with the Western primary chords, pentatonic scales and things like that. Eventually we found ourselves almost doing some similar things as the Europeans did, as well as the Americans did. Yes, we were influenced by big bands — Deep Purple, Grand Funk Railroad, Led Zeppelin, a lot of Jimi Hendrix. Any musician in my country, guitarists, who didn’t play “Hey Joe” didn’t know how to play anything. [Laughs]

It’s very much that way in the U.S. Hendrix was just everywhere.

I was privileged — on the last tour in June we went to Seattle. We went to the area where Jimi Hendrix came from. We had the chance to go to the memorial center, and I left him a symbolic hat that represents the W.I.T.C.H. I left it on his guitar. Some people have left plectrums, things like that. It was like a dream, just to go see where this man is buried and how much he influenced the world musically. … No wonder why he didn’t live so long. Because influential people can’t handle what pressure they have on themselves. They don’t even realize they are influencing the whole world. … It’s my prayer that one day my band will be talked about as much as Jimi Hendrix was. [Laughs]

Recently, W.I.T.C.H. has become more widely known, thanks to many reissues; more Zamrock records are getting reissued, partly because of this. Do you see your work as having different effects, different fruits, than what you’d expected?

Yes, I do. Fortunately, I have very talented musicians surrounding me. They have given me a nice push such that, you know, it feels like the old times. And then you realize, “This is a new setup.” But the kind of talent? You can live anywhere in the world and appreciate it. They are very talented musicians. And they’re friendly and we move as a team, so I have every hope that even the new album that we’ve just done should be doing well eventually.

The guys that I’m playing with — most of them have their own band somewhere. But they leave their bands and they come and we play together on tours, such as the one we are undertaking right now. There’s hope. There’s much, much hope. Because if there was no hope, that music should have just died, like that. And probably someone would have just said, “This music is in oblivion. Can I pay a hundred thousand dollars and I keep it?” And someone, if I was dead, would have said, “Oh yeah. Sure, sure.” Because they wouldn’t have known the value of the stuff that we are keeping.

In touring the U.S., have you had any experiences of things that you never expected?

I didn’t expect the kind of favorable response that we are enjoying at the moment. We’ve had good shows, good gigs, wherever we’ve gone. Except, last week I was unable to follow the band into Canada, because my visa hadn’t been approved for the past five months. I don’t know why. But I guess certain things happen for a reason. I remained behind in the U.S., the guys went and did one show in Toronto and another show in Montreal, and they are back, we are back together. I find it funny a bit — in June, I was allowed to get to Vancouver. This time I was told that, “It’s not a habit that you come here with an approved visa, so I can’t allow you.” I didn’t feel good at the beginning, but then I realized certain things happen for reasons. The reason will be known much later. That’s one thing, one last experience, I should say. But within the U.S., I’ve had a good time. And I find that the people that promote these shows and the fans that come to support us, they are very encouraging.