The great Texas-born record producer Bob Johnston, who died in Gallatin, Tenn. in August at 83, is the patron saint of this list, which compiles 50 rock, country, folk and pop albums made in Nashville between 1966 and 2008.

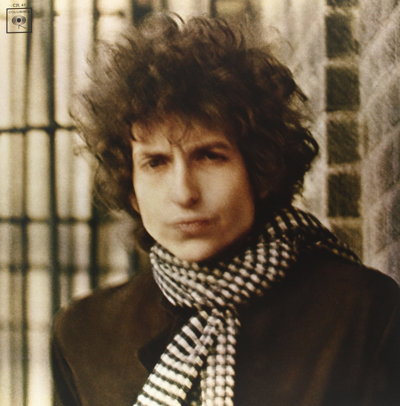

Johnston’s 1966 Nashville sessions with Bob Dylan for the singer’s groundbreaking Blonde on Blonde LP are the starting point for the Country Music Hall of Fame’s current exhibit, Dylan, Cash and the Nashville Cats: A New Music City. And you could say this list serves as a supplement to the Hall of Fame's recent double-disc compilation of music by the artists featured in the exhibit — that collection includes the big names, such as Simon and Garfunkel, Paul McCartney, the Byrds, and Dylan and Cash themselves. This list, however, takes into account many of the less famous (and equally interesting) artists who recorded in Nashville during the '60s, '70s and beyond.

Many of these records feature Dylan-influenced singer- songwriters who came to Nashville to record, but I’ve also picked significant works made by Music City natives whose roots lay in soul, pop and mainstream country. The diversity here suggests that Nashville has been a complex musical melting pot for the better part of the past century — not to mention a city that's produced some very strange records indeed. In almost every way, this confluence of rockers, folkies, soul singers, country crooners and oddball singer-songwriters foreshadowed what is now known as Americana.

Sadly, along with Johnston, several of the famed Nashville session cats who contributed to these records have died in the last year. Guitarist and producer Chip Young and bassist Henry Strzelecki died in December, and keyboardist Bobby Emmons and steel-guitar giant Buddy Emmons died earlier this year.

When I interviewed him in 2012 for the Cream, Johnston offered this chestnut about his days as head of Columbia Records' Nashville division:

They never had me in any fuckin' role. After Dylan did Highway 61 with me, I was in the studio in New York with Dylan, walking around the studio with him, and I got to where the speakers were, and I said, “Dylan, sometime you gotta come to Nashville. They got great musicians down there, and I took all the fuckin' clocks out, and tore the little rooms down where they had everybody workin' with wooden headphones, and put the drums against the wall, and put a 100-foot cord underneath the floor so everybody else could walk around.” Instead of puttin' Dylan in wood, I put him in glass, surrounded him in glass with little levers there, so they could talk to him and see him, and everybody could be together. And Dylan went, “Hmm.” He never answered you, just like Jack Benny. He sticks his thumb on his chin, and when he walked out of there, [Columbia executive] Bill Gallagher and a couple more guys were there, and they walked over and they said, “If you ever mention Dylan and Nashville again, we'll fire you.” And I said, “Why would you do that?” And they said, “Because they're a bunch of stupid goddamn people down there, and we don't want that.”

So, with that in mind, here is part II in this roundup of 50 albums cut in this town or its environs, with the bulk of them recorded before 1981, by which time disco, punk and New Wave had transformed the musical landscape. In some entries, I refer to a song or songs that we couldn't find video or music for, and I hope that will encourage you to seek out the original records. Happy listening! And click

hereto check out part I of this package.

Earl Richards, The Sun Is Shining (On Everybody but Me) (Ace of Hearts, 1973)

While the rest of the pop world was imitating Dylan, Nashville country musicians kept doing their things. Still, The Sun Is Shining reflected some of the changes that had occurred since 1966. “Walking in Teardrops” is essentially Southern rock, while “Mother Nature’s Daughter” begins and ends with a New Orleans piano lick. Bill Wilson, Ever Changing Minstrel (Windfall/Columbia, 1973; Tompkins Square, 2012)

Indiana native Wilson came to Nashville in early 1973 to work with Bob Johnston. Cut with a band that included Mac Gayden, Charlie McCoy and guitarist Charlie Daniels, Ever Changing Minstrel is the Nashville studio system at work—a Dylan fan like everyone else, Wilson wrote songs that reflected a hardscrabble existence, and the band backed him flawlessly. Paul Kelly, Don’t Burn Me (Warner Bros. 1973)

The Florida-born Kelly had scored with 1970‘s “Stealing in the Name of the Lord,” a hit single about the hypocrisy of church leaders. He cut this fine, restrained soul album with producer Buddy Killen and a brace of session players that included Reggie Young. Toni Brown and Terry Garthwaite, Cross-Country (Capitol, 1973)

Recorded at Cinderella Studios in Oct. 1972, Cross-Country features pioneering female rockers in country mode. After cutting three albums as Joy of Cooking, keyboardist Brown and singer Garthwaite traveled to Nashville from their California homes to work with a crew that included bassist Dennis Linde, fiddler Vassar Clements and the ubiquitous Charlie McCoy. “I’ll never forget it — the first time when we laid down tracks, they were just calling out the chord changes,” Brown, who now lives in Northern California, tells the Scene. “They didn’t have any charts or anything. I was like, ‘OK, these guys know everything.’” They created pop-country fusion in songs such as Garthwaite’s “When All Is Said” and Linde’s “I Don’t Want Nobody (‘Ceptin’ You),” which Linde had recorded on his 1970 LP Linde Manor. Toni Brown, Good for You, Too (MCA, 1974)

After cutting Cross-Country, Brown went to Chip Young’s Murfreesboro studio and made a subtle country-pop record. “This was really much funkier,” Brown says of the musicians who played on her second Nashville record. It should have been, since Tommy Cogbill, Reggie Young and Jerry Carrigan added Memphis-to-Nashville grit to such material as Brown’s “Big Trout River,” a song about how families can’t always get along. Bonnie Koloc, You’re Gonna Love Yourself in the Morning (Ovation, 1974)

Another record cut at Quadrafonic Sound Studios, You’re Gonna Love Yourself in the Morning should have been the Iowa-born singer’s breakthrough. Koloc had already cut a series of albums, and came to Nashville at the behest of her label. “I really needed a hit, so the president of Ovation decided that we should go to Nashville,” Koloc, who now lives in Decorah, Iowa, tells the Scene. “They found [producer] David Briggs, and he really knew what he was doing. He was the first one who made the record for my voice.” Koloc’s version of Donnie Fritts’ title track and her own “Roll Me on the Water” are now considered classics. Jack Nitzsche, Jack Nitzsche/Three Piece Suite (Reprise,1974; Rhino, 2003)

Originally set for 1974 release on Reprise Records, Jack Nitzsche was shelved until its release on a limited-edition CD almost 30 years later. Cut at Cinderella Studios, Nitzsche’s solo record featured the former Phil Spector associate and master arranger and producer in Beach Boys mode. The Rhino set includes 1972 demos Nitzsche cut at Quadrafonic, including the incredible “Carly,” about Carly Simon. The Country Cavaleers, Presenting the Country Cavaleers (JBJ, 1974)

This is the most obscure album and group on the list. For more on the long-haired, anti-drug, pro-Jesus Country Cavaleers, see my 2014 Perfect Sound Forever article, interview and discography. Suffice to say, this Florida-bred duo pushed the limits of Beatles-influenced country-pop on Presenting, which was apparently made to sell at their shows. The album's songs are weird country-meets-A Hard Day’s Night hybrids, and “Turn on to Jesus” is Jesus-rock done Everly Brothers’ style. Billy Swan, I Can Help (Monument, 1974)

If anyone on this list exemplifies what made Nashville music great in the ‘70s, it’s Billy Swan. He was the Music City equivalent of Nick Lowe or Ian Gomm — a performer whose subversive tendencies were masked by a seemingly bland exterior. If you haven’t heard Swan’s epochal Sun Records-style title single and its teasing Reggie Young guitar intro by now, I suggest you take a listen immediately. Bergen White, Finale (Private Stock, 1975)

Finale is the only unreleased record on the list, though Private Stock did issue some singles from the sessions that produced it. His version of Dennis Linde and Briane Clarke's "She Won't Let You Down" is great power pop. Linde also wrote the amazing finale to Finale, "Lookout Mountain," a pseudo-Appalachian folk-country-pop song about Confederates and Yankees fighting in 1863. James Talley, Got No Bread, No Milk, No Money, but We Sure Got a Lot of Love (Capitol, 1975)

This record has an immense reputation, and it’s deserved. The Oklahoma-born Talley wrote narratives that described hard times and disaster — ”Give Him Another Bottle” is about a man who has lost everything — but the Western swing-inflected music eased the pain without cheapening his insights. Larry Jon Wilson, New Beginnings (Monument, 1975)

Produced by Rob Galbraith and Bruce Dees, New Beginnings described the travails of being a liberal Southerner in the ‘70s better than perhaps any other record ever made in Nashville. From Augusta, Ga., Wilson wrote about his Southern heritage and the way the outside world — including New York taxi-drivers — failed to understand it. Larry Hosford, a.k.a. Lorenzo (Shelter, 1977)

California singer-songwriter Larry Hosford cut 1976's Cross Words with a group of musicians that included Leon Russell, George Harrison and Moby Grape guitarist Jerry Miller. Hosford recorded part of Cross Words at Mt. Juliet’s Bradley’s Barn with guitarist Billy Sanford, bassists Bob Moore and Tommy Cogbill and drummer Buddy Harman. The followup, a.k.a. Lorenzo, used some of the same musicians at Bradley’s Barn. Hosford’s vocals harked back to the ‘50s and Homer and Jethro. Billy Swan, Billy Swan (Monument, 1976)

Billy Swan is pure pop for now people, Nashville style. Cut at producer Chip Young’s Murfreesboro studio, it’s a masterpiece of absurdist rock ‘n’ roll. As critic Robert Christgau wrote in his review of the record, “The well-meaning optimism and the insecure persona mesh perfectly, and the tunes are pleasurable throughout, whether he stole them from the Sun catalogue or wrote them himself.” Steve Young, Renegade Picker (RCA, 1976)

Although he may be best known for writing “Seven Bridges Road”—the song has been cut by such luminaries as Iain Matthews, The Eagles and Mother Earth — Young recorded this superb country-rock album with Mac Gayden, bassist Michael Leech and steel-guitar virtuoso Buddy Emmons, among others. Mac Gayden, Skyboat (ABC, 1976)

The great Nashville-born guitarist cut his 1972 McGavock Gayden with Bob Johnston, but it has never been released in the United States. Skyboat shows off Gayden’s ability to be both accessible and experimental — the 10-minute “Diamond Mandala” is sort of the Nashville equivalent of a Popol Vuh record from the same time. Jack Clement, All I Want to Do in Life (Elektra, 1978)

No list of Nashville records would be complete without this album by one of the city’s most notable musicians. A masterful songwriter, singer and guitarist, Cowboy Jack Clement was also a futuristic conceptualist, and he anticipated the style of current outlaw country singer Sturgill Simpson on the record‘s“We Must Believe in Magic.” After a long, distinguished career, Clement died in 2013. Scooter Lee, A Louisiana Lady (no label, 1979)

Another obscurity, this one produced by Porter Wagoner. Drummer Jerry Carrigan, steel guitarist Weldon Myrick and pianist Hargus Robbins sound at home with disco on “Ain’t No Need to Rush the Feeling” and “You Don’t Have to Go out Looking Any More.” Copies of this LP go for over $100 these days, but I found it in Nashville for 99 cents. Chance, In Search (Macho, 1981; Paradise of Bachelors, 2013)

The greatest record ever made in Nashville by a former cue-card man for Johnny Cash, In Search is full of frustration. Chance Martin’s liner notes for the 2013 reissue are as entertaining as the record — maybe more, though I like the degraded Average White Band-style funk of “Son of Gunn.” Swamp Dogg, The Mercury Record (unreleased, 1981; S.D.E.G., 2007)

Soul singer, songwriter and producer Jerry Williams Jr. had already contributed to country history with his “She’s All I Got,” which both Nashville-born singer Freddie North and country outlaw Johnny Paycheck had taken into the charts in 1971. As Swamp Dogg, Williams cut a 1981 country record in Music City that remained unreleased until Williams included it on 2007‘s The Excellent Sides of Swamp Dogg, Vol. 5. Joe Simon, Glad You Came My Way (Posse, 1981)

Porter Wagoner’s production of this disco album adds strings, horns and background singers to Simon’s sensuous voice. Bassists Paul Uhrig and Tommy Cogbill anchor the arrangements, and “All Over Me” is prime disco-funk. White Animals, Ecstasy (Dread Beat, 1984)

As I mentioned in my introduction, this list mostly covers 1966 through 1981. I’m not sure what to say about Nashville’s version of New Wave music, but White Animals may have been the best Music City rock band of the ‘80s. Fognode, Beat Hollow (Infrasound Collective, 2001; Beat Hollow, 2014)

Recorded by North Carolina-born drummer and sound manipulator Brian Siskind, Beat Hollow is a trip-hop influenced combination of pastoral guitar, pedal-steel and washes of ambient sound. To my ears, it’s an abstract version of the music Nashville had turned out in the '60s and '70s.

Lone Official, Tuckassee Take (Honest Jon’s, 2006)

The greatest record ever made in Nashville about horse racing, Tuckassee Take combines the approaches of Pavement-influenced indie-rock and old-time Music City practices. Matt Button’s songwriting may have been influenced by Dylan or Lou Reed or Stephen Malkmus, but the record’s beautiful pedal-steel and guitar textures said what his words couldn’t, or wouldn’t. Silver Jews, Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea (Drag City, 2008)

The last record on the list is about words, not music, though the headlong rush of the guitars and drums seems appropriate for its fragmented message. Songwriter and singer David Berman proved himself a lyricist worthy of comparison with Dylan, but the music harked back to The Velvet Underground.