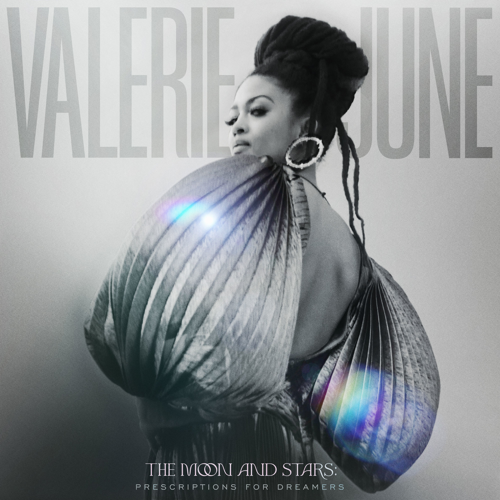

Since her 2013 major label debut Pushin’ Against a Stone and its follow-up The Order of Time in 2017, singer, songwriter and instrumentalist Valerie June has awed fans and critics with her genre-defying, roots-leaning sound, introspective lyrics and otherworldly voice. She broadens her artistic vision on new album The Moon and Stars: Prescriptions for Dreamers, an immersive listening experience that, through complex arrangements and poetic contemplation, offers space for profound healing and reflection.

“It takes wild and ambitious and fearless dreaming to say, ‘What kind of new world can we create? How can it be more holistic? Are there enough resources on the Earth for us to be well-fed and have all of our human rights respected and appreciated?’ ” she tells me. “That’s the kind of healing I’m trying to do through song.”

About a week ahead of the album’s release, I spoke with June about the intersection of songwriting, collaboration and spirituality.

We’re a year into the pandemic now, and there’s so much else that’s gone on over the past year, too. How have you been doing, both with regard to how COVID has affected the music industry, and with all of the other events we’ve lived through?

I was fine at first, until the last few months. I am whipped. I miss everybody. I wasn’t able to go to Christmas. I haven’t been back to Tennessee. … We had to do some work, so we got testing facilities to come on-site so we could do the “Call Me a Fool” video. Everybody was so happy to be in a room with other people. Even socially distanced, we were like, “Yes! I’ve missed you!” And I didn’t even know these people. [Laughs] So I’m starting to get excited.

Last week I got my first shot, and I get my second vaccination in a couple of weeks, so I’ll come to Tennessee like I do in the spring. I’ll start the garden in Humboldt, at my mom’s place where I live there. I’m looking forward to coming to Nashville, going to eat, going to Josephine’s, doing all my normal stuff. I’ll go to Memphis, of course, and hang out with all of my friends there. I live in Brooklyn and I live in Tennessee, and I travel back and forth every couple months. I don’t get to do that now.

It’s hard to engage with any kind of art these days without having the context of the pandemic and current events at least in the back of my mind. I had that experience while listening to your album. Have you had a similar experience? How has that shaped your perspective on the music?

It certainly has and is changing. I find that songs are like that anyway. You could listen to a song that you heard when you fell in love with your first boyfriend or girlfriend or whoever. It comes on randomly in a grocery store now, and it means something different than it did then. So I always say that songs are living, because they change — their messages and meaning change as time goes on.

That’s definitely happened to me with this record. I felt so frustrated last year to have the record done before the pandemic came and to be almost finished mixing, then the pandemic hit and the label said, “No, we’re not going to do it right now.” I felt so sad. I’ve been with some of these songs for 15 years. Others were made while I was touring The Order of Time. We started recording in 2018, and we recorded in 2019 — by 2020, I was ready to roll. But the message then was “pause.” And as I paused, and I did my meditation and did my thing, then the songs started to really speak to me and their purpose and their place, and how timely and amazing it was that it came this year instead of last year.

What needed to happen last year was the 20/20 vision of all the wounds and all the negativity coming to the surface — for us to really be able to see who we are and what kind of demons we’re dealing with in our hearts, and what kind of angels we’re dealing with in our hearts. For all of that to come to surface, that needed to happen. Once the veil is torn, only then can you start to heal. So it’s very timely that the record comes out now, in this place when our hearts are tender.

You’ve mentioned some artists who help you believe that change is possible through music, like John Lennon, Aretha Franklin and Sam Cooke. Considering your own writing process, when you really feel yourself being able to channel your inner hopes and dreams, what does that look like? How do you take what’s inside you and translate it to the page or a recording?

I get so happy when I’m able to do it, because you’re basically working in an invisible world. You’re working in an imaginary realm. I like to live there as much as I can, because it’s just so beautiful and so ethereal and magical, these places where songs and art and poems and stories come from. It’s what could be, you know? Staying in that place and capturing a song, and then bringing it back to Earth and sharing it with other musicians and with an audience of listeners — it’s so joyful to have that experience, even when it’s a song that hits your sad parts or your dark parts. You used the word “catharsis” earlier, and that’s the word when you have a song that comes and it connects with people and it hits their dark side and lets them get that out.

While listening to the album, I really felt like I’d been dropped into a new world that you’d built, in a way I don’t always feel with albums. Was the idea of world-building at play in your process when you were making the album?

One of the things I enjoy doing when I am unpacked from the suitcase and I have some time in New York is going to art exhibits. Sometimes they’ll have these art fairs, and each artist will be given a booth, and they’ll create a world, in that booth, of their art. You walk into this little booth, maybe 10 feet by 10 feet, and somebody has invited you into their world.

When I do that, what I realize is that we all have these worlds. We’re all living in separate worlds within this world. “What is the magic of your world? How can you bring that magic forth and share that with other people to help uplift them?” is the question I asked myself. I wanted to give you a feeling of what it’s like in my world, and what it’s like to go to that place.

You co-produced the album with Jack Splash. What was it about him that made him a good creative collaborator for you?

He joined the band, so he was inside the songs as well as producing them. That was cool to have, but the coolest part was that he was respectful and encouraging me as an artist who’s learning new things about recording. I gotta tell you, I didn’t care anything about recording or technology. … But I started teaching myself that stuff, and to have a master teacher like Jack come into my life was huge. One of the things he discussed with me was an email from the Grammys trying to highlight more female producers. He said: “I really think that needs to happen. What do you think?” But what he did was not just say, “I think that needs to happen,” but he took me and step-by-step taught me how to produce songs.

Both Lester Snell and Carla Thomas appear on the album. Given their rich musical histories, what did they bring to the table creatively that you may not have had access to otherwise?

They brought everything. The album is Lester Snell and Carla Thomas. That, to me, is what it is. That was one of the gifts of working with Jack; he was able to hear my voices and say, “I know exactly who we need to get to do that voice.” So he said, “We have to get Mr. Lester to do the strings and play on your record.” … You meet him and he’s the most humble man and so chill, then you go in and with four musicians he’s able to get a sound that sounds like an orchestra. …

About a month later, I was like, “I gotta get Carla Thomas to sing with me on ‘Call Me a Fool.’ ” I’d heard her on “What a Fool I’ve Been” and had listened to it for years and years. … So she’s the fairy godmother of the record. To work with her and hear her stories was life-changing.