Nashville is so rich with musical achievements that sometimes you have to dig deep to get surprised anymore. And given the heaps of talented musicians, songwriters and producers living and working in and around Middle Tennessee, it’s not uncommon (even during the pandemic) to interact with someone who helped change things up across genres. But you don’t often encounter a titan of electronic music and synth pop. You could say that about the late, great Donna Summer, or formerly local Italodisco icon Trish Vogel of The Flirts. But I’m here to talk about Kim Carnes, who’s been tackling genres with style and grit for five decades now, and how in 1985 she released a historic synth-pop album.

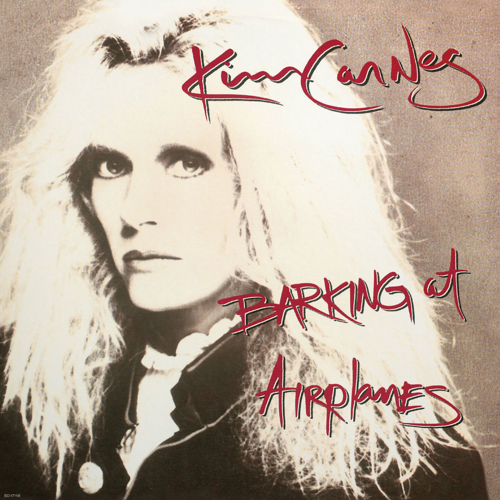

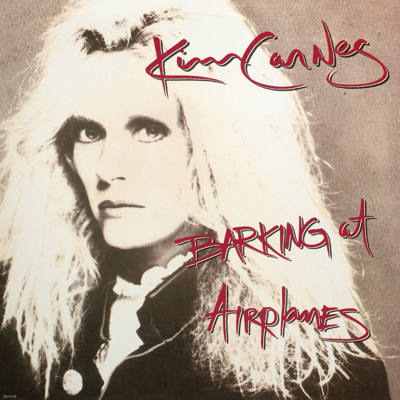

Barking at Airplanes is a distinctive record. Released right smack in the middle of the ’80s, it bridges the expansive variety of sound proliferating throughout the world at that time. It’s smooth like SoCal yacht rock, angular like Italy’s most left-field club struts, majestic with the operatic punch of lighter-swaying Detroit arena rock, icy-hot passionate like the sonic onslaught of Trevor Horn’s Zang Tuum Tumb empire, and rooted deeply in the kind of emotional truths that Carnes had been serving up as a songwriter and solo artist since the ’70s. This album distills a seemingly impossible collection of sonic movements, meshing the acoustic and the electronic in a way that still thrills.

Great pop albums were plentiful in the ’80s. That decade was certainly the zenith of synth-pop as a genre, though it endures to this day in countless subgenres and magpie-philosophy hits. But Barking at Airplanes was the first widely distributed synth-pop record produced by a woman, and though Carnes’ place in music history as a songwriter and artist has been secure for quite some time, it’s the historic nature of this record (and its recent 35th anniversary) that led me to talk with her. For an hour on a lovely, quarantined Monday afternoon, I spoke on the phone with Carnes about one of the greatest albums ever recorded, and it was everything any fan of electronic pop could hope for.

Was there ever a point when Barking at Airplanes was going to be a concept album? There are moments where there’s not a traditional narrative, but elements of the songs are echoed in others. Like the way that the Wall of Men background vocals in the last choruses of “Crazy in the Night” and “Don’t Pick Up the Phone” seem to dialogue with one another. Or how the ethereal vocal pads and chords on “Orpheus” and “Oliver” seem to be syncing through time with “Draw of the Cards.”

Not consciously, no. I wasn’t thinking that they should fit in that way, but because I write the way I do — I write mostly on piano, unless I’m with someone else who plays guitar — a lot of those chords, I steal from myself. I always have pictured the things that I want to do in a song, how I want to tell that story. Like on “Bon Voyage,” I asked someone at the EMI offices in Paris if they would take a recorder to Charles de Gaulle Airport and record the tone and announcements there, because I knew that that song was situated in that space, and I wanted that atmosphere to begin and end the song. There are so many songs that as I write them, I picture little movies in my head. And while the whole album wasn’t meant to be a grand conceptual story, each of its pieces were these little movies, and that kind of fits that category. And you mentioned “Oliver,” and when I wrote that I thought it needed a shortwave radio and not tuned to a channel, just picking up the space in between — the static. [Co-producer Bill Cuomo] is so creative, and so keyed-in, that any of my ideas and flourishes to help tell the stories in those songs, he was all for it and helped to make it happen.

That’s the best kind of collaborator to have — someone who takes what you give them and can run with it.

Yes! He had been my keyboard player for many years, starting in my early days, playing on the demos I would cut for other artists. And he was so incredible, we just hit it off immediately. I still refer to him as my right and left hand. I can write something, play it on the piano, and he’ll watch me play it a couple of times, and then sit down with it. You can’t really teach somebody — they can copy your chords, but you can’t teach them the same feel. But Bill just knows. He’s been so instrumental in so many of my albums that it was time to work together on that level.

One of the things about this record that feels so historic is that it’s the first synth-pop album produced by a woman, and you don’t get enough credit for that. That’s a landmark.

I don’t get any credit for it. You’re the first person who’s ever pointed that out — or noticed, even, I should say. … We took great care with it, and somehow it all just got lost, except for “Crazy in the Night.” When that single was a hit, worldwide, I would go to Europe and to South America and do shows there and do “Crazy in the Night,” and the sense of potential was so great. And I thought, “This is how ‘Bon Voyage’ and ‘Rough Edges’ and ‘Oliver’ — this is how these songs are going to get out there and they’ll get heard, and they’ll get noticed.” And not really. The album didn’t get dug into very deeply.

So much of your work in the early ’80s found a way to bridge the rock world and the more electronic sounds coming out of Europe. There’s never a sense that any aspects of the record are in conflict with each other.

I was always so taken by some of the synth sounds coming out in those days, just obsessed with it. And the Fritz Lang movie Metropolis. That film blew me away, and I must have seen it again and again. The film Black Orpheus as well — all those gorgeous, hypnotic elements, mixing together and making something beautiful. Early on, Bill had a Prophet synthesizer, and just the warmth of that machine, that analog keyboard. When I wrote songs on my acoustic piano, I knew, in my brain, I could hear it as played on that synth. So there had to be that collaboration in all of the elements.

Did y’all record analog or digital?

I couldn’t tell you for sure. Probably analog, just because I held on to that as long as I could. I love analog. For some artists, digital is the way to go. But for me, the warmth of analog always won out. And even albums that I recorded digitally, I would mix them to analog, just to recover some of the warmth. I always loved the sound of The Cars’ albums. And Mike Shipley, who engineered and mixed all those albums, we put a call out to him and he said he would come and mix [Barking at Airplanes]. That was an important part of that record, because we had all the sounds down, and all the songs. But it can all be ruined, or lost, in the mix.

I’ll never turn an album over to an engineer and say, “OK, mix this, and I’ll come back.” I have to sit there the whole time. I’ve always said it’s like having somebody else dress your baby. As we were writing these songs and recording everything, I heard it all in my head, and what you want is for that to continue on. I wanted to bring Mike’s expertise on, and use that to keep the sounds that Bill and I had brought, to understand what we were going after. He was an important part of the album, for sure.

While you were writing, was it a conscious process of, ‘This needs to be synthetic, but this needs to be live?’ Do you have those arrangements in your head as well, or is that part of the development process as you bounce sounds off of different people?

I’d say it’s a little of both. I would have arrangements in my head, and Bill would too, but there would be a lot of brilliance coming from my band, from the guys playing. I always want to see what they’re going to come up with as well. You pick people, and you have them around you because you know that they can come up with something amazing that hadn’t occurred to me.

I know when something’s wrong, but I also know when it’s right. Like on “Rough Edges,” Ry Cooder plays the most amazing bottleneck guitar, which is his style, and I am such a huge fan of his, and I thought, ‘We’ve got to have this on the record.’ And I could never have thought of the notes he’d play; he just came in and was his brilliant self. And also on that song, the backing choir, these were all people I love and respect, James Ingram, Martha Davis from The Motels, Julia and Maxine Waters — people whose voices are just amazing and that I remain in awe of.

With you mentioning James Ingram, I want to jump back in time a year to “What About Me,” because that song is incredible. In musical theater and Broadway, they do trios all the time, but I can’t think of another pop song, before or since, that’s a trio with three distinct voices and has a narrative to it.

That’s not to say there isn’t another, but I can’t think of one. The song “Make No Mistake (He’s Mine)” that I wrote, it wasn’t necessarily written for a trio to sing, but it was meant to represent the three sides of a love triangle — so it could have been a trio, but worked out best as a duet.

Your solo version of it pops up as one of the bonus tracks on the 2001 remaster of Barking at Airplanes. Put that with the famous duet version between you and Streisand, and a potential trio take on it as well; that’s covering a lot of ground.

Wait. I didn’t even know that. That version of “Make No Mistake” is a demo. Once I had written the song, I went in and recorded it to send to Barbra to prepare for us recording the duet, and that’s all that that take was meant for. It’s weird that that’s there.

Yeah, this is the 2001 CD from One Way/EMI Special Markets, with three extra tracks — it’s got “Forever,” the solo vocal version of “Make No Mistake,” and a cover of Yes’ “Into the Lens,” aka “I Am a Camera.”

OK, so “I Am a Camera” was an outtake, and we didn’t really like it. I love the song, and I love the original version, but when I tried to sing it I thought it was terrible. So I learned a lesson, which is if you’re recording for a record label and you don’t want something to come out, erase it. Never did I dream that they’d put that out. That was not supposed to be on there.

I think it’s incredible. I have a friend who is a huge prog fan, one of those folks who you can tell when he’s had too much to drink because he puts on The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway.

[Carnes laughs]

I played your version of “I Am a Camera” for him because he’s a huge Yes fan, and he declared, “This is better than Yes’ version.” So take that as a compliment.

I do, but I love that song, and I wanted to like my version of it, but it was not for me. Again, lesson learned. Surprise for me.

Check out a supplemental playlist featuring instrument demonstrations, film ephemera and more tracks from Carnes that came up in the conversation.

I really dig how both sides of this album kick off with beautiful paranoid dancefloor freakouts coming from completely different emotional spaces. “Crazy in the Night” is a great exemplifier of operatic ’80s first-person rock paranoia. “Don’t Pick Up the Phone,” while it’s coming from just as emotionally fraught a place and is a first-person narrative, it’s more external because the subject of the song isn’t the singer.

Well, part of that is because of inspiration. “Crazy in the Night” came from my oldest son Collin, who was just a little boy at the time. He was having nightmares and when I asked what they were about, he replied "Monsters in the closet, and under my bed!" I quickly wrote that song. It’s his voice saying "who is it" at the beginning of the record. And I wrote “Don’t Pick up the Phone (Pick up the Phone)” about a friend of mine. There’s a similar sound to those two because I had an old Solina String ARP, and those were written on that, which is ancient but was its own really special sound. There’s a song on my Voyeur album, “Take It On the Chin,” that was also String ARP-composed, and when something needs that particular sound, there’s nothing else that compares.

There are newer machines that can emulate those sounds, but it’s never quite the same. The right sound is like a magic spell. Like on “One Kiss,” the way you have that detuned Linn LM-1 side stick-and-clap combo on the 4 — it’s like a millisecond rendezvous with the Minneapolis sound. When you hear that sound, it’s like being transported in space and time. That’s why you can’t go wrong with an LM-1, and why you still hear them on records even today.

I want to ask you about the preponderance of parenthetical titles on the album, because half of the tracks have them. And that’s very ahead of its time.

It’s part of the process — I’m writing the song, and I’ve got the title, but there’s the other aspect that should also be part of it. I love parenthetical titles, and you can tell. Sometimes it’s an afterthought, but more often it’s a situation where “This is the title, but this also could have been the title.”

You mentioned earlier about finding these cinematic spaces as you write. “Oliver (Voice on the Radio)” is such a beautiful and simple concept, but it feels cosmic. It’s not just a declaration being heard across a desolate landscape. It feels like a requiem for humanity, like something in a science fiction movie. Like in Alien (and Alien3), where the last thing you hear is this ship’s log that Sigourney Weaver’s character has recorded. And it carries this incredible heft because it’s the last testament of this group of people, and it travels across the universe, eternally patient on radio waves.

The concept of hearing a voice on the radio is one that any human being from the past century can relate to on some level, but it’s beyond us and it has the capacity to outlast us. With the internet now, anything can be anywhere at all times. It doesn’t have that special, fortunate moment that comes from being in exactly the right physical place at the exact right time to hear this.

When you mentioned Sigourney Weaver — I just saw it all in my brain. I wanted that song to have a kind of mystery, a sense of being unheard, of not coming through — trying to express emotions as directly as possible, but we’re on different channels.

It commemorates itself, like the Percy Shelley poem about Ozymandias. It’s a memory of something that might have happened long ago, and it’s not immediate in any way that you can visually verify. But it feels immediate because the emotions are so strong. And that’s a hell of a way to close a record.