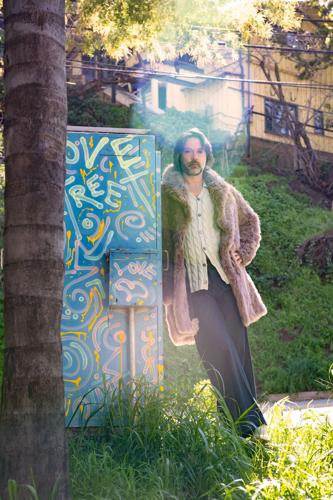

Rufus Wainwright

There simply aren’t very many artists or voices like Rufus Wainwright. One of those polymath talents who build upon multigenerational musicianship and a voracious mind for knowledge, art and the historical sense of the swoon, he’s been making unconventional work that surprises, seduces and shakes up listeners the world over since his 1998 debut. A gifted composer and performer who nimbly shifts genre and idiom, Wainwright is gearing up to release I’m a Stranger Here Myself, which pays tribute to the songs of legendary stage composer Kurt Weill. And so, on a pleasant autumn evening a few weeks before his two shows at City Winery (which happen to be on release day), Wainwright spoke with the Scene via a delightful Zoom conversation, edited here for length and clarity.

What’s it like to sing the national anthem at the World Series?

It was very meaningful for me to be part of the zeitgeist. It was very captivating — you see all the people and the players, and you’re in Los Angeles and it’s sunny, and then all of a sudden you’re at the center of the universe. It was intoxicating.

When you performed at Big Ears Music Festival back in March, you mentioned bringing your duet partner Amber Martin to Nashville to do some writing. Inquiring minds would love to know how that went.

She had never been to Nashville before, so for her it was like a pilgrimage for the Holy Grail.

I’m bound by civic pride to ask, what does Nashville mean to you?

It’s a place I’ve known about all my life, mainly because of Emmylou Harris, who is a dear, dear family friend who always used to come up and visit us in Montreal to write with [my mom Kate McGarrigle and my aunt Anna McGarrigle], or they would go to Nashville to write as well, so there were these songs that tied my family’s life to Nashville. And it was mythic, the stories that came from it. And the other thing that my mother loved about Nashville — she and Anna were successful songwriters to a point, but they never quite broke through to the big time like their friends Bonnie Raitt or Bette Midler. But whenever they went to Nashville, everybody knew who they were. People knew their material and their abilities, and for my mom, that was very heartening — to go there and find themselves respected by that crowd.

Nashville does still have some degree of respect for songwriters. And Emmylou Harris is like Moses: You see that steely hair and crowds just part and make way. Who’s at the top of your dream duet partner list these days?

Well, I’ve been texting quite a bit with Annie Lennox, who I grew up listening to, and we’ve been texting back and forth about a little something lately. The way that’s come full circle is really quite astounding to me.

As a Canadian-American artist, how are you feeling these days about all this — the profound social and political mess?

I was born in the U.S., in upstate New York, and then moved to Canada when I was 6 with my mother, who was Canadian, and that’s where I grew up. I’m a dual citizen, and I feel very fortunate to have — I’m not going to say “that exit plan,” but that state of being in case things head south. But also, and maybe it’s my American side or maybe it’s my Canadian side — we’re fighters, and we don’t really like to simmer down. So there is a lot to be said for staying here and trying to combat the forces that be, because that is important. But also the fact that I can run away if need be, that makes it important that I stay while I can and advocate for those who have no voice or access to power and can just be carted off, which is horrifying.

Rufus Wainwright

What made you want to focus an entire album on Kurt Weill’s music?

Like many interesting projects, it was totally unplanned and came out of nowhere. I was finishing producing a musical in London [Opening Night], and finishing a composition of the Dream Requiem, and it was taking up all of my time. But Christopher Walden of the Pacific Jazz Orchestra asked me if I wanted to do a concert with them, and for some weird reason, likely exhaustion, I said sure. And I knew a lot of Kurt Weill songs, so I said, “Let’s do a Kurt Weill evening.” And lo and behold, in the midst of all of this I flew to L.A. and rehearsed with the orchestra for a day — the day of the show, did the show that night and recorded it, and the next day headed back to England.

We thought it might be nice to save and preserve some of the madness. But there was something in the frantic nature of the whole thing, and how Weill sounds better when you’re a little tired. … You can’t be perky with his work. And this dark texture to the material, when we listened back to it, we thought this could make a captivating record. I think the songs speak to the time we’re in. You find Weill resurgences every 30 or so years, and I remember in the ’90s there was the show that Hal Willner put on with Marianne Faithfull.

I got to see that! The 1995 Weimar Cabaret afternoon at BAM where she performed most of Seven Deadly Sins. It was transformative.

I just like to think that we’re part of this latest cycle, as it happens in history.

I was told to ask what your beard regimen is these days, because it’s an inspirational look.

I’m actually searching for a barber that I had years ago. I was staying in this town in France where they did coronations back in the day, and this barber gave me a perfect beard cut, and then the next time I found myself there I couldn’t find him. It was like the barber shop had just disappeared into the air. This ghost of a barber.

You found a barber shop like Brigadoon.

[Laughs]