Lori McKenna was talking on the phone last year with her producer Dave Cobb, rehashing the old complaints about the treatment of female artists by country radio. Women, they agreed, bear the responsibility for tackling the touchy subjects, but rarely are they rewarded for taking those risks. Just like women in families.

“I was thinking about that conversation while I was driving my daughter to school the next day,” McKenna remembers. “I was thinking that storms and sailing ships have names, and often they’re women. The thought occurred to me, ‘What if a town had a gender, what else could it be but a woman?’ Like a mother, a town raises you up to go off and pursue your dream, and if it doesn’t work out, the town will welcome you back.”

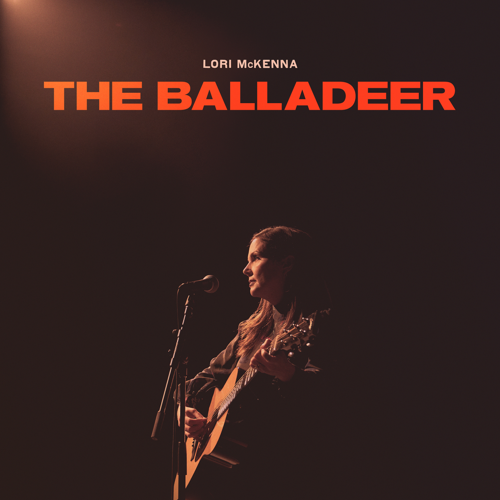

Not everyone’s mind works like that, but McKenna’s does. That chain of thoughts led her to a song called “This Town Is a Woman,” the lead track on this year’s The Balladeer, her third straight album produced by the ubiquitous Cobb. “The way you talk is partly her fault,” McKenna sings over an acoustic-guitar strum that lands halfway between her folk music roots and the country music world in which she’s won so many awards. “She knows you’ll leave ’cause they always do,” she adds on the piano-reinforced chorus. “She’ll wish you well and wait for you right here.”

The lyrics don’t specify a particular town or region — although they mention a freeway and a sugarcane field — but the two crucial towns in McKenna’s life have been her hometown of Stoughton, Mass., and her adopted town of Nashville. Although her primary residence is still Stoughton (pronounced “STOE-ten”), for years she has been coming to Nashville twice a month to practice her profession. In the fall, she finally bought a townhouse here. But her work has been put on hold by the coronavirus, and she’s staying in Stoughton for the present.

“I’ve never really lived in Nashville,” she says, “so I have this magical sense of the city. I love the idea that at any moment, a great song is being written somewhere in town. When I could, before the pandemic, I went every other week, first flight out on Monday and last flight home on Wednesday. Two of our kids, my oldest Brian and third-oldest Chris, are living over in East Nashville, writing a song a day or two songs a day. I miss Nashville.”

But Stoughton is still home. That’s where she married Gene McKenna as a teenager and raised five kids. She married early and found her career late. She didn’t perform in public till she was 27, but when she did, she was quickly embraced by Boston’s lively folk music scene. Fellow performers such as Mary Gauthier recognized that McKenna’s songs could vividly evoke a scene and make the listener feel the characters’ joy and pain. And because McKenna had already been married for eight years when she started playing out, the songs’ characters were usually married, too.

If rock ’n’ roll is music for dating, country was once music for marriage. That’s not as true as it used to be, and as a result, the need for good marriage songs is more dire than ever, especially in the mainstream. Both stages of romance are important, but the music industry has overemphasized the former at the expense of the latter. As a result, McKenna’s songs were more valuable than ever — especially in Nashville, where the tradition of country music as marriage music needed a revival.

“Maybe it’s because I’ve been married for so long,” she says, “but there’s a lot more going on in those adult relationships. I like talking about difficult things that turn out OK, about the way your failures get you to your next step. ‘Good Fight,’ another song on the new album, is like that. I’m not a person who likes confrontation — I’ll avoid it at all costs — but I’ve come to realize that we’ve grown the most from things that were really hard, when we didn’t know if we were going to make it through to the next step.”

“Don’t try to kiss me yet,” the song’s narrator says to her husband after a quarrel, “ ’cause I ain’t over it.” Over the chunky, catchy country-rock of the band, McKenna adds, “Whatever you do, don’t make me laugh, ’cause you ain’t gonna win.”

“Good Fight” plays on the double meaning of its title, which can refer to either a fight for a good cause or to a fight fairly fought. McKenna means it both ways: a fight to keep a marriage going and a fight fought to find common ground, not to score points. It’s one of two songs on the new album that she co-wrote with Liz Rose and Hillary Lindsey. (McKenna wrote the other eight by herself.) The three women have written so many hits together that they call themselves The Love Junkies.

“Liz has grandchildren; [my children] are starting to leave home, and Hillary’s daughter is 4,” says McKenna. “So we’re at different stages of our lives as mothers, as partners. But certain interactions are universal, even if we each bring our own perspective. That’s the best way to write a song: approaching the same experience from three different angles.”

The Love Junkies have written such hits as “Girl Crush” for Little Big Town, “It All Comes Out in the Wash” for Miranda Lambert and “Cry Pretty” for Carrie Underwood. Without Rose and Lindsey, McKenna has written such hits as “Humble and Kind” for Tim McGraw, “God and Country” for George Strait and “Fireflies” for Faith Hill.

It was Hill who unlocked the door to Nashville for McKenna. When producer Byron Gallimore played a McKenna demo for Hill in 2004, the singer was so impressed that she asked to hear everything the songwriter had ever written. Hill ended up using three McKenna songs on 2005’s Fireflies, including the title track and the single “Stealing Kisses.” After that, McKenna left the open-mic nights at folk clubs behind and started making regular trips to Nashville.

“I love the language that country music speaks,” McKenna says. “It’s very descriptive — less poetic perhaps than folk music, but maybe more profound. I love the stories about ordinary people’s lives. I love those songs that pull apart those little details. I love that moment in a country song when you go, ‘That’s exactly how I would say it if I were at that table in that moment of crisis.’ ”

If mainstream radio focuses on the dialogues between young lovers and shortchanges the conversations between spouses, radio is even stingier when it comes to the conversations between siblings and between parents and children. Once again McKenna addresses that imbalance on the new record by offering a sibling-to-sibling song, a child-to-parent song and two parent-to-child songs. The message of the two latter numbers is pretty obvious from the titles, “When You’re My Age” and “ ’Till You’re Grown,” but the tone is less, “Then you’ll thank me,” and more, “It’ll be OK, because it happened to me too.”

“The Dream” is an ingenious fantasy in which the narrator imagines the father who died before her wedding finally getting to meet her husband in a dreamworld. In reality, it was McKenna’s mother who died when she was a child, but the gender switch works when the father tells the husband a story: “Using his hands to mark out something / Maybe the size of his love / He never really spelled that out / When he was down here on the ground.”

The new album’s highlight is “Marie,” named for McKenna’s sister, who is older by four years. Like many of the songs on the new album, this one takes on a hymn-like quality, thanks to Philip Towns’ churchy piano. McKenna acknowledges all the ways the two sisters are different, and how much that matters when you’re young. But the singer concludes: “She knows bigger words than I do / But we both got the same size shoes / And no one’s ever walked in mine / But me and Marie.”

“She was always right there when I needed her,” McKenna says quietly. “We have different perspectives on our own childhood and on our dad, the man who raised both of us. We may not agree with the other’s interpretation, but we’ve listened enough that we understand it.”

In September, as part of AmericanaFest, McKenna played a showcase at the Anchor Fellowship, a church on Third Avenue South. Backed by a four-piece band led by guitarist Mark Erelli and strumming her own acoustic guitar, McKenna wore a black vinyl skirt with her brown hair rolling over the shoulders of her pink-print blouse. She sang some of the hits she wrote for country stars — “Stealing Kisses,” “Humble and Kind” and “Girl Crush ” — but she also sang “People Get Old” from her 2018 album The Tree.

Two nights earlier at the Ryman, she performed the song during the Americana Honors and Awards ceremony — it was a nominee for Song of the Year. She also previewed “When You’re My Age” from this year’s album. She had hoped to be playing that song at many a live show this summer, but the coronavirus had other plans. So now she’s stuck in Massachusetts, performing less but writing more. She is set to play a livestream on Friday, marking The Balladeer’s release and supporting Club Passim, a nonprofit venue in Cambridge, Mass.

At the Anchor, after she’d finished singing “The Bird and the Rifle,” the title song of her 2016 album, she told a joke. It’s as revealing as it is funny: “My kids always ask me, ‘Why do you only write sad songs?’ ‘Because of the rhymes,’ I tell them. ‘Only sad words rhyme.’ ”