Author’s note: Last week, I had the distinct pleasure of letting David Berman into my head for a whole day. I woke up early to write a preview of Purple Mountains, the new self-titled album by Berman’s new project. I spent the entire day wrestling with a profound record from one of my favorite writers — one of the indie-rock scene’s most complicated minds. I came away from the experience with hope for the future. I hoped that Berman was about to make the big crossover, to finally achieve the grander recognition and success that his work deserved.

I turned in the piece (on time for once), went for a walk with my son and came back to discover that Berman had passed. It was disorienting and overwhelming and bizarre. My friends are evenly split between writers and musicians (often a little of both), and to see the effect that Berman’s work had on so many of us was beautiful and sad. I didn’t know David very well, but he was a presence, an influence and guiding light, a friend of friends and a pillar of my record collection.

Back in 2006, when my friends and I were running Grand Palace Records in Murfreesboro, Berman would come into the store. He was in the early stages of sobriety and had joined the Big Brothers program, mentoring some wayward kid from Rutherford County. It was an awkward pairing: David, tall and erudite; the kid short, scrappy and, well, very Rutherford County. David walked this young ruffian through our tiny store, explaining the history of rock ’n’ roll with more kindness and patience than anyone has ever used to explain anything in a record store.

Eventually, he landed on Dinosaur Jr.’s You’re Living All Over Me, explaining the record’s impact with elegance and affection. And then he bought the kid the record, even though the kid didn’t have a turntable. He said something to the effect of: "You’ll have it when you need it." This is the David Berman that I hear when I listen to Purple Mountains: A kind, beautiful soul that had a lot of wisdom to share, a clever mind with humanity to spare. He will be missed.

Read the full feature story below.

It had been a while since I’d had a good, hard cry — the sort that sneaks up on you and smothers you with a blanket of emotion. I’d been stiff-upper-lipping my way through some pretty heavy life changes when I heard David Berman sing: “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion.” And I fucking lost it. Barely a verse into Berman’s new project’s new self-titled album, I realized that I was not prepared to deal with the new Berman, and I was not ready to engage with Purple Mountains, a true masterpiece.

This was a total surprise. It had been more than a decade since Berman’s former band Silver Jews had released a new record, and Berman’s writing had the depth and profundity to endure during those years while the artist himself disappeared from public life with only the merest of traces. The Jews’ ’90s records American Water and The Natural Bridge were essential indie artifacts, slices of intentionally obtuse American art that encapsulated intellectual life in the post-Cold War afterglow. The Jews’ records from the Aughts are essential documents of pre-It City Nashville, before the flood and all the bachelorette parties that washed up on these shores afterward. Hell, “Punks in the Beerlight” could have been the Springwater anthem during Dubya’s second term.

Silver Jews wasn’t anything close to the biggest band in the world, but for the time between 2005’s Tanglewood Numbers and the group’s 2008 swan song Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, they were the biggest indie band in our neck of the woods. For me, a small-town kid who had to go to great lengths to find those early SJ records, living in the same area code as Berman was enough to prove that somewhere amid all my bad decisions, I had made at least one good one. “Living among poets” isn’t a life goal you’d tell your guidance counselor about, but it was a romantic ideal that made the bouts of underemployment all the more palatable. And when the Jews played their final show at Cumberland Caverns in 2009, a chapter in this city’s artistic evolution closed.

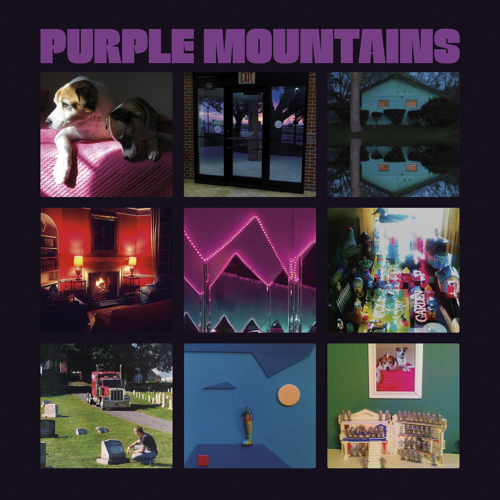

Fast-forward to 2019: After a decade of being off the radar, Berman began to resurface. An interview here, an album announcement there, a music video for the heartrending “All My Happiness Is Gone” — these were the first signs in years that Berman hadn’t been wholly consumed by the addiction or the depression he had struggled with for years. The Silver Jews moniker, an awkward one for sure, was gone. In its place: Purple Mountains. It is striking, heavy and maybe a little foreboding, yet it implies a majesty that is completely missing from the often-self-deprecating Silver Jews. After such a prolonged silence, it seemed like a radical change in direction.

Provided to YouTube by Drag City Records

Snow is Falling in Manhattan · Purple Mountains

Purple Mountains

℗ Drag City Inc.

Released on: 2019-07-12

Auto-generated by YouTube.

On the album, Berman comes across as a writer renewed. “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan” is the sort of song that Nashville ought to always aspire to — it is on a level with Mickey motherfucking Newbury at his very best. “Snow Is Falling in Manhattan” lingers on the little details, leaving plot and conflict aside and illuminating meaning through intimate sketches of scenes flush with humanity. It is a fully formed short story that stands alongside the year’s best. Beautifully orchestrated and masterfully performed, “Snow Is Falling” is elegant and emotive in a subtle and supple manner. And it is par for the course with Purple Mountains.

Berman’s growth as a writer is so tremendous it is easy to miss. There are plenty of top-notch Silver Jews songs, but some of their lyrical turns look painfully clever in comparison. Berman has taken a turn for the clear and concise without losing any of his wit or candor. In “That’s Just the Way That I Feel,” the “playing chicken with oblivion” song, Berman uses the word “schadenfreude” once, and then uses it again to make fun of its first use. The dude's still got it! But more than jokes and triple entendres, Berman has dipped his pen in a well of what Don Delillo might call “small dull smears of meditative panic.” That elevates Purple Mountains beyond any sort of esoteric niche. Purple Mountains is accessible and relatable in a way that Berman’s work has never been before — and hopefully just an inkling of what the future holds.