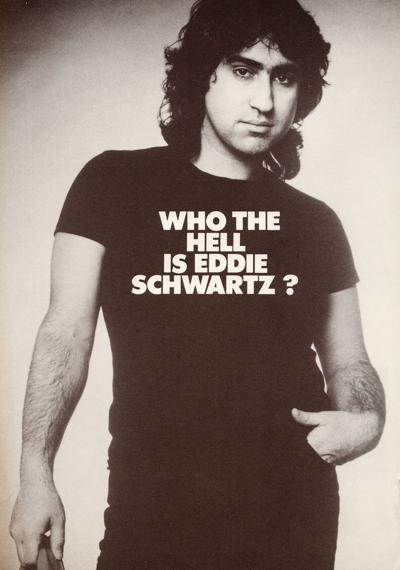

Atlantic Records promo shot from 1981

You may not know Eddie Schwartz’s name, but you certainly know his work. Born and raised in Toronto, Schwartz became a well-regarded recording artist north of the border in the early 1980s, and has had even greater success as a producer and songwriter, with writing credits that include Paul Carrack’s “Don’t Shed a Tear” and The Doobie Brothers’ “The Doctor,” not to mention cuts by America, Joe Cocker, Donna Summer, Rascal Flatts and Rita Coolidge. But his first (and biggest) hit, Pat Benatar’s “Hit Me With Your Best Shot,” very nearly wound up on the dustheap of musical history.

Over a recent lunch at the fabulous Frankie’s 925 Spuntino, Schwartz, who has lived in Nashville since 1997, shared the wild tale of one of the most defining hits of the 1980s. (Disclosure: He’s a friend of mine.)

When Schwartz arrives in Los Angeles in late 1978, he has good reason to be excited. The young singer and songwriter has just inked a deal with ATV, the same publishing company that is home to The Beatles’ catalog.

But the meetings at ATV don’t go exactly as he hoped. The president and vice president love four tracks from the bare-bones five-song demo he brought along. But when it comes to Schwartz’s favorite tune, “Hit Me With Your Best Shot,” they don’t mince words.

“‘We think it’s beneath you as a writer,’” Schwartz remembers them saying. “‘That may be the worst song we’ve ever heard.’”

Schwartz had written “Hit Me With Your Best Shot” at a low point. He was in his mid-20s and felt like his music career was going nowhere. Feeling utterly despondent, he decided to see a therapist a friend had recommended.

“It was this sort of experimental therapy, and one of the things we did was punch pillows,” Schwartz recalls. “So after a session where I punched a lot of pillows — to get out hostility, anxiety, whatever — I walked out on the porch of the place. The phrase ‘Hit me with your best shot’ just came to me, and I thought, ‘There’s something there.’”

So he jotted it down in a notebook. It would be a couple years before he wrote the song — while taking college courses, he pulled out that notebook and happened upon the phrase.

“Writing the song was an act of defiance against … the music business that seemed to have no place for me,” Schwartz says. “The ‘tough cookie,’ you could argue, is the music business, because that’s who I was wrangling with, and so far, not winning any battles. … I think the breakthrough I had was understanding that I can wrap this idea in what appears to be a song about the battle of the sexes.”

After his meeting at ATV, Schwartz stays in Los Angeles for a few months to write. Much of that time is spent begging ATV to let him make a proper “Hit Me” demo. Eventually, just to shut him up, they relent. He has a friend playing with Elton John who brings in some of his bandmates.

“It was this little studio in Hollywood, owned and operated by a guy named John Rhys,” Schwartz says. “One of the guys from ATV was there as the producer, supervisor. We listened back to the demo, and he turned to John and said, ‘Erase it.’ I had spent all this time begging to get this demo, and this guy says, ‘Yeah, I hate it. I still think it’s one of the worst songs I’ve ever heard.’ He thought it would reflect badly on them if it got out. … Now, we recorded it on 2-inch 24-track tapes, so my despondency went to a whole new level.”

Feeling defeated, Schwartz books a flight back to Toronto for the next morning.

“I was packing my stuff,” he says, “and the phone rings in the apartment. ‘Hi, this is John Rhys, the engineer on the session. … Listen, I want you to come over for dinner tonight.’”

“It was amazing, like a gumbo kind of thing,” Schwartz recalls. “And we sat outside on this little balcony overlooking Hollywood, and he reaches into his breast pocket, takes out a cassette and puts it in my pocket, and says, ‘I had to erase the tape because ATV’s one of my biggest clients. But before I did, I made one copy of it. You can’t play it for anybody now, because they’d fire me, but there will come a time and a place.’”

Schwartz flies back to Toronto the next day, dejected. About six months later, the phone rings, and it’s Marv Goodman, who has just been hired to work at ATV’s new office in New York. He likes Schwartz’s work and asks if there’s anything he hasn’t heard yet.

“And ‘bing,’ this little bell rang in my head,” says Schwartz, “and I said, ‘Well, I’ve got this one song. Everybody hates it, but I think it’s pretty good. Can I send it?’ I couldn’t afford to make a copy. … So I put the one existing cassette in a padded envelope and sent it down.”

When the tape arrives, Goodman still has two weeks left at Chrysalis Records before he starts at ATV. Schwartz isn’t present, but he recalls the scene as Goodman described it to him.

“He put it in his cassette player in his office at Chrysalis, and started playing it,” Schwartz says. “And he loved it, and he kept turning it up, playing it over and over. Pat Benatar was having a meeting with her A&R guy at Chrysalis, Jeff Aldrich. She didn’t really like any of the stuff he was playing her, and then she started hearing ‘Hit Me’ through the wall. Marv was in the next office, and she got up and went into his office and said, ‘What’s that?’’

Benatar recorded the song for her album Crimes of Passion, released in August 1980. Schwartz was thrilled to have a cut, but when he heard the album, “Hit Me” sounded nothing like he had envisioned. To him it was a defiant, tongue-in-cheek tale about the harsh realities of the music biz machine. “But she turned it into a big rock anthem,” Schwartz says. He wasn’t sure what to think about it. And he’d been beaten up by the industry enough that he didn’t have any expectations.

It’s not until early spring 1981 that he first hears it on the radio, and begins to realize it’s a massive radio hit. He’s strolling down Yonge Street, a bustling Toronto thoroughfare. It’s an unseasonably warm day, and businesses have their doors propped open. As he passes House of Lords — a renowned salon that styled hair for the likes of David Bowie, Axl Rose and Kiefer Sutherland — a song blasting from the salon’s speakers stops him in his tracks.

“I’m standing there in the doorway,” Schwartz recalls, “and I think I started to drool. … There’s these two rows of barber chairs, and there’s a guy looking very mod at the back — on the phone, pointing at me and having a very animated conversation. He puts down the phone, and I’m still standing there, sort of in a state of shock.”

Apparently, Schwartz’s peculiar behavior prompted the salon worker to call the police.

“I feel a tap on my shoulder and turn around,” Schwartz says. “There’s two cops, and they said, ‘Come on, buddy, move along.’ And I went, “No, no, they just played my song!’ And the guy looked at me and said, ‘Yeah, sure they did. Tell your story walking,’ that kind of thing. That’s the first time I heard it on the radio.”

And it was all thanks to pillow-punching therapy and a prescient recording engineer named John Rhys.