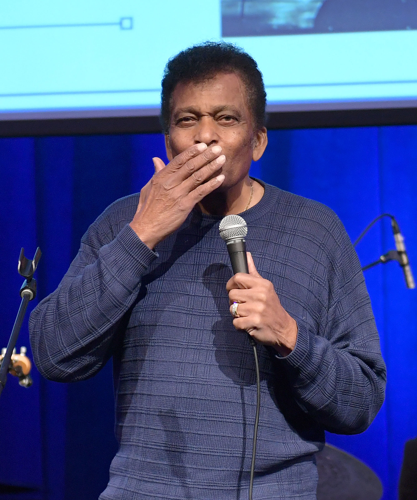

Charley Frank Pride was a rare commodity. Not only was he an icon with universal appeal, but his six-decade career also embodied a strong message that many to this day still don't understand. He was living proof that being true to yourself and what you love is the highest form of cultural authenticity, and that country music — as much as music of any other tradition — belongs to everyone. Pride, who died Dec. 12 at 86 of complications from COVID-19, was the first Black superstar in country music's modern era, although he knew better than most that he wasn't the idiom's first African American performer.

As he rose to unprecedented heights, Pride overcame hostility and treatment that would have crushed a less resilient person. Instead, he persevered, offering fans a combination of a splendid, resonant baritone, naturally charismatic stage presence and remarkably savvy song selection. His brand of just-plain-folks humility and ease in any setting enabled him to win over even the most skeptical sort regarding whether he was truly “country.”

In fact, Pride was about as country as it gets, the son of a sharecropper who picked cotton as a child. One of the myths he obliterated during one of my interviews with him was something I heard quite a bit in the late ’60s and early ’70s: that he'd adopted country music because he wasn't familiar with blues, soul or gospel. That kind of idiocy seems in retrospect to be profoundly absurd regarding someone who grew up in Sledge, Miss., but there were folks who believed it with a degree of passion often reserved for arguing that the Earth is flat.

"I never said I didn't hear that music,” Pride once told me. “I love all kinds of music. But country is what really captivated me. It was what I loved and wanted to sing.” It was just that simple for him. Born into a family of 11 children, Pride had help from his mother Tessie in purchasing his first guitar, a $10 number out of a Sears Roebuck catalog. He schooled himself with the Grand Ole Opry, paying special attention to The Louvin Brothers. He related another formative experience in his 1994 autobiography Pride: The Charley Pride Story — his first country concert, performed by DJ and singer Smilin' Eddie Hill on a flatbed truck.

But for a time it seemed that baseball, not music, would be Pride’s ticket out of the Delta. He chased the Major League dream in the ’50s, not only playing in the Negro Leagues but also MLB's minors, pitching for teams in multiple states. His best year was 1956, when he was on the Negro American League all-star team. But he also got drafted that year, and served in the military until 1958.

In Pride, the singer acknowledges that his plan was to play baseball into his mid-30s and then give music a shot. But his fastball lost some zip, and by 1962 he was living in Helena, Mont., dividing his time between semipro ball, working as a smelter and occasionally singing in local bars. Then his life changed forever when he appeared on a gig in Helena with Red Sovine and Red Foley. Impressed by Pride’s renditions of “Lovesick Blues” and “Heartaches by the Number,” Sovine encouraged him to visit Nashville. The next year, Pride did stop in Music City and met Jack D. Johnson, who’d become his manager. In 1965, Pride recorded with visionary producer Cowboy Jack Clement, and the results led Chet Atkins to sign Pride to his first record deal with RCA.

Pride was among the most incurable optimists you'll ever meet and someone with remarkably little bitterness, no matter how justified bitterness might have been. As his stature rose and his fame was cemented, he'd only discuss indignities during interviews if pushed, though his autobiography certainly details plenty of them. His early singles, particularly gems like “The Snakes Crawl at Night,” were successful as radio hits without RCA having to inform audiences a Black man was singing them.

But in concert, when folks saw exactly who was performing, things could get ugly. He often pointed to a landmark 1966 Detroit performance where he’d experience his biggest audience yet realizing for the first time that he was Black. As Pride told The Tennessean in November, Clement helped him come up with an approach to cut the tension: “ ‘Ladies and gentlemen, I realize it's a little unique with me comin’ out onstage wearin’ this permanent tan. I got three singles — I only have 10 minutes — I get through with those, I'll maybe do a Hank Williams song, but I ain't got time to talk about pigmentation.’ And I hit it.”

From 1967 on through the ’70s and into the ’80s, Charley Pride was a commercial hurricane. He'd ultimately have 29 songs reach No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart, with more than 50 in the top 10, and he became RCA's best-selling artist since Elvis Presley. He also was a voice and inspiration for other Blacks, both those who were simply fans and those who wanted to be performers. These were people who grew up not just appreciating but immersing themselves in country. Their love of the music was no sign of disdain for their background or heritage — just what they preferred to perform or listen to.

Pride ascended to legendary status in the ’70s, winning honors no Black artist ever had in country music. The Country Music Association named him Entertainer of the Year and Male Vocalist of the Year in 1971. In 1972, he was the CMA’s Male Vocalist of the Year again, making him the first artist ever to take home back-to-back trophies in the category — a category in which he had competition like Merle Haggard and Conway Twitty. Over the course of his career, Pride also won three Grammys in member-voted categories as well as the Recording Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award. Long after the hits ended, his impact and fan base endured. He joined the Grand Ole Opry in 1993 and entered the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2000.

Pride’s death came a month after his appearance at the CMA Awards. Though it’s been noted that many in the studio audience appeared unmasked, the CMA and Pride’s representatives released a joint statement indicating he’d tested negative for the coronavirus before, during and after the ceremony.

During the show, Pride was recognized with the Willie Nelson Lifetime Achievement Award. Jimmie Allen, a rising Black country star who treasures and reveres Pride, joined him onstage to sing one of his anthems, “Kiss an Angel Good Morning.” I spoke with Allen for The Tennessee Tribune before he headlined his first Ryman show on Dec. 17, and he related what it meant to sing alongside his idol.

“Charley Pride was a great man and a great artist who showed us that no matter what you look like, or where you come from, there are no limitations on what you can do in country music,” Allen said. “His life and career is a direct reflection that country music is for everyone.”

Tributes to Pride have come from a host of country stars. Among the most poignant was Marty Stuart telling Rolling Stone about the first time he heard Charley Pride.

“He’s from Sledge, Mississippi, I’m from Philadelphia, Mississippi,” Stuart said. “So when I was a little boy, he was one of those heroes — like one of our guys that made it. … There was a country music disc jockey named Marty Collins. He played a Charley Pride song called ‘All I Have to Offer You Is Me.’ He announced it as Charley Pride’s new release. When the record was over, Marty Collins came back on the air, and you could tell he had been crying. And he said, ‘I believe I need to hear that one more time.’ And he played it again. And I stood there kind of frozen in front of the stereo, kind of mesmerized by the sound of his voice and that recording and the song. He just had it all.”

In recent years, widespread viewing of Ken Burns' Country helped set the record straight regarding Black artists’ crucial role in country's evolution. In addition to male stars like Jimmie Allen, Darius Rucker and Kane Brown, there’s also been an impressive wave of Black women country and roots vocalists coming to the fore, like Mickey Guyton, Rhiannon Giddens, Miko Marks, Yola, Valerie June and Rissi Palmer. Palmer’s Apple Music Radio show Color Me Country is turning heads worldwide, and she recently joined up with Kelly McCartney to establish the Color Me Country Fund to help Black and indigenous people and other people of color get established in country music. Charley Pride's legacy is in great hands, and is being rightly celebrated and expanded. He was irreplaceable, and will truly be missed.