Country music offers a perfect vantage point to view the ongoing racial reckoning America began in 2020. Racist policies and attitudes are a big problem in country music, and this throws into relief long-standing racial inequity across our nation. But there are also lessons to be learned from a space that we’re not really looking at: bro country. Despite being caught on film using the N-word, Morgan Wallen is still country music’s statistical leading star. However, an artist who is Wallen’s Black or multiracial analog, like Jimmie Allen or Kane Brown, could eclipse his prodigious fan base.

Yes, bro country is a realm reserved for tall, handsome, square-jawed dudes bearing “aw shucks” grins and a love of hip-hop and hard rock. Their personas are about driving pickup trucks, drinking doubles and/or sleeping around — while still making time for the Lord on Sunday and occasionally showing a sensitive side. Despite portraying arguably the most groan-worthy stereotypes in music, this collection of artists is playing an increasingly large part in country music’s mainstream.

At present, Black female vocalist (and bro antithesis) Mickey Guyton seems to be the one woman benefiting from any movement toward better treatment of Black country artists. She received a Grammy nomination for Best Country Solo Performance for her influential racial-equity anthem “Black Like Me” and performed the song live on the broadcast. Plus, she is hosting the Academy of Country Music Awards alongside Keith Urban in April and — after more than a decade of mainstream experience — is nominated for Best New Artist.

Though Guyton is finally getting some of the recognition due her, new information makes it absolutely plain that the country music industry doesn’t currently give Black artists the same support it offers their white counterparts. Canadian researcher Dr. Jada Watson has recently published survey data from the past 20 years of mainstream country music, highlighting that artists of color received a meager 2.3 percent of country music’s all-important radio spins over the past 19 years. Moreover, as it relates to Mickey Guyton’s emerging stardom, more than 95 percent of that small sliver of airplay went to men of color primarily identified as country artists, while only 2.7 percent went to WOC country artists; the rest is made up of artists of color crossing over from other genres who appeared on country radio.

“Country is the last genre that’s still heavily reliant on radio, so that plays a big role,” says William Bruce West, a longtime culture writer and country music fan who is also a Black man. “I think race will continue to be a factor because a lot of country programmers aren’t willing to take risks. Instead of doing ‘blind musical taste tests’ of sorts, they’ll just continue to promote what everyone already loves. Until that changes, country will remain a white bro’s game.”

It’s unquestionable that artists like Guyton — and an emerging crew of other BIPOC women — deserve to be at the forefront of the movement for racial equity in country. But it’s also useful to consider the genre’s “strong Black male leads,” to borrow some Hollywood terminology, who are already making some notable inroads.

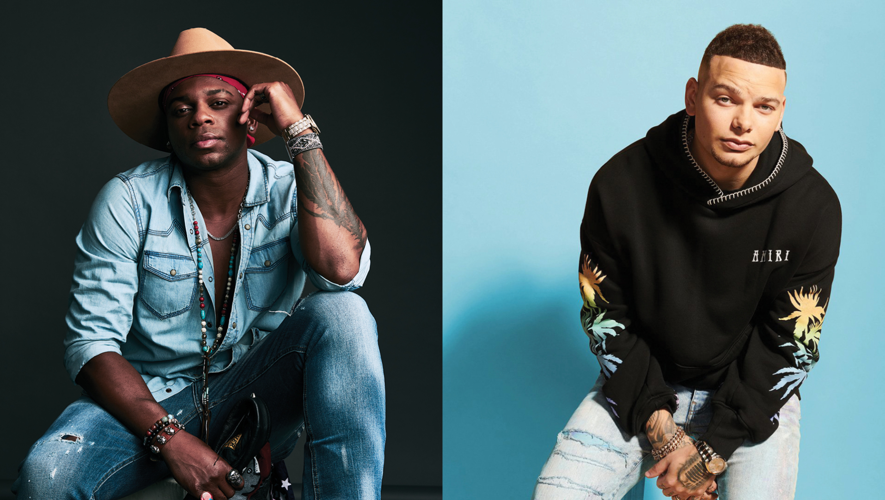

Jimmie Allen

Setting aside Lil Nas X’s historic 2019 chart run with “Old Town Road,” we can look at Blanco Brown’s “The Git Up,” which went to No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart and broke the top 20 of the all-genre Hot 100 chart. Breland’s “My Truck” was certified gold in August and hit No. 26 on Hot Country Songs. Jimmie Allen, who made his Ryman headlining debut in December, scored two No. 1 singles on Billboard’s U.S. Country Airplay chart with 2018’s “Best Shot” and 2019’s “Make Me Want To.”

Willie Jones, who signed earlier this month with Sony Music Nashville, directly confronts racism and its multigenerational impacts in his single “American Dream.” A savvy businessperson, Jones spoke to Billboard about his appreciation for the weight he sees the label putting behind artists like Kane Brown. Brown, a multiracial Georgia native, is building on historic chart success — he was the first artist ever to top all five of Billboard’s country charts at the same time in 2017, and his 2018 LP Experiment has gone platinum — with some significant sources of power and potential income streams. He’s launched his own publishing company called Verse 2 and an artist-development-focused label called 1021 Entertainment in joint ventures with Sony.

As Black bro country refines itself, it’s also poised for a potential pop crossover in cities across America. Brittany Vance, a writer and passionate country music fan, lives about an hour outside of Washington, D.C., in Frederick, Md. She’s a white West Virginia native with a 10-year-old son who is biracial and on the autism spectrum. She’s an ideal person with whom to discuss the impact of Black male representation on country music.

Vance’s son is particularly fond of Jimmie Allen, though he’s also seen Kane Brown live and has a Willie Jones T-shirt. Vance notes that a significant part of Allen’s success can be attributed to the fact that he’s “a country traditionalist,” whose “lyrics and looks are very similar to a lot of country music’s most famous white artists.” She adds a poignant parental note about how important it is for her son to see Black artists onstage and online as a more significant part of the vanguard of country music’s future.

Kane Brown

“Representation matters,” Vance says. “My son looks up to artists like Jimmie Allen, Kane Brown and Willie Jones. For a kid with developmental disabilities, music is powerful. Because he’s autistic, he learns better by sight than by words. If he saw nothing but white country artists, he would automatically [think] that Black people don’t sing country music.”

The increasing success of Black artists in bro country doesn’t diminish or in any way make up for the racist hate faced by Black and brown country artists, past or present. But the numbers don’t lie: Where there are hits, there’s money being made. And when Black artists get support from labels, they have big hits. Right now, Black country bros are getting that support, and they’re working their way into the fabric of American popular culture. Imagine what an impact it would have if that support were extended to a broader range of BIPOC artists.